Juan Sebastián Elcano: Difference between revisions

→500th anniversary: repeated picture |

Navarran94 (talk | contribs) Adding official source of the Real Academia de la Historia. Not deleting anything, but adding data and an official source. Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| signature = [[File:Firma Elcano.svg|155px|]] |

| signature = [[File:Firma Elcano.svg|155px|]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Juan Sebastián Elcano'''<ref name="riev">{{Cite journal |last=Múgica Zufiría |first=Serapio |date=1920 |title=Elcano y no Cano |trans-title=Elcano and not Cano |url=https://www.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/publicaciones/elcano-y-no-cano/art-11908/ |journal=Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos |language=es |volume=11 |pages=194–213}}</ref> ('''Elkano''' in modern [[Basque language|Basque]]<ref>{{Cite web |last=Euskaltzandia |first= |date=2021 |title='Juan Sebastian Elkano' idaztea hobetsi du Euskaltzaindiko Onomastika Batzordeak |url=https://www.euskaltzaindia.eus/euskaltzaindia/komunikazioa/plazaberri/6249-juan-sebastian-elkano-idaztea-hobetsi-du-euskaltzaindiko-onomastika-batzordeak |access-date=2022-09-07 |website=www.euskaltzaindia.eus |language=eu-es}}</ref>; sometimes misspelled ''del Cano'';<ref name=riev/> 1486/1487<ref name="personal-archive">{{Cite journal |last=Aguinagalde |first=F. Borja |date=2018 |title=El archivo personal de Juan Sebastián de Elcano (1487-1526), Marino de Getaria |url=https://www.inmedioorbe.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/TEXTO-6-EL-ARCHIVO-PERSONAL-DE-JUAN-SEBASTIAN-DE-ELCANO.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=IMO. In Medio Orbe 1519-1522 |language=es |issn=2659-3556 |number=1}}</ref><ref group="n">Some sources state that he was born on 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean when we was a child. According to his own answer of the age he had when he boarded the expedition, he was born 10 years later, around 1486 or 1487.</ref> – 4 August 1526) was a [[Basques|Basque]]{{#tag:ref|Elcano was Basque, as was noted also by other members of the expedition. [[Martín de Ayamonte]], in his relation to the Portuguese inquity, clearly said that the captain was [[Biscayne_(ethnonym)|Biscayne]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Testimonio de Martín de Ayamonte|url=https://en.rutaelcano.com/martin-ayamonte |access-date=2022-09-07 |website=primeravueltalmundo |language=es}}</ref><ref name=":7" />. Modern sources also state this<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-09-01 |title=Juan Sebastián Elcano, el vasco que dio la vuelta a la historia |url=https://www.elcorreo.com/tiempo-de-historias/elcano-20220906173142-nt.html |access-date=2022-09-08 |website=El Correo |language=es}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-08-31 |title=Magellan got the credit, but this man was first to sail around the world |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/this-man-was-actually-first-to-sail-around-the-world |access-date=2022-09-08 |website=History |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Woodworth |first=Paddy |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/727949806 |title=The Basque Country : a Cultural History |date=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-804394-2 |location=Oxford |oclc=727949806}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Juan Sebastián del Cano {{!}} Spanish navigator {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Sebastian-del-Cano |access-date=2022-09-15 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Zulaika|first=D.|year=2019|title=Elcano, los vascos y la primera vuelta al mundo|url=https://www.kutxakultur.eus/wp-content/uploads/ELCANO-LOS-VASCOS-Y-LA-PRIMERA.-Definitiva-19-julio-2019.pdf|language=es|publisher=Kutxa Kultur}}</ref>.|group="n"}} |

'''Juan Sebastián Elcano'''<ref name="riev">{{Cite journal |last=Múgica Zufiría |first=Serapio |date=1920 |title=Elcano y no Cano |trans-title=Elcano and not Cano |url=https://www.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/publicaciones/elcano-y-no-cano/art-11908/ |journal=Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos |language=es |volume=11 |pages=194–213}}</ref> ('''Elkano''' in modern [[Basque language|Basque]]<ref>{{Cite web |last=Euskaltzandia |first= |date=2021 |title='Juan Sebastian Elkano' idaztea hobetsi du Euskaltzaindiko Onomastika Batzordeak |url=https://www.euskaltzaindia.eus/euskaltzaindia/komunikazioa/plazaberri/6249-juan-sebastian-elkano-idaztea-hobetsi-du-euskaltzaindiko-onomastika-batzordeak |access-date=2022-09-07 |website=www.euskaltzaindia.eus |language=eu-es}}</ref>; sometimes misspelled ''del Cano'';<ref name=riev/> 1486/1487<ref name="personal-archive">{{Cite journal |last=Aguinagalde |first=F. Borja |date=2018 |title=El archivo personal de Juan Sebastián de Elcano (1487-1526), Marino de Getaria |url=https://www.inmedioorbe.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/TEXTO-6-EL-ARCHIVO-PERSONAL-DE-JUAN-SEBASTIAN-DE-ELCANO.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=IMO. In Medio Orbe 1519-1522 |language=es |issn=2659-3556 |number=1}}</ref><ref group="n">Some sources state that he was born on 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean when we was a child. According to his own answer of the age he had when he boarded the expedition, he was born 10 years later, around 1486 or 1487.</ref> – 4 August 1526) was a [[Spaniards|Spanish]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Juan Sebastián Elcano. Biografía|url=https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/6481/juan-sebastian-elcano |access-date=2022-09-15 |website=[[Real Academia de la Historia]]|language=es}}</ref> navigator, ship-owner and explorer of [[Basques|Basque]] origin{{#tag:ref|Elcano was Basque, as was noted also by other members of the expedition. [[Martín de Ayamonte]], in his relation to the Portuguese inquity, clearly said that the captain was [[Biscayne_(ethnonym)|Biscayne]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Testimonio de Martín de Ayamonte|url=https://en.rutaelcano.com/martin-ayamonte |access-date=2022-09-07 |website=primeravueltalmundo |language=es}}</ref><ref name=":7" />. Modern sources also state this<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-09-01 |title=Juan Sebastián Elcano, el vasco que dio la vuelta a la historia |url=https://www.elcorreo.com/tiempo-de-historias/elcano-20220906173142-nt.html |access-date=2022-09-08 |website=El Correo |language=es}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-08-31 |title=Magellan got the credit, but this man was first to sail around the world |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/this-man-was-actually-first-to-sail-around-the-world |access-date=2022-09-08 |website=History |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Woodworth |first=Paddy |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/727949806 |title=The Basque Country : a Cultural History |date=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-804394-2 |location=Oxford |oclc=727949806}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Juan Sebastián del Cano {{!}} Spanish navigator {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Sebastian-del-Cano |access-date=2022-09-15 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Zulaika|first=D.|year=2019|title=Elcano, los vascos y la primera vuelta al mundo|url=https://www.kutxakultur.eus/wp-content/uploads/ELCANO-LOS-VASCOS-Y-LA-PRIMERA.-Definitiva-19-julio-2019.pdf|language=es|publisher=Kutxa Kultur}}</ref>.|group="n"}} from [[Getaria (Spain)|Getaria]], currently in [[Spain]] and part of the [[Crown of Castile]] when he was born, best known for having completed the first [[circumnavigation]] of the Earth in the ship ''[[Victoria (ship)|Victoria]]'' on the [[Magellan expedition]] to the [[Spice Islands]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Totoricagüena |first=Gloria Pilar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xy6p3D4AoTIC |title=Basque Diaspora: Migration And Transnational Identity |date=2005 |publisher=[[University of Nevada Press]] |isbn=9781877802454 |page=132 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="FacarosPauls2008">{{Cite book |last1=Facaros |first1=Dana |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dz3ZvAEACAAJ |title=Bilbao & the Basque Lands |last2=Pauls |first2=Michael |date=2008 |publisher=Cadogan Guide |isbn=978-1-86011-400-7 |page=177 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Salmoral1982">{{Cite book |last=Salmoral |first=Manuel Lucena |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4DWBNjs8iwEC |title=Historia general de España y América: hasta fines del siglo XVI. El descubrimiento y la fundación de los reinos ultramarinos |publisher=Ediciones Rialp |year=1982 |isbn=978-84-321-2102-9 |page=324 |language=es |access-date=7 January 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131013101510/https://books.google.com/books?id=4DWBNjs8iwEC |archive-date=2013-10-13 |url-status=dead}}</ref> He received recognition for his achievement by the Emperor Charles V with the coat of arms reading "''primus circumdedisti me''". |

||

Although it is known that Elcano circumnavigated the world, data on Elcano are scarce. Elcano is the subject of great [[Historiography|historiographical]] controversy due to the scarcity of original sources to know his life and thought.<ref name=":7" /> For example, in Spain the first biographies about him began to be written in the second half of the 19th century, after three centuries of emptiness. |

