New London, Connecticut: Difference between revisions

Magnolia677 (talk | contribs) Clean up/copyedit |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 17 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|City in Connecticut, United States}} |

{{short description|City in Connecticut, United States}} |

||

{{About||the county|New London County, Connecticut}} |

{{About||the county|New London County, Connecticut}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date= |

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

|name |

| name = New London |

||

|official_name |

| official_name = City of New London <!-- Change this and you break the "Seal" wikilink --> |

||

|settlement_type |

| settlement_type = [[List of municipalities in Connecticut|City]] |

||

|image_skyline |

| image_skyline = New London skyline from Fort Griswold, December 2017.jpg |

||

|imagesize |

| imagesize = |

||

|image_caption |

| image_caption = New London skyline from [[Fort Griswold]] |

||

|image_flag |

| image_flag = |

||

|image_seal |

| image_seal = Seal of City of New London.png |

||

|nickname |

| nickname = The Whaling City |

||

|motto |

| motto = ''[[Mare Liberum]]'' |

||

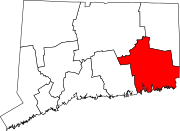

| image_map |

| image_map = {{switcher|[[File:New London County Connecticut Incorporated and Unincorporated areas New London Highlighted 2010.svg|250px|frameless|alt=New London's location within New London County and Connecticut]]| [[New London County, Connecticut|New London County]] and Connecticut|[[File:Southeastern Connecticut incorporated and unincorporated areas New London highlighted.svg|250px|frameless|alt=New London's location within the Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region and the state of Connecticut]]| [[Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region, Connecticut|Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region]] and Connecticut|default=1}} |

||

| image_map1 |

| image_map1 = {{maplink|frame=yes|plain=yes|frame-align=center|frame-width=250|frame-height=200|frame-coord=SWITCH:{{coord|qid=Q49146}}###{{coord|qid=Q779}}###{{coord|41|21|20|N|72|05|58|W}}|zoom=SWITCH:10;6;3|type=SWITCH:shape-inverse;point;point|marker=city|stroke-width=2|stroke-color=#000000|id2=SWITCH:Q49146;Q779;Q30|type2=shape|fill2=#ffffff|fill-opacity2=SWITCH:0;0.1;0.1|stroke-width2=2|stroke-color2=#808080|stroke-opacity2=SWITCH:0;1;1|switch=New London;Connecticut;the United States}} |

||

|coordinates |

| coordinates = {{coord|41|21|20|N|72|05|58|W|region:US-CT|display=inline,title}} |

||

| subdivision_type |

| subdivision_type = Country |

||

| subdivision_name |

| subdivision_name = United States |

||

| subdivision_type1 |

| subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state]] |

||

| subdivision_name1 |

| subdivision_name1 = [[Connecticut]] |

||

| subdivision_type2 |

| subdivision_type2 = [[County (United States)|County]] |

||

| subdivision_name2 |

| subdivision_name2 = [[New London County, Connecticut|New London]] |

||

| subdivision_type3 |

| subdivision_type3 = [[Councils of governments in Connecticut|Region]] |

||

| subdivision_name3 |

| subdivision_name3 = [[Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region, Connecticut|Southeastern CT]] |

||

|established_title |

| established_title = Settled |

||

|established_date |

| established_date = 1646 (Pequot Plantation) |

||

|established_title2 |

| established_title2 = Named |

||

|established_date2 |

| established_date2 = 1658 (New London) |

||

|established_title3 |

| established_title3 = Incorporated (city) |

||

|established_date3 |

| established_date3 = 1784 |

||

|named_for |

| named_for = [[London]], England |

||

<!-- Government -->| government_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web |title=Office of the Mayor |url=https://newlondonct.org/mayor |website=newlondonct.org |access-date=June 2, 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=City Council |url=https://newlondonct.org/administration/council |website=newlondonct.org |access-date=June 2, 2024}}</ref>{{Update after|2024|11|05|reason=election day}} |

|||

<!-- Government --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|government_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web | title = Office of the Mayor | publisher = City of New London, Connecticut | url = http://www.ci.new-london.ct.us/content/7429/7469/default.aspx | access-date = June 11, 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Council Members | publisher = City of New London, Connecticut | url = http://www.ci.new-london.ct.us/content/7429/7471/7511.aspx | access-date = June 11, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| leader_title = Mayor |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| |

