John Rainolds: Difference between revisions

m →Life |

m Removing from Category:English translators Diffusing per WP:DIFFUSE and/or WP:ALLINCLUDED using Cat-a-lot |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 18 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|English theologian (1549–1607)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2021}} |

||

{{Use British English|date=May 2012}} |

{{Use British English|date=May 2012}} |

||

{{infobox person |

{{infobox person |

||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

| birth_date=1549 |

| birth_date=1549 |

||

| birth_place=[[Pinhoe]], Exeter |

| birth_place=[[Pinhoe]], Exeter |

||

| death_date={{death date and age|1607|05|21|1549}} |

| death_date={{death date and age|df=yes|1607|05|21|1549}} |

||

| education=[[Corpus Christi College, Oxford]] |

| education=[[Corpus Christi College, Oxford]] |

||

| known_for=Work on the [[King James Bible]] |

| known_for=Work on the [[King James Bible]] |

||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

==Life== |

==Life== |

||

He was born about [[Michaelmas]] 1549 at [[Pinhoe]], near [[Exeter]]. He was fifth son of Richard Rainolds; [[William Rainolds]] was his brother. His uncle [[Thomas Rainolds]] held the living of Pinhoe from 1530 to 1537, and was subsequently Warden of [[Merton College, Oxford]], and [[Dean of Exeter]]. John Rainolds appears to have entered the [[University of Oxford]] originally at Merton, but on 29 April 1563 he was elected to a scholarship at [[Corpus Christi College, Oxford|Corpus Christi College]], where two of his brothers, Hierome and Edmond, were already fellows. He became probationary fellow on 11 October 1566, and full fellow two years later. |

He was born about [[Michaelmas]] 1549 at [[Pinhoe]], near [[Exeter]]. He was fifth son of Richard Rainolds; [[William Rainolds]] was his brother. His uncle [[Thomas Rainolds]] held the living of Pinhoe from 1530 to 1537, and was subsequently Warden of [[Merton College, Oxford]], and [[Dean of Exeter]]. John Rainolds appears to have entered the [[University of Oxford]] originally at Merton, but on 29 April 1563 he was elected to a scholarship at [[Corpus Christi College, Oxford|Corpus Christi College]], where two of his brothers, Hierome and Edmond, were already fellows. He became probationary fellow on 11 October 1566, and full fellow two years later. While a student at Corpus, he converted from Catholicism to Protestantism. |

||

On 15 October 1568 he graduated B.A.; and about this time he was assigned as tutor to [[Richard Hooker]].<ref name=DNB>{{cite DNB|wstitle=Rainolds, John}}</ref> In 1566 he played the female role of [[Hippolyta]] in a performance of the play ''[[Palamon and Arcite (Edwardes)|Palamon and Arcite]]'' at Oxford, as part of an elaborate entertainment for |

On 15 October 1568 he graduated B.A.; and about this time he was assigned as tutor to [[Richard Hooker]].<ref name=DNB>{{cite DNB|wstitle=Rainolds, John}}</ref> In 1566 he played the female role of [[Hippolyta]] in a performance of the play ''[[Palamon and Arcite (Edwardes)|Palamon and Arcite]]'' at Oxford, as part of an elaborate entertainment for [[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth I]]. She rewarded him with 8 [[angel (coin)|gold angels]]. Rainolds later recalled this youthful role with embarrassment, as he came to support Puritan objections to the theatre, being particularly critical of cross-dressing roles.<ref>Kirby Farrell, Kathleen M. Swaim, ''The Mysteries of Elizabeth I: Selections from English Literary Renaissance'', Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2003, p.37.</ref> |

||

In 1572–73 Rainolds was appointed reader in [[Ancient Greek language|Greek]], and his lectures on [[Aristotle]]'s ''Rhetoric'' made his reputation. In 1576 he objected to the proposal that [[Antonio de Corro]] should be allowed to proceed [[Doctor of Divinity]]; and at the same time he was instrumental in having [[Francesco Pucci]] expelled from the university, Pucci being an associate and ally of Corro, who had moved against orthodox Calvinist positions.<ref name=DNB/><ref>Secor, Philip Bruce (1999) ''Richard Hooker: Prophet of Anglicanism'', p. 96.</ref> |