Although it is known that Elcano circumnavigated the world, data on Elcano are scarce. Elcano is the subject of great [[Historiography|historiographical]] controversy due to the scarcity of original sources to know his life and thought.<ref name=":7" /> For example, in Spain the first biographies about him began to be written in the second half of the 19th century, after three centuries of emptiness. |

||

Revision as of 19:31, 15 September 2022

Juan Sebastián Elcano | |

|---|---|

Modern engraving of Elcano | |

| Born | Juan Sebastián Elcano c. 1486 |

| Died | August 4, 1526 (aged 39–40) |

| Occupation(s) | Explorer, navigator, mariner and military |

| Known for | First circumnavigation of the Earth |

| Partner | María Hernández Dernialde |

| Children | N. Elcano (daughter) and Domingo Elcano (son). |

| Parent(s) | Domingo Sebastián Elcano I, and Catalina del Puerto |

| Signature | |

| |

Juan Sebastián Elcano[1] (Elkano in modern Basque[2]; sometimes misspelled del Cano;[1] 1486/1487[3][n 1] – 4 August 1526) was a Spanish[4] navigator, ship-owner and explorer of Basque origin[n 2] from Getaria, currently in Spain and part of the Crown of Castile when he was born, best known for having completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth in the ship Victoria on the Magellan expedition to the Spice Islands.[12][13][14] He received recognition for his achievement by the Emperor Charles V with the coat of arms reading "primus circumdedisti me".

Although it is known that Elcano circumnavigated the world, data on Elcano are scarce. Elcano is the subject of great historiographical controversy due to the scarcity of original sources to know his life and thought.[6] For example, in Spain the first biographies about him began to be written in the second half of the 19th century, after three centuries of emptiness.

Following his success, the emperor entrusted him with another large expedition to the Spice Islands headed by a nobleman, García Jofre de Loaisa, which could not complete its goal. Elcano died in the Pacific Ocean during this venture.

Name

Elcano's name has been written in different ways throughout historiography. Although today in Basque Elkano is used, his signature seems to be Delcano, or possibly Del Cano, although it is difficult to detect. Santamaría shows that his lack of expertise when signing make him create gaps between letters, so sometimes he signed "del ca no".[6] The most common in Spanish historiography has been to interpret it as Del Cano (de Cano), but also as Cano.

However, near Getaria (today between Zarautz and Aia) is the neighborhood of Elkano, whose family or lineage was known as Elkano or Elcano, so it could be said that it belongs to the Elkano family. For this reason, later, Elcano has been used as a surname in Spanish and Elkano in Basque, to indicate that it was from Elcano (from the Elkano lineage).

Mitxelena, in his book Apellidos vascos,[15] interprets the surname Elkano from Basque. Between the suffixes -ano and -no, he provides arguments for the latter, for the diminutive suffix. He proposes that the first part of the surname is elge.[16][17] Mitxelena reconstructs the previous form of this elge, and argues that the surname Elkano is a toponym and a surname arising from the association of these two morphemes. It exists in different spots of the Basque Country as a minor place name, but also as a village.

Family

Juan Sebastián Elcano's mother was Catalina del Puerto or Catalina Portu, his father Domingo Sebastián Elcano. It is known that Catalina, Elcano's mother, was alive at the death of Elcano, whose will she had requested upon her arrival in Getaria (10 years after Elcano's death) what was legally due to her. For example, she asked the king for the pension that had been promised to Elcano. Elcano's grandmother, Catalina's mother is also known: Domenja Olazabal. Originally it is believed that she belongs to a family of noblemen from the area of Tolosa.[3] It is also known that this maternal family, that of the Portu or Puerto, was closely linked to the church and the secretaries.[18]

Catalina had eight children, and Elcano would be the fourth. Her first son was born in 1481. Later their daughter Catalina would be born, who would marry Rodrigo de Gainza and have a son. Next came Domingo Elcano. This one took the name of his father and would be a priest in Getaria. Juan Sebastian was the fourth brother. And after him four other brothers: Martín Pérez, Otxoa Martínez, Inés and Antton Martínez.[19] As these last three (Martín Pérez, Antón Martínez and Otxoa Martínez) were also sailors, they would set sail with Elcano in the second expedition to the Moluccas. It seems that Elcano also had a half-sister, María, Domingo's illegitimate daughter.[20]

Elcano left two children. He had a son with Mari Hernández de Hernialde, Domingo Elcano, in Getaria. He had another daughter with a woman called Maria Bidaurreta, called also Maria (Elcano), born in Valladolid.[21] In the will, he bequeathed 100 ducats to the mother of his son, María Hernández de Hernialde. To the daughter he had with María Bidaurreta he promised again 40 ducats, but conditioned that quantity on their offspring coming to live in Getaria before she was 4 years old.[22]

Family social position and economic status

It is believed that, economically, the Elcano formed a family of maritime transporters-traders. They may have been already trading in the Mediterranean.[23] The ownership of a vessel can almost be taken for granted by the amount of taxes paid by the family in 1500.[24]

However, everything has been said about the family property. Some sources say they were from noble families, others say they were poor. In the 19th century, for example, it was said that the Elcano family was a noble family. But this is a questionable statement. Elcano asked the king for the right to bear arms, a right proper to nobles, and his brothers accompanied him on the next expedition.[25] So the Elcanos, on their father's side, at least, were neither nobles nor hidalgos, and the Portus were probably not nobles either, on their mother's side. However, the Olazabal family on the grandmother's side may have been hidalgos, but since nobility was not inherited through women, the Portus (Catalina, daughter of Domenja) would not be hidalgos and much less the Elcanos (grandchildren of Domenja).

Fernandez de Navarrete states that, in addition to being a fisherman and sailor, Elcano acted as a smuggler on board with France,[26] but no original sources are given to confirm this.[20] On the other hand, some biographies to the contrary point out that the Elcano family experienced economic hardship because his father died young and his mother had to support eight siblings.[20] However, this assertion on their state of poverty is unfounded.

As attested in documentation, when Elcano was about 14 years old in 1500, there was a large taxation in Getaria in which the father Domingo Elcano appears in the thirteenth position (23 maravedís and a half) of those who paid more money. It seems, then, that they were quite solvent economically, since they are named among the richest families of the town.[25]

In addition, the royal document granting him a pardon states that when Elcano was very young acting as a merchant in the Mediterranean, he was the owner of a large ship. He owned, therefore, a 200-ton vessel. This would also indicate that they had, at least, some economic solvency or debt capacity.

However, Elcano got rich with the round-the-world voyage by earning 613,250 maravedis.[27] It was an immense fortune, an amount equivalent to the salary of a sea pilot for 20 years, as compared to the 23 maravedis paid by his father in municipal taxes. Of that fortune, 104,526 maravedis corresponded to him as a master's and captain's wage, while the rest -most of it- was earned by selling the clove brought in property from the Moluccas.

Biography

Birth

The date of Elcano's birth is unknown. However, it can be inferred with a fair amount of certainty that the year of birth was 1486 or 1487. Spanish historiography on the year of birth has said that he was 42 years old when he sailed with Magallanes, so Elcano was born by 1476.[28] But before setting sail Elcano himself confirmed that he was "approximately" 32 years old, as recorded in the document of August 1519.[29] Therefore, if he was 32 years old in 1519, it is reasonable to think that he was born in 1486 or 1487.[6]

There is not much doubt about his birthplace because in the will written by Elcano himself he mentions that his birthplace is Getaria. It is usually said that he was born in the house located in San Roque Street in the municipality of Getaria, today called the Birthplace of Juan Sebastián Elcano. There is a plaque commemorating the event next to the house where he was born. The house, if so, did not belong to the Elcano family, but to the family of his grandfather (mother's father), the Portu family.[25]

In the chronicles of the time, Elcano is also presented as a "getarian". The chronicler Juan de Mariana, in 1601, after saying that Elcano was from Getaria, adds: "from Biscay by nationality or Guipuscoan".[30] At that time the Basques were called 'vizcaínos'. It has been deduced from indirect data that the Basque language was his mother tongue, but it is unequivocable that he also communicated in Spanish, as can be seen in the interrogations and letters. In addition to Basque and Spanish, it seems that he could read Latin, because the two books referred to in his will were written in that language.

