Accident: Difference between revisions

m move misplaced templates |

Deejaypedia (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 31 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Unforeseen event, often with a negative outcome}} |

{{Short description|Unforeseen event, often with a negative outcome}} |

||

{{Other uses|Accident (disambiguation)|Accidental (disambiguation)}} |

{{Other uses|Accident (disambiguation)|Accidental (disambiguation)}} |

||

[[File:Hillsborough Memorial, Anfield.jpg|right|thumb|A memorial to the |

[[File:Hillsborough Memorial, Anfield.jpg|right|thumb|A memorial to the 97 victims of the [[Hillsborough disaster]].]] |

||

| ⚫ | An '''accident''' is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Woodward|first=Gary C.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ce_WAAAAQBAJ|title=The Rhetoric of Intention in Human Affairs|year=2013|publisher=Lexington Books|isbn=978-0-7391-7905-5|pages=41|language=en|quote=Since 'accidents' by definition deprive us of first-order human causes…}}</ref> The term ''accident'' implies that nobody should be [[Blame|blamed]], but the event may have been caused by [[Risk assessment|unrecognized or unaddressed risks]]. Most researchers who study [[unintentional injury]] avoid using the term ''accident'' and focus on factors that increase risk of severe injury and that reduce injury incidence and severity.<ref name=Robertson2015>{{cite book | last = Robertson | first = Leon S. | title = Injury Epidemiology: Fourth Edition | year = 2015 | publisher = Lulu Books | url = http://www.nanlee.net/ | access-date = 2017-12-09 | archive-date = 2018-01-26 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180126185850/http://www.nanlee.net/ | url-status = live }}</ref> For example, when a tree falls down during a [[wind storm]], its fall may not have been caused by humans, but the tree's type, size, health, location, or improper maintenance may have contributed to the result. Most [[Traffic collision|car wrecks]] are not true accidents; however, English speakers started using that word in the mid-20th century as a result of [[media manipulation]] by the US automobile industry.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

| ⚫ | An '''accident''' is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Woodward|first=Gary C.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ce_WAAAAQBAJ|title=The Rhetoric of Intention in Human Affairs| |

||

==Types== |

==Types== |

||

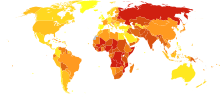

[[File:Unintentional injuries world map-Deaths per million persons-WHO2012.svg|thumb|Unintentional injury deaths per million persons in 2012 |

[[File:Unintentional injuries world map-Deaths per million persons-WHO2012.svg|thumb|Unintentional injury deaths per million persons in 2012 |

||

{{ |

{{Div col|small=yes|colwidth=10em}}{{legend|#ffff20|107–247}}{{legend|#ffe820|248–287}}{{legend|#ffd820|288–338}}{{legend|#ffc020|339–387}}{{legend|#ffa020|388–436}}{{legend|#ff9a20|437–505}}{{legend|#f08015|506–574}}{{legend|#e06815|575–655}}{{legend|#d85010|656–834}}{{legend|#d02010|835–1,165}}{{div col end}} |

||

]] |

]] |

||

===Physical and non-physical=== |

===Physical and non-physical=== |

||

Physical examples of accidents include unintended motor vehicle collisions, [[Fall prevention|falls]], being injured by touching something sharp or hot, or bumping into something while walking. |

Physical examples of accidents include unintended motor vehicle collisions, tongue biting while eating, electric shock by accidentally touching bare electric wire, drowning, [[Fall prevention|falls]], being injured by touching something sharp or hot, or bumping into something while walking. |

||

Non-physical examples are unintentionally revealing a [[secret]] or otherwise saying something incorrectly, accidental deletion of data, or forgetting an appointment. |

Non-physical examples are unintentionally revealing a [[secret]] or otherwise saying something incorrectly, accidental deletion of data, or forgetting an appointment. |

||

| Line 20: | Line 19: | ||

===Accidents by vehicle=== |

===Accidents by vehicle=== |

||

[[File:A. Provost - Versailles - Railroad Disaster.jpg|thumb|[[Versailles rail accident]] in 1842]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023|data on vehicular collisions}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Sailing ships]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | It has been argued by some critics that vehicle collisions are not truly accidents, given that they are mostly caused by preventable causes such as [[drunk driving]] and intentionally driving too fast, and as such should not be referred to as ''accidents''.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Stromberg|first=Joseph|date=2015-07-20|title=We don't say "plane accident." We shouldn't say "car accident" either.|url=https://www.vox.com/2015/7/20/8995151/crash-not-accident|access-date=2021-09-07|website=Vox|language=en|archive-date=2021-09-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210907052859/https://www.vox.com/2015/7/20/8995151/crash-not-accident|url-status=live}}</ref> Since 1994, the US [[National Highway Traffic Safety Administration]] has asked media and the public to not use the word ''accident'' to describe vehicle collisions.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Full article|Aviation accidents and incidents}} |