| leader_name = Michael E. Passero |

||

|leader_name = Michael E. Passero |

|||

{{Collapsible list |

{{Collapsible list |

||

| title = City Council |

| title = City Council |

||

| Line 42: | Line 41: | ||

| frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; |

| frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; |

||

| list_style = text-align:left;display:none; |

| list_style = text-align:left;display:none; |

||

| 1 = |

| 1 = Akil Peck |

||

| 2 = Efrain Dominguez, Jr. |

| 2 = Efrain Dominguez, Jr. |

||

| 3 = |

| 3 = Alma D. Nartatez |

||

| 4 = |

| 4 = Jefferey P. Hart |

||

| 5 = |

| 5 = Jocelyn Rosario |

||

| 6 = |

| 6 = Reona M. Dyess}} |

||

|unit_pref = Imperial |

| unit_pref = Imperial |

||

|area_magnitude |

| area_magnitude = |

||

|area_total_km2 |

| area_total_km2 = 27.43 |

||

|area_total_sq_mi |

| area_total_sq_mi = 10.60 |

||

|area_land_km2 |

| area_land_km2 = 14.52 |

||

|area_land_sq_mi |

| area_land_sq_mi = 5.61 |

||

|area_water_km2 |

| area_water_km2 = 12.91 |

||

|area_water_sq_mi |

| area_water_sq_mi = 4.98 |

||

|area_urban_km2 |

| area_urban_km2 = 318.66 |

||

|area_urban_sq_mi |

| area_urban_sq_mi = 123.03 |

||

|area_metro_km2 |

| area_metro_km2 = |

||

|area_metro_sq_mi |

| area_metro_sq_mi = |

||

|elevation_m |

| elevation_m = 17 |

||

|elevation_ft |

| elevation_ft = 56 |

||

|population_total |

| population_total = 27367 |

||

|population_as_of |

| population_as_of = [[2020 United States Census|2020]] |

||

|population_footnotes |

| population_footnotes = |

||

|population_density_km2 |

| population_density_km2 = 1879.6 |

||

|population_density_sq_mi = |

| population_density_sq_mi = |

||

|population_urban |

| population_urban = |

||

|population_metro |

| population_metro = 274055 |

||

|population_density_metro_km2 |

| population_density_metro_km2 = |

||

|population_density_metro_sq_mi |

| population_density_metro_sq_mi = |

||

|population_note |

| population_note = |

||

|postal_code_type |

| postal_code_type = [[ZIP Code]] |

||

|postal_code |

| postal_code = 06320 |

||

|area_code |

| area_code = [[Area codes 860 and 959|860/959]] |

||

| unemployment_rate = |

| unemployment_rate = |

||

|website |

| website = {{URL|https://newlondonct.org}} |

||

|footnotes |

| footnotes = |

||

|timezone |

| timezone = EST |

||

|utc_offset = −5 |

| utc_offset = −5 |

||

|timezone_DST |

| timezone_DST = EDT |

||

|utc_offset_DST = −4 |

| utc_offset_DST = −4 |

||

|blank_name |

| blank_name = FIPS code |

||

|blank_info |

| blank_info = 09-52280 |

||

|blank1_name |

| blank1_name = GNIS feature ID |

||

|blank1_info |

| blank1_info = 0209237 |

||

|pop_est_as_of = |

| pop_est_as_of = |

||

|pop_est_footnotes = |

| pop_est_footnotes = |

||

|population_est = |

| population_est = |

||

|area_footnotes = <ref name=" |

| area_footnotes = <ref name="CenPopGazetteer2023">{{cite web|title=2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files|url=https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/gazetteer/2023_Gazetteer/2023_gaz_place_09.txt|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=June 14, 2024}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 102: | Line 101: | ||

===Colonial era=== |

===Colonial era=== |

||

The area was called Nameaug by the [[Pequot]] [[Native Americans of the United States|Indians]]. [[John Winthrop, Jr.]] founded the first English settlement here in 1646, making it about the 13th town settled in Connecticut. Inhabitants referred to it informally as Nameaug or as Pequot after the tribe. In the 1650s, the colonists wanted to give the town the official name of London after [[London, England]], but the [[Connecticut General Assembly]] wanted to name it Faire Harbour. The citizens protested, declaring that they would prefer it to be called Nameaug if it could not be officially named London.<ref name="Marrin2007">{{cite book|first=Richard B.|last=Marrin|title=Abstracts from the New London Gazette Covering Southeastern Connecticut, 1763-1769|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y2LanJi-x6MC&pg=PA242 |date= |

The area was called Nameaug by the [[Pequot]] [[Native Americans of the United States|Indians]]. [[John Winthrop, Jr.]] founded the first English settlement here in 1646, making it about the 13th town settled in Connecticut. Inhabitants referred to it informally as Nameaug or as Pequot after the tribe. In the 1650s, the colonists wanted to give the town the official name of London after [[London, England]], but the [[Connecticut General Assembly]] wanted to name it Faire Harbour. The citizens protested, declaring that they would prefer it to be called Nameaug if it could not be officially named London.<ref name="Marrin2007">{{cite book|first=Richard B.|last=Marrin|title=Abstracts from the New London Gazette Covering Southeastern Connecticut, 1763-1769|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y2LanJi-x6MC&pg=PA242 |date=January 1, 2007|publisher=Heritage Books|isbn=978-0-7884-4171-4 |pages=242}}</ref><ref>Frances Manwaring Caulkins, ''History of New London, Connecticut, from the first survey of the coast in 1612 to 1860'', Library of Congress, 1895.</ref> The legislature relented, and the town was officially named New London on March 24, 1658.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Caulkins |first1=Frances Manwaring |last2=Griswold |first2=Cecelia |title=History of New London, Connecticut, from the first survey of the coast in 1612 to 1860 |date=1895 |publisher=New London, H. D. Utley |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofnewlond00caul/page/119/mode/1up |access-date=June 2, 2024|page=119}}</ref> |

||

===American Revolution=== |

===American Revolution=== |

||

The harbor was considered to be the best deep water harbor on [[Long Island Sound]],<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=New London |volume=19 |pages=515–516}}</ref> and consequently New London became a base of [[U.S. Navy|American naval operations]] during the [[American Revolutionary War]] and privateers where it has been said no port took more prizes than New London with between 400–800 being credited to New London privateers including the 1781 taking of supply ship Hannah, the largest prize taken during the war. Famous New Londoners during the American Revolution include [[Nathan Hale]], William Coit, Richard Douglass, Thomas and Nathaniel Shaw, [[Samuel Holden Parsons|Gen. Samuel Parsons]], printer Timothy Green, and Bishop [[Samuel Seabury (bishop)|Samuel Seabury]]. |

The harbor was considered to be the best deep water harbor on [[Long Island Sound]],<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=New London |volume=19 |pages=515–516}}</ref> and consequently New London became a base of [[U.S. Navy|American naval operations]] during the [[American Revolutionary War]] and privateers where it has been said no port took more prizes than New London with between 400–800 being credited to New London privateers including the 1781 taking of supply ship Hannah, the largest prize taken during the war. Famous New Londoners during the American Revolution include [[Nathan Hale]], William Coit, Richard Douglass, Thomas and [[Nathaniel Shaw]], [[Samuel Holden Parsons|Gen. Samuel Parsons]], printer Timothy Green, and Bishop [[Samuel Seabury (bishop)|Samuel Seabury]].{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

||

New London was raided and much of it burned to the ground on September 6, 1781 in the [[Battle of Groton Heights]] by [[Norwich, Connecticut|Norwich]] native [[Benedict Arnold]] in an attempt to destroy the Patriot [[privateer]] fleet and supplies of goods and naval stores within the city. It is often noted that this raid on New London and Groton was intended to divert General [[George Washington]] and the French Army under [[Rochambeau, Jean-Baptiste-Donatien|Rochambeau]] from their march on [[Yorktown, Virginia]]. The main defensive fort for New London was [[Fort Griswold]], located across the Thames River in [[Groton, Connecticut|Groton]]. It was well known to Arnold, who had already informed the British of this so that they could avoid its [[artillery]] fire. British and Hessian troops subsequently attacked and captured New London's [[Fort Trumbull]], while other forces moved in to attack Fort Griswold across the river, then held by Lieutenant-Colonel [[William Ledyard]]. The British suffered great casualties at Fort Griswold before the Americans were finally forced to surrender—whereupon Arnold's men stormed into the fort and slaughtered most of the American troops who defended it, including Ledyard. All told, more than 52 British and 83 American soldiers were killed, and more than 142 British and 39 Americans were wounded, many mortally. New London suffered over 6 defenders killed and 24 wounded, while Arnold's men suffered an equal amount.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.battleofgrotonheights.com |title=The Battle of Groton Heights & Burning of New London |publisher=Battleofgrotonheights.com |date=August 31, 2006 |access-date=October 28, 2011}}</ref> |

