Military recruitment: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: s2cid. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Headbomb | Linked from Wikipedia:WikiProject_Academic_Journals/Journals_cited_by_Wikipedia/Sandbox | #UCB_webform_linked 1009/1062 |

m Reverted edits by 79.148.115.183 (talk) (HG) (3.4.12) |

||

| (46 intermediate revisions by 34 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

=== Gender === |

=== Gender === |

||

{{Main|Women in the military by country}}{{See also|Women in the military|Transgender people and military service|Women in combat}} |

{{Main|Women in the military by country}}{{See also|Women in the military|Transgender people and military service|Women in combat}} |

||

Across the world, a large majority of recruits to state [[armed forces]] and [[Violent non-state actor|non-state armed groups]] are male. The proportion of female personnel varies internationally; for example, it is approximately 3% in India,<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://thediplomat.com/2016/02/indias-military-to-allow-women-in-combat-roles/|title=India's Military to Allow Women in Combat Roles|last=Franz-Stefan Gady|work=The Diplomat|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-US}}</ref> 10% in the UK,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2017|title=UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2017|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|website=www.gov.uk|language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> 13% in Sweden,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/om-myndigheten/vara-varderingar/jamstalldhet-och-jamlikhet/historik/|title=Historik|last=Försvarsmakten|website=Försvarsmakten|language=sv-SE|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> 16% in the US,<ref name=":12">{{Cite web|url=http://www.usarec.army.mil/support/faqs.htm|title=Support Army Recruiting|last=US Army|date=2013|website=www.usarec.army.mil|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> and 27% in South Africa.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=16708:fact-file-sandf-regular-force-levels-by-race-a-gender-april-30-2011-&catid=79:fact-files&Itemid=159|title=Fact file: SANDF regular force levels by race & gender: April 30, 2011 {{!}} defenceWeb|last=Engelbrecht|first=Leon|website=www.defenceweb.co.za|language=en-gb|access-date=2017-12-11|date=2011-06-29}}</ref> |

Across the world, a large majority of recruits to state [[armed forces]] and [[Violent non-state actor|non-state armed groups]] are male. The proportion of female personnel varies internationally; for example, it is approximately 3% in India,<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://thediplomat.com/2016/02/indias-military-to-allow-women-in-combat-roles/|title=India's Military to Allow Women in Combat Roles|last=Franz-Stefan Gady|work=The Diplomat|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-US}}</ref> 10% in the UK,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2017|title=UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2017|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|website=www.gov.uk|date=30 November 2017 |language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> 13% in Sweden,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/om-myndigheten/vara-varderingar/jamstalldhet-och-jamlikhet/historik/|title=Historik|last=Försvarsmakten|website=Försvarsmakten|language=sv-SE|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> 16% in the US,<ref name=":12">{{Cite web|url=http://www.usarec.army.mil/support/faqs.htm|title=Support Army Recruiting|last=US Army|date=2013|website=www.usarec.army.mil|access-date=2017-12-11|archive-date=2018-11-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181109101909/http://www.usarec.army.mil/support/faqs.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> and 27% in South Africa.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=16708:fact-file-sandf-regular-force-levels-by-race-a-gender-april-30-2011-&catid=79:fact-files&Itemid=159|title=Fact file: SANDF regular force levels by race & gender: April 30, 2011 {{!}} defenceWeb|last=Engelbrecht|first=Leon|website=www.defenceweb.co.za|language=en-gb|access-date=2017-12-11|date=2011-06-29}}</ref> |

||

While many states do not recruit women for ground close [[combat]] roles (i.e. roles which would require them to kill an opponent at [[Close quarters combat|close quarters]]), several have lifted this ban in recent years, including larger [[Western world|Western military powers]] such as France, the UK, and US.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2013/01/25/map-which-countries-allow-women-in-front-line-combat-roles/|title=Map: Which countries allow women in front-line combat roles?|last=Fisher|first=Max|date=2013-01-25| |

While many states do not recruit women for ground close [[combat]] roles (i.e. roles which would require them to kill an opponent at [[Close quarters combat|close quarters]]), several have lifted this ban in recent years, including larger [[Western world|Western military powers]] such as France, the UK, and US.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2013/01/25/map-which-countries-allow-women-in-front-line-combat-roles/|title=Map: Which countries allow women in front-line combat roles?|last=Fisher|first=Max|date=2013-01-25|newspaper=Washington Post|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-US|issn=0190-8286}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ban-on-women-in-ground-close-combat-roles-lifted|title=Ban on women in ground close combat roles lifted|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|website=www.gov.uk|language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref> |

||

Compared with male personnel and female civilians, female personnel face substantially higher risks of [[Sexual harassment in the military|sexual harassment]] and [[Military sexual trauma (United States armed forces)|sexual violence]], according to British, Canadian, and US research.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446224/ADR005000-Sexual_Harassment_Report.pdf|title=British Army: Sexual Harassment Report|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2015|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-603-x/85-603-x2016001-eng.htm|title=Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016|last=Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency]|date=2016|website=www.statcan.gc.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref name="Marshall 862–876">{{Cite journal|last1=Marshall|first1=A|last2=Panuzio|first2=J|last3=Taft|first3=C|title=Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen|journal=Clinical Psychology Review|language=en|volume=25|issue=7|pages=862–876|doi=10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009|pmid=16006025|year=2005}}</ref> |

Compared with male personnel and female civilians, female personnel face substantially higher risks of [[Sexual harassment in the military|sexual harassment]] and [[Military sexual trauma (United States armed forces)|sexual violence]], according to British, Canadian, and US research.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446224/ADR005000-Sexual_Harassment_Report.pdf|title=British Army: Sexual Harassment Report|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2015|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-603-x/85-603-x2016001-eng.htm|title=Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016|last=Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency]|date=2016|website=www.statcan.gc.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref name="Marshall 862–876">{{Cite journal|last1=Marshall|first1=A|last2=Panuzio|first2=J|last3=Taft|first3=C|title=Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen|journal=Clinical Psychology Review|language=en|volume=25|issue=7|pages=862–876|doi=10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009|pmid=16006025|year=2005}}</ref> |

||

Some states, including the UK, US and Canada have begun to recognise a right of [[Transgender|transgender people]] to serve openly in their armed forces, although this development has met with political and cultural resistance.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/11/us/politics/transgender-military-pentagon.html|title=Transgender People Will Be Allowed to Enlist in the Military as a Court Case Advances|last=Cooper|first=Helene|date=2017-12-11|work=The New York Times|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-40733701|title=UK top brass back transgender troops|date=2017-07-26|work=BBC News|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/military-transgender-caf-policy-1.4978669|title=Canada's military issues new policies to welcome transgender troops as Trump insists on ban}}</ref> |

Some states, including the UK, US and Canada have begun to recognise a right of [[Transgender|transgender people]] to serve openly in their armed forces, although this development has met with political and cultural resistance.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/11/us/politics/transgender-military-pentagon.html|title=Transgender People Will Be Allowed to Enlist in the Military as a Court Case Advances|last=Cooper|first=Helene|date=2017-12-11|work=The New York Times|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-40733701|title=UK top brass back transgender troops|date=2017-07-26|work=BBC News|access-date=2017-12-11|language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/military-transgender-caf-policy-1.4978669|title=Canada's military issues new policies to welcome transgender troops as Trump insists on ban}}</ref> |

||

=== Age === |

=== Age group === |

||

State armed forces set minimum and maximum ages for recruitment. In practice, most military recruits are young adults; for example, in 2013 the average age of a [[United States Army]] soldier beginning [[Recruit training|initial training]] was 20.7 years.<ref name=":12" /> |

State armed forces set minimum and maximum ages for recruitment. In practice, most military recruits are young adults; for example, in 2013 the average age of a [[United States Army]] soldier beginning [[Recruit training|initial training]] was 20.7 years.<ref name=":12" /> |

||

==== Child recruitment ==== |

==== Child recruitment ==== |

||

{{Main|Children in the military}}Under the [[Convention on the Rights of the Child]], a child means a person aged under 18. |