Early life

There is little information about his youth age. That as a young man he owned a large ship and sailed in the Mediterranean, that is certain. Also that he sold the ship to the Savoians and that is why he had legal problems. It is also known that he got the need to sell the ship because the King did not pay him a salary for the 'services rendered'. So he also acted on the King's orders. From there, there are few certainties.

It is often repeated, for example, that in 1509 he participated in the conquest of Oran, in the Mediterranean, under the direction of Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, driving his two hundred ton ship.[31][32][20] However, in the register of ships of the conquest of Oran there is no captain whose name is Elcano (or similar).[33][34][6] According to Spanish historiography, Elcano participated with his ship in the Italian wars under the leadership of Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordova, The Great Captain (1495-1504).[20] But that is also doubtful, because there are no original sources to prove it and, above all, because Elcano was then 8 years old (17 according to the Spanish historiography).[33] It is difficult to think that the boy from 8 to 17 years old was already a ship owner and even more difficult to imagine him in the war.

The King's pardon certificate has been preserved.[3] There it is mentioned that he acted in the service of the King "in the Levant and Africa", but it is not further specified. It also states that since the King did not pay him the promised salaries, he had to sell the ship to the Savoy family. It is, therefore, presumably that when he asked for money from the merchants of Savoy he had to offer them the ship as a guarantee. Therefore, in the case of participating in a military campaign in the Mediterranean 'in the service of the king', perhaps the catastrophe of Gelves (1510) can be considered, since that military defeat would explain Elcano's debt.[34] Forced to pay for the ship and the stern men, but with no war prize, perhaps that is why Elcano got into debt. At the age of twenty-three, with an unpayable debt and on board in Italy, in order to pay the crew, he had to hand over the ship to the Savoyards. The other hypothesis is that Juan Sebastian covered the 'royal services' in the autumn of 1516, during the battle to take Algiers, also a military defeat, and then he had to sell his ship to the Savoyards.[35]

We know that in the summer of 1515 he participated in the local militia. The Royal Corregidor asked 500 Gipuzkoans to go to Hondarribia and San Sebastian to face the threat of the French. And Juan Sebastián went there, along with 11 other compatriots, charging 30 maravedís per day. It seems that, if he had to enroll in the local militia in 1515 and he didn't have a ship then, the idea of taking part in the battle to take Algiers isn't probable.[6] In the 1510s, at the age of twenty-something, it is also surprising to learn that Elcano already owned the great ship of 200 tons. It was unusual for such a young man to take such great care. It is clear that Elcano was a precocious sailor who rose very quickly as a professional. The young Elcano committed a serious legal infraction. Foreigners could not sell ships in times of war because ships were military technology. Since wars were fought with ships, it was illegal to give the ship to the Savoy House. This infringement would cause him numerous problems in the following years.[20]

After returning from the Mediterranean campaign, as he had legal problems, it is likely that he remained in the Mediterranean, in Catalonia or in the Valencia, or perhaps also in Alicante.[20] In fact, in his will he left 24 ducats to the Alicante church of Santa Veronica. However, at the end of June 1517 he appears again in Getaria, since he signed as a witness in the debt letter of a compatriot.[35] Perhaps he also had his son at that time with the young Getarian María Hernández Hernialde, between 1517 and 1518, since they did not marry, probably because Elcano did not have a stable residence.[35] At the end of 1518 Juan Sebastian left Getaria and traveled to Seville to join Magellan's expedition. However, after returning from the expedition, at the age of 35 or 36, the King would forgive him that legal debt, on February 13, 1523, and he was able to stabilize it in Valladolid.

Voyage of circumnavigation

The Magellan-Elcano expedition (1519 - 1522) that completed the circumnavigation started with 5 ships (Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria and Santiago) and 234 members (some sources raise the number of sailors to 247[27]). Although Elcano departed aboard the Concepción, the return voyage from the Moluccas to Seville was made by a single ship, the Victoria, already captained by Elcano.[36] In extreme conditions, only 21 people arrived in Seville, the 18 Europeans 3 Moluccans.

To complete the round-the-world voyage, they had to sail 69,918 km.[37] After three years of rough crossing, most of the sailors died in the way. Some made it back alive later, but 147 sailors lost their lives along the way, 60% of those who set sail from Seville.[38] This figure shows the number of unforeseen events, difficulties and vicissitudes that were encountered during the voyage. 55 of those who returned alive were deserting sailors who had returned from America on the first part of the voyage aboard the San Antonio. They did not circumnavigate the world because they decided to retreat to the Strait of Magellan. Others who returned alive would spend some time in Asia or Cape Verde, although they would later manage to return alive to Europe. And they could have said, once they arrived, that they had sailed around the world. In other words, in addition to the 17 sailors who arrived in Seville along with Elcano, more sailors would sail around the world, albeit later.

In addition to Elcano, the expedition included 34 other Basques, 14% of the expedition,[24] the largest representation after the Andalusians (28 Portuguese, 19 Genoese and 21 Castilians). 9 of the Basques were with Elcano aboard the Concepción. Both Elcano and the Bermeo boatswain Juan de Acurio wanted reliable people around them.[39]

The goal: The Island of the Spices

in southern Chile.

Elcano participated in a fierce mutiny against Ferdinand Magellan before the convoy discovered the passage through South America, the Strait of Magellan. He was spared by Magellan and after five months of hard labour in chains was made captain of the galleon.[40] Santiago was later destroyed in a storm. The fleet sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the eastern coast of Brazil and into Puerto San Julián in Argentina. Several months later they discovered a passage now known as the Strait of Magellan located in the southern tip of South America and sailed through the strait. The crew of San Antonio mutinied and returned to Spain. On 28 November 1520, three ships set sail for the Pacific Ocean and about 19 men died before they reached Guam on 6 March 1521. Conflicts with the nearby island of Rota prevented Magellan and Elcano from resupplying their ships with food and water. They eventually gathered enough supplies and continued their journey to the Philippines and remained there for several weeks. Close relationships developed between the Spaniards and the islanders. They took part in converting the Cebuano tribes to Christianity and became involved in tribal warfare between rival Filipino groups in Mactan Island.

On 27 April 1521, Magellan was killed and the Spaniards defeated by natives in the Battle of Mactan in the Philippines. The surviving members of the expedition could not decide who should succeed Magellan. The men finally voted on a joint command with the leadership divided between Duarte Barbosa and João Serrão. Within four days these two were also dead. They were killed after being betrayed at a feast at the hands of Rajah Humabon. The mission was now teetering on disaster and João Lopes de Carvalho took command of the fleet and led it on a meandering journey through the Philippine archipelago.

During the six-month listless journey after Magellan died, and before reaching the Moluccas, Elcano's stature grew as the men became disillusioned with the weak leadership of Carvalho. The two ships, Victoria and Trinidad finally reached their destination, the Moluccas, on 6 November. They rested and re-supplied in this haven, and filled their holds with the precious cargo of cloves and nutmeg. On 18 December, the ships were ready to leave. Trinidad sprang a leak, and was unable to be repaired. Carvalho stayed with the ship along with 52 others hoping to return later.[41]

Victoria, commanded by Elcano along with 17 other European survivors of the 240 man expedition and 4 (survivors out of 13) Timorese Asians continued its westward voyage to Spain crossing the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. They eventually reached Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 6 September 1522.[42]

Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian scholar, was a crew member of the Magellan and Elcano expedition. He wrote several documents about the events of the expedition. According to Pigafetta the voyage covered 14,460 leagues – about 81,449 kilometres (50,610 mi).

Elcano under Magellan's leadership

Ferdinand Magellan was the expedition leader, the captain general. Being Portuguese, he had traveled in his youth through South Asia with the Portuguese army, getting to know those islands, establishing safe harbors and places to stay and establishing the mastery of the maritime routes for trade. As a result of those experiences, Magellan knew the exact location of the Moluccas islands, or made King Charles V believe this. And he claimed (he was wrong) that they were in the Castilian zone, following the Treaty of Tordesillas. He was named captain general because he had this information. And that is why he was responsible for the route of the expedition.

The relationship between Magellan and Elcano quickly became strained, precisely because Magellan did not want to show anyone the route and did not want to tell anyone exactly where the Moluccas were.[6][27] Magellan condemned Elcano in San Julian (Patagonia) for his participation in the San Julian revolt.

It is known that Elcano was afraid of Magellan for having confessed in the interrogation in Valladolid after the circumnavigation. And he added that that was why he had not written anything while Magellan was alive, because he was afraid of him.[6] Magellan was killed in the Philippines on April 27, 1521 by fighters from the island of Mactan.