New London was raided and much of it burned to the ground on September 6, 1781, in the [[Battle of Groton Heights]] by [[Norwich, Connecticut|Norwich]] native [[Benedict Arnold]] in an attempt to destroy the Patriot [[privateer]] fleet and supplies of goods and naval stores within the city. It is often noted that this raid on New London and Groton was intended to divert General [[George Washington]] and the French Army under [[Rochambeau, Jean-Baptiste-Donatien|Rochambeau]] from their march on [[Yorktown, Virginia]]. The main defensive fort for New London was [[Fort Griswold]], located across the Thames River in [[Groton, Connecticut|Groton]]. It was well known to Arnold, who had already informed the British of this so that they could avoid its [[artillery]] fire. British and Hessian troops subsequently attacked and captured New London's [[Fort Trumbull]], while other forces moved in to attack Fort Griswold across the river, then held by Lieutenant-Colonel [[William Ledyard]]. The British suffered great casualties at Fort Griswold before the Americans were finally forced to surrender—whereupon Arnold's men stormed into the fort and slaughtered most of the American troops who defended it, including Ledyard. All told, more than 52 British and 83 American soldiers were killed, and more than 142 British and 39 Americans were wounded, many mortally. New London suffered over 6 defenders killed and 24 wounded, while Arnold's men suffered an equal amount.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.battleofgrotonheights.com |title=The Battle of Groton Heights & Burning of New London |publisher=Battleofgrotonheights.com |date=August 31, 2006 |access-date=October 28, 2011}}</ref> |

||

Connecticut's independent legislature made New London one of |

Connecticut's independent legislature made New London one of five cities simultaneously brought from ''de facto'' to formalized incorporations in its January session of 1784.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Caulkins |first1=Frances Manwaring |last2=Griswold |first2=Cecelia |title=History of New London, Connecticut, from the first survey of the coast in 1612 to 1860 |date=1895 |publisher=New London, H. D. Utley |page=619 |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofnewlond00caul/page/619/mode/1up}}</ref> |

||

===19th century=== |

===19th century=== |

||

| Line 116: | Line 115: | ||

After the [[War of 1812]] began, the [[Royal Navy]] established a blockade of the [[East Coast of the United States]], including New London. During the war, American forces unsuccessfully attempted to destroy the British ship of the line [[HMS Ramillies (1785)|HMS ''Ramillies'']] while it was lying at anchor in New London's harbor with [[torpedo]]es launched from small boats. This prompted the captain of ''Ramillies'', [[Sir Thomas Hardy, 1st Baronet]], to warn the Americans to cease using this "cruel and unheard-of warfare" or he would "order every house near the shore to be destroyed". The fact that Hardy had been previously so lenient and considerate to the Americans caused them to abandon such attempts with immediate effect.<ref name=Lossing>{{Cite book |last=Lossing |first=Benson |title=The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 |publisher=Harper & Brothers, Publishers |year=1868 |page=692}}</ref>{{rp|693}} |

After the [[War of 1812]] began, the [[Royal Navy]] established a blockade of the [[East Coast of the United States]], including New London. During the war, American forces unsuccessfully attempted to destroy the British ship of the line [[HMS Ramillies (1785)|HMS ''Ramillies'']] while it was lying at anchor in New London's harbor with [[torpedo]]es launched from small boats. This prompted the captain of ''Ramillies'', [[Sir Thomas Hardy, 1st Baronet]], to warn the Americans to cease using this "cruel and unheard-of warfare" or he would "order every house near the shore to be destroyed". The fact that Hardy had been previously so lenient and considerate to the Americans caused them to abandon such attempts with immediate effect.<ref name=Lossing>{{Cite book |last=Lossing |first=Benson |title=The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 |publisher=Harper & Brothers, Publishers |year=1868 |page=692}}</ref>{{rp|693}} |

||

For several decades beginning in the early 19th century, New London was one of the three busiest [[whaling]] ports in the world, along with [[Nantucket]] and [[New Bedford, Massachusetts]]. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The [[New Haven and New London Railroad]] connected New London by rail to New Haven and points beyond by the 1850s. The [[Springfield and New London Railroad]] connected New London to [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], by the 1870s. |

For several decades beginning in the early 19th century, New London was one of the three busiest [[whaling]] ports in the world, along with [[Nantucket]] and [[New Bedford, Massachusetts]]. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The [[New Haven and New London Railroad]] connected New London by rail to New Haven and points beyond by the 1850s. The [[Springfield and New London Railroad]] connected New London to [[Springfield, Massachusetts]], by the 1870s.{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

||

Many distinctive structures built in the 19th century remain, but the [[First Church of Christ (New London, Connecticut)|First Church]] built in 1853 |

Many distinctive structures built in the 19th century remain, but the [[First Church of Christ (New London, Connecticut)|First Church]] built in 1853 collapsed in January 2024. <ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Jacobs |first=Kenneth Franklin |date=2005 |title=Leopold Eidlitz: Becoming an American architect |url=http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1178 |access-date=June 2, 2024 |website=University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons |pages=153–155}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Gendreau |first1=LeAnne |last2=Fortuna |first2=Angela |date=2024-01-26 |title=Historic New London church to be completely demolished after steeple collapse |url=https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/historic-new-london-church-will-need-to-be-demolished-after-steeple-collapse/3203459/ |access-date=June 2, 2024 |website=NBC Connecticut |language=en-US}}</ref> |

||

===Military presence=== |

===Military presence=== |

||

| Line 124: | Line 123: | ||

Several military installations have been part of New London's history, including the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]] and [[Coast Guard Station New London]].<ref>[http://www.uscg.mil/d1/sectlis/units/staNewLondon/ Coast Guard Station New London official web page]</ref> Most of these military installations have been located at [[Fort Trumbull]]. The first Fort Trumbull was an earthwork built 1775–1777 that took part in the [[American Revolutionary War|Revolutionary War]]. The second Fort Trumbull was built 1839–1852 and still stands. By 1910, the fort's defensive function had been superseded by the new forts of the [[Endicott Board|Endicott Program]], primarily located on [[Fishers Island]]. The fort was given to the [[Revenue Cutter Service]] and became the Revenue Cutter Academy. The Revenue Cutter Service was merged into the [[United States Coast Guard]] in 1915, and the Academy relocated to its current site in 1932. During [[World War II]], the [[United States Merchant Marine|Merchant Marine]] Officers Training School was located at Fort Trumbull. From 1950 to 1990, Fort Trumbull was the location for the [[Naval Underwater Sound Laboratory]], which developed [[sonar]] and related systems for [[US Navy]] [[submarine]]s. In 1990, the Sound Laboratory was merged with the [[Naval Underwater Systems Center]] in [[Newport, Rhode Island]], and the New London facility was closed in 1996.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20091026194651/http://www.geocities.com/~jmgould/trumhist.html The History of Fort Trumbull by John Duchesneau]</ref><ref>[http://www.fortfriends.org/history.htm Fort Trumbull History Site]</ref> |

