Impossible trident: Difference between revisions

remove uncited claim |

m →top: Autowikibrowser cleanup, typo(s) fixed: ously- → ously |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|2D drawing of impossible 3D object}} |

|||

[[File:Poiuyt--opaque.svg|thumb|right|An impossible trident with backgrounds, to enhance the illusion]] |

[[File:Poiuyt--opaque.svg|thumb|right|upright|An impossible trident with backgrounds, to enhance the illusion]] |

||

[[File:RogerHaywardUndecidable Monument.jpg|thumb|right|[[Roger Hayward]]'s ''Undecidable Monument'']] |

[[File:RogerHaywardUndecidable Monument.jpg|thumb|right|upright|[[Roger Hayward]]'s ''Undecidable Monument'']] |

||

[[File:Impossible Trident Solution.jpg|thumb|right|'Impossible Trident Solution' by Peter Stott proposes that all parts of the image represent (portray) architectonic form (depict 3D objects) according to the rules of perspective.]] |

|||

An '''impossible trident''',<ref>Andrew M. Colman, ''A Dictionary of Psychology'', Oxford University Press, 2009, {{ISBN|0199534063}}, [https://books.google.com/books?id=XxGbsjKjPZsC&pg=PA369 p. 369]</ref> also known as an '''impossible fork''',<ref>[http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ImpossibleFork.html Article "Impossible Fork"] at MathWorld</ref> |

An '''impossible trident''',<ref>Andrew M. Colman, ''A Dictionary of Psychology'', Oxford University Press, 2009, {{ISBN|0199534063}}, [https://books.google.com/books?id=XxGbsjKjPZsC&pg=PA369 p. 369]</ref> also known as an '''impossible fork''',<ref>[http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ImpossibleFork.html Article "Impossible Fork"] at MathWorld</ref> '''blivet''',<ref>''[[The Hacker's Dictionary]]'', article "Blivet"; It lists the impossible fork among numerous meanings of the term</ref> '''poiuyt''', or '''devil's [[tuning fork]]''',<ref name=mk>Brooks Masterton, John M. Kennedy, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2199e5083_Building_the_Devil's_Tuning_Fork "Building the Devil's Tuning Fork"], ''Perception'', 1975, vol. 4, pp. 107-109</ref> is a drawing of an [[impossible object]] (undecipherable figure), a kind of an [[optical illusion]]. It appears to have three cylindrical prongs at one end which then mysteriously transform into two rectangular prongs at the other end. |

||

In 1964 D.H. Schuster reported that he noticed an ambiguous figure of a new kind in the advertising section of an aviation journal. He dubbed it a "three-stick [[clevis]]". He described the novelty as follows: "Unlike other ambiguous drawings, an actual shift in visual fixation is involved in its perception and resolution." |

In 1964, D.H. Schuster reported that he noticed an ambiguous figure of a new kind in the advertising section of an aviation journal. He dubbed it a "three-stick [[clevis]]". He described the novelty as follows: "Unlike other ambiguous drawings, an actual shift in visual fixation is involved in its perception and resolution."<ref>Schuster, D. H., "[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232573577_A_New_Ambiguous_Figure_A_Three-Stick_Clevis A New Ambiguous Figure: A Three-Stick Clevis."] ''Amer. J. Psychol.'' vol. 77, 1964, p.673, .</ref> |

||

The word "poiuyt" appeared on the March 1965 cover<ref>{{cite web |url=http://madcoversite.com/mad093.html |title=Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site - Mad #93 |publisher=Madcoversite.com |date |

The word "poiuyt" appeared on the March 1965 cover<ref>{{cite web |url=http://madcoversite.com/mad093.html |title=Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site - Mad #93 |publisher=Madcoversite.com |access-date=2010-10-22}}</ref> of ''[[Mad (magazine)|Mad]]'' magazine bearing the four-eyed [[Alfred E. Neuman]] balancing the impossible fork on his finger with caption "Introducing 'The Mad Poiuyt' " (the last six letters on the top row of [[QWERTY]] typewriters, right to left). An anonymously contributed version described as a "hole location gauge" was printed in the June 1964 issue of ''[[Analog Science Fiction and Fact]]'', with the comment that "this outrageous piece of draftsmanship evidently escaped from the Finagle & Diddle Engineering Works" (although something else called a "hole location gauge" had already been patented in 1961<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.freepatentsonline.com/2998656.html |title=Hole location gauge - Patent 2998656 |publisher=Freepatentsonline.com |date=1961-09-05 |access-date=2010-10-22}}</ref>). |

||

The term "blivet" for the impossible fork was popularized by ''[[Worm Runner's Digest]]'' magazine. In 1967 Harold Baldwin published there an article, "Building better blivets", in which he described the rules for the construction of drawings based on the impossible fork.<ref name=mk/><ref>William Perl,[https://books.google.com/books?id=NWpXAAAAMAAJ&q=baldwin+blivets |