Although the objective set by the king was to open the spice road, when they reached Asia the personal objectives of Magellan as a caption aroused. The king promised Magellan to make him Governor of those islands in the Castilian region and to enjoy the commercial rights of two main islands. Probably for this reason, the expedition did not go directly to the Moluccas islands, to take spices, but further north. And they also traveled the area from one side to the other, participating in the internal conflicts of their peoples.[27]

The travel after Magellan's death

After Magellan's death, the Portuguese Duarte Barbosa, a relative of Magellan, was appointed captain general, but he was also killed in Cebu together with Captain João Serrão, of the Trinidad, in a dinner-trap organized by the Hindu leader of the island, the rajah called Humabon. In that ambush on May 1 and in Mactan, several sailors lost their lives, about 35 people.[27] In this situation, on May 2, 1521, it was decided to burn the ship Concepción because there were not enough sailors, some 116 or 117, to take charge of the 3. Thus, the expedition was reduced from five to two vessels.[6][27]

They only had two vessels to return to Seville: Victoria and Trinidad. However, Elcano was not immediately appointed captain. First another Portuguese, Juan Lopez de Carvalho, was installed in May 1521. In disagreement with Carvalho's manner of command, the sailors at the stern dismissed Carvalho and put Elcano as captain of the ship on September 17, 1521.[6] Clarifying what happened between May and September is complicated because there are several versions. How or why the unusual decision was made to remove Carvalho and put Elcano on board has not yet been fully clarified. But it is certain that Elcano was elected captain by the stern crew to replace Carvalho.[33]

After arriving in the Moluccas and loading the clove, once in South Asia Captain Elcano changes his original plan. He will propose to go forward, to continue westward, to return to Europe through southern Africa, without turning back or passing through southern America. And this change of plans will be the culmination of the first round-the-world voyage.

From Tidore to Cape Verde

They finally reached the Molucca Islands, specifically the island of Tidore, in present-day Indonesia. There they found the precious spice they were looking for, the clove. They made a deal with the king or rajah, who they called Almansur of Tidore Island, who brought them tons of cloves. The Victoria, for example, brought 27 tons of cloves to Seville. As there were not so many cloves on Tidore Island, they had them brought from the neighboring islands as well. In the meantime, the Trinidad broke down. As they heard that the Portuguese were approaching, because of the danger of waiting, they decided to return alone on the Victoria, with Elcano as captain.[27] However, they had the exact order to return by the way they had gone, an order they did not comply with.[6][33] They took the westward course with the idea of sailing around the world. Elcano proposed to sail around the world because, as he indicated, "They were going to do what could be narrated". Some say that he did it precisely for that reason, because Elcano had that historical conscience, as is clear in the letter he wrote to the newly arrived King:[43]

Your Majesty will know that we should have the highest esteem for having discovered and encircled the roundness of the world, for we have gone to the West and returned by the East.

Elcano allowed the sailors to choose their ship. After all, they were to circumnavigate the waters belonging to Portugal. 47 sailors chose to return with Elcano aboard the Victoria, and 13 members decided to stay in the Moluccas. At that time there were twelve Basques left in the expedition, of whom eight decided to return with Elcano, the other three remaining on board the Trinidad. The ship Victoria left Tidore Island on December 21, 1521, bound for Seville. Immediately a strong storm hit them and ruined the ship. On the nearby island of Mallua (today called Pulau Wetar) they had to stay 15 days for repairs. From Tidore they sailed to the island of Timor, and after spending a few days there, they set sail on February 7, 1522. From that day until July 9, when they reached Cape Verde, they would not set foot on land again.[27]

The journey from Timor to Seville was 27,000 kilometers long, and they planned to sail without making a stopover. They will not succeed, of course, because after over 20,000 kilometers, the sailors will have to decide to stay in Cape Verde, by vote, because the situation was impossible. In order not to meet the Portuguese on the way, they crossed it to the southern hemisphere, far south, avoiding India. Moreover, by going so far south, they also managed to avoid the opposing monsoon winds that at that time of the year came from Africa. They sailed very close to Australia, about 500 km away. If instead of sailing southwest they had sailed south in a straight line, they would have reached Australia in two or three days of sailing. As the days went by, the food also began to run out. When they had only rice cooked in seawater to eat, scurvy began to make the sailors seriously ill. Under these circumstances, the idea of making landfall in Mozambique spread on the ship. It was dangerous to dock, however, because the armies of Portugal could capture them. Elcano asked all the sailors and, surprisingly, it was decided by vote to go ahead, without staying in Mozambique.[6][27]

Crossing the southern tip of Africa, the perilous Cape of Good Hope, was very difficult for them. The Portuguese called it 'the cape of storms'. At first they headed south, to take advantage of the wind, but the ship could not move forward because they had been hit by extreme bad weather (the usual in those parts). For nine weeks they stayed there, frozen to death, with their sails lowered.[44] At last Elcano made the sailors a very dangerous proposition: to pass the cape close to the coast. One danger was that the storms would push the proud. To find the Portuguese on the other. But they did so, and at last managed to turn the cape and head northward past Africa.[6][27]

Landing in Cape Verde

They could not make it directly to Seville because the situation on board was already absolutely deplorable. They needed to stop somewhere. In desperation, and in search of food, they first tried to call at the African coast (off Guinea Bissau and Senegal), but could not find a suitable place to dock. Desperate, they decided to call at Cape Verde, voting among all the sailors. It was the last part of the voyage, and although the Portuguese were in charge in Cape Verde, they had not made landfall for months, with two or three deaths a week. Because of the mollusk called Teredo navalis was eating the wood of the ship, water was getting in through the holes in their vessels, and as they had nothing to eat, and there were fewer and fewer of them, they did not have the strength to pump the water out of the ship. Determined to need food and help, they decided to ask for it in Cape Verde.[27]

To make matters worse, they had nothing with which to make the exchange, for they had nothing but cloves. But the exhibition of the clove would reveal the origin of the expedition (i.e., that the ship was not returning from America, but from Asia) and the Portuguese would come out against them. Somehow they were able to pay for the first two cargoes in search of food, but when paying for the third they used cloves and realized the identity of the Portuguese. This assumption has been dismissed by scholars as Santamaría, who argue that this kind of errors wouldn't be possible.[6] They then had to flee, followed by the Portuguese. They were going to leave 13 sailors, prisoners of the Portuguese, in Cape Verde.

It is not entirely clear whether the cause of the dangerous third binge at Cape Verde was to obtain food, or slaves. Most of the original accounts (including Elcano's) speak only of food, but Bustamante (the doctor-barber on board) says that they went down to look for slaves because of the imperative need for labor power to pump the water.[33] This could be because the African slave trade was common and legal in Portugal.

Arrival

They didn't make the passage from Cape Verde to Seville in a straight line because the wind was pulling them down. They turned around by 'Volta do mar largo', taking a wide course to the west, to go up almost as far as Galicia and from there down to enter Seville. They returned to Sanlúcar de Barrameda on September 6, 1522, and two days later, they entered Seville on September 8, after almost three years of crossing. Of the 234 (or 247) sailors who set sail, only 18 arrived.[27]

As soon as the ship Victoria arrived in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Elcano set down on writing a 700-word letter addressed to Charles V, where he never mentions himself. He emphasized on it that they had achieved their goal to carry back the spices, "brought peace" to these islands, and obtained the friendship of their kings and lords, also bringing along their signatures.[43] He went on to highlight the extreme hardships undergone during the expedition. Elcano did not forget the members of the crew captured in Cabo Verde by the Portuguese, begging the emperor to initiate all necessary actions leading to their release. He ends the letter with commentary about their discoveries, the roundness of the world, setting sail to the west and coming back from the east.[43]

After the voyage

Court of Valladolid

Once the voyage was over, upon arriving in Seville, the sailors took the road to the court of Valladolid. At that time, Valladolid was the residence or court of Emperor Charles. The Emperor himself wanted Elcano to tell about the expedition. In the letter of invitation written by the king, he offered them horses to make the trip. The invitation, in reality, was only for Elcano and two others, Those who have better sense. Elcano, however, took more members with him. The little group arrived in Valladolid, including the 3 sailors from the Moluccas, because they wanted to meet the King. One might think, then, that the Seville-Valladolid stretch was traveled more by carriage than on horseback.[33]

King Charles V received Elcano soon, at the latest one month after the end of the circumnavigation. Elcano spoke at the court of Valladolid, in the presence of the king, and gave the account of the voyage. Perhaps in three parts: first with the emperor, perhaps in private; then with the Court authorities, for technical and economic matters, and also to clarify the police-military, deaths, insurrectionists, etcetera. And, finally, with a group of humanists more interested in culture. It is not known exactly how these meetings went.[45] He would spend three years in Valladolid, near the Court. There he joined María Bidaurreta (in some sources De Vida Urreta) and had another daughter.