Several military installations have been part of New London's history, including the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]] and [[Coast Guard Station New London]].<ref>[http://www.uscg.mil/d1/sectlis/units/staNewLondon/ Coast Guard Station New London official web page]</ref> Most of these military installations have been located at [[Fort Trumbull]]. The first Fort Trumbull was an earthwork built 1775–1777 that took part in the [[American Revolutionary War|Revolutionary War]]. The second Fort Trumbull was built 1839–1852 and still stands. By 1910, the fort's defensive function had been superseded by the new forts of the [[Endicott Board|Endicott Program]], primarily located on [[Fishers Island]]. The fort was given to the [[Revenue Cutter Service]] and became the Revenue Cutter Academy. The Revenue Cutter Service was merged into the [[United States Coast Guard]] in 1915, and the Academy relocated to its current site in 1932. During [[World War II]], the [[United States Merchant Marine|Merchant Marine]] Officers Training School was located at Fort Trumbull. From 1950 to 1990, Fort Trumbull was the location for the [[Naval Underwater Sound Laboratory]], which developed [[sonar]] and related systems for [[US Navy]] [[submarine]]s. In 1990, the Sound Laboratory was merged with the [[Naval Underwater Systems Center]] in [[Newport, Rhode Island]], and the New London facility was closed in 1996.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20091026194651/http://www.geocities.com/~jmgould/trumhist.html The History of Fort Trumbull by John Duchesneau]</ref><ref>[http://www.fortfriends.org/history.htm Fort Trumbull History Site]</ref> |

||

The [[Naval Submarine Base New London]] is physically located in Groton, but submarines were stationed in New London during World War II and from 1951 to 1991. The [[submarine tender]] [[USS Fulton (AS-11)|''Fulton'']] and [[Submarine Squadron 10]] were based at State Pier in New London during this time. Squadron Ten was usually composed of eight to ten submarines and was the first all-nuclear submarine squadron. USS ''Fulton'' was decommissioned, after 50 years of service, in 1991 and Submarine Squadron 10 was disbanded at the same time. In the 1990s, State Pier was rebuilt as a [[freight container|container]] terminal. |

The [[Naval Submarine Base New London]] is physically located in Groton, but submarines were stationed in New London during World War II and from 1951 to 1991. The [[submarine tender]] [[USS Fulton (AS-11)|''Fulton'']] and [[Submarine Squadron 10]] were based at State Pier in New London during this time. Squadron Ten was usually composed of eight to ten submarines and was the first all-nuclear submarine squadron. USS ''Fulton'' was decommissioned, after 50 years of service, in 1991 and Submarine Squadron 10 was disbanded at the same time. In the 1990s, State Pier was rebuilt as a [[freight container|container]] terminal.{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

||

During the [[Red Summer]] of 1919, there were [[New London riots of 1919|a series of racial riots]] between white and black Navy men stationed in New London and Groton.{{sfn|Rucker|Upton|2007|p=554}}{{sfn|The Greeneville Daily Sun|1919|p=1}}{{sfn|Voogd|2008|p=95}} |

During the [[Red Summer]] of 1919, there were [[New London riots of 1919|a series of racial riots]] between white and black Navy men stationed in New London and Groton.{{sfn|Rucker|Upton|2007|p=554}}{{sfn|The Greeneville Daily Sun|1919|p=1}}{{sfn|Voogd|2008|p=95}} |

||

| Line 133: | Line 132: | ||

[[Image:Fort Trumbull three.jpg|right|thumb|One of the few remaining houses in the Fort Trumbull neighborhood, June 10, 2007]] |

[[Image:Fort Trumbull three.jpg|right|thumb|One of the few remaining houses in the Fort Trumbull neighborhood, June 10, 2007]] |

||

The neighborhood of Fort Trumbull once consisted of nearly two-dozen homes, but they were seized by the City of New London using [[eminent domain]]. This measure was supported in a 5–4 ruling in the 2005 Supreme Court case ''[[Kelo v. City of New London]]'', and the homes were ultimately demolished by the city as part of an economic development plan. The site was slated to be redeveloped under this plan, but the chosen developer was not able to get financing and the project failed. The empty landscape of the Fort Trumbull area has been widely characterized as an example of government overreach and inefficiency.<ref name=jacoby>{{cite news|url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/03/12/the-devastation-caused-eminent-domain-abuse/yWsy0MNEZ91TM94PYQIh0L/story.html |last=Jacoby|first= Jeff |title= Eminent disaster: Homeowners in Connecticut town were dispossessed for nothing|work=[[The Boston Globe]]|date=March 12, 2014}}</ref><ref name=WeekStand>{{cite news|last1=Allen|first1=Charlotte |title='Kelo' Revisited|url=http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/kelo-revisited_776021.html# |access-date= |

The neighborhood of Fort Trumbull once consisted of nearly two-dozen homes, but they were seized by the City of New London using [[eminent domain]]. This measure was supported in a 5–4 ruling in the 2005 Supreme Court case ''[[Kelo v. City of New London]]'', and the homes were ultimately demolished by the city as part of an economic development plan. The site was slated to be redeveloped under this plan, but the chosen developer was not able to get financing and the project failed. The empty landscape of the Fort Trumbull area has been widely characterized as an example of government overreach and inefficiency.<ref name=jacoby>{{cite news|url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/03/12/the-devastation-caused-eminent-domain-abuse/yWsy0MNEZ91TM94PYQIh0L/story.html |last=Jacoby|first= Jeff |title= Eminent disaster: Homeowners in Connecticut town were dispossessed for nothing|work=[[The Boston Globe]]|date=March 12, 2014}}</ref><ref name=WeekStand>{{cite news|last1=Allen|first1=Charlotte |title='Kelo' Revisited|url=http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/kelo-revisited_776021.html# |access-date=October 23, 2014|work=Weekly Standard|date=February 10, 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Somin|first=Ilya|url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2015/05/29/the-story-behind-the-kelo-case-how-an-obscure-takings-case-came-to-shock-the-conscience-of-the-nation/ |title= The story behind Kelo v. City of New London – how an obscure takings case got to the Supreme Court and shocked the nation|newspaper= [[The Washington Post]]|date=May 29, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Downey |first=Kirstin |url= http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2002283981_scotus22.html |title=Nation & World | Supreme Court ruling due on use of eminent domain |work=Seattle Times |access-date=October 28, 2011 |date=May 22, 2005}}</ref> |

||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

| Line 148: | Line 147: | ||

*Ocean Beach |

*Ocean Beach |

||

Other minor communities and geographic features include Bates Woods Park, Fort Trumbull, Glenwood Park, Green's Harbor Beach, Mitchell's Woods, Pequot Colony, Riverside Park, Old Town Mill. |