|||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

==== Bicycle accidents ==== |

|||

{{Full article|Bicycle safety}} |

|||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

==== Maritime incidents ==== |

|||

{{Full article|Maritime incident}} |

|||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

==== Traffic collisions ==== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Full article|Train wreck}} |

|||

{{Section expansion needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In the process industry, a primary accident may propagate to nearby units, resulting in a chain of accidents, which is called [[domino effect accident]]. |

In the process industry, a primary accident may propagate to nearby units, resulting in a chain of accidents, which is called [[domino effect accident]]. |

||

==Common causes== |

==Common causes== |

||

{{See also|Preventable causes of death}} |

{{See also|Preventable causes of death}} |

||

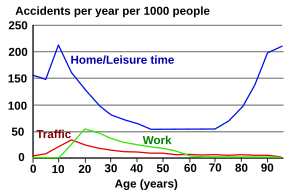

[[File:Accidents.svg|thumb| |

[[File:Accidents.svg|thumb|upright=1.3|Incidence of accidents (of a severity of resulting in seeking medical care), sorted by activity (in Denmark in 2002)]] |

||

Poisons, vehicle collisions and falls are the most common causes of fatal injuries. According to a 2005 survey of injuries sustained at home, which used data from the National Vital Statistics System of the United States [[National Center for Health Statistics]], falls, poisoning, and fire/burn injuries are the most common causes of death.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Runyan CW, Casteel C, Perkis D |title=Unintentional injuries in the home in the United States Part I: mortality |journal=Am J Prev Med |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=73–9 |date=January 2005 |pmid=15626560 |doi=10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.010 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

Poisons, vehicle collisions and falls are the most common causes of fatal injuries. According to a 2005 survey of injuries sustained at home, which used data from the National Vital Statistics System of the United States [[National Center for Health Statistics]], falls, poisoning, and fire/burn injuries are the most common causes of death.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Runyan CW, Casteel C, Perkis D |title=Unintentional injuries in the home in the United States Part I: mortality |journal=Am J Prev Med |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=73–9 |date=January 2005 |pmid=15626560 |doi=10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.010 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

||

| Line 40: | Line 56: | ||

==Accident models== |

==Accident models== |

||

[[File:Pyramid of risks.svg|thumb|[[Accident triangle]]s have been proposed to model the number of minor problems vs. the number of serious incidents. These include Heinrich's triangle<ref name="Heinreich 1931" /> and Frank E. Bird's accident ratio triangle (proposed in 1966 and shown above).]] |

[[File:Pyramid of risks.svg|thumb|[[Accident triangle]]s have been proposed to model the number of minor problems vs. the number of serious incidents. These include Heinrich's triangle<ref name="Heinreich 1931" /> and Frank E. Bird's accident ratio triangle (proposed in 1966 and shown above).]] |

||

Many models to characterize and analyze accidents have been proposed,<ref>A long list of books and papers is given in: {{cite book|title=Enhancing Occupational Safety and Health|url=https://archive.org/details/enhancingoccupat00tayl_968|url-access=limited|date=2004|author=Taylor, G.A.|author2=Easter, K.M.|author3=Hegney, R.P.|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=0750661976|pages=[https://archive.org/details/enhancingoccupat00tayl_968/page/n259 241]–245, see also |