Emperor Charles V granted Elcano an augmentation of his coat of arms featuring a world globe with the words Primus circumdedisti me (Latin: "You first encircled me");.[46] However, this augmentation has been contested, as he wasn't noble before. Elcano reclaimed and received from the emperor three gifts as a reward for his achievement, namely an annual pension of 500 ducats, two armed men to escort him and an official statement pardoning him for the sale of his ship to the Savoyard bankers; however, following Elcano's death and long lawsuits, his mother Catalina del Puerto did not manage to receive any pensions. By 1567, after Elcano's mother demise, relatives of Juan Sebastian and heirs kept demanding the pension.[47] His family were given rule over the Marquisate of Buglas in Negros Island, Philippines.[48][better source needed] In the modern era, the country with the most people surnamed "Elcano" is currently the Philippines.[49]

Relations with Portugal

The king of Portugal, John III, filed a piracy complaint against Elcano for the theft of the clove in the Moluccas and his escape from Cape Verde. He petitioned the King of Castile to return the clove and to arrest and punish Elcano. King Charles V protected Elcano and disregarded the request of the King of Portugal.

Portugal and Castile claimed the Moluccas Islands. The need to revise the Treaty of Tordesillas was not easy to resolve. Without knowing the exact size of the world, it was difficult to place those islands in a certain area. The key was to know where the anti-meridian passed behind the meridian established in the Treaty of Tordesillas, in order to know on which side the Moluccas Islands were located. Meetings to resolve the matter were held in 1524 in the Spain-Portugal border towns of Elvas and Badajoz. Five of the six Basques who circumnavigated the world participated in these assemblies.[50]

To accurately establish this antimeridian, each Crown took the best cosmographers of the time. Each delegation appointed three astronomers or cartographers, three sea pilots and three mathematicians. The Spanish delegation also took Fernando Colón, son of Christopher Columbus, with the objective of determining the location of the Moluccas. The negotiating team included Sebastián Caboto, Juan Vespucio, Diogo Ribeiro, Estêvão Gomezs, Simón Alcazaba and Diego López de Sigueiro.[51]

In the Badajoz-Elvas assemblies, the most authoritative voice of the Castilian delegation will be Elcano himself, who will devote himself to his work as a cosmographer. He will bring to these meetings a sphere of the world made by him. It is said that on that sphere he had marked the trajectory of the world tour. These meetings were unsuccessful because they could not agree on the exact location of the Moluccas Islands. The Portuguese did not recognize Elcano's authority, because from the voyage made once an exact location of the islands could not be deduced. We do not know exactly why, but suddenly Elcano (and the pilot Estêvão Gomes) were absent from those meetings on March 15, 1524. Shortly thereafter, the king gave his support to Elcano on May 20, 1524, as it was said that there were those who wanted to harm him (the royal charter speaks of "wounded, dead or crippled"), and three days later, on May 23, 1524, they met again in Badajoz, but without Elcano. The hypothesis is that he was threatened by the Portuguese in the case of the Moluccas. In October 1524 Elcano was in the Basque Country preparing for the second expedition to the Moluccas.[35] As they did not agree on the location of the Moluccas, two years later, in 1526, they will sign the Treaty of Zaragoza. Castile will recognize the Moluccas as being on the Portuguese side for 350,000 ducats.

Loaísa expedition

In 1525, Elcano returned to sea, and became a member of the Loaísa expedition. He was appointed leader along with García Jofre de Loaísa as captains, who commanded seven ships and sent to claim the East Indies for the emperor Charles V, a movement that was unpleasent for Portugal.[52] Elcano joined this expedition, as substitute and main pilot for Loaisa, aboard the Sancti Spiritus[20]. Elcano was the one with experience, but the emperor chose García Jofre de Loaisa as the person in charge because he was a nobleman and the objective was to create an authority over the Moluccas.[53] He was accompanied by the brothers Martín Pérez, Ochoa Martínez and Antón, his brother-in-law Gebara and his nephew Esteban Mutio.[54]

Elcano's influence was evident in the preparations for the expedition. Of the seven ships, 4 had been made in Basque territory and the number of citizens of the Gipuzkoan coast had increased considerably, even in positions of responsibility, compared to the first expedition. Many of them were close to Elcano.[24]

A cursed expedition

The new army of the Moluccas, that of Loaisa, sailed from A Coruña on July 24, 1525 with six ships and faced all kinds of misfortunes. Before reaching the strait, two vessels were lost, because they couldn't find the entrance to the strait. The Sancti Spiritus, piloted by Elcano, was lost in a storm, and the San Gabriel deserted, returning to Castile along the Brazilian coast. They finally crossed the Strait of Magellan on May 26, 1526, and set out for the Pacific crossing. A storm scattered the ships on June 2 and only one, Victoria, remained. One of the ships ended up in Zihuatanejo, Mexico.

The ship continued to the Moluccas in poor condition and suffered the ravages of scurvy on the part of the crew. The accountant Alonso de Tejada, the pilot Antonio Bermejo and thirty-two other crew members died. Finally, General Loaisa himself died on July 30. Elcano then took command of the navigation, and was named Captain General, a position he had entrusted to the king from the beginning. But for a short time, as he died of scurvy, probably on August 6, 1526. All his relatives who accompanied Elcano also died, except, perhaps, could be his brother Otxoa Martínez, because of his arrival in Zihuatanejo. And in one of the documents that appeared later in Laurgain, dated January 29, 1529, the king calls "Johan Ochoa Martínez del Cano" to go on the expedition of Simón de Alcazaba to the Moluccas. If he is his brother, in 1529 he was still alive. Before dying, he made a will. One of those who signed as witnesses in the will was Andrés de Urdaneta.

On August 7, his body was thrown into the water. Elcano's body was wrapped in a shroud and tied to a board with ropes. Afterwards, it was placed on the deck of the ship while praying the "Lord's Prayer" and "Hail Mary". When they finished, a weight was tied to the shroud, and Alonso de Salazar, the new captain general of the Army, nodded his head. The four sailors leaned the plank over the gunwale and tilted it, until the weight of the corpse was directed by itself towards the sea.[20]

Writings by Elcano

Few documents have come down to us in his handwriting. Only two letters addressed to King Charles and a will. In the interrogations of Seville (before the expedition) and Valladolid (after the expedition) the answers given by Elcano were also recorded in writing and have also reached us. Elcano's voice can be heard in them.

However, we know that he wrote at least one other text: the travel chronicle of the world tour. While Magellan was alive Elcano did not write anything because he was afraid of him (in the Valladolid interrogations, Elcano answered that). After Magellan's death, however, after Elcano's appointment as captain, he began to write down (as he himself said in the Valladolid interrogation) what had happened and what he had seen.

That account of the first world tour written by Elcano has been lost. Along with Elcano's account, the other most important written chronicles of the voyage, such as Magellan's or Pigaffeta's original, are also lost.[6][34] However, in the case of Magellan and Elcano it has been proposed that both writings could be translated in the Latin chronicle of the royal secretary Maximilianus Transilvanus. The hypothesis is that the main passages of the chronicle written by Elcano have come down to us in the contemporary chronicles rewritten by Maximiliano Transilvano and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo.[33]

First Letter to the Emperor

The first letter was written in Sanlúcar de Barrameda to let the Emperor know that he has arrived from his circumnavigation. The text is precise and correct, as merchants and not diplomats usually write. He promises the Emperor elements to account for the success: documents, letters of submission from the monarchs of the remote island and samples of spices. In addition, he brings with him five parrots, highly appreciated at the Court. He explains in 10 lines what happened up to the death of Magellan and, subsequently, what happened in his charge in the other 40-45. It is at that moment when he asks him to make an effort to free the 13 who have been detained in Cape Verde. He asks for a financial reward from the emperor, but mentions that the feat accomplished was a collective decision.[45]

Second Letter to the Emperor

The purpose of the second letter is to ask for bonuses. Approximately 40 days after arriving from sailing around the world, he arrived at the Court of Valladolid, the King received the request to name Elcano Captain General. In it he also asks him to have the commercial rights of the Moluccas or the habit of the Order of Santiago, which were entrusted by the King to Magellan. The King's secretary (Francisco de los Cobos) denied all of them. Apparently, in the Court of Castile they did not respect him too much, and they did not want to give Elcano the orders that had been promised to Magellan.[45] Santamaría argues that this animaversion was caused by Elcano's lack of nobility.[6]

It took him months to obtain the other 3 bonuses -pension, pardon and right to arms-, probably as a result of the rapprochement with the Court.[45]