Other minor communities and geographic features include Bates Woods Park, Fort Trumbull, Glenwood Park, Green's Harbor Beach, Mitchell's Woods, Pequot Colony, Riverside Park, Old Town Mill.{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

||

===Towns created from New London=== |

===Towns created from New London=== |

||

| Line 208: | Line 207: | ||

==Demographics== |

==Demographics== |

||

[[File:New London Population.png|thumb|left|Population since 1810]] |

|||

{{See also|List of Connecticut locations by per capita income}} |

{{See also|List of Connecticut locations by per capita income}} |

||

| Line 214: | Line 212: | ||

According to the 2006–2008 [[American Community Survey]], non-Hispanic [[White American|whites]] made up 54.6% of New London's population. Non-Hispanic [[Black American|blacks]] made up 14.0% of the population. [[Asian American|Asians]] of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.6% of the city's population. [[Multiracial American|Multiracial]] individuals of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.3% of the population; people of mixed black and white ancestry made up 1.7% of the population. In addition, people of mixed black and Native American ancestry made up 1.0% of the population. People of mixed white and Native American ancestry made up 0.7% of the population; those of mixed white and Asian ancestry made up 0.4% of the populace. [[Hispanic and Latino Americans|Hispanics and Latinos]] made up 21.9% of the population, of which 13.8% were [[Puerto Ricans in the United States|Puerto Rican]].<ref>{{cite web |work=American FactFinder |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR5&-ds_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-_sse=on |title=New London city, Connecticut – ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006–2008 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=October 28, 2011 |archive-url= https://archive.today/20200211183117/http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR5&-ds_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-_sse=on |archive-date=February 11, 2020 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

According to the 2006–2008 [[American Community Survey]], non-Hispanic [[White American|whites]] made up 54.6% of New London's population. Non-Hispanic [[Black American|blacks]] made up 14.0% of the population. [[Asian American|Asians]] of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.6% of the city's population. [[Multiracial American|Multiracial]] individuals of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.3% of the population; people of mixed black and white ancestry made up 1.7% of the population. In addition, people of mixed black and Native American ancestry made up 1.0% of the population. People of mixed white and Native American ancestry made up 0.7% of the population; those of mixed white and Asian ancestry made up 0.4% of the populace. [[Hispanic and Latino Americans|Hispanics and Latinos]] made up 21.9% of the population, of which 13.8% were [[Puerto Ricans in the United States|Puerto Rican]].<ref>{{cite web |work=American FactFinder |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR5&-ds_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-_sse=on |title=New London city, Connecticut – ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006–2008 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=October 28, 2011 |archive-url= https://archive.today/20200211183117/http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR5&-ds_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-_sse=on |archive-date=February 11, 2020 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

The top five largest [[European American|European]] |

The top five largest [[European American|European]] ancestral ethnicities were [[Italian American|Italian]] (10.5%), [[Irish American|Irish]] (9.7%), [[German American|German]] (7.4%), [[English American|English]] (6.8%), and [[Polish American|Polish]] (5.0%) |

||

According to the survey, 74.4% of people over the age of 5 spoke only English at home. Approximately 16.0% of the population spoke Spanish at home.<ref>{{cite web |work=American FactFinder |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR2&-ds_name=&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false |title=New London city, Connecticut – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2006–2008 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=October 28, 2011 |archive-url= https://archive.today/20200211183356/http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR2&-ds_name=&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false |archive-date=February 11, 2020 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

According to the survey, 74.4% of people over the age of 5 spoke only English at home. Approximately 16.0% of the population spoke Spanish at home.<ref>{{cite web |work=American FactFinder |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR2&-ds_name=&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false |title=New London city, Connecticut – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2006–2008 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=October 28, 2011 |archive-url= https://archive.today/20200211183356/http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0952280&-qr_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_DP3YR2&-ds_name=&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false |archive-date=February 11, 2020 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

In 2012, the population reached 27,700. The median household income was $44,100, with 20% of the population below the poverty line. |

|||

| ⚫ | As of the census<ref name="GR2">{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/profile/New_London_city,_Connecticut?g=160XX00US0952280 |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= New London city, Connecticut Census Bureau Profile}}</ref><ref name="GR3">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/newlondoncityconnecticut|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts for New London city, Connecticut}}</ref> of 2020, there were 27,374 people and 11,125 households. The population density was {{convert|4,868.7|/sqmi|/km2}}. There were 12,119 housing units at an average density of {{convert|2156.4|/sqmi|/km2}}. The racial makeup of the city was 56.2% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 29.4% [[Hispanic (U.S. Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Latino (U.S. Census)|Latino]] of any race, 17.0% [[African American (U.S. Census)|African American]], 0.3% [[Native American (U.S. Census)|Native American]], 2.3% [[Asian (U.S. Census)|Asian]], 0.0% [[Pacific Islander (U.S. Census)|Pacific Islander]], 16.7% from [[Race (United States Census)|other races]], and 10.8% from two or more races. |

||

| ⚫ | There were 11,125 households, out of which 23.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.4% were married couples living together, 34.1% had a female householder with no partner present, and 27.8% had a male householder with no partner present. 14.7% of households had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.12 and the average family size was 2.84.<ref name="GR4">{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDP5Y2022.DP02?g=160XX00US0952280|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= Selected Social Characteristics in the United States for New London city, Connecticut}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | As of the census<ref name="GR2">{{cite web|url=https:// |

||

| ⚫ | In the city, the population was spread out, with 16.5% under the age of 18, 19.4% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 22.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males.<ref name="GR5">{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2022.S0101?g=160XX00US0952280&tid=ACSST5Y2022.S0101|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= Age and Sex for New London city, Connecticut}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | There were |

||

The median income for a household in the city was $56,237, and the median income for a family was $65,357.<ref name="GR6">{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2022.S1901?g=160XX00US0952280|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars) for New London city, Connecticut}}</ref> About 21.5% of the population was below the poverty line, including 36.4% of those under age 18 and 11.1% of those age 65 or over.<ref name="GR7">{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2022.S1701?g=160XX00US0952280|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=May 31, 2024 |title= Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months for New London city, Connecticut}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In the city, the population was spread out, with |

||

==Economy== |

|||

The median income for a household in the city was $33,809, and the median income for a family was $38,942. Males had a median income of $31,405 versus $25,426 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,437. About 13.4% of families and 15.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.5% of those under age 18 and 11.4% of those age 65 or over. |