In 1572–73 Rainolds was appointed reader in [[Ancient Greek language|Greek]], and his lectures on [[Aristotle]]'s ''Rhetoric'' made his reputation. In 1576 he objected to the proposal that [[Antonio de Corro]] should be allowed to proceed [[Doctor of Divinity]]; and at the same time he was instrumental in having [[Francesco Pucci]] expelled from the university, Pucci being an associate and ally of Corro, who had moved against orthodox Calvinist positions.<ref name=DNB/><ref>Secor, Philip Bruce (1999) ''Richard Hooker: Prophet of Anglicanism'', p. 96.</ref> Rainolds resigned his readership in 1578.<ref name=DNB/> The popular, young scholar was promoted as a candidate for college president by many university authorities in 1579, when it was thought to be an opening for the position.<ref>"Corpus Christi College." ''A History of the County of Oxford'': Volume 3, the University of Oxford. Eds. H E Salter, and Mary D Lobel. London: Victoria County History, 1954. 219-228. [http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp219-228. British History Online]{{Dead link|date=October 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}. Retrieved 8 February 2020.</ref> |

||

In the early 1580s, in the aftermath of [[Edmund Campion]]'s strenuous defence of [[Catholic]] principles, [[Francis Walsingham]] sent the Jesuit [[John Hart (Jesuit)|John Hart]] to Rainolds for an extended discussion. Hart conceded to Rainolds on the [[deposing power of the Pope]], at least according to the [[Protestant]] perspective, and an account was published in ''The summe of the conference betweene John Rainoldes and John Hart'' (1584).<ref>{{cite ODNB|id=23029|title=Rainolds, John|first=Mordechai|last=Feingold}}</ref> Unable to agree with the president of Corpus, [[William Cole (Puritan)|William Cole]], Rainolds then gave up his fellowship in 1586, and became a tutor at [[Queen's College, Oxford|Queen's College]]. In the same year Rainolds was appointed to a temporary lectureship, founded by Walsingham, for anti-Catholic polemical theology.<ref name=DNB/> |

|||

In 1589 the [[Regius Chair of Divinity at Oxford]] fell vacant. Rainolds had reason to anticipate the position would be his, but the Queen objected, and [[Thomas Holland (translator)|Thomas Holland]] was appointed. Rainolds's lectureship was continued by Walsingham.<ref>Lawrence D. Green, ''John Rainolds's Oxford Lectures'' (1986), p. 33; [https://books.google.com/books?id=77RPL09TOTIC&pg=PA33 Google Books]</ref> |

In 1589 the [[Regius Chair of Divinity at Oxford]] fell vacant. Rainolds had reason to anticipate the position would be his, but the Queen objected, and [[Thomas Holland (translator)|Thomas Holland]] was appointed. Rainolds's lectureship was continued by Walsingham.<ref>Lawrence D. Green, ''John Rainolds's Oxford Lectures'' (1986), p. 33; [https://books.google.com/books?id=77RPL09TOTIC&pg=PA33 Google Books]</ref> |

||

| Line 25: | Line 26: | ||

By this time he had acquired a considerable reputation as a disputant on the Puritan side, and the story goes that [[Elizabeth I of England|Elizabeth I]] visiting the university in 1592 "schooled him for his obstinate preciseness, willing him to follow her laws, and not run before them." |

By this time he had acquired a considerable reputation as a disputant on the Puritan side, and the story goes that [[Elizabeth I of England|Elizabeth I]] visiting the university in 1592 "schooled him for his obstinate preciseness, willing him to follow her laws, and not run before them." |

||

In 1593 Rainolds was made dean of [[Lincoln College, Oxford]] and/or of |

In 1593 Rainolds was made dean of [[Lincoln College, Oxford]] and/or of [[Lincoln Cathedral]]. The fellows of Corpus were anxious to replace Cole with Rainolds, and an exchange was effected, Rainolds being elected president in December 1598. |

||

==Creation of the King James Version of the |

==Creation of the King James Version of the Bible== |

||

The chief events of his subsequent career were his share in the [[Hampton Court Conference]], where he was the most prominent representative of the [[Puritan]] party and received a good deal of favour from [[James I of England|the |

The chief events of his subsequent career were his share in the [[Hampton Court Conference]], where he was the most prominent representative of the [[Puritan]] party and received a good deal of favour from [[James I of England|the King]]. |

||

During the Conference, the Puritans, led by Rainolds as spokesperson, directly questioned James about their grievances. However, almost every request brought forward by Rainolds was immediately denied or disputed by James.<ref>See Adam Nicolson, ''God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible'' (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), pp. 53–57</ref> At some point during the course of Rainolds' pleading before the king, Rainolds made a request that "one only translation of the Bible . . . [be] declared authentical, and read in the church".<ref>Alister E. McGrath, ''In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture'' (New York: Doubleday, 2001), p. 161</ref> Whether Rainolds was asking for a new translation or simply for a direction to authorize only one of the existing English translations, most took Rainolds' words as a request for the former.<ref>In the semiofficial proceedings of William Barlow, it is reported, "After that, he [Rainolds] moved his Majesty that there be a new translation of the Bible because those which were allowed in the reigns of Henry the eighth and Edward the sixth were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the original". See Olga S. Opfell, ''The King James Bible Translators'' (London: McFarland, 1982), pp. 6–7</ref> James readily agreed to a new translation. |