Will of Elcano

The will is also an interesting source of information about Elcano. In addition to citing all his assets for being in the middle of the Pacific in excruciating detail, he also talks about his family. Thanks to the will it can be seen that, although he never married, he was with at least two women. Both Basque or of Basque origin. He had two children, one with each of them. He had his son (Domingo) before the world tour and his daughter after the world tour.[33]

The will was drawn up on July 26, 1526 and opened by the president of the Council of the Indies upon his arrival in Seville, ten years after it was drawn up.[55] All seven witnesses to the will were Basques, which is also surprising, given the situation and location, in the middle of the Pacific, a clear indication of trust and solidarity among them.[33] The witnesses were Martín García Karkizano, Andrés Gorostiaga, Hernando Gebara, Andrés Urdaneta, Juanes Zabala, Martín Uriarte and Andrés Aletxe.[43]

In his will he gave money to churches such as San Salvador de Getaria, Itziar, Sasiola (Deba), Our Lady of Arantzazu, San Pelayo in Zarautz or Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Hondarribia. However, he asked that all this money should at some time come out of the money to be paid by the king, something that had never happened.[43] This move of only giving money to the church if the King payed has been used by Santamaría to dismiss the idea of Elcano being a very religious man.[6]

To the heirs he also lent that money, but if they died (as it happened) he gave his mother the benefit of his properties. He treated the four of them generously in the distribution of goods: one hundred ducats of gold to Domingo's mother (37,500 maravedís) and another 40 ducats (15,000 maravedís) to the daughter, if she married, as a dowry. On the other hand, he requests the effort of his daughter to take her from Valladolid to Getaria when she turns 4 years old, if necessary, because Getaria was more beloved than the Court of Valladolid.[43]

We also know, thanks to the will, that she had two books in Latin, so he knew how to read in that language.[33] Both books refer to astronomy, one the Regiomontanus Almanac,[56] which allowed to solve the problem of longitude at sea with the Moon.[57] These two books were left to Andres San Martin, his pilot cosmographer who disappeared on the circumnavigation, if he was found alive. This suggests that in the second expedition Elcano was still hoping to find alive the companion lost in the first expedition.[33]

In 1533, seven years after Elcano's death, his mother was still in court with the royal treasury for the salaries due to her son and for the fees he did not receive, corresponding to the rank of captain, and also for the pension of 500 ducats per year.[43] The will also shows that Elcano did not have slaves, otherwise he would have to cite them.

Transilvanus' text

The humanist Maximilianus Transylvanus was at Court listening to Elcano. In the fewer weeks he wrote the chronicle that became famous, in the form of a letter, which he sent to his patron, Matteo Lang von Wellenburg. The book was printed in Cologne in January 1523 and in November of that year another printing was made in Rome by Gian Matteo Giberti, assistant to Pope Clement VII. Giovanni Battista Ramusio years later made a collection of travels and introduced the text of Transilvanus. The text was written in Latin, for political purposes and according to the tastes of Chancellor Gattinara.[45] It is possible that this text of Transilvano is directly a compilation of collected testimonies: in fact, the account of Magellan's part is very different from that of Elcano's part, as if it had different authors. Moreover, another chronicler of the time who read these two texts, Fernandez de Oviedo, also alluded to the parity between the texts of Elcano and Transilvano: "It is almost him", he wrote.[6][33]

If the second part of the Transylvanian text were that of Elcano, it would be another exponent of the humanist and utopian current that was then being forged in Europe, as well as one of the first principles of the myth of the noble savage and a criticism of the corruption of European civilization.[33] The text also says that they are peaceful civilizations, which treated their neighbors well and even better to foreigners:[58]

All of them show great respect and care not to cause harm or discomfort to neighboring towns, even more so to neighbors from neighboring islands, and even more so to foreigners or pilgrims.

If the text of Transilvano is written by Elcano, it is interesting because it makes a utopian description of the island of Borneo. In it, in Borneo, he sees that the Europeans were not the only civilization and it becomes evident that he looked at those countries without evangelizing vanity. The description draws a utopian vision. Not much is said about the events in Borneo; that they talked to the local king, made some exchanges and moved on. What they were doing there is not explained in the passage, although it is known, Borneo, that it was a place of conflict for the travelers. Thus, it can be observed that the writer is speaking more of his utopian vision than of the description of Borneo.[33] In the text about Borneo there's a critic to war-seeking kings and a relation about paganism and peaceful societies.[58]

Historiography

Elcano's achievement has been somehow eclipsed in traditional historiography by Magellan who planned and led the famous expedition until his death before reaching the Spice Islands. More recently, Portugal's solo candidacy to UNESCO to get Magellan's expedition and the resulting circumnavigation (without mentioning Elcano) recognised as a Portuguese Intangible World Heritage has provoked a major controversy with Spain, thereafter seemingly settled by the submission by said countries of a new joint application to honour the circumnavigation route.[59] Elcano has been, in a way, a secondary character in world history. In the Basque Country the knowledge about Elcano has been greater.[60]

Elcano, deleted from History

Throughout the world Elcano has been a marginal character because he was almost forgotten for three centuries. In the first accounts of the voyage, the cold reception that the world tour had at the Court of Castile is noticeable; in the long seventeen-page account written by Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, for example, Elcano was not mentioned even once. The reason for the disparagement is perhaps that those who sailed around the world were not hidalgos, but common sailors, a fact that goes against the late medieval mentality.[61]

Nor did Antonio Pigafetta, who had completed the chronicle of the voyage from the ship, seem to mention Elcano.[62][63] In the chronicle of Pigafetta that has come down to us, the chronicler exaggerates and perhaps that is why in Italian historiography Elcano disappears and Capitano Pigafetta himself appears as an important character.[64][6]

In recent years, however, another point of view has spread: Pigafetta quoted Elcano, but as the works of Pigafetta that have reached us today are totally modified, perhaps the mentions to Elcano were suppressed. In fact, the original Pigafetta chronicle is lost. Moreover, the account that has come down to us would be a retranslation of a translation made in France, written later, and suppressing or modifying many sections. The hypothesis is that, since France was at war with Castile, the French eliminated all the "Spaniards" that Pigafetta praised.[6][64] This 'eliminatory' view was further extended when it was written by Philip II's chronicler, embellishing more the hidalgos (Magellan and Pigafetta) and forgetting the plebeians. Spain turned Magellan into a figure in favor of the unity of Portugal and Spain: he betrayed Portugal by becoming Castilian. Thus, he became a hero for the Castilians who acquired political strength.[33][61]

It was in the interest of Castile to elevate Magellan (and to push Elcano aside), but also of the Catholic Church. The tug of war between the empire of Charles V and the Roman Catholic Church was constant. The Holy Roman Empire presented itself as a Catholic Empire, but at the same time it did not control the center of religion (Rome). The Church did not want Charles V to have too much power. Thus, the Church will want to mark a contrast between the bloody evangelization that Spain carried out in America and the peaceful evangelization that Portugal carried out in Asia. Since it was convenient to emphasize that Spain's attempt at evangelization was impregnated with blood, while Portugal's was a builder of civilization, it was good for the Church to praise Magellan. Thus, Magellan was praised by Rome and England, allied with Portugal against Spain. Magellan was taken as a model of civilization, and Francis Drake as the executor of his dream, even claiming that he really had sailed around the world.[6][61]

Although many technical and economic documents have arrived, most of the originals have disappeared. We know that they existed because these documents are cited by those who received the facts of those times. Neither the chronicle of Elcano's voyage, nor the trial against Carvalho, nor the documentation provided by Elcano at the Badajoz-Elvas meetings, nor the ship's logbook are known. The Trinidad ship's book has also been lost, although it was taken by Portugal. According to historian Enrique Santamaría, these documents have been eliminated, probably in the 19th century, because having such a high value it is difficult to think that they have been lost, and because documents with many other details of the voyage have arrived.[6]

Navarrete's account

In the context of the Napoleonic Wars, feelings of nationalism arose in most European countries. In Spain this sentiment had a conservative component. In that retrospective, Spain had to build its new historiography, in which Martín Fernández de Navarrete was director of the Royal Academy of History. Martín Fernández de Navarrete wrote in 1825 a modern 'official' account of the world tour, "Colección de los viajes y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles", in which Magellan is still praised. The figure of Elcano that has come down to us will begin to be constructed.[6]