|||

| ⚫ | New London was one of the world's three busiest [[whaling]] ports for several decades beginning in the early 19th century, along with [[Nantucket]] and [[New Bedford, Massachusetts]]. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The city subsequently became home to other shipping and manufacturing industries, but had gradually lost most of its industrial heart. The State Pier (south of the [[Gold Star Memorial Bridge]]) is being converted to support some of the [[Offshore wind power in the United States#Wind ports and infrastructure|offshore wind power in the United States]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Memija |first1=Adnan |title=New London State Pier Terminal Getting Ready for South Fork Wind Project |url=https://www.offshorewind.biz/2023/03/06/new-london-state-pier-terminal-getting-ready-for-south-fork-wind-project/ |website=Offshore Wind |date=March 6, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=New London Terminal Overview |url=https://gatewayt.com/new-london-terminal-overview |website=Gateway Terminal}}</ref> |

||

==Arts and culture== |

==Arts and culture== |

||

| Line 237: | Line 236: | ||

===Music=== |

===Music=== |

||

Notable artists and ensembles include: |

Notable artists and ensembles include: |

||

* Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1946 and led by [[Toshiyuki Shimada]], who is also conductor of the [[Yale Symphony Orchestra]] in New Haven. |

* [[Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra]], founded in 1946 and led by [[Toshiyuki Shimada]], who is also conductor of the [[Yale Symphony Orchestra]] in New Haven. |

||

* [[The Idlers]] of the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]], an all-male vocal group specializing in [[sea shanty|sea shanties]] and patriotic music. |

* [[The Idlers]] of the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]], an all-male vocal group specializing in [[sea shanty|sea shanties]] and patriotic music. |

||

* [[Service bands#Coast Guard Band|United States Coast Guard Band]], founded in 1925 with the assistance of [[John Philip Sousa]]. Stationed at the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]] and attracting talented musicians from all parts of the country, the band is the official musical representative of [[United States Coast Guard#History|the nation's oldest continuous seagoing service]]. |

* [[Service bands#Coast Guard Band|United States Coast Guard Band]], founded in 1925 with the assistance of [[John Philip Sousa]]. Stationed at the [[United States Coast Guard Academy]] and attracting talented musicians from all parts of the country, the band is the official musical representative of [[United States Coast Guard#History|the nation's oldest continuous seagoing service]]. |

||

* [[The Can Kickers]], a [[folk punk]] band. |

* [[The Can Kickers]], a [[folk punk]] band. |

||

===Literature=== |

|||

In her Scenes in My Native Land, 1845, [[Lydia Sigourney]] includes the poem [[wikisource:Scenes in my Native Land/Sunrise at New London|Sunrise at New London]] with descriptive passages relating to the district. <ref>{{cite web| last =Sigourney|first=Lydia|title=Scenes in My Native Land| url=https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=KjsCAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PA84| year=1845 |publisher=Thurston, Torry & Co.}}</ref> |

|||

===Sites of interest=== |

===Sites of interest=== |

||

| Line 266: | Line 268: | ||

* [[Winthrop Mill]] (1650) |

* [[Winthrop Mill]] (1650) |

||

* Former Second Congregational Church (1870)<ref>{{cite book|last1=Morrison|first1=Betty Urban|title=The Church on the Hill: A history of the Second Congregational Church, New London, Connecticut 1835-1985|date=1985|publisher=Second Congregational Church|location=New London, Connecticut|page=17<!--|access-date=29 December 2014-->}}</ref> |

* Former Second Congregational Church (1870)<ref>{{cite book|last1=Morrison|first1=Betty Urban|title=The Church on the Hill: A history of the Second Congregational Church, New London, Connecticut 1835-1985|date=1985|publisher=Second Congregational Church|location=New London, Connecticut|page=17<!--|access-date=29 December 2014-->}}</ref> |

||

* The Pequot Chapel (1872)<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ochsner |first1=Jeffrey Karl |title=H. H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works |date=1984 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-0-262-65015-1 |page=30 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gBDXfLHsnc4C&pg=PA30 |access-date=June 3, 2024 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

* The Pequot Chapel (1872) |

|||

==Government== |

==Government== |

||

[[File:Municipal Building New London from west.jpg|thumb|right|Municipal Building on State Street in New London (2013)]] |

[[File:Municipal Building New London from west.jpg|thumb|right|Municipal Building on State Street in New London (2013)]] |

||

In 2010, New London changed their form of government from council-manager to strong mayor-council after a charter revision.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-08/news/hc-new-london-finizio-1105-20111105_1_revision-six-candidates-charter |title=New Face Stirs Up Historic New London Election|work=tribunedigital-thecourant |access-date= |

In 2010, New London changed their form of government from council-manager to strong mayor-council after a charter revision.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-08/news/hc-new-london-finizio-1105-20111105_1_revision-six-candidates-charter |title=New Face Stirs Up Historic New London Election|work=tribunedigital-thecourant |access-date=November 21, 2017|language=en}}</ref> Distinct town and city government structures formerly existed and technically continue; however, they now govern exactly the same territory and have elections on the same ballot on [[Election Day (United States)|Election Day]] in November.{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

||

==Infrastructure== |

==Infrastructure== |

||

===Industry=== |

|||

| ⚫ | New London was one of the world's three busiest [[whaling]] ports for several decades beginning in the early 19th century, along with [[Nantucket]] and [[New Bedford, Massachusetts]]. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The city subsequently became home to other shipping and manufacturing industries, but had gradually lost most of its industrial heart. The State Pier (south of the [[Gold Star Memorial Bridge]]) is being converted to support some of the [[Offshore wind power in the United States#Wind ports and infrastructure|offshore wind power in the United States]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Memija |first1=Adnan |title=New London State Pier Terminal Getting Ready for South Fork Wind Project |url=https://www.offshorewind.biz/2023/03/06/new-london-state-pier-terminal-getting-ready-for-south-fork-wind-project/ |website=Offshore Wind |date= |

||

===Transportation=== |

===Transportation=== |

||

[[File:New London Union Station.JPG|thumb|right|[[New London Union Station]], designed by H.H. Richardson]] |

[[File:New London Union Station.JPG|thumb|right|[[New London Union Station]], designed by H.H. Richardson]] |

||

Bus service includes regional [[Southeast Area Transit]] buses, [[Estuary Transit District]] buses, and interstate [[Greyhound Lines]] buses. [[Interstate 95 in Connecticut|Interstate 95]] passes through New London. |

|||

[[New London Union Station]] is served by Amtrak's ''[[Northeast Regional]]'' and ''[[Acela]]'' regional rail services, and [[Shore Line East]] commuter rail service. The [[Providence and Worcester Railroad]] and [[New England Central Railroad]] handle freight. |

|||

Ferries include [[Cross Sound Ferry]] to [[Long Island]], [[Fishers Island]], and [[Block Island]]. New London is also visited by cruise ships.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Howard |first1=Lee |title=Cruise ships returning to New London |url=https://www.theday.com/article/20130907/BIZ02/309079965 |access-date=August 28, 2018 |work=The Day |date=September 7, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Groton-New London Airport]], a [[general aviation]] facility, is located in [[Groton, Connecticut|Groton]]. Scheduled commercial flights are available at [[T. F. Green Airport |