Many models to characterize and analyze accidents have been proposed,<ref>A long list of books and papers is given in: {{cite book|title=Enhancing Occupational Safety and Health|url=https://archive.org/details/enhancingoccupat00tayl_968|url-access=limited|date=2004|author=Taylor, G.A.|author2=Easter, K.M.|author3=Hegney, R.P.|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=0750661976|pages=[https://archive.org/details/enhancingoccupat00tayl_968/page/n259 241]–245, see also pp. 140–141, 147–153, also on Kindle}}</ref> which can be classified by type. No single model is the sole correct approach.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Kjellen|first1=Urban|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wW9GDgAAQBAJ|title=Prevention of Accidents and Unwanted Occurrences: Theory, Methods, and Tools in Safety Management, Second Edition|last2=Albrechtsen|first2=Eirik|year=2017|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-4987-3666-4|pages=75|language=en}}</ref> Notable types and models include:<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.ohsbok.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/32-Models-of-causation-Safety.pdf |title=OHS Body of Knowledge |author1=Yvonne Toft |author2=Geoff Dell |author3=Karen K Klockner |author4=Allison Hutton |chapter=Models of Causation: Safety |editor=HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals Alliance) |publisher=Safety Institute of Australia Ltd. |date= 2012 |isbn=978-0-9808743-1-0 |access-date=2017-03-25 |archive-date=2017-02-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170225133142/http://www.ohsbok.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/32-Models-of-causation-Safety.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

* Sequential models |

* Sequential models |

||

** Domino |

** Domino theory<ref name="Heinreich 1931">{{cite book |author=H.W. Heinreich |year=1931 |title=Industrial Accident Prevention |publisher=McGraw-Hill}}</ref> |

||

** Loss |

** Loss causation model<ref>{{cite book|last1= Bird |first1= Frank E.|last2= Germain|first2 = George L. |date = 1985|title = Practical Loss Control Leadership|publisher = International Loss Control Institute |isbn = 978-0880610544|oclc=858460141}}</ref> |

||

* Complex linear models |

* Complex linear models |

||

** |

** Energy damage model<ref>Gibson, Haddon, Viner</ref>{{full citation needed|date=April 2022}} |

||

** Time sequence models |

** Time sequence models |

||

*** |

*** Generalized time sequence model<ref>Viner</ref>{{full citation needed|date=April 2022}} |

||

*** Accident |

*** Accident evolution and barrier function<ref>{{cite journal|last = Svenson|first = Ola|title = The Accident Evolution and Barrier Function (AEB) Model Applied to Incident Analysis in the Processing Industries|journal = Risk Analysis|date = September 1991|doi = 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1991.tb00635.x|volume = 11|issue = 3|pages = 499–507| pmid=1947355 | bibcode=1991RiskA..11..499S }}</ref> |

||

** Epidemiological models |

** Epidemiological models |

||

*** Gordon 1949 |

*** Gordon 1949{{Citation needed|date=February 2024}} |

||

*** Onward |

*** Onward mappings model based on resident pathogens metaphor<ref>{{cite book |chapter=Too Little and Too Late: A Commentary on Accident and Incident Reporting |last=Reason |first=James T. |year=1991 |pages=9–26 |title=Near Miss Reporting as a Safety Tool |publisher=Butterworth-Heinemann |editor1-last=Van Der Schaaf |editor1-first=T.W. |editor2-last=Lucas |editor2-first=D.A. |editor3-last=Hale |editor3-first=A.R.}}</ref> |

||

* Process model |

* Process model |

||

** Benner 1975 |

** Benner 1975{{Citation needed|date=February 2024}} |

||

* Systemic models |

* Systemic models |

||

** Rasmussen |

** Rasmussen |

||

** Reason |

** Reason model of system safety (embedding the [[Swiss cheese model]]) |

||

*** [[Healthcare error proliferation model]] |

*** [[Healthcare error proliferation model]] |

||

*** [[Human reliability]] |

*** [[Human reliability]] |

||

** Woods |

** Woods 1994{{Citation needed|date=February 2024}} |

||

* Non-linear models |

* Non-linear models |

||

** [[System accident]]<ref>{{cite book|last = Perrow|first = Charles |date= 1984|title =Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies|isbn = |

** [[System accident]]<ref>{{cite book|last = Perrow|first = Charles |date= 1984|title =Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies|isbn = 978-0465051434|publisher = Basic Books}}</ref> |

||

** Systems- |

** Systems-theoretic accident model and process (STAMP)<ref>{{cite journal|last = Leveson |first = Nancy|date = April 2004|journal = [[Safety Science]] |title = A new accident model for engineering safer systems|volume = 42|issue = 4|pages = 237–270|doi = 10.1016/S0925-7535(03)00047-X|citeseerx = 10.1.1.141.697}}</ref> |

||

** Functional |

** Functional resonance analysis Method ([https://functionalresonance.com/ FRAM])<ref>Hollnagel, 2012</ref> |

||

** Assertions that all existing models are insufficient<ref>Dekker 2011</ref> |

** Assertions that all existing models are insufficient<ref>Dekker 2011</ref>{{full citation needed|date=April 2022}} |

||

[[Ishikawa diagram]]s are sometimes used to illustrate [[root-cause analysis]] and [[five whys]] discussions. |