{{Main|Children in the military}} |

||

Under the [[Convention on the Rights of the Child]], a child means a person aged under 18. |

|||

The minimum age at which children may be recruited or conscripted under the [[Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court]] is 15.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/ea9aeff7-5752-4f84-be94-0a655eb30e16/0/rome_statute_english.pdf|title=Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (A/CONF.183/9)|date=1998|access-date=2018-03-22}}</ref> States which have ratified the [[Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict|Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict]] (OPAC) may not conscript children at all, but may enlist children aged 16 or above provided that they are not used to participate directly in hostilities.<ref name=":16">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPACCRC.aspx|title=Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict|date=2000|website=www.ohchr.org|language=en-US|access-date=2018-03-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130502015246/http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPACCRC.aspx|archive-date=2013-05-02|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

The minimum age at which children may be recruited or conscripted under the [[Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court]] is 15.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/ea9aeff7-5752-4f84-be94-0a655eb30e16/0/rome_statute_english.pdf|title=Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (A/CONF.183/9)|date=1998|access-date=2018-03-22}}</ref> States which have ratified the [[Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict|Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict]] (OPAC) may not conscript children at all, but may enlist children aged 16 or above provided that they are not used to participate directly in hostilities.<ref name=":16">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPACCRC.aspx|title=Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict|date=2000|website=www.ohchr.org|language=en-US|access-date=2018-03-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130502015246/http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPACCRC.aspx|archive-date=2013-05-02|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

| Line 37: | Line 38: | ||

=== Socio-economic background === |

=== Socio-economic background === |

||

The hope of escaping [[Socio-economic gap|socio-economic deprivation]] is one of the main |

The hope of escaping [[Socio-economic gap|socio-economic deprivation]] is one of the main factors attracting young people to military employment.<ref name=":02"/><ref name=":62">{{Cite web|url= https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_49985.html|title= Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review: Children and conflict in a changing world|website= UNICEF|access-date= 2017-12-08|archive-date= 2017-12-09|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20171209100213/https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_49985.html|url-status= dead}}</ref> (Thus the obsolete English-language term "bezonian" may mean "raw recruit" or "pauper".<ref>{{oed | bezonian}}</ref>) After the US suspended conscription in 1973, "the military disproportionately attracted African American men, men from lower-status socioeconomic backgrounds, men who had been in nonacademic high school programs, and men whose high school grades tended to be low".<ref name=":42">{{Cite journal|last=Segal, D R|display-authors=etal|date=1998|title=The all-volunteer force in the 1970s|jstor= 42863796|journal= Social Science Quarterly|volume= 72 |issue= 2|pages= 390–411}}</ref> However, a 2020 study suggests that the socio-economic status of [[United States Armed Forces|U.S. Armed Forces]] personnel is at parity with or slightly higher than the civilian population and that the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups are less likely to meet the requirements of the modern U.S. military. A study found that technological, tactical, operational and doctrinal changes have led to a change in the demand for personnel.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1= Asoni|first1= Andrea|last2= Gilli |first2= Andrea|last3= Gilli|first3= Mauro|last4= Sanandaji|first4= Tino|date= 2020-01-30|title= A mercenary army of the poor? Technological change and the demographic composition of the post-9/11 U.S. military|journal=Journal of Strategic Studies|volume= 45|issue= 4|pages=568–614|doi=10.1080/01402390.2019.1692660|issn=0140-2390|doi-access=}}</ref> As an indication of the socio-economic background of [[British Army]] personnel, {{as of | 2015 | lc = on}} three-quarters of its youngest recruits had the [[literacy]] skills normally expected of an 11-year-old or younger, and 7% had a reading age of 5–7.<ref name=":102">{{Cite journal|last1= Gee|first1= David|last2= Taylor|first2= Rachel|date= 2016-11-01|title= Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army?|journal=The RUSI Journal|volume=161|issue=6|pages=36–48|doi= 10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837|s2cid=157986637|issn=0307-1847}}</ref> The British Army's recruitment drive in 2017 targeted working-class families with an average annual income of £10,000.<ref name="Morris">{{Cite news|url= https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/09/british-army-is-targeting-working-class-young-people-report-shows |title= British army is targeting working-class young people, report shows|last= Morris|first= Steven|date= 2017-07-09|work=The Guardian|access-date=2017-12-08|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> |

||

Recruitment for [[Officer (armed forces)|officers]] typically draws on [[Upwardly mobile|upwardly-mobile]] young adults from age 18, and recruiters for these roles focus their resources on high-achieving schools and universities.<ref name=":42"/><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Bachman|first1=Jerald G.|last2=Segal|first2=David R.|last3=Freedman-Doan|first3=Peter|last4=O'Malley|first4=Patrick M.|title=Who chooses military service? Correlates of propensity and enlistment in the U.S. Armed Forces |

Recruitment for [[Officer (armed forces)|officers]] typically draws on [[Upwardly mobile|upwardly-mobile]] young adults from age 18, and recruiters for these roles focus their resources on high-achieving schools and universities.<ref name=":42"/><ref>{{Cite journal|last1= Bachman|first1= Jerald G.|last2= Segal|first2= David R.|last3= Freedman-Doan|first3= Peter|last4= O'Malley|first4= Patrick M.|title= Who chooses military service? Correlates of propensity and enlistment in the U.S. Armed Forces |journal= Military Psychology|language= en|volume= 12|issue= 1|pages= 1–30|doi= 10.1207/s15327876mp1201_1|year=2000|s2cid=143845150}}</ref> (Canada is an exception, recruiting high-achieving children from age 16 for officer training.<ref> |

||

{{Cite web|url=http://www.cmrsj-rmcsj.forces.gc.ca/fe-fs/adm/adm-eng.asp|title=Admission - Futurs Students - Royal Military College Saint-Jean|last=Saint-Jean|first= Departement of National Defence, Chief Military Personnel, Canadian Defence Academy, Royal Military College |website= www.cmrsj-rmcsj.forces.gc.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-08|date=2015-05-12}} |

|||

</ref>) |

|||

== Outreach and marketing == |

== Outreach and marketing == |

||

=== Early years === |

=== Early years === |

||

The process of attracting children and young people to military employment begins in their early years. In Germany, Israel, Poland, the UK, the US, and elsewhere, the armed forces visit schools frequently, including primary schools, to encourage children to enlist once they become old enough to do so.<ref name=":92">{{Cite book|title=Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany|last=Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns|year=2016}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=Adela|title=Teaching war|date=2016-11-03|url=https://vimeo.com/190069406|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref name="New Profile 2004">{{Cite web|url=https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://new.newprofile.org/sites/default/files/infokits/english.pdf|title=The New Profile Report on Child Recruitment in Israel|last=New Profile|date=2004|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web| |

The process of attracting children and young people to military employment begins in their early years. In Germany, Israel, Poland, the UK, the US, and elsewhere, the armed forces visit schools frequently, including primary schools, to encourage children to enlist once they become old enough to do so.<ref name=":92">{{Cite book|title=Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany|last=Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns|year=2016}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=Adela|title=Teaching war|date=2016-11-03|url=https://vimeo.com/190069406|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref name="New Profile 2004">{{Cite web|url=https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://new.newprofile.org/sites/default/files/infokits/english.pdf|title=The New Profile Report on Child Recruitment in Israel|last=New Profile|date=2004|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref name=":22">{{Cite web |author1=Gee, D |author2=Goodman, A |title=Army visits London's poorest schools most often |url=http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180529080003/http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |archive-date=2018-05-29 |access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Hagopian|first1=Amy|last2=Barker|first2=Kathy|date=2011|title=Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health?|journal=American Journal of Public Health|volume=101|issue=1|pages=19–23|doi=10.2105/AJPH.2009.183418|issn=0090-0036|pmc=3000735|pmid=21088269}}</ref><ref name=":10">{{Cite web|url=http://www.usarec.army.mil/im/formpub/rec_pubs/man3_01.pdf|title=Recruiter Handbook|last=US Army|access-date=2017-12-10|archive-date=2018-02-19|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180219031556/http://www.usarec.army.mil/im/formpub/rec_pubs/man3_01.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite web|url=https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ110/html/PLAW-107publ110.htm|title=No Child Left Behind Act (2001) (Section 9528)|last=US Government|date=2001|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> For example, a poster used by the [[Bundeswehr|German armed forces]] in schools reads: "After school you have the world at your feet, make it safer." ["''Nach der Schule liegt dir die Welt zu Füßen, mach sie sicherer''."]<ref name=":92"/> In the US, recruiters have right of access to all schools and to the contact details of students,<ref name=":11" /> and are encouraged to embed themselves into the school community.<ref name=":10" /> A former head of recruitment for the [[British Army]], Colonel (latterly Brigadier) David Allfrey, explained the British approach in 2007:<blockquote>Our new model is about raising awareness, and that takes a ten-year span. It starts with a seven-year-old boy seeing a [[Parachuting|parachutist]] at an [[air show]] and thinking, 'That looks great.' From then the army is trying to build interest by drip, drip, drip.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2007/02/british-army-recruitment-iraq|title=Britain's child army|last=Armstrong|first=S|website=www.newstatesman.com|language=en|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref></blockquote> |