|||

During the creation of the [[King James Version]] of the Bible, he worked with the group who undertook the translation of [[Nevi'im|the Prophets]]. |

|||

During the creation of the subsequent drafting of the new translation of the Bible, Rainolds worked as a part of the group which undertook the translation of [[Nevi'im|the Prophets]]. The group met weekly in Rainolds' lodgings in Corpus. Despite being afflicted by failing eyesight and gout, Rainolds continued the work of translation to the end of his life, even being carried into the meeting room. |

|||

==Death== |

==Death== |

||

Rainolds died of [[tuberculosis|consumption]] on 21 May 1607, leaving a great reputation for scholarship and high character. On his deathbed he earnestly desired absolution according to the form of the Church of England, and received it from Dr. [[Thomas Holland (translator)]], whose hand he affectionately kissed. He is buried in the chapel of Corpus Christi. |

|||

[[File:Church History of Britain by Thomas Fuller (1837).jpg|thumb|left|The Church History of Britain by Thomas Fuller (1837) page 1]] |

|||

[[File:Church History of Britain by Thomas Fuller (1837) part 2.jpg|thumb|centre|...continued]] |

|||

==Works== |

==Works== |

||

| Line 72: | Line 79: | ||

[[Category:Deans of Lincoln]] |

[[Category:Deans of Lincoln]] |

||

[[Category:17th-century deaths from tuberculosis]] |

[[Category:17th-century deaths from tuberculosis]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Writers from Exeter]] |

||

[[Category:16th-century translators]] |

[[Category:16th-century English translators]] |

||

[[Category:English translators]] |

|||

[[Category:Anglican biblical scholars]] |

[[Category:Anglican biblical scholars]] |

||

[[Category:Tuberculosis deaths in England]] |

|||

[[Category:17th-century Anglican theologians]] |

|||

[[Category:16th-century Anglican theologians]] |

|||

Revision as of 03:41, 30 March 2024

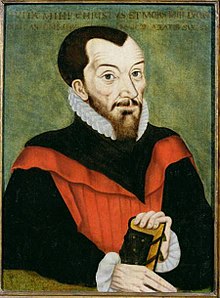

John Rainolds | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1549 Pinhoe, Exeter |

| Died | 21 May 1607 (aged 57–58) |

| Bildung | Corpus Christi College, Oxford |

| Known for | Work on the King James Bible |

John Rainolds (or Reynolds) (1549 – 21 May 1607) was an English academic and churchman, of Puritan views. He is remembered for his role in the Authorized Version of the Bible, a project of which he was initiator.

Leben

He was born about Michaelmas 1549 at Pinhoe, near Exeter. He was fifth son of Richard Rainolds; William Rainolds was his brother. His uncle Thomas Rainolds held the living of Pinhoe from 1530 to 1537, and was subsequently Warden of Merton College, Oxford, and Dean of Exeter. John Rainolds appears to have entered the University of Oxford originally at Merton, but on 29 April 1563 he was elected to a scholarship at Corpus Christi College, where two of his brothers, Hierome and Edmond, were already fellows. He became probationary fellow on 11 October 1566, and full fellow two years later. While a student at Corpus, he converted from Catholicism to Protestantism.

On 15 October 1568 he graduated B.A.; and about this time he was assigned as tutor to Richard Hooker.[1] In 1566 he played the female role of Hippolyta in a performance of the play Palamon and Arcite at Oxford, as part of an elaborate entertainment for Queen Elizabeth I. She rewarded him with 8 gold angels. Rainolds later recalled this youthful role with embarrassment, as he came to support Puritan objections to the theatre, being particularly critical of cross-dressing roles.[2]

In 1572–73 Rainolds was appointed reader in Greek, and his lectures on Aristotle's Rhetoric made his reputation. In 1576 he objected to the proposal that Antonio de Corro should be allowed to proceed Doctor of Divinity; and at the same time he was instrumental in having Francesco Pucci expelled from the university, Pucci being an associate and ally of Corro, who had moved against orthodox Calvinist positions.[1][3] Rainolds resigned his readership in 1578.[1] The popular, young scholar was promoted as a candidate for college president by many university authorities in 1579, when it was thought to be an opening for the position.[4]