The [[Groton-New London Airport]], a [[general aviation]] facility, is located in [[Groton, Connecticut|Groton]]. Scheduled commercial flights are available at [[T. F. Green Airport]] and [[Tweed New Haven Regional Airport]]. |

||

==Mayors of New London== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Ernest E. Rogers]] (1915–1918)<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Notable people== |

==Notable people== |

||

[[File:Harry-K-Daghlian.gif|thumb|right|upright|Harry Daghlian, a New London native who was the first person to die as the result of a radioactive [[criticality accident]]. A small memorial to Daghlian sits in a New London park.]] |

|||

<!-- Please ALPHABETIZE by LAST NAMES in list --> |

<!-- Please ALPHABETIZE by LAST NAMES in list --> |

||

[[File:A. J. Dillon (51631649396) (cropped).jpg|thumb|180px|[[A. J. Dillon]]]] |

|||

[[File:Nathan-hale-cityhall.jpg|thumb|180px|[[Nathan Hale]]]] |

|||

[[File:John McCain official portrait 2009.jpg|thumb|180px|[[John McCain]]]] |

|||

[[File:ONeill-Eugene-LOC.jpg|thumb|180px|[[Eugene O'Neill]]]] |

|||

{{div col}} |

{{div col}} |

||

* [[Eliphalet Adams]] (1677–1753), clergyman |

* [[Eliphalet Adams]] (1677–1753), clergyman |

||

| Line 312: | Line 298: | ||

* [[James Avery (American colonist)|James Avery]] (1620–1700), politician and military commander |

* [[James Avery (American colonist)|James Avery]] (1620–1700), politician and military commander |

||

* [[Valerie Azlynn]] (born 1980), actress |

* [[Valerie Azlynn]] (born 1980), actress |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Nathan Belcher]] (1813–1891), congressman |

* [[Nathan Belcher]] (1813–1891), congressman |

||

* [[James M. Bell (U.S. Army brigadier general)|James M. Bell]] (1837–1919), U.S. Army brigadier general, retired to New London<ref name="Express">{{cite news |date=September 17, 1919 |title=Gen. J. M. Bell Is Dead |url=https://www.newspapers.com/article/los-angeles-evening-express-jmbell/143257105/ |work=Los Angeles Evening Express |location=Los Angeles, CA |page=10 |via=[[Newspapers.com]]}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Augustus Brandegee]] (1828–1904), judge, congressman, abolitionist |

* [[Augustus Brandegee]] (1828–1904), judge, congressman, abolitionist |

||

* [[Frank B. Brandegee]] (1864–1924), congressman and senator |

* [[Frank B. Brandegee]] (1864–1924), congressman and senator |

||

| Line 321: | Line 307: | ||

* [[Daniel Burrows]] (1756–1858), congressman |

* [[Daniel Burrows]] (1756–1858), congressman |

||

* [[John Button (soldier)]] (1772–1861), American-born Upper Canada settler (founder of [[Buttonville, Ontario]]), sedentary [[Canadian militia]] officer and founder of the 1st York Light Dragoons |

* [[John Button (soldier)]] (1772–1861), American-born Upper Canada settler (founder of [[Buttonville, Ontario]]), sedentary [[Canadian militia]] officer and founder of the 1st York Light Dragoons |

||

* [[William Colfax]], soldier and settler |

* [[William Colfax]] (1756-1838), soldier and settler |

||

* [[Frances Manwaring Caulkins]] (1795–1869), historian, genealogist, author |

* [[Frances Manwaring Caulkins]] (1795–1869), historian, genealogist, author |

||

* [[Thomas Humphrey Cushing]] (1755–1822), brigadier general in the War of 1812 and collector of customs |

* [[Thomas Humphrey Cushing]] (1755–1822), brigadier general in the War of 1812 and collector of customs |

||

* [[John M. K. Davis]], U.S. Army brigadier general; lived in New London during his retirement<ref>{{cite news |date=December 28, 1917 |title=Mrs. John H. K. Davis |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/105790193/mrs-davis/ |work=[[Hartford Courant]] |location=Hartford, CT |page=8 |via=[[Newspapers.com]]}}</ref> |

* [[John M. K. Davis]] (1844-1920), U.S. Army brigadier general; lived in New London during his retirement<ref>{{cite news |date=December 28, 1917 |title=Mrs. John H. K. Davis |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/105790193/mrs-davis/ |work=[[Hartford Courant]] |location=Hartford, CT |page=8 |via=[[Newspapers.com]]}}</ref> |

||

* [[Harry Daghlian]] (1921–1945), physicist at [[Los Alamos National Lab]], first person to die as a result of a criticality accident |

* [[Harry Daghlian]] (1921–1945), physicist at [[Los Alamos National Lab]], first person to die as a result of a criticality accident |

||

* [[A. J. Dillon]] (born 1998), [[American football]] [[running back]] |

* [[A. J. Dillon]] (born 1998), [[American football]] [[running back]] |

||

| Line 350: | Line 336: | ||

* [[Bryan F. Mahan]] (1856–1923), congressman |

* [[Bryan F. Mahan]] (1856–1923), congressman |

||

* [[Richard Mansfield]] (1857–1907), actor |

* [[Richard Mansfield]] (1857–1907), actor |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[John McCain]] (1936–2018), senator and [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] presidential nominee (lived in New London as a child when his father, [[John S. McCain, Jr.]], worked at the naval submarine base) |

* [[John McCain]] (1936–2018), senator and [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] presidential nominee (lived in New London as a child when his father, [[John S. McCain, Jr.]], worked at the naval submarine base) |

||

* [[Lansing McVickar]] (1895–1945), career officer with the United States Army |

* [[Lansing McVickar]] (1895–1945), career officer with the United States Army |

||

| Line 377: | Line 364: | ||

* [[Sigmund Strochlitz]] (1916–2006), activist and Holocaust survivor |

* [[Sigmund Strochlitz]] (1916–2006), activist and Holocaust survivor |

||

* [[Dana Suesse]] (1909–1987), composer, songwriter, musician |

* [[Dana Suesse]] (1909–1987), composer, songwriter, musician |

||

* [[Ron Suresha]], author and editor |

* [[Ron Suresha]] (born 1958), author and editor |

||

* [[Flora M. Vare]], (1874–1962), Pennsylvania State Senator from 1925 to 1928 |

* [[Flora M. Vare]], (1874–1962), Pennsylvania State Senator from 1925 to 1928 |

||

* [[Cassie Ventura]] (born 1986), singer |

* [[Cassie Ventura]] (born 1986), singer |

||

| Line 388: | Line 375: | ||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