||

=== Popular culture === |

=== Popular culture === |

||

Recruiters use [[action film]]s and [[Video game|videogames]] to promote military employment. Scenes from [[Hollywood blockbuster]]s (including ''[[Behind Enemy Lines (2001 film)|Behind Enemy Lines]]'' and ''[[X-Men: First Class]]'')<ref>{{Citation|last=BreezyVideos2|title=X-Men: First Class: TV Spot - Go Army (HD)|date=2011-05-20|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-OvnGgfwQc|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=jsmmusic|title=U.S Navy "Behind Enemy Lines"|date=2015-01-15|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5N7hnjPnZFI|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> have been spliced into military advertising in the US, for example. In the US and elsewhere, the armed forces commission [[bespoke]] videogames to present military life to children and have created the [[U.S. Army Esports]] initiative as an outreach program using [[esports]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.goarmy.com/downloads/games.html|title=Go Army|last=US Army|website=goarmy.com|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=2018-11-23|title='The US military is using video games and esports to recruit – it's downright immoral'|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/army-military-video-game-fortnite-battlegrounds-call-duty-esports-defence-a8648656.html|access-date=2020-07-24|website=The Independent|language=en}}</ref> |

Recruiters use [[action film]]s and [[Video game|videogames]] to promote military employment. Scenes from [[Hollywood blockbuster]]s (including ''[[Behind Enemy Lines (2001 film)|Behind Enemy Lines]]'' and ''[[X-Men: First Class]]'')<ref>{{Citation|last=BreezyVideos2|title=X-Men: First Class: TV Spot - Go Army (HD)|date=2011-05-20|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-OvnGgfwQc|access-date=2017-12-10}}{{cbignore}}{{Dead Youtube links|date=February 2022}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=jsmmusic|title=U.S Navy "Behind Enemy Lines"|date=2015-01-15|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5N7hnjPnZFI|access-date=2017-12-10}}{{cbignore}}{{Dead Youtube links|date=February 2022}}</ref> have been spliced into military advertising in the US, for example. In the US and elsewhere, the armed forces commission [[bespoke]] videogames to present military life to children and have created the [[U.S. Army Esports]] initiative as an outreach program using [[esports]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.goarmy.com/downloads/games.html|title=Go Army|last=US Army|website=goarmy.com|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=2018-11-23|title='The US military is using video games and esports to recruit – it's downright immoral'|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/army-military-video-game-fortnite-battlegrounds-call-duty-esports-defence-a8648656.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220514/https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/army-military-video-game-fortnite-battlegrounds-call-duty-esports-defence-a8648656.html |archive-date=2022-05-14 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|access-date=2020-07-24|website=The Independent|language=en}}</ref> |

||

=== Military schools and youth organisations === |

=== Military schools and youth organisations === |

||

Many states operate military schools, cadet forces, and other military youth organisations. For example, Russia operates a system of military schools for children from age 10, where [[combat]] skills and [[Weapons Training|weapons training]] are taught as part of the curriculum.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC/C/OPAC/RUS/CO/1&Lang=en|title=Concluding observations on the report submitted by the Russian Federation under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict|last=Committee on the Rights of the Child|date=2014|website=tbinternet.ohchr.org|language=en-us|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> The UK is one of many states that subsidise participation in [[Army Cadet Force|cadet forces]], where children from age 12 play out a stylised representation of military employment.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://armycadets.com/join-cadets/|title=Join the Army Cadets|last=UK, Army Cadet Force|website=armycadets.com|language=en|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> |

Many states operate military schools, cadet forces, and other military youth organisations. For example, Russia operates a system of military schools for children from age 10, where [[combat]] skills and [[Weapons Training|weapons training]] are taught as part of the curriculum.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC/C/OPAC/RUS/CO/1&Lang=en|title=Concluding observations on the report submitted by the Russian Federation under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict|last=Committee on the Rights of the Child|date=2014|website=tbinternet.ohchr.org|language=en-us|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> The UK is one of many states that subsidise participation in [[Army Cadet Force|cadet forces]], where children from age 12 play out a stylised representation of military employment.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://armycadets.com/join-cadets/|title=Join the Army Cadets|last=UK, Army Cadet Force|website=armycadets.com|language=en|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> The United States offers [[Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps]] to high school students as an extracurricular activity. |

||

=== Advertising === |

=== Advertising === |

||

Armed forces commission recruitment advertising across a wide range of media, including television,<ref>{{Citation|last=sairagon1988|title=Russian Army Commercial|date=2011-11-11|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYxeGb3pXzk|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> radio,<ref>{{Citation|last=Radio Ads 24|title=British Army Radio Advert #1 (30 Seconds)|date=2017-09-03|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ib-Q-QWA_Y0|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> cinema,<ref>{{Citation|last=adsoftheworldvideos|title=Royal Navy: Made in the Royal Navy - Born in Carslile|date=2014-12-27|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12WqvFPulqw|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> online including social media,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://twitter.com/armeedeterre?lang=en|title=Armée de Terre (@armeedeterre) {{!}} Twitter|website=twitter.com|language=en|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> the press, billboards,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://porteradsblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/air-force.jpg|title=US Air Force billboard [image]|last=US Air Force|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> brochures and leaflets,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.army.mod.uk/documents/general/Meet_The_Army.pdf|title=Meet the army: A guide for parents, partners and friends|last=British Army|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140903011549/http://army.mod.uk/documents/general/Meet_The_Army.pdf|archive-date=2014-09-03|url-status=dead|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> and through [[merchandising]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.amazon.co.uk/Toys-Games-HM-Armed-Forces/s?ie=UTF8&page=1&rh=n:468292,p_n_featured_character_browse-bin:368014031|title=Amazon.co.uk: HM Armed Forces: Toys & Games|website=www.amazon.co.uk|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> |

Armed forces commission recruitment advertising across a wide range of media, including television,<ref>{{Citation|last=sairagon1988|title=Russian Army Commercial|date=2011-11-11|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYxeGb3pXzk |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/tYxeGb3pXzk |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|access-date=2017-12-10}}{{cbignore}}</ref> radio,<ref>{{Citation|last=Radio Ads 24|title=British Army Radio Advert #1 (30 Seconds)|date=2017-09-03|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ib-Q-QWA_Y0 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/Ib-Q-QWA_Y0 |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|access-date=2017-12-10}}{{cbignore}}</ref> cinema,<ref>{{Citation|last=adsoftheworldvideos|title=Royal Navy: Made in the Royal Navy - Born in Carslile|date=2014-12-27|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12WqvFPulqw |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/12WqvFPulqw |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|access-date=2017-12-10}}{{cbignore}}</ref> online including social media,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://twitter.com/armeedeterre?lang=en|title=Armée de Terre (@armeedeterre) {{!}} Twitter|website=twitter.com|language=en|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> the press, billboards,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://porteradsblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/air-force.jpg|title=US Air Force billboard [image]|last=US Air Force|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> brochures and leaflets,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.army.mod.uk/documents/general/Meet_The_Army.pdf|title=Meet the army: A guide for parents, partners and friends|last=British Army|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140903011549/http://army.mod.uk/documents/general/Meet_The_Army.pdf|archive-date=2014-09-03|url-status=dead|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> [[Employment website]]s and through [[merchandising]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.amazon.co.uk/Toys-Games-HM-Armed-Forces/s?ie=UTF8&page=1&rh=n:468292,p_n_featured_character_browse-bin:368014031|title=Amazon.co.uk: HM Armed Forces: Toys & Games|website=www.amazon.co.uk|access-date=2017-12-10}}</ref> |

||

=== Public realm === |

=== Public realm === |

||

| Line 59: | Line 62: | ||

== Messaging == |

== Messaging == |

||

Recruitment marketing seeks to appeal to potential recruits in the following ways: |