In the early 1580s, in the aftermath of Edmund Campion's strenuous defence of Catholic principles, Francis Walsingham sent the Jesuit John Hart to Rainolds for an extended discussion. Hart conceded to Rainolds on the deposing power of the Pope, at least according to the Protestant perspective, and an account was published in The summe of the conference betweene John Rainoldes and John Hart (1584).[5] Unable to agree with the president of Corpus, William Cole, Rainolds then gave up his fellowship in 1586, and became a tutor at Queen's College. In the same year Rainolds was appointed to a temporary lectureship, founded by Walsingham, for anti-Catholic polemical theology.[1]

In 1589 the Regius Chair of Divinity at Oxford fell vacant. Rainolds had reason to anticipate the position would be his, but the Queen objected, and Thomas Holland was appointed. Rainolds's lectureship was continued by Walsingham.[6]

By this time he had acquired a considerable reputation as a disputant on the Puritan side, and the story goes that Elizabeth I visiting the university in 1592 "schooled him for his obstinate preciseness, willing him to follow her laws, and not run before them."

In 1593 Rainolds was made dean of Lincoln College, Oxford and/or of Lincoln Cathedral. The fellows of Corpus were anxious to replace Cole with Rainolds, and an exchange was effected, Rainolds being elected president in December 1598.

Creation of the King James Version of the Bible

The chief events of his subsequent career were his share in the Hampton Court Conference, where he was the most prominent representative of the Puritan party and received a good deal of favour from the King.

During the Conference, the Puritans, led by Rainolds as spokesperson, directly questioned James about their grievances. However, almost every request brought forward by Rainolds was immediately denied or disputed by James.[7] At some point during the course of Rainolds' pleading before the king, Rainolds made a request that "one only translation of the Bible . . . [be] declared authentical, and read in the church".[8] Whether Rainolds was asking for a new translation or simply for a direction to authorize only one of the existing English translations, most took Rainolds' words as a request for the former.[9] James readily agreed to a new translation.

During the creation of the subsequent drafting of the new translation of the Bible, Rainolds worked as a part of the group which undertook the translation of the Prophets. The group met weekly in Rainolds' lodgings in Corpus. Despite being afflicted by failing eyesight and gout, Rainolds continued the work of translation to the end of his life, even being carried into the meeting room.

Death

Rainolds died of consumption on 21 May 1607, leaving a great reputation for scholarship and high character. On his deathbed he earnestly desired absolution according to the form of the Church of England, and received it from Dr. Thomas Holland (translator), whose hand he affectionately kissed. He is buried in the chapel of Corpus Christi.

Works

- De Romanae ecclesiae idolatria (1596), dedicated to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, supporter of his theology lectures.[10]

References

- ^ a b c d . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Kirby Farrell, Kathleen M. Swaim, The Mysteries of Elizabeth I: Selections from English Literary Renaissance, Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2003, p.37.

- ^ Secor, Philip Bruce (1999) Richard Hooker: Prophet of Anglicanism, p. 96.

- ^ "Corpus Christi College." A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford. Eds. H E Salter, and Mary D Lobel. London: Victoria County History, 1954. 219-228. British History Online[permanent dead link]. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Feingold, Mordechai. "Rainolds, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23029. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Lawrence D. Green, John Rainolds's Oxford Lectures (1986), p. 33; Google Books

- ^ See Adam Nicolson, God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), pp. 53–57

- ^ Alister E. McGrath, In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture (New York: Doubleday, 2001), p. 161

- ^ In the semiofficial proceedings of William Barlow, it is reported, "After that, he [Rainolds] moved his Majesty that there be a new translation of the Bible because those which were allowed in the reigns of Henry the eighth and Edward the sixth were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the original". See Olga S. Opfell, The King James Bible Translators (London: McFarland, 1982), pp. 6–7

- ^ Paul E. J. Hammer, The Polarisation of Elizabethan Politics: the political career of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, 1585-1597 (1999), p. 301 note 165; Google Books.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Rainolds, John". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rainolds, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 863.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Rainolds, John". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rainolds, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 863.

Further reading

- J. W. Binns, Intellectual Culture in Elizabethan and Jacobean England: The Latin Writing of the Age, Leeds: Francis Cairns, 1990.

- Lawrence D. Green, "Introduction," John Rainolds's Oxford Lectures on Aristotles Rhetoric, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1986.

- Mordechai Feingold and Lawrence D. Green, "John Rainolds," British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500-1660, Second Series, DLB 281, Detroit: Gale, 2003, pp. 249–259.

- Feingold, Mordechai. "Rainolds, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23029. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1549 births

- 1607 deaths

- 16th-century English theologians

- 16th-century Puritans

- Translators of the King James Version

- Presidents of Corpus Christi College, Oxford

- Deans of Lincoln

- 17th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Writers from Exeter

- 16th-century English translators

- Anglican biblical scholars

- Tuberculosis deaths in England

- 17th-century Anglican theologians

- 16th-century Anglican theologians