As the world commemorates the 35th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol, it’s worth taking a moment to appreciate this landmark agreement’s monumental impact on our planet. Officially known as the “Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer,” this treaty stands as one of the most successful environmental accords in history, showcasing what humanity can achieve when it comes together to solve a global crisis. In this blog post, I invite you to explore the science behind the ozone layer, the devastating effects of its depletion, and how the Montreal Protocol has not only reversed these trends but also contributed significantly to climate protection.

Understanding the Ozone Layer:

Before exploring the Montreal Protocol’s achievements, it’s essential to understand what the ozone layer is and why it’s so vital for life on Earth.

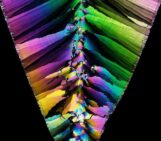

The ozone layer is a region of the Earth’s stratosphere, located about 7 to 25 miles above the surface, and contains a high concentration of ozone (O₃) molecules. This layer plays a crucial role in shielding the planet from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, particularly UV-B rays. Without this protective shield, life on Earth would be exposed to dangerous levels of radiation which could lead to severe health consequences, including an increase in skin cancers, cataracts, and immune system suppression. Excessive UV radiation can also harm marine ecosystems, reduce crop yields, and disrupt the delicate balance of our planet’s biosphere.

However, in the mid-20th century, human activities began to threaten this crucial layer of the atmosphere.

How CFCs were destroying the Ozone layer

In the 1970s, scientists, including many from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), made a shocking discovery: Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—chemicals widely used in refrigeration, air conditioning, foam production, and aerosol propellants—were causing significant damage to the ozone layer. These chemicals, once released into the atmosphere, would rise into the stratosphere, where they were broken down by UV radiation, and would release chlorine and bromine atoms. These atoms, in turn, initiated chemical reactions that led to the destruction of ozone molecules.

The most alarming consequence of this process was the formation of a massive “hole” in the ozone layer over Antarctica, which was observed to be growing larger each year. This depletion allowed more UV-B radiation to reach the Earth’s surface, which increased the risk of health problems and environmental damage. The scientific community raised the alarm and called for immediate global action to address this impending catastrophe.

The Montreal Protocol: A model of international cooperation

In response to these dire warnings, world leaders came together to negotiate what would become the Montreal Protocol. Adopted in 1987 and entering into force in 1989, the protocol was designed to phase out the production and use of ozone-depleting substances (ODS), including CFCs, halons, and other related chemicals. The treaty was ground-breaking not just for its environmental focus but also for its universal support—197 U.N. member states ratified it, making it the first U.N. treaty to achieve universal ratification.

President Ronald Reagan, who signed the treaty on behalf of the United States, hailed it as a “model of cooperation,” emphasizing the importance of scientific research in guiding global policy decisions. Over the years, the protocol has been amended multiple times to address emerging challenges and incorporate new scientific findings. These amendments have helped the treaty remain effective in protecting the ozone layer while also addressing broader environmental issues, such as climate change.

Healing the ozone layer and beyond:

The Montreal Protocol’s success is evident in the significant reduction of ozone-depleting substances in the atmosphere. Thanks to the treaty, global production and use of CFCs and other harmful chemicals have been reduced by more than 99%. As a result, the ozone layer is on the path to recovery, with scientists predicting it could return to pre-1980 levels by the middle of the 21st century.

But the protocol’s impact extends far beyond just ozone protection. CFCs and other ODS are also potent greenhouse gases, meaning their reduction has contributed significantly to the fight against climate change. By phasing out these substances, the Montreal Protocol has helped prevent an estimated 135 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions, making it one of the most effective climate treaties ever implemented.

The unintended consequences:

While the Montreal Protocol has been remarkably successful, it has also faced challenges, particularly concerning the substitutes developed to replace CFCs. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), initially introduced as a safer alternative, do not deplete the ozone layer but are powerful greenhouse gases with a global warming potential thousands of times greater than carbon dioxide.

Recognizing this new threat, the international community adopted the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol in 2016. This amendment, which came into force in 2019, aims to phase down the global production and consumption of HFCs, thereby preventing up to 0.5 degrees Celsius of global warming by the end of the century. The Kigali Amendment represents a significant step forward in aligning ozone protection with climate action and showcases the protocol’s adaptability and continued relevance in addressing environmental challenges.

The future of Ozone protection:

As we celebrate 35 years of the Montreal Protocol, it’s clear that the work is far from over. The treaty will continue to play a critical role in protecting the ozone layer and mitigating climate change, but new challenges are on the horizon.

One emerging concern is the potential impact of increased space traffic on the ozone layer. As the number of rocket launches grows, so does the risk of emissions of soot and other particles into the stratosphere, which could deplete ozone in certain regions and seasons. Researchers at NOAA and other institutions are actively studying these effects to better understand the potential risks and develop strategies to mitigate them.

Another challenge is the aging of satellites and other instruments that monitor ozone levels and atmospheric conditions. Many of these satellites are due to be retired within the next few years, raising concerns about our ability to track changes in the ozone layer and respond to new threats. Ensuring that we have the necessary tools to continue monitoring and protecting the ozone layer will be crucial in the years ahead.

Lessons from the Montreal Protocol:

The success of the Montreal Protocol offers valuable lessons for addressing other global environmental challenges, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. Among these lessons is the importance of science in guiding policy decisions. The protocol was based on scientific research, and its success has been driven by the ongoing collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and industry leaders.

Another critical factor has been the international cooperation that underpinned the treaty. The Montreal Protocol brought together countries with diverse interests and levels of development and successfully united them in a common cause. This cooperation was facilitated by the treaty’s flexible design, which allowed for periodic updates and adjustments based on new scientific findings and technological advancements.

The Montreal Protocol demonstrates the power of proactive, preventive action. Thanks to the collaborative efforts in addressing the ozone depletion crisis before it reached a tipping point, the treaty avoided potentially catastrophic consequences for human health and life on our planet. This proactive approach can and should be applied to other pressing global issues to ensure that we act in time to protect our planet for future generations.