At a time when Spain was experiencing the decolonization of America, the country needed a message against its citizens and in favor of its elites. Magellan turned into an excellent example of those elites who must fight against the incapacity of common men to understand: noble, in favor of the king, evangelist and supporter of civilization. On the contrary, Elcano's form of command seemed despicable to Navarrete, who was in the habit of deciding the most important matters by vote, because he had never conquered, evangelized or civilized anyone, nor had he ever tried. Thus, in Navarrete's account it is noticeable that Elcano's completion of the world tour understood as an injustice or anomaly with Magellan's is an attempt to solve it.[65] From Navarrete's account, the historiography of Spain has subsequently spread, and at the international level this is the main view that has been considered as good.[6]

Later constructions

In 1861 the military Juan Cotarelo wrote the first biographies of Elcano. That marshal of the Spanish army tells us that Elcano was humble and obedient while the Basques fought in the Second Carlist War, that he had managed to sail around the world with a submissive character.[66] And he puts as proof that in the rigorous and rude Valladolid investigation on the Round the World Race, Elcano answered in the most humble way to the thirteen questions he was asked.[33]

Eustaquio Fernández de Navarrete, grandson of Martín Fernández de Navarrete, wrote a more complete biography of Elcano in 1872. This biography has a more 'scientific' character and has been the main reference for historians. As it was problematic that Elcano lacked "imperial pedigree", in order to vindicate his figure, Eustaquio Fdez de Navarrete suggested, without providing any proof, that Elcano had taken part in the Siege of Oran and in the Italian wars.[61]

From Cánovas to the Francoism

Elcano was a victim of the political game of the 19th century. Antonio Cánovas del Castillo faced the creation of peripheral nationalisms and fuerismo in a chaotic scenario after the First Spanish Republic. In his opinion, the foralists used history to defend their politics and, for this reason, he wanted to underestimate the shouting of the Basques and Navarrese in history. Thus, in addition to Elcano, he tried to forget Blas de Lezo, Churruca, Urdaneta or Legazpi, establishing a damnatio memoriae.[34] In order to eradicate Elcano again, Cánovas reinforced Magellan in the message that served to vindicate the political unity of the Iberian Peninsula. Elcano was no more than the "humble master" of the ship ("modesto maestre").[34]

Primo de Rivera, however, wanted to recover Elcano and named the ship Juan Sebastián de Elcano (A-71) after him. It was Franco's regime that tried to turn Elcano into a national myth, using the story of Eustaquio Fernández de Navarrete (1872).

Amado Melón Ruiz de Gordejuela in his book Magallanes o la Primera Vuelta al Mundo, published in 1940 in the collection La España Imperial, affirmed that Elcano participated in the siege of Oran and was an assistant to the Great Captain. Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordova campaigned in Italy between 1495 and 1504, and as they wanted to settle in Elcano Oran, they added 10 years to his age (otherwise he would have been 8 years old). Since then, they spread that Elcano was born in 1476 instead of 1487. With the new birth date, Elcano's participation in the Oran campaign has been published in all history books.[34][6]

500th anniversary

The 500th anniversary of the first circumnavigation is celebrated in 2022. In view of this, several initiatives have arisen, both to complete its history and memory (such as the Elkano Foundation) and to face the celebration of the event.[67][68]

As part of the commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the first circumnavigation of the Earth on the 6th of September 2022, the Basque Maritime Museo, with the support of the Elkano Foundation, has published a new book: Elcano and the Basque Country. How the First Round the World was made possible (June 2022).[69]

Elcano in art

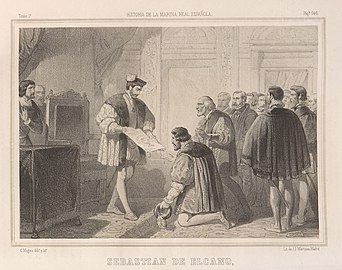

There is no description or contemporary artwork depicting Elcano. All the artworks were made centuries later and, therefore, have invented factions and clothing.

Paintings

-

Juan Sebastian Elcano, and his birthpace, Getaria by Ignacio Zuloaga. The depicted man is the doctor Pío Gogorza.[70]

-

José Ferrer de Couto's engraving

-

Las glorias nacionales, by the printer Luis Tasso, 1852.

-

José Ferrer de Couto's engraving

-

Elkano's gift, by Elías Salaberria, 1924.

Banknotes

-

500 peseta, 1931, based on Elias Salaberria's painting.

-

500 peseta, 1931

-

Note of 5 pesetas from 1948, based on Ignacio Zuloaga's painting.

Sculptures

-

Elcano's statue in Getaria (1881).

-

Sculpture at Passeig de Gràcia, Barcelona.

-

Monument in Seville.

-

Sculpture by Carlos Palao, in Getaria.

-

Monument dedicated to Elcano in Getaria.

-

Palace of Gipuzkoa, Donostia.

Cinema

In 2019 an animation movie was made in Basque language by Ángel Alonso with the title Elkano, lehen mundu bira[71]. In 2020 another animation movie by Manuel H. Martin called El viaje más largo was presented in Sevilla. In 2022 Amazon Prime broadcasted the series Boundless, with Álvaro Morte as Elcano[72].

See also

Notes

- ^ Some sources state that he was born on 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean when we was a child. According to his own answer of the age he had when he boarded the expedition, he was born 10 years later, around 1486 or 1487.

- ^ Elcano was Basque, as was noted also by other members of the expedition. Martín de Ayamonte, in his relation to the Portuguese inquity, clearly said that the captain was Biscayne.[5][6]. Modern sources also state this[7][8][9][10][11].

References

- ^ a b Múgica Zufiría, Serapio (1920). "Elcano y no Cano" [Elcano and not Cano]. Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos (in Spanish). 11: 194–213.

- ^ Euskaltzandia (2021). "'Juan Sebastian Elkano' idaztea hobetsi du Euskaltzaindiko Onomastika Batzordeak". www.euskaltzaindia.eus (in Basque). Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ a b c Aguinagalde, F. Borja (2018). "El archivo personal de Juan Sebastián de Elcano (1487-1526), Marino de Getaria" (PDF). IMO. In Medio Orbe 1519-1522 (in Spanish) (1). ISSN 2659-3556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Juan Sebastián Elcano. Biografía". Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ "Testimonio de Martín de Ayamonte". primeravueltalmundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Santamaría Urtiaga, Enrique (2022). La vuelta de Elkano. El molesto triunfo de la gente corriente (in Spanish). Donostia: Eusko Ikaskuntza. ISBN 9788484193012.

- ^ "Juan Sebastián Elcano, el vasco que dio la vuelta a la historia". El Correo (in Spanish). 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ^ "Magellan got the credit, but this man was first to sail around the world". History. 2022-08-31. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ^ Woodworth, Paddy (2008). The Basque Country : a Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-804394-2. OCLC 727949806.

- ^ "Juan Sebastián del Cano | Spanish navigator | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ Zulaika, D. (2019). "Elcano, los vascos y la primera vuelta al mundo" (PDF) (in Spanish). Kutxa Kultur.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Totoricagüena, Gloria Pilar (2005). Basque Diaspora: Migration And Transnational Identity. University of Nevada Press. p. 132. ISBN 9781877802454.

- ^ Facaros, Dana; Pauls, Michael (2008). Bilbao & the Basque Lands. Cadogan Guide. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-86011-400-7.

- ^ Salmoral, Manuel Lucena (1982). Historia general de España y América: hasta fines del siglo XVI. El descubrimiento y la fundación de los reinos ultramarinos (in Spanish). Ediciones Rialp. p. 324. ISBN 978-84-321-2102-9. Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Michelina, Luis (1973). Apellidos vascos (3. ed. aum. y corr ed.). San Sebastián: Txertoa. ISBN 84-7148-008-5. OCLC 2774372.

- ^ "OEH - Bilaketa - OEH". www.euskaltzaindia.eus. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ "Euskaltzaindiaren Hiztegia". www.euskaltzaindia.eus. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ Isasti, Fernando Txueka (2018). "Juan Sebastián de Elcano desde la atalaya de Getaria". Boletín de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País (in Spanish). 74 (1–2). ISSN 0211-111X.

- ^ "Person - Elcano, Domingo Sebastián de". PARES. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Juan Sebastián Elcano | Real Academia de la Historia". dbe.rah.es. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ Kelsey, Harry (2016). The first circumnavigators: unsung heroes of the age of discovery. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-22086-5. OCLC 950613571.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Arveras, Daniel (2019-03-23). "El Testamento de Elcano". academiaplay (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ "'Paradoxa da Elkanok munduari bira ematea eta munduan ezezaguna izatea'". EITB (in Basque). Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ a b c Azpiazu, José Antonio (2021). Juan Sebastian Elkano: ingurua, ibilbidea, epika. Javier Elorza Maiztegui, Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País. Donostia: Euskalerriaren Adiskideen Elkartea = Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País. ISBN 978-84-09-31292-4. OCLC 1264407757.