Recruitment marketing seeks to appeal to potential recruits in the following ways: |

||

* '''Traditionally masculine associations.''' Historically and today, recruitment materials frequently associate military life with that of a traditionally [[Masculinity|masculine]] [[warrior]], which is officially encouraged as a martial ideal.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.defence.gov.au/publications/docs/LCIreport.pdf|title=Final report of the Learning Culture Inquiry|last=Australia, Department of Defence|date=2006|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605298/Army_Field_Manual__AFM__A5_Master_ADP_Interactive_Gov_Web.pdf|title=Army Doctrine Publications: Operations|last=UK, British Army|date=2010|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.army.mil/values/warrior.html|title=Warrior Ethos - Army Values|last=US Army|website=www.army.mil|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> For example, [[Cold War]] [[United States Army|US Army]] [[slogan]]s included "Join the army, Be a man" and "The army will make a man out of you";<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Arkin|first1=William|last2=Dobrofsky|first2=Lynne R.|date=1978-01-01|title=Military Socialization and Masculinity|journal=Journal of Social Issues|language=en|volume=34|issue=1|pages=151–168|doi=10.1111/j.1540-4560.1978.tb02546.x|issn=1540-4560}}</ref> in 2007 a new slogan was introduced: " |

* '''Traditionally masculine associations.''' Historically and today, recruitment materials frequently associate military life with that of a traditionally [[Masculinity|masculine]] [[warrior]], which is officially encouraged as a martial ideal.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.defence.gov.au/publications/docs/LCIreport.pdf|title=Final report of the Learning Culture Inquiry|last=Australia, Department of Defence|date=2006|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605298/Army_Field_Manual__AFM__A5_Master_ADP_Interactive_Gov_Web.pdf|title=Army Doctrine Publications: Operations|last=UK, British Army|date=2010|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.army.mil/values/warrior.html|title=Warrior Ethos - Army Values|last=US Army|website=www.army.mil|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> For example, [[Cold War]] [[United States Army|US Army]] [[slogan]]s included "Join the army, Be a man" and "The army will make a man out of you";<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Arkin|first1=William|last2=Dobrofsky|first2=Lynne R.|date=1978-01-01|title=Military Socialization and Masculinity|journal=Journal of Social Issues|language=en|volume=34|issue=1|pages=151–168|doi=10.1111/j.1540-4560.1978.tb02546.x|issn=1540-4560}}</ref> in 2007 a new slogan was introduced: "There's strong. Then there's army strong".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.army.mil/aps/08/information_papers/sustain/Army_Strong.html|title=2008 U.S. Army Posture Statement - Information Papers - Army Strong: New Army Recruiting Campaign|last=US Army|date=2007|website=www.army.mil|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> Similarly, recruiters describe the Israeli infantryman as "discovering all your strengths";<ref name="shaharTV">{{Citation|last=shaharTV|title=IDF Commercial|date=2011-06-17|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxrlwG8_LIo |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/kxrlwG8_LIo |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|access-date=2017-12-13}}{{cbignore}}</ref> and the British is "harder, faster, fitter, stronger".<ref>{{Cite book|title=Army Life: Your Guide to the Infantry|last=UK, Army Recruiting and Training Division|publisher=UK, Ministry of Defence|year=2013}}</ref> |

||

* '''Teamwork and belonging.''' Some armed forces appeal to potential recruits with the promise of teamwork and camaraderie. An example is the [[British Army]], which introduced the slogan "This is belonging" in 2017.<ref name=":14">{{Cite web|url=https://apply.army.mod.uk/|title=British Army Jobs - Apply Online|last=UK, British Army|date=2017|website=apply.army.mod.uk|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> |

* '''Teamwork and belonging.''' Some armed forces appeal to potential recruits with the promise of teamwork and camaraderie. An example is the [[British Army]], which introduced the slogan "This is belonging" in 2017.<ref name=":14">{{Cite web|url=https://apply.army.mod.uk/|title=British Army Jobs - Apply Online|last=UK, British Army|date=2017|website=apply.army.mod.uk|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> |

||

* '''Patriotic service.''' Some armed forces present military life as a patriotic service. For example, the slogan for the German ''[[Bundeswehr]]'' is "We. Serve. Germany." ["Wir. Dienen. Deutschland."], and an advertisement for the [[Israel Defense Forces|Israeli Defense Forces]] encourages potential recruits to "Above all, fight [''kravi''] for your country, because there is no place better than Israel."<ref name="shaharTV"/> |

* '''Patriotic service.''' Some armed forces present military life as a patriotic service. For example, the slogan for the German ''[[Bundeswehr]]'' is "We. Serve. Germany." ["Wir. Dienen. Deutschland."], and an advertisement for the [[Israel Defense Forces|Israeli Defense Forces]] encourages potential recruits to "Above all, fight [''kravi''] for your country, because there is no place better than Israel."<ref name="shaharTV"/> |

||

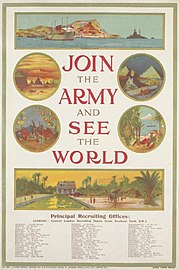

* '''Challenge and adventure.''' Military life is promised to be exciting, including world travel and adventurous training. In 2015, the [[British Army]] presentation to schools included prominent images of scuba diving and snowboarding, for example.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/army-presentation-schools|title=Army presentation for schools|last=UK, British Army|date=2015|website=www.forceswatch.net|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> |

* '''Challenge and adventure.''' Military life is promised to be exciting, including world travel and adventurous training. In 2015, the [[British Army]] presentation to schools included prominent images of scuba diving and snowboarding, for example.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/army-presentation-schools|title=Army presentation for schools|last=UK, British Army|date=2015|website=www.forceswatch.net|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> |

||

* '''Education and skills.''' The armed forces are often presented as a means to learn new skills.<ref name=":15">{{Citation|last=A. Enderborgesas|title=Swedish Recruitment Ad "Welcome to Our Reality"|date=2011-04-08|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AprqomTW-Wo|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref name=":14" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/caf-jobs/education-benefits.html|title=Paid education and other benefits|last=Canada, National Defence|website=www.canada.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> For example, the Swedish armed forces encourage potential recruits with the promise of "education that leads to a job where you can make a difference".<ref name=":15" /> |

* '''Education and skills.''' The armed forces are often presented as a means to learn new skills.<ref name=":15">{{Citation|last=A. Enderborgesas|title=Swedish Recruitment Ad "Welcome to Our Reality"|date=2011-04-08|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AprqomTW-Wo |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211221/AprqomTW-Wo |archive-date=2021-12-21 |url-status=live|access-date=2017-12-13}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name=":14" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/caf-jobs/education-benefits.html|title=Paid education and other benefits|last=Canada, National Defence|website=www.canada.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref> For example, the Swedish armed forces encourage potential recruits with the promise of "education that leads to a job where you can make a difference".<ref name=":15" /> |

||

== Application process == |

== Application process == |

||

Typically, candidates for military employment apply online or at a recruitment centre. |

Typically, candidates for military employment apply online or at a recruitment centre. |

||

Many eligibility criteria normally apply, which may be related to age, nationality, height and weight ([[body mass index]]), [[medical history]], [[Psychiatry|psychiatric]] history, illicit [[ |

Many eligibility criteria normally apply, which may be related to age, nationality, height and weight ([[body mass index]]), [[medical history]], [[Psychiatry|psychiatric]] history, illicit [[Substance abuse|drug use]], [[criminal record]], [[Academic achievement|academic results]], [[Identity document|proof of identity]], satisfactory references, and whether any [[tattoo]]s are visible. A minimum standard of academic attainment may be required for entry, for certain technical roles, or for entry to train for a leadership position as a [[Officer (armed forces)|commissioned officer]]. Candidates who meet the criteria will normally also undergo [[Aptitude|aptitude test]], [[medical examination]], psychological interview, job interview and fitness assessment. |

||

Depending on whether the application criteria are met, and depending also on which military units have vacancies for new recruits, candidates may or may not be offered a job in a certain role or roles. Candidates who accept a job offer then wait for their [[recruit training]] to begin. Either at or before the start of their training, candidates swear or affirm an [[oath of allegiance]] and/or sign their joining papers. |