== |

==Mayors of New London== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[National Register of Historic Places in New London County, Connecticut]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

'''Notes''' |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

'''Bibliography''' |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{cite news |date= May 31, 1919|title= Race Riot at New London Naval Base|last=The Greeneville Daily Sun |url=https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn97065122/1919-05-31/ed-1/seq-1/# |newspaper= The Greeneville Daily Sun |publisher=W.R. Lyon|location=[[Greeneville, Tennessee]]|issn=2475-0174|oclc=37307396 |pages=1–4|access-date= July 19, 2019 }} |

*{{cite news |date= May 31, 1919|title= Race Riot at New London Naval Base|last=The Greeneville Daily Sun |url=https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn97065122/1919-05-31/ed-1/seq-1/# |newspaper= The Greeneville Daily Sun |publisher=W.R. Lyon|location=[[Greeneville, Tennessee]]|issn=2475-0174|oclc=37307396 |pages=1–4|access-date= July 19, 2019 }} |

||

*{{cite book |last1=Rucker|first1=Walter C. |last2=Upton|first2=James N. | title = Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 2|year=2007| publisher = [[Greenwood Publishing Group]]| isbn=9780313333026}} |

*{{cite book |last1=Rucker|first1=Walter C. |last2=Upton|first2=James N. | title = Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 2|year=2007| publisher = [[Greenwood Publishing Group]]| isbn=9780313333026}} Total pages: 930 |

||

*{{cite book |last=Voogd|first=Jan | title = Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919|year=2008| publisher = Peter Lang| isbn= 9781433100673}} |

*{{cite book |last=Voogd|first=Jan | title = Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919|year=2008| publisher = Peter Lang| isbn= 9781433100673}} Total pages: 234 |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

| Line 411: | Line 408: | ||

{{New London County, Connecticut}} |

{{New London County, Connecticut}} |

||

{{Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region, Connecticut}} |

{{Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region, Connecticut}} |

||

{{New England}} |

|||

{{Connecticut county seats}} |

{{Connecticut county seats}} |

||

{{authority control}} |

{{authority control}} |

||

Revision as of 22:07, 12 July 2024

New London | |

|---|---|

| City of New London | |

New London skyline from Fort Griswold | |

| Nickname: The Whaling City | |

| Motto: | |

| Coordinates: 41°21′20″N 72°05′58″W / 41.35556°N 72.09944°W | |

| Land | Vereinigte Staaten |

| U.S. state | Connecticut |

| County | New London |

| Region | Southeastern CT |

| Settled | 1646 (Pequot Plantation) |

| Named | 1658 (New London) |

| Incorporated (city) | 1784 |

| Named for | London, England |

| Regierung | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Michael E. Passero

City Council |

| Area | |

| • City | 10.60 sq mi (27.43 km2) |

| • Land | 5.61 sq mi (14.52 km2) |

| • Water | 4.98 sq mi (12.91 km2) |

| • Urban | 123.03 sq mi (318.66 km2) |

| Elevation | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 27,367 |

| • Density | 4,868/sq mi (1,879.6/km2) |

| • Metro | 274,055 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 06320 |

| Area code(s) | 860/959 |

| FIPS code | 09-52280 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0209237 |

| Website | newlondonct |

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. The city is part of the Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region.

New London is home to the United States Coast Guard Academy, Connecticut College, Mitchell College, and The Williams School. The Coast Guard Station New London and New London Harbor is home port to the Coast Guard Cutter Coho and the Coast Guard's tall ship Eagle. The city had a population of 27,367 at the 2020 census.[4] The Norwich–New London metropolitan area includes 21 towns and 274,055 people.

History

Colonial era

The area was called Nameaug by the Pequot Indians. John Winthrop, Jr. founded the first English settlement here in 1646, making it about the 13th town settled in Connecticut. Inhabitants referred to it informally as Nameaug or as Pequot after the tribe. In the 1650s, the colonists wanted to give the town the official name of London after London, England, but the Connecticut General Assembly wanted to name it Faire Harbour. The citizens protested, declaring that they would prefer it to be called Nameaug if it could not be officially named London.[5][6] The legislature relented, and the town was officially named New London on March 24, 1658.[7]

American Revolution

The harbor was considered to be the best deep water harbor on Long Island Sound,[8] and consequently New London became a base of American naval operations during the American Revolutionary War and privateers where it has been said no port took more prizes than New London with between 400–800 being credited to New London privateers including the 1781 taking of supply ship Hannah, the largest prize taken during the war. Famous New Londoners during the American Revolution include Nathan Hale, William Coit, Richard Douglass, Thomas and Nathaniel Shaw, Gen. Samuel Parsons, printer Timothy Green, and Bishop Samuel Seabury.[citation needed]

New London was raided and much of it burned to the ground on September 6, 1781, in the Battle of Groton Heights by Norwich native Benedict Arnold in an attempt to destroy the Patriot privateer fleet and supplies of goods and naval stores within the city. It is often noted that this raid on New London and Groton was intended to divert General George Washington and the French Army under Rochambeau from their march on Yorktown, Virginia. The main defensive fort for New London was Fort Griswold, located across the Thames River in Groton. It was well known to Arnold, who had already informed the British of this so that they could avoid its artillery fire. British and Hessian troops subsequently attacked and captured New London's Fort Trumbull, while other forces moved in to attack Fort Griswold across the river, then held by Lieutenant-Colonel William Ledyard. The British suffered great casualties at Fort Griswold before the Americans were finally forced to surrender—whereupon Arnold's men stormed into the fort and slaughtered most of the American troops who defended it, including Ledyard. All told, more than 52 British and 83 American soldiers were killed, and more than 142 British and 39 Americans were wounded, many mortally. New London suffered over 6 defenders killed and 24 wounded, while Arnold's men suffered an equal amount.[9]

Connecticut's independent legislature made New London one of five cities simultaneously brought from de facto to formalized incorporations in its January session of 1784.[10]

19th century

After the War of 1812 began, the Royal Navy established a blockade of the East Coast of the United States, including New London. During the war, American forces unsuccessfully attempted to destroy the British ship of the line HMS Ramillies while it was lying at anchor in New London's harbor with torpedoes launched from small boats. This prompted the captain of Ramillies, Sir Thomas Hardy, 1st Baronet, to warn the Americans to cease using this "cruel and unheard-of warfare" or he would "order every house near the shore to be destroyed". The fact that Hardy had been previously