The term "blivet" for the impossible fork was popularized by ''[[Worm Runner's Digest]]'' magazine. In 1967 Harold Baldwin published there an article, "Building better blivets", in which he described the rules for the construction of drawings based on the impossible fork.<ref name=mk/><ref>William Perl,[https://books.google.com/books?id=NWpXAAAAMAAJ&q=baldwin+blivets "Blivet or Not"], ''The Journal of Biological Psychology'', 1969</ref> |

||

In December 1968 American optical designer and artist [[Roger Hayward]] wrote a humorous submission "Blivets: Research and Development" for ''The Worm Runner's Digest'' in which he presented various drawings based on the blivet.<ref>{{cite book |title=Mathematical Circus |last=Gardner |first=Martin | |

In December 1968 American optical designer and artist [[Roger Hayward]] wrote a humorous submission "Blivets: Research and Development" for ''The Worm Runner's Digest'' in which he presented various drawings based on the blivet.<ref>{{cite book |title=Mathematical Circus |last=Gardner |first=Martin |author-link=Martin Gardner |publisher=[[Pelican Books]] |year=1981 |page=5}}</ref> He "explained" the term as follows: "The blivet was first discovered in 1892 in Pfulingen, Germany, by a cross-eyed dwarf named Erasmus Wolfgang Blivet."<ref>''Science, Sex, and Sacred Cows: Spoofs on Science from the Worm Runner's Digest'', 1971, [https://books.google.com/books?id=ItFfAAAAMAAJ&q=hayward+blivets pp. 91-93]</ref> He also published there a sequel, '' Blivets — the Makings''. |

||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

{{Sister bar|Blivet|wikt=blivet |commons=Category:Blivet|auto=1}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Sister project links| blivet|position=left|wikt=blivet |commons=Category:Blivet |b=no |n=no |q=no |s=no |v=no |voy=no |species=no |d=no}} |

|||

{{Optical illusions}} |

{{Optical illusions}} |

||

| Line 21: | Line 20: | ||

[[Category:Impossible objects]] |

[[Category:Impossible objects]] |

||

[[Category:Military humor]] |

[[Category:Military humor]] |

||

[[Category: Transcendental imaging]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 16:55, 20 May 2023

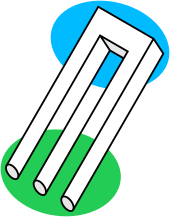

An impossible trident,[1] also known as an impossible fork,[2] blivet,[3] poiuyt, or devil's tuning fork,[4] is a drawing of an impossible object (undecipherable figure), a kind of an optical illusion. It appears to have three cylindrical prongs at one end which then mysteriously transform into two rectangular prongs at the other end.

In 1964, D.H. Schuster reported that he noticed an ambiguous figure of a new kind in the advertising section of an aviation journal. He dubbed it a "three-stick clevis". He described the novelty as follows: "Unlike other ambiguous drawings, an actual shift in visual fixation is involved in its perception and resolution."[5] The word "poiuyt" appeared on the March 1965 cover[6] of Mad magazine bearing the four-eyed Alfred E. Neuman balancing the impossible fork on his finger with caption "Introducing 'The Mad Poiuyt' " (the last six letters on the top row of QWERTY typewriters, right to left). An anonymously contributed version described as a "hole location gauge" was printed in the June 1964 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact, with the comment that "this outrageous piece of draftsmanship evidently escaped from the Finagle & Diddle Engineering Works" (although something else called a "hole location gauge" had already been patented in 1961[7]).

The term "blivet" for the impossible fork was popularized by Worm Runner's Digest magazine. In 1967 Harold Baldwin published there an article, "Building better blivets", in which he described the rules for the construction of drawings based on the impossible fork.[4][8] In December 1968 American optical designer and artist Roger Hayward wrote a humorous submission "Blivets: Research and Development" for The Worm Runner's Digest in which he presented various drawings based on the blivet.[9] He "explained" the term as follows: "The blivet was first discovered in 1892 in Pfulingen, Germany, by a cross-eyed dwarf named Erasmus Wolfgang Blivet."[10] He also published there a sequel, Blivets — the Makings.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Andrew M. Colman, A Dictionary of Psychology, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 0199534063, p. 369

- ^ Article "Impossible Fork" at MathWorld

- ^ The Hacker's Dictionary, article "Blivet"; It lists the impossible fork among numerous meanings of the term

- ^ a b Brooks Masterton, John M. Kennedy, "Building the Devil's Tuning Fork", Perception, 1975, vol. 4, pp. 107-109

- ^ Schuster, D. H., "A New Ambiguous Figure: A Three-Stick Clevis." Amer. J. Psychol. vol. 77, 1964, p.673, .

- ^ "Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site - Mad #93". Madcoversite.com. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "Hole location gauge - Patent 2998656". Freepatentsonline.com. 1961-09-05. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ William Perl,"Blivet or Not", The Journal of Biological Psychology, 1969

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1981). Mathematical Circus. Pelican Books. p. 5.

- ^ Science, Sex, and Sacred Cows: Spoofs on Science from the Worm Runner's Digest, 1971, pp. 91-93