Depending on whether the application criteria are met, and depending also on which military units have vacancies for new recruits, candidates may or may not be offered a job in a certain role or roles. Candidates who accept a job offer then wait for their [[recruit training]] to begin. Either at or before the start of their training, candidates swear or affirm an [[oath of allegiance]] and/or sign their joining papers. |

||

| Line 80: | Line 83: | ||

== Terms of service == |

== Terms of service == |

||

{{Main|Military personnel}} |

{{Main|Military personnel}} |

||

Recruits enter a binding [[contract]] of service, which for full-time personnel typically requires a minimum period of service of several years,<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=|title=Army - Artillery - Air Defender|url=https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/jobs/army/air-defence-operator| |

Recruits enter a binding [[contract]] of service, which for full-time personnel typically requires a minimum period of service of several years,<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=|title=Army - Artillery - Air Defender|url=https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/jobs/army/air-defence-operator|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180319164323/https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/jobs/Army/air-defence-operator|url-status=dead|archive-date=March 19, 2018|access-date=2017-12-09|website=army.defencejobs.gov.au|language=en}}</ref><ref name=":102"/><ref name=":6">{{Cite news|url=http://military.findlaw.com/administrative-issues-benefits/what-is-a-military-enlistment-contract.html|title=What is a Military Enlistment Contract?|work=Findlaw|access-date=2017-12-09}}</ref> with the exception of a short [[Military discharge|discharge]] window, near the beginning of their service, allowing them to leave the armed force as of right.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web|url=https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/3382/contents/made|title=The Army Terms of Service Regulations 2007|website=www.legislation.gov.uk|language=en|access-date=2017-12-09}}</ref> Part-time military employment, known as [[Military reserve force|reserve service]], allows a recruit to maintain a civilian job while training under military discipline for a minimum number of days per year. After leaving the armed forces, for a fixed period (between four and six years is normal in the UK and US, for example<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6" />), former recruits may remain liable for compulsory return to full-time military employment in order to train or [[Military operation|deploy on operations]]. |

||

From the point of their enlistment/commissioning, personnel become subject to [[Military Law|military law]], which introduces offences not recognised by civilian courts, such as disobedience. Penalties range from a summary [[reprimand]] to imprisonment for several years following a [[Court-martial|court martial]].<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440632/20150529-QR_Army_Amdt_31_Jul_2013.pdf|title=Queen's Regulations for the Army (1975, as amended)|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2017|access-date=2017-12-09}}</ref> |

From the point of their enlistment/commissioning, personnel become subject to [[Military Law|military law]], which introduces offences not recognised by civilian courts, such as disobedience. Penalties range from a summary [[reprimand]] to imprisonment for several years following a [[Court-martial|court martial]].<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440632/20150529-QR_Army_Amdt_31_Jul_2013.pdf|title=Queen's Regulations for the Army (1975, as amended)|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2017|access-date=2017-12-09}}</ref> |

||

| Line 90: | Line 93: | ||

== Counter-recruitment == |

== Counter-recruitment == |

||

{{Main|Counter-recruitment}} |

{{Main|Counter-recruitment}} |

||

{{Excessive citations|section|date=April 2021}} |

|||

Counter-recruitment refers to activity opposing military recruitment, or aspects of it. Among its forms are [[Advocacy|political advocacy]], [[Consciousness raising|consciousness-raising]], and [[direct action]]. The rationale for counter-recruitment activity may be based on any of the following reasons: |

Counter-recruitment refers to activity opposing military recruitment, or aspects of it. Among its forms are [[Advocacy|political advocacy]], [[Consciousness raising|consciousness-raising]], and [[direct action]]. The rationale for counter-recruitment activity may be based on any of the following reasons: |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* The view that war is immoral - see [[pacifism]]. |

|||

* Evidence that [[bullying]], [[harassment]] and [[sexual violence]] are more common in military organizations than elsewhere<ref name=":13">{{Cite web|url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom|title=Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom|last=Gee|first=D|date=2008|access-date=2017-12-13|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171213204740/https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom|archive-date=2017-12-13|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446224/ADR005000-Sexual_Harassment_Report.pdf|title=British Army: Sexual Harassment Report|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2015|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-603-x/85-603-x2016001-eng.htm|title=Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016|last=Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency]|date=2016|website=www.statcan.gc.ca|language=en|access-date=2017-12-11}}</ref><ref name="Marshall 862–876"/> (see, for example, [[Women in the military]] and [[Sexual orientation and gender identity in military service]]). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* Evidence that military training and employment lead to higher rates of mental health and behavioural problems than are usually found in civilian life, particularly after personnel have left the armed forces.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Hoge|first1=Charles W.|last2=Castro|first2=Carl A.|last3=Messer|first3=Stephen C.|last4=McGurk|first4=Dennis|last5=Cotting|first5=Dave I.|last6=Koffman|first6=Robert L.|date=2004-07-01|title=Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|volume=351|issue=1|pages=13–22|doi=10.1056/nejmoa040603|issn=0028-4793|pmid=15229303|citeseerx=10.1.1.376.5881}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=MacManus|first1=Deirdre|last2=Rona|first2=Roberto|last3=Dickson|first3=Hannah|last4=Somaini|first4=Greta|last5=Fear|first5=Nicola|last6=Wessely|first6=Simon|date=2015-01-01|title=Aggressive and Violent Behavior Among Military Personnel Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: Prevalence and Link With Deployment and Combat Exposure|journal=Epidemiologic Reviews|volume=37|issue=1|pages=196–212|doi=10.1093/epirev/mxu006|pmid=25613552|issn=0193-936X|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Goodwin|first1=L.|last2=Wessely|first2=S.|last3=Hotopf|first3=M.|last4=Jones|first4=M.|last5=Greenberg|first5=N.|last6=Rona|first6=R. J.|last7=Hull|first7=L.|last8=Fear|first8=N. T.|date=2015|title=Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population?|journal=Psychological Medicine|volume=45|issue=9|pages=1881–1891|doi=10.1017/s0033291714002980|pmid=25602942|s2cid=3026974|issn=0033-2917}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=MacManus|first1=Deirdre|last2=Dean|first2=Kimberlie|last3=Jones|first3=Margaret|last4=Rona|first4=Roberto J|last5=Greenberg|first5=Neil|last6=Hull|first6=Lisa|last7=Fahy|first7=Tom|last8=Wessely|first8=Simon|last9=Fear|first9=Nicola T|title=Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study|journal=The Lancet|language=en|volume=381|issue=9870|pages=907–917|doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60354-2|pmid=23499041|year=2013|s2cid=606331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Thandi|first1=Gursimran|last2=Sundin|first2=Josefin|last3=Ng-Knight|first3=Terry|last4=Jones|first4=Margaret|last5=Hull|first5=Lisa|last6=Jones|first6=Norman|last7=Greenberg|first7=Neil|last8=Rona|first8=Roberto J.|last9=Wessely|first9=Simon|title=Alcohol misuse in the United Kingdom Armed Forces: A longitudinal study|journal=Drug and Alcohol Dependence|language=en|volume=156|pages=78–83|doi=10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.033|pmid=26409753|year=2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Buckman|first1=Joshua E. J.|last2=Forbes|first2=Harriet J.|last3=Clayton|first3=Tim|last4=Jones|first4=Margaret|last5=Jones|first5=Norman|last6=Greenberg|first6=Neil|last7=Sundin|first7=Josefin|last8=Hull|first8=Lisa|last9=Wessely|first9=Simon|date=2013-06-01|title=Early Service leavers: a study of the factors associated with premature separation from the UK Armed Forces and the mental health of those that leave early|journal=European Journal of Public Health|volume=23|issue=3|pages=410–415|doi=10.1093/eurpub/cks042|pmid=22539627|issn=1101-1262|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Jones|first1=M.|last2=Sundin|first2=J.|last3=Goodwin|first3=L.|last4=Hull|first4=L.|last5=Fear|first5=N. T.|last6=Wessely|first6=S.|last7=Rona|first7=R. J.|date=2013|title=What explains post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in UK service personnel: deployment or something else?|journal=Psychological Medicine|volume=43|issue=8|pages=1703–1712|doi=10.1017/s0033291712002619|pmid=23199850|s2cid=21097249|issn=0033-2917}}</ref> |

