The Cryptoblepharus egeriae, more commonly known as the Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skink, once inhabited Christmas Island. The Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skink was discovered in 1886.[3] In 2002 scientists with the Christmas Island National Parks discovered that the yellow crazy ant (Anoplolepis gracilipes) was becoming a threat to the Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skink.[4] Since their introduction in 1980 the yellow crazy ants had started to massively disrupt the biodiversity on Christmas Island.[4] This discovery put the Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skink on the endangered animals list in 2006.[5] By 2009 Taronga Zoo decided to start an active breeding program in hopes of being able to release some of the skinks back into the wild.[6] However, by 2010 the Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skink was extinct in the wild.

| Christmas Island blue-tailed shining-skink | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1900 monograph of three Christmas Island reptiles, with the Christmas Island blue-tailed shinning-skink at right. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Cryptoblepharus |

| Species: | C. egeriae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cryptoblepharus egeriae (Boulenger, 1888)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Etymology

The specific name, egeriae, is in honor of HMS Egeria.[7]

Description

The Christmas island blue-tailed skink typically grows to be 4-5cm in length.[5] It can be identified by its small black body with two yellow strips running vertically down the skink's back and into its vibrant blue tail. The skink can use its blue tail to draw a predator’s attention away from its body by separating its tail from its body. The bright colour of the skink's tail means predators are much more likely to notice the tail than the skink's black body.[3]

Diet

The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink is a forager known as an insectivore.[5] Their diet primarily consists of crickets, beetles, flies, grasshoppers, spiders, and earthworms. They will occasionally eat some vegetation, though insects remain their primary source of food. Because of its small size the blue-tailed skink forages for its food on the ground, over exposed rocks and low-laying vegetation, and will generally only eat prey that are slower moving.[7]

Reproduction

For the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink, their first breeding season occurs when they are approximately one year old.[7] The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink typically lives for seven years in the wild, six of which are active breeding years. The male Christmas Island blue-tailed skink will demonstrate courtship behaviour when trying to find a mate. The female Christmas Island blue-tailed skink will emit biochemicals for the males to smell, letting them know that the female is in her fertile stage of reproduction.[3] Male Christmas Island blue-tailed skinks will often fight each other to win a female mate during breeding season. These skinks are polygamous which increases their chance of having offspring. Once the female Christmas Island blue-tailed skink has been fertilized, they are oviparous and will generally lay two eggs at a time, with a 75-day incubation period.[7]

Distribution

The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink is endemic to Christmas Island.[8] Until the late 1990s, the blue-tailed skink could be found over the whole of Christmas Island. The species' distribution became more sparse once the yellow crazy ant was introduced to the island, leading to a decline in the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink's population.[3]

In 2009 Taronga Conservation Society began conservation efforts to save the skink. This led to 300 of the Christmas Island Blue-Tailed Skinks being introduced to a small island called Pulu Blan in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. [9]

Conservation Efforts

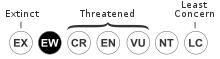

The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink is now extinct in the wild. However, Taronga Zoo currently has an active breeding program hosted by Taronga Conservation Society, in hopes of being able to release some of the skinks back into their native habitat.[6] The breeding program has been running for over a decade. Since the Taronga Conservation Society conservation efforts began 150 Christmas Island blue-tailed skinks have been released back onto Christmas Island and 300 skinks were transported to Pulu Blan.[6] These skinks were successfully bred in captivity by Taronga Conservation after Christmas Island national parks rangers were able to successfully save 66 skinks before their population was wiped out.[6]

The threat of extinction is largely attributed to the yellow crazy ants that were unintentionally brought to Christmas Island in 1980.[4] Yellow crazy ants had a large growth in their population which coincided with the decline of the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink as well as the decline of much of the biodiversity on Christmas Island.[4]

Evolutionary relationships

C. egeriae is most closely related to the metallicus group of Cryptoblepharus, native to Australia, with the estimated divergence of C. egeriae from the group taking place around 7 million years ago,[8]

See also

References

- ^ Woinarski, J.C.Z.; Cogger, H.; Mitchell, N.M.; Emery, J. (2017). "Cryptoblepharus egeriae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T102327291A102327566. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T102327291A102327566.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Cryptoblepharus egeriae ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ a b c d Boulenger, G. A. (20 August 2009). "On the Reptiles of Christmas Island". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 56 (1): 534–536. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1888.tb06729.x. ISSN 0370-2774.

- ^ a b c d "Yellow crazy ant biocontrol". parksaustralia.gov.au. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Options beyond captivity for two critically endangered Christmas Island reptiles". www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Saving the Blue-Tailed Skink". Saving the Blue-Tailed Skink | Taronga Conservation Society Australia. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Cryptoblepharus egeriae, p. 81).

- ^ a b Oliver, Paul M.; Blom, Mozes P. K.; Cogger, Harold G.; Fisher, Robert N.; Richmond, Jonathan Q.; Woinarski, John C. Z. (30 June 2018). "Insular biogeographic origins and high phylogenetic distinctiveness for a recently depleted lizard fauna from Christmas Island, Australia". Biology Letters. 14 (6): 20170696. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0696. PMC 6030605. PMID 29899126.

- ^ "Saving the Blue-Tailed Skink". Saving the Blue-Tailed Skink | Taronga Conservation Society Australia. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

Further reading

- Boulenger GA (1888). "On the Reptiles of Christmas Island". Proc. Zool Soc. London 1888: 534–536. ("Ablepharus egeriæ ", new species, pp. 535–536).

External links