- ^ a b c Congreso Internacional sobre la I Vuelta al Mundo 2016 Sanlúcar de Barrameda (2016). In Medio Orbe Sanlúcar de Barrameda y la I Vuelta al Mundo ; actas del I Congreso Internacional sobre la I Vuelta al Mundo, celebrado en Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz) los días 26 y 27 de septiembre de 2016. Carmen Jurado Tejero, Francisco Riesco García, Diego Bejarano Gueimúndez, Consejería de Cultura Sevilla Junta de Andalucia, Congreso Internacional sobre la I Vuelta al Mundo 2016.09.26-27 Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Cádiz. ISBN 978-84-9959-231-2. OCLC 1020317693.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Cervantes, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de (1837). "Coleccion de los viajes y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles desde fines del siglo XV: con varios documentos inéditos concernientes á la historia de la Marina Castellana y de los Establecimientos Españoles de Indias. Tomo 4. Expediciones al Maluco; Viaje de Magallanes y de Elcano" (in Spanish).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mazón Serrano, Tomás (2020). Elcano, viaje a la historia. Braulio Vázquez Campos. Madrid. ISBN 978-84-1339-023-9. OCLC 1201190903.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Amando., Melón y Ruiz de Gordejuela (1940). Magallanes-Elcano, o, La primera vuelta al mundo. Luz. OCLC 807205942.

- ^ Bernal, Cristobal (2019). Información hecha a instancias de Fernando de Magallanes y Relación de la Gente que llevó al descubrimiento de la Especiería o Moluco (PDF) (in Spanish). Patronato V centenario.

- ^ De Mariana, Juan (1601). Historia General de España.

- ^ Bira, Elkanori. "Historia ez da borobila" (in Basque). Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ "Elkano, Juan Sebastian (14..-1526) - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus (in Basque). Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Txapartegi, Ekai (2020-10-07). "Elkanotar Juan Sebastian, Pizkundeko humanista utopikoa?". Gogoa (in Basque). 21: 61–99. doi:10.1387/gogoa.22118. ISSN 2444-3573. S2CID 225155568.

- ^ a b c d e f Santamaría, Enrique (2020). "Elkano, breve relación de la evolución y las motivaciones de una catástrofe historiográfica (4/5): la hegemonía nacionalista".

- ^ a b c d Azpiazu, José Antonio (2021). Juan Sebastian Elkano: ingurua, ibilbidea, epika = Juan Sebastián de Elcano: entorno, trayectoria, épica. Javier Elorza Maiztegui, Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País. [Donostia]: Euskalerriaren Adiskideen Elkartea = Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País. ISBN 978-84-09-31292-4. OCLC 1264407757.

- ^ Berasaluze, Gari (2008). Elkano: itsasoak emandako bizitza. Dani Fano (1. argit ed.). Tafalla: Txalaparta. ISBN 978-84-8136-535-1. OCLC 863179867.

- ^ "La Primera Vuelta al Mundo. 1519- 1522 – Espacio I Vuelta al Mundo" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ "The crew". primeravueltalmundo. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ Zulaika, Daniel (2018). "Pedro de Tolosa, el grumete de la nao Victoria que dio la primera vuelta al mundo". Boletín de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País (in Spanish). 74 (1–2). ISSN 0211-111X.

- ^ Murphy, Patrick J.; Coye, Ray W. (2013). Mutiny and Its Bounty: Leadership Lessons from the Age of Discovery. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300170283.

- ^ Humble, Richard (1978). The Seafarers—The Explorers. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books.

- ^ Kattán-Ibarra, Juan (1995). Perspectivas Culturales de España [Cultural Perspectives of Spain] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). National Textbook. p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zulaika, Daniel (2019). Elkano, euskaldunak eta munduaren inguruko lehen itzulia (PDF) (in Basque). Mundubira 500 Elkano Fundazioa. p. 126. ISBN 978-84-09-12668-2. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Pigafetta, Antonio (2019). La primera vuelta al mundo : relación de la expedición de Magallanes y Elcano (1519-1522). Madrid: Alianza. ISBN 978-84-9181-757-4. OCLC 1135876720.

- ^ a b c d e Olaizola, Francisco de Borja de Aguinagalde (2019). "El capitán Juan Sebastián, o Elcano en su entorno. Guetaria, la circunnavegación y la corte del Emperador". Revista general de marina. 277 (8): 287–302. ISSN 0034-9569.

- ^ Sociedad de Bibliófilos Españoles (1892). Nobiliario de conquistadores de Indias (in Spanish). Madrid. p. 57 – via Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zulaika, Daniel (2019). Elkano, euskaldunak eta munduaren inguruko lehen itzulia (PDF) (in Basque). Mundubira 500 Elkano Fundazioa. pp. 129, 135–136. ISBN 978-84-09-12668-2. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A Plymouth' Monday". photoleraclaudinha.com. 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Elcano". forebears.io.

- ^ Zulaika Aristi, Daniel (2019). Elkano, euskaldunak eta munduaren inguruko lehen itzulia (Lehen edizioa: 2019ko ekaina ed.). Getaria. ISBN 978-84-09-12668-2. OCLC 1192390122.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "1524, el año en el que el reparto del mundo se acordó en Vitoria". El Correo (in Spanish). 2019-07-21. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ Sánchez-Pedreño, Jose María Ortuño (2003). "Estudio histórico-jurídico de expedición de García Jofre de Loaisa a las islas Molucas: la venta de los derechos sobre dichas islas a Portugal por Carlos I de España". Anales de derecho (21): 217–237. ISSN 1989-5992.

- ^ admin (2020-07-20). "La expedición de Jofre de Loaísa,el último viaje de Elcano". Tras la última frontera (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ Olaizola, Francisco de Borja de Aguinagalde (2017). "¿Qué sabemos realmente sobre Juan Sebastián Elcano?: resultados provisionales de una indagación llena de dificultades". In medio Orbe: Sanlúcar de Barrameda y la I Vuelta al Mundo: Actas del I Congreso Internacional sobre la I Vuelta al Mundo, celebrado en Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz) los días 26 y 27 de septiembre de 2016, 2017, ISBN 9788499592312, págs. 25-37. Junta de Andalucía: 25–37. ISBN 978-84-9959-231-2.

- ^ Tallafigo, Manuel Romero (2017). "La persona de Juan Sebastián de Elcano: su testamento". In medio Orbe: Sanlúcar de Barrameda y la I Vuelta al Mundo: Actas del I Congreso Internacional sobre la I Vuelta al Mundo, celebrado en Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz) los días 26 y 27 de septiembre de 2016, 2017, ISBN 9788499592312, págs. 39-53. Junta de Andalucía: 39–53. ISBN 978-84-9959-231-2.

- ^ Isasti, Fernando Txueka (2018). "Juan Sebastián de Elcano desde la atalaya de Getaria". Boletín de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País (in Spanish). 74 (1–2). ISSN 0211-111X.

- ^ "Johann Müller Regiomontanus y la reforma del calendario". www.astromia.com. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ a b ""De Moluccis Insulis", de Maximiliano Transilvano (adaptación)". V Centenario (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (20 September 2019). "Who First Circled the Globe? Not Magellan, Spain Wants You to Know". The New York Times.

- ^ Lonbide, Xabier Alberdi (2018). "Superación del "Síndrome de Elcano":". Boletín de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País (in Spanish). 74 (1–2). ISSN 0211-111X.

- ^ a b c d Santamaría, Enrique (August 5, 2020). "Elkano, breve relación de la evolución y las motivaciones de una catástrofe historiográfica (1/5)". Elkano Fundazioa.

- ^ Atlas de los exploradores españoles, Luis Conde-Salazar Infiesta, Manuel Lucena Giraldo, Barcelona: GeoPlaneta, 2009, ISBN 978-84-08-08683-3, OCLC 556943554, retrieved 2022-08-30

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Juan Sebastián Elcano: el mejor marino de la historia aún no tiene biografía". abc (in Spanish). 2018-03-21. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ a b Santamaría, Enrique (February 21, 2020). "El relato perdido de Pigafetta (1/2)". Elkano Fundazioa.

- ^ Toledo, Rodrigo González (2019). "Fernão de Magalhães/Fernando de Magallanes: un estado de la cuestión". Revista Historia Autónoma (15): 11–27. ISSN 2254-8726.

- ^ Garastazu, Juan Cotarelo (1861). Biografía de Juán Sebastián de Elcano (in Spanish). Imprenta de la Provincia.

- ^ "Nor gara?" (in Basque). Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Elkanori Bira herri ekimena sortu dute hainbat elkarte eta eragilek". El Diario Vasco (in Basque). 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2022-08-30.