|||

* Evidence from Australia, Canada, France, the UK, and the US that abusive behaviour such as [[bullying]], [[racism]], [[sexism]] and [[sexual violence]], and [[homophobia]] are common in military organizations.<ref name="abusesource2">* Australia: |

|||

* Evidence that recruiters capitalise on there being a lack of other career options for [[Economic inequality|socio-economically deprived]] young people,<ref name=":02"/><ref name=":62"/><ref name=":42"/><ref name="Morris"/><ref name=":13" /><ref name=":92"/><ref name=":22">{{Cite web|url=http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf|title=Army visits London's poorest schools most often|author1=Gee, D|author2=Goodman, A|access-date=2017-12-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180529080003/http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf|archive-date=2018-05-29|url-status=dead}}</ref> and obscure the risks of military employment.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Hagopian|first1=Amy|last2=Barker|first2=Kathy|date=2011-01-01|title=Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health?|journal=American Journal of Public Health|volume=101|issue=1|pages=19–23|doi=10.2105/ajph.2009.183418|pmid=21088269|issn=0090-0036|pmc=3000735}}</ref><ref name=":52">{{Cite web|url=https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/23/11/19/cessation-of-military-recruiting-in-public-elementary-and-secondary-schools|title=Cessation of Military Recruiting in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools|last=American Public Health Association|date=2012|website=www.apha.org|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.aclu.org/other/soldiers-misfortune-abusive-us-military-recruitment-and-failure-protect-child-soldiers|title=Soldiers of Misfortune: Abusive U.S. Military Recruitment and Failure to Protect Child Soldiers|work=American Civil Liberties Union|access-date=2017-12-13|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Diener, Sam|author2=Munro, Jamie|date=June–July 2005|title=Military Money for College: A Reality Check|url=http://www.peaceworkmagazine.org/pwork/0506/050607.htm|url-status=dead|journal=Peacework|publisher=[[American Friends Service Committee|AFSC]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061011153323/http://www.peaceworkmagazine.org/pwork/0506/050607.htm|archive-date=2006-10-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/05/20/national/main696991.shtml|title=Amid Scandal, Recruitment Halts|date=2005-05-20|publisher=CBS News}}</ref><ref name=":22" /><ref name=":13" /><ref name=":32">{{Cite web|url=http://vfpuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-First-Ambush-Effects-of-army-training-and-employment-WEB.pdf|title=The First Ambush? Effects of army training and employment|last=Gee|first=D|date=2017|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref name=":92" /><ref name="New Profile 2004"/> |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Defence Abuse Response Taskforce |date=2016 |title=Defence Abuse Response Taskforce: Final report |url=https://www.defenceabusetaskforce.gov.au/Reports/Documents/Dart-final-report-2016.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180313191521/https://www.defenceabusetaskforce.gov.au/Reports/Documents/Dart-final-report-2016.pdf |archive-date=2018-03-13 |access-date=2018-03-08}} |

|||

* The fact that some armed forces rely on children aged 16 or 17 to fill their ranks, and evidence that these youngest recruits are most likely to be adversely affected by the demands and risks of military life.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA427744|title=A review of the literature on attrition from the military services: Risk factors for attrition and strategies to reduce attrition|last=Knapik|display-authors=etal|date=2004|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref name=":32" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-suicide-and-open-verdict-deaths-2016|title=UK armed forces suicide and open verdict deaths: 2016|last=UK, Ministry of Defence|date=2017|website=www.gov.uk|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kapur|first1=Navneet|last2=While|first2=David|last3=Blatchley|first3=Nick|last4=Bray|first4=Isabelle|last5=Harrison|first5=Kate|date=2009-03-03|title=Suicide after Leaving the UK Armed Forces —A Cohort Study|journal=PLOS Medicine|volume=6|issue=3|pages=e1000026|doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000026|pmid=19260757|pmc=2650723|issn=1549-1676}}</ref><ref name=":72">{{Cite web|url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/young-age-army-enlistment-associated-greater-war-zone-risks-analysis-british-army-fataliti|title=Young age at Army enlistment is associated with greater war zone risks: An analysis of British Army fatalities in Afghanistan|last=Gee, D and Goodman, A|date=2013|website=www.forceswatch.net|language=en|access-date=2017-12-13}}</ref><ref name=":102"/> |

|||

* Canada: |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency] |date=2016 |title=Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016 |url=http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-603-x/85-603-x2016001-eng.htm |access-date=2017-12-11 |website=www.statcan.gc.ca |language=en}} |

|||

* France: |

|||

** {{Cite book |last1=Leila |first1=Miñano |title=La guerre invisible: révélations sur les violences sexuelles dans l'armée française |last2=Pascual |first2=Julia |publisher=Les Arènes |year=2014 |isbn=978-2352043027 |location=Paris |language=fr |oclc=871236655}} |

|||

** {{Cite news |last=Lichfield |first=John |date=2014-04-20 |title=France battles sexual abuse in the military |language=en-GB |work=Independent |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/france-battles-sexual-abuse-in-the-military-9271383.html |access-date=2018-03-08}} |

|||

* UK: |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee |first=D |date=2008 |title=Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom |url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171213204740/https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |archive-date=2017-12-13 |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=UK, Ministry of Defence |date=2015 |title=British Army: Sexual Harassment Report |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446224/ADR005000-Sexual_Harassment_Report.pdf |access-date=2017-12-11}} |

|||

* US: |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Marshall |first1=A |last2=Panuzio |first2=J |last3=Taft |first3=C |year=2005 |title=Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen |journal=Clinical Psychology Review |language=en |volume=25 |issue=7 |pages=862–876 |doi=10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009 |pmid=16006025}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=US, Department of Defense |date=2017 |title=Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2016 |url=http://sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/FY16_Annual/FY16_SAPRO_Annual_Report.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190508115225/https://sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/FY16_Annual/FY16_SAPRO_Annual_Report.pdf |archive-date=2019-05-08 |access-date=2018-03-09}} |

|||

</ref> See, for example, [[Women in the military]] and [[Sexual orientation and gender identity in military service]]. |