[[Ishikawa diagram]]s are sometimes used to illustrate [[root-cause analysis]] and [[five whys]] discussions. |

||

| Line 71: | Line 87: | ||

===General=== |

===General=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Accident analysis]] |

* [[Accident analysis]] |

||

** [[Root cause analysis]] |

** [[Root cause analysis]] |

||

* [[Accident-proneness]] |

* [[Accident-proneness]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Injury]] |

* [[Injury]] |

||

* [[Injury prevention]] |

** [[Injury prevention]] |

||

* [[List of accidents and disasters by death toll]] |

* [[List of accidents and disasters by death toll]] |

||

* [[Safety]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

===Transportation=== |

===Transportation=== |

||

* [[Air safety]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Bicycle safety]] |

* [[Bicycle safety]] |

||

* Road vehicle safety |

|||

* Car |

|||

** [[Automobile safety]] |

** [[Automobile safety]] |

||

** [[Traffic collision]] |

** [[Traffic collision]] |

||

* [[List of rail accidents]] |

* [[List of rail accidents]] |

||

* [[Tram accident]] |

* [[Tram accident]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Maritime incident]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

===Other specific topics=== |

===Other specific topics=== |

||

| Line 99: | Line 117: | ||

* [[Explosives safety]] |

* [[Explosives safety]] |

||

* [[Nuclear and radiation accidents]] |

* [[Nuclear and radiation accidents]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

** [[Safety data sheet]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

** [[Criticality accident]] |

** [[Criticality accident]] |

||

* [[Sports injury]] |

* [[Sports injury]] |

||

| Line 119: | Line 134: | ||

[[Category:Failure]] |

[[Category:Failure]] |

||

[[Category:Accident analysis| ]] |

[[Category:Accident analysis| ]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Revision as of 20:10, 25 April 2024

An accident is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans.[1] The term accident implies that nobody should be blamed, but the event may have been caused by unrecognized or unaddressed risks. Most researchers who study unintentional injury avoid using the term accident and focus on factors that increase risk of severe injury and that reduce injury incidence and severity.[2] For example, when a tree falls down during a wind storm, its fall may not have been caused by humans, but the tree's type, size, health, location, or improper maintenance may have contributed to the result. Most car wrecks are not true accidents; however, English speakers started using that word in the mid-20th century as a result of media manipulation by the US automobile industry.[3]

Types

Physical and non-physical

Physical examples of accidents include unintended motor vehicle collisions, tongue biting while eating, electric shock by accidentally touching bare electric wire, drowning, falls, being injured by touching something sharp or hot, or bumping into something while walking.

Non-physical examples are unintentionally revealing a secret or otherwise saying something incorrectly, accidental deletion of data, or forgetting an appointment.

Accidents by activity

- Accidents during the execution of work or arising out of it are called work accidents. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), more than 337 million accidents happen on the job each year, resulting, together with occupational diseases, in more than 2.3 million deaths annually.[4]

- In contrast, leisure-related accidents are mainly sports injuries.

Accidents by vehicle

This section needs expansion with: data on vehicular collisions. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

It has been argued by some critics that vehicle collisions are not truly accidents, given that they are mostly caused by preventable causes such as drunk driving and intentionally driving too fast, and as such should not be referred to as accidents.[3] Since 1994, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has asked media and the public to not use the word accident to describe vehicle collisions.[3]

Aviation accidents and incidents

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Bicycle accidents

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Maritime incidents

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Traffic collisions

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Train wrecks

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

Domino effect accidents

In the process industry, a primary accident may propagate to nearby units, resulting in a chain of accidents, which is called domino effect accident.

Common causes

Poisons, vehicle collisions and falls are the most common causes of fatal injuries. According to a 2005 survey of injuries sustained at home, which used data from the National Vital Statistics System of the United States National Center for Health Statistics, falls, poisoning, and fire/burn injuries are the most common causes of death.[5]

The United States also collects statistically valid injury data (sampled from 100 hospitals) through the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System administered by the Consumer Product Safety Commission.[6] This program was revised in 2000 to include all injuries rather than just injuries involving products.[6] Data on emergency department visits is also collected through the National Health Interview Survey.[7] In The U.S. the Bureau of Labor Statistics has available on their website extensive statistics on workplace accidents.[8]