|||

* Evidence from the UK and US that [[Recruit training|military training]] and employment lead to higher rates of mental health and behavioural problems than are usually found in civilian life, particularly after personnel have left the armed forces.<ref name="health2">* UK: |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=MacManus |first1=Deirdre |last2=Rona |first2=Roberto |last3=Dickson |first3=Hannah |last4=Somaini |first4=Greta |last5=Fear |first5=Nicola |last6=Wessely |first6=Simon |date=2015-01-01 |title=Aggressive and Violent Behavior Among Military Personnel Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: Prevalence and Link With Deployment and Combat Exposure |journal=Epidemiologic Reviews |volume=37 |issue=1 |pages=196–212 |doi=10.1093/epirev/mxu006 |issn=0193-936X |pmid=25613552 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Goodwin |first1=L. |last2=Wessely |first2=S. |last3=Hotopf |first3=M. |last4=Jones |first4=M. |last5=Greenberg |first5=N. |last6=Rona |first6=R. J. |last7=Hull |first7=L. |last8=Fear |first8=N. T. |date=2015 |title=Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population? |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=45 |issue=9 |pages=1881–1891 |doi=10.1017/s0033291714002980 |issn=0033-2917 |pmid=25602942 |s2cid=3026974}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=MacManus |first1=Deirdre |last2=Dean |first2=Kimberlie |last3=Jones |first3=Margaret |last4=Rona |first4=Roberto J |last5=Greenberg |first5=Neil |last6=Hull |first6=Lisa |last7=Fahy |first7=Tom |last8=Wessely |first8=Simon |last9=Fear |first9=Nicola T |year=2013 |title=Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study |journal=The Lancet |language=en |volume=381 |issue=9870 |pages=907–917 |doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60354-2 |pmid=23499041 |s2cid=606331 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Thandi |first1=Gursimran |last2=Sundin |first2=Josefin |last3=Ng-Knight |first3=Terry |last4=Jones |first4=Margaret |last5=Hull |first5=Lisa |last6=Jones |first6=Norman |last7=Greenberg |first7=Neil |last8=Rona |first8=Roberto J. |last9=Wessely |first9=Simon |year=2015 |title=Alcohol misuse in the United Kingdom Armed Forces: A longitudinal study |journal=Drug and Alcohol Dependence |language=en |volume=156 |pages=78–83 |doi=10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.033 |pmid=26409753}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Buckman |first1=Joshua E. J. |last2=Forbes |first2=Harriet J. |last3=Clayton |first3=Tim |last4=Jones |first4=Margaret |last5=Jones |first5=Norman |last6=Greenberg |first6=Neil |last7=Sundin |first7=Josefin |last8=Hull |first8=Lisa |last9=Wessely |first9=Simon |date=2013-06-01 |title=Early Service leavers: a study of the factors associated with premature separation from the UK Armed Forces and the mental health of those that leave early |journal=European Journal of Public Health |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=410–415 |doi=10.1093/eurpub/cks042 |issn=1101-1262 |pmid=22539627 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Jones |first1=M. |last2=Sundin |first2=J. |last3=Goodwin |first3=L. |last4=Hull |first4=L. |last5=Fear |first5=N. T. |last6=Wessely |first6=S. |last7=Rona |first7=R. J. |date=2013 |title=What explains post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in UK service personnel: deployment or something else? |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=43 |issue=8 |pages=1703–1712 |doi=10.1017/s0033291712002619 |issn=0033-2917 |pmid=23199850 |s2cid=21097249}} |

|||

* US |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Hoge |first1=Charles W. |last2=Castro |first2=Carl A. |last3=Messer |first3=Stephen C. |last4=McGurk |first4=Dennis |last5=Cotting |first5=Dave I. |last6=Koffman |first6=Robert L. |date=2004-07-01 |title=Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |volume=351 |issue=1 |pages=13–22 |citeseerx=10.1.1.376.5881 |doi=10.1056/nejmoa040603 |issn=0028-4793 |pmid=15229303}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Friedman |first1=M. J. |last2=Schnurr |first2=P. P. |last3=McDonagh-Coyle |first3=A. |date=June 1994 |title=Post-traumatic stress disorder in the military veteran |journal=The Psychiatric Clinics of North America |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=265–277 |doi=10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30113-8 |issn=0193-953X |pmid=7937358}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last=Bouffard |first=Leana Allen |date=2016-09-16 |title=The Military as a Bridging Environment in Criminal Careers: Differential Outcomes of the Military Experience |journal=Armed Forces & Society |language=en |volume=31 |issue=2 |pages=273–295 |doi=10.1177/0095327x0503100206 |s2cid=144559516}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Merrill |first1=Lex L. |last2=Crouch |first2=Julie L. |last3=Thomsen |first3=Cynthia J. |last4=Guimond |first4=Jennifer |last5=Milner |first5=Joel S. |date=August 2005 |title=Perpetration of severe intimate partner violence: premilitary and second year of service rates |journal=Military Medicine |volume=170 |issue=8 |pages=705–709 |doi=10.7205/milmed.170.8.705 |issn=0026-4075 |pmid=16173214 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Elbogen |first1=Eric B. |last2=Johnson |first2=Sally C. |last3=Wagner |first3=H. Ryan |last4=Sullivan |first4=Connor |last5=Taft |first5=Casey T. |last6=Beckham |first6=Jean C. |date=2014-05-01 |title=Violent behaviour and post-traumatic stress disorder in US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans |journal=The British Journal of Psychiatry |language=en |volume=204 |issue=5 |pages=368–375 |doi=10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134627 |issn=0007-1250 |pmc=4006087 |pmid=24578444}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

* Evidence from Germany, Israel, the UK, and the US that [[Military recruitment|recruiting practices]] sanitise war, glorify the role of [[military personnel]], and obscure the risks and obligations of military employment, thereby misleading potential recruits, particularly [[Adolescence|adolescents]] from [[Economic inequality|socio-economically deprived]] backgrounds.<ref name="recruiting2">* Germany |

|||

** {{Cite book |last=Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns |title=Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany |year=2016}} |

|||

* Israel |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=New Profile |date=2004 |title=The New Profile Report on Child Recruitment in Israel |url=https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://new.newprofile.org/sites/default/files/infokits/english.pdf |access-date=2017-12-10}} |

|||

* UK |

|||

** {{Cite web |author1=Gee, D |author2=Goodman, A |title=Army visits London's poorest schools most often |url=http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180529080003/http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |archive-date=2018-05-29 |access-date=2017-12-10}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee |first=D |date=2008 |title=Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom |url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171213204740/https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |archive-date=2017-12-13 |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee |first=D |date=2017 |title=The First Ambush? Effects of army training and employment |url=http://vfpuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-First-Ambush-Effects-of-army-training-and-employment-WEB.pdf |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Gee |first1=David |last2=Taylor |first2=Rachel |date=2016-11-01 |title=Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army? |journal=The RUSI Journal |volume=161 |issue=6 |pages=36–48 |doi=10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837 |issn=0307-1847 |s2cid=157986637}} |

|||

* US |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Hagopian |first1=Amy |last2=Barker |first2=Kathy |date=2011-01-01 |title=Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health? |journal=American Journal of Public Health |volume=101 |issue=1 |pages=19–23 |doi=10.2105/ajph.2009.183418 |issn=0090-0036 |pmc=3000735 |pmid=21088269}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=American Public Health Association |date=2012 |title=Cessation of Military Recruiting in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools |url=https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/23/11/19/cessation-of-military-recruiting-in-public-elementary-and-secondary-schools |access-date=2017-12-13 |website=www.apha.org}} |

|||

** {{Cite news |title=Soldiers of Misfortune: Abusive U.S. Military Recruitment and Failure to Protect Child Soldiers |language=en |work=American Civil Liberties Union |url=https://www.aclu.org/other/soldiers-misfortune-abusive-us-military-recruitment-and-failure-protect-child-soldiers |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{cite journal |author=Diener, Sam |author2=Munro, Jamie |date=June–July 2005 |title=Military Money for College: A Reality Check |url=http://www.peaceworkmagazine.org/pwork/0506/050607.htm |url-status=dead |journal=Peacework |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061011153323/http://www.peaceworkmagazine.org/pwork/0506/050607.htm |archive-date=2006-10-11}} |

|||

** {{cite news |date=2005-05-20 |title=Amid Scandal, Recruitment Halts |work=CBS News |url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/05/20/national/main696991.shtml}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

* Evidence from Germany, the UK, and elsewhere that recruiters target, and capitalise on the precarious position of socio-economically deprived young people as potential recruits.<ref name="youngtarget2">* Germany |

|||

** {{Cite book |last=Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns |title=Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany |year=2016}} |

|||

* UK |

|||

** {{Cite news |last=Morris |first=Steven |date=2017-07-09 |title=British army is targeting working-class young people, report shows |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/09/british-army-is-targeting-working-class-young-people-report-shows |access-date=2017-12-08 |issn=0261-3077}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee |first=D |date=2008 |title=Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom |url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171213204740/https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/informed-choice-armed-forces-recruitment-practice-united-kingdom |archive-date=2017-12-13 |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |author1=Gee, D |author2=Goodman, A |title=Army visits London's poorest schools most often |url=http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180529080003/http://www.informedchoice.org.uk/armyvisitstoschools.pdf |archive-date=2018-05-29 |access-date=2017-12-10}} |

|||

* US |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last=Segal, D R |display-authors=et al |date=1998 |title=The all-volunteer force in the 1970s |journal=Social Science Quarterly |volume=72 |issue=2 |pages=390–411 |jstor=42863796}} |

|||

* Other |

|||

** Brett, Rachel, and Irma Specht. Young Soldiers: Why They Choose to Fight. Boulder: [[Lynne Rienner Publishers]], 2004. {{ISBN|1-58826-261-8}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |title=Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review: Children and conflict in a changing world |url=https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_49985.html |access-date=2017-12-08 |website=UNICEF}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

* The fact that some armed forces rely on children aged 16 or 17 to fill their ranks, and evidence from Australia, Israel, the UK and from the Vietnam era in the US that these youngest recruits are most likely to be adversely affected by the demands and risks of military life.<ref name="minors2">* Australia |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Australia, Department of Defence |date=2008 |title=Defence Instructions General: Management and administration of Australian Defence Force members under 18 years of age |url=https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/-/media/DFR/Files/DFT_Document_MembersUnder18Policy_20080422.pdf |access-date=2017-11-17}} |

|||

* Israel |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Milgrom |first1=C. |last2=Finestone |first2=A. |last3=Shlamkovitch |first3=N. |last4=Rand |first4=N. |last5=Lev |first5=B. |last6=Simkin |first6=A. |last7=Wiener |first7=M. |date=January 1994 |title=Youth is a risk factor for stress fracture. A study of 783 infantry recruits |journal=The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume |volume=76 |issue=1 |pages=20–22 |doi=10.1302/0301-620X.76B1.8300674 |issn=0301-620X |pmid=8300674}} |

|||

* UK |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=UK, Ministry of Defence |date=2017 |title=UK armed forces suicide and open verdict deaths: 2016 |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-suicide-and-open-verdict-deaths-2016 |access-date=2017-12-13 |website=www.gov.uk |language=en}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Blacker |first1=Sam D. |last2=Wilkinson |first2=David M. |last3=Bilzon |first3=James L. J. |last4=Rayson |first4=Mark P. |date=March 2008 |title=Risk factors for training injuries among British Army recruits |journal=Military Medicine |volume=173 |issue=3 |pages=278–286 |doi=10.7205/milmed.173.3.278 |issn=0026-4075 |pmid=18419031 |doi-access=}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Kapur |first1=Navneet |last2=While |first2=David |last3=Blatchley |first3=Nick |last4=Bray |first4=Isabelle |last5=Harrison |first5=Kate |date=2009-03-03 |title=Suicide after Leaving the UK Armed Forces —A Cohort Study |journal=PLOS Medicine |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=e1000026 |doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000026 |issn=1549-1676 |pmc=2650723 |pmid=19260757 |doi-access=free }} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee, D and Goodman, A |date=2013 |title=Young age at Army enlistment is associated with greater war zone risks: An analysis of British Army fatalities in Afghanistan |url=https://www.forceswatch.net/resources/young-age-army-enlistment-associated-greater-war-zone-risks-analysis-british-army-fataliti |access-date=2017-12-13 |website=www.forceswatch.net |language=en}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Gee |first1=David |last2=Taylor |first2=Rachel |date=2016-11-01 |title=Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army? |journal=The RUSI Journal |volume=161 |issue=6 |pages=36–48 |doi=10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837 |issn=0307-1847 |s2cid=157986637}} |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Gee |first=D |date=2017 |title=The First Ambush? Effects of army training and employment |url=http://vfpuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-First-Ambush-Effects-of-army-training-and-employment-WEB.pdf |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

* US |

|||

** {{Cite web |last=Knapik |display-authors=et al |date=2004 |title=A review of the literature on attrition from the military services: Risk factors for attrition and strategies to reduce attrition |url=http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA427744 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170809161922/http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA427744 |archive-date=August 9, 2017 |access-date=2017-12-13}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=King |first1=D. W. |last2=King |first2=L. A. |last3=Foy |first3=D. W. |last4=Gudanowski |first4=D. M. |date=June 1996 |title=Prewar factors in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans |journal=Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology |volume=64 |issue=3 |pages=520–531 |doi=10.1037/0022-006x.64.3.520 |issn=0022-006X |pmid=8698946}} |

|||

** {{Cite journal |last1=Schnurr |first1=Paula P. |last2=Lunney |first2=Carole A. |last3=Sengupta |first3=Anjana |date=April 2004 |title=Risk factors for the development versus maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder |journal=Journal of Traumatic Stress |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=85–95 |citeseerx=10.1.1.538.7819 |doi=10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022614.21794.f4 |issn=0894-9867 |pmid=15141781 |s2cid=12728307}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Armed forces spokespeople have defended the ''status quo'' by recourse to the following: |

Armed forces spokespeople have defended the ''status quo'' by recourse to the following: |

||

* The |

* The view that military organizations provide a valuable public service. |

||

| ⚫ | * |

||

* |

* Anecdotal evidence that military employment benefits young people.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hansard |date=2016 |title=Armed Forces Bill 2016 (col. 1211) |url=https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2016-04-27/debates/0062984F-41E4-49A7-8471-E7381998CF8F/ArmedForcesBill |access-date=2017-12-13 |website=hansard.parliament.uk |language=en}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * The view that duty of care policies protect recruits from harm.<ref name=":114">{{Cite web |last=Hansard |date=2016 |title=Armed Forces Bill 2016 (col. 1210) |url=https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2016-04-27/debates/0062984F-41E4-49A7-8471-E7381998CF8F/ArmedForcesBill |access-date=2017-12-13 |website=hansard.parliament.uk |language=en}}</ref> |

||

== Recruitment slogans and images == |

== Recruitment slogans and images == |

||

| Line 106: | Line 180: | ||

=== Slogans === |

=== Slogans === |

||

Armed forces have made effective use of short [[slogan]]s to inspire young people to enlist, with themes ranging from [[personal development]] (particularly personal power), societal service, and [[Patriotism|patriotic duty]]. For example, as of 2017 current slogans included: |

Armed forces have made effective use of short [[slogan]]s to inspire young people to enlist, with themes ranging from [[personal development]] (particularly personal power), societal service, and [[Patriotism|patriotic duty]]. For example, as of 2017 current slogans included: |

||

* 'Live a Life Less Ordinary.' ([[Indian Army]]) |

|||

* 'Army strong.' ([[United States Army|US Army]]). |

* 'Army strong.' ([[United States Army|US Army]]). |

||

* 'Be the Best.' ([[British Army]]). |

* 'Be the Best.' ([[British Army]]). |

||

| Line 111: | Line 186: | ||

* 'We. Serve. Germany.' ['Wir. Dienen. Deutschland.'] ([[Bundeswehr|German armed forces]]). |

* 'We. Serve. Germany.' ['Wir. Dienen. Deutschland.'] ([[Bundeswehr|German armed forces]]). |

||

* 'For me, for others.' ['Pour moi, pour les autres.'] ([[French Army]]). |

* 'For me, for others.' ['Pour moi, pour les autres.'] ([[French Army]]). |

||

* 'Join the fight for Israel.' ([[Israel Defense Forces]]). |

|||

{{Further|Slogans of the United States Army}} |

{{Further|Slogans of the United States Army}} |

||

| Line 117: | Line 191: | ||

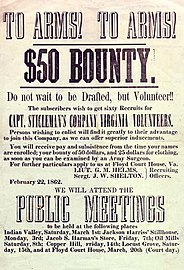

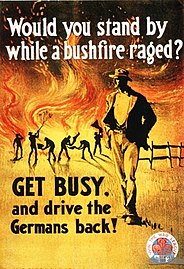

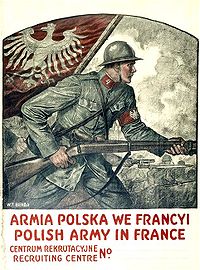

A '''recruitment poster''' is a [[poster]] used in advertisement to [[recruitment|recruit]] people into an organization, and has been a common method of military recruitment. |

A '''recruitment poster''' is a [[poster]] used in advertisement to [[recruitment|recruit]] people into an organization, and has been a common method of military recruitment. |

||

<gallery mode=packed heights=180> |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="180"> |

||

File:To Arms Confederate Enlistment Poster 1862.jpg|"To Arms! To Arms!" Recruitment poster for [[Confederate States of America]]. [[Floyd County, Virginia]], 1862. |

File:To Arms Confederate Enlistment Poster 1862.jpg|"To Arms! To Arms!" Recruitment poster for [[Confederate States of America]]. [[Floyd County, Virginia]], 1862. |

||