Accident models

Many models to characterize and analyze accidents have been proposed,[10] which can be classified by type. No single model is the sole correct approach.[11] Notable types and models include:[12]

- Sequential models

- Complex linear models

- Energy damage model[14][full citation needed]

- Time sequence models

- Generalized time sequence model[15][full citation needed]

- Accident evolution and barrier function[16]

- Epidemiological models

- Gordon 1949[citation needed]

- Onward mappings model based on resident pathogens metaphor[17]

- Process model

- Benner 1975[citation needed]

- Systemic models

- Rasmussen

- Reason model of system safety (embedding the Swiss cheese model)

- Woods 1994[citation needed]

- Non-linear models

- System accident[18]

- Systems-theoretic accident model and process (STAMP)[19]

- Functional resonance analysis Method (FRAM)[20]

- Assertions that all existing models are insufficient[21][full citation needed]

Ishikawa diagrams are sometimes used to illustrate root-cause analysis and five whys discussions.

See also

Allgemein

- Occupational safety and health

- Safety

- Personal protective equipment

- Safety engineering

- Fail-safe

- Idiot-proof

- Poka-yoke

- Risk management

- Accident analysis

- Accident-proneness

- Injury

- List of accidents and disasters by death toll

Transport

- Bicycle safety

- Road vehicle safety

- List of rail accidents

- Tram accident

- Maritime incident

- Air safety

Other specific topics

- Aisles: Safety and regulatory considerations

- Explosives safety

- Nuclear and radiation accidents

- Sports injury

References

- ^ Woodward, Gary C. (2013). The Rhetoric of Intention in Human Affairs. Lexington Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7391-7905-5.

Since 'accidents' by definition deprive us of first-order human causes…

- ^ Robertson, Leon S. (2015). Injury Epidemiology: Fourth Edition. Lulu Books. Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ^ a b c Stromberg, Joseph (2015-07-20). "We don't say "plane accident." We shouldn't say "car accident" either". Vox. Archived from the original on 2021-09-07. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ "ILO Safety and Health at Work Archived 2022-01-19 at the Wayback Machine". International Labour Organization (ILO)

- ^ Runyan CW, Casteel C, Perkis D, et al. (January 2005). "Unintentional injuries in the home in the United States Part I: mortality". Am J Prev Med. 28 (1): 73–9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.010. PMID 15626560.

- ^ a b CPSC. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) Archived 2013-03-13 at the Wayback Machine. Database query available through: NEISS Injury Data Archived 2013-04-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NCHS. Emergency Department Visits Archived 2017-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. CDC.

- ^ "Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities". www.bls.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ a b H.W. Heinreich (1931). Industrial Accident Prevention. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ A long list of books and papers is given in: Taylor, G.A.; Easter, K.M.; Hegney, R.P. (2004). Enhancing Occupational Safety and Health. Elsevier. pp. 241–245, see also pp. 140–141, 147–153, also on Kindle. ISBN 0750661976.

- ^ Kjellen, Urban; Albrechtsen, Eirik (2017). Prevention of Accidents and Unwanted Occurrences: Theory, Methods, and Tools in Safety Management, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4987-3666-4.

- ^ Yvonne Toft; Geoff Dell; Karen K Klockner; Allison Hutton (2012). "Models of Causation: Safety". In HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals Alliance) (ed.). OHS Body of Knowledge (PDF). Safety Institute of Australia Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9808743-1-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-25. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- ^ Bird, Frank E.; Germain, George L. (1985). Practical Loss Control Leadership. International Loss Control Institute. ISBN 978-0880610544. OCLC 858460141.

- ^ Gibson, Haddon, Viner

- ^ Viner

- ^ Svenson, Ola (September 1991). "The Accident Evolution and Barrier Function (AEB) Model Applied to Incident Analysis in the Processing Industries". Risk Analysis. 11 (3): 499–507. Bibcode:1991RiskA..11..499S. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1991.tb00635.x. PMID 1947355.

- ^ Reason, James T. (1991). "Too Little and Too Late: A Commentary on Accident and Incident Reporting". In Van Der Schaaf, T.W.; Lucas, D.A.; Hale, A.R. (eds.). Near Miss Reporting as a Safety Tool. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 9–26.

- ^ Perrow, Charles (1984). Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465051434.

- ^ Leveson, Nancy (April 2004). "A new accident model for engineering safer systems". Safety Science. 42 (4): 237–270. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.141.697. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(03)00047-X.

- ^ Hollnagel, 2012

- ^ Dekker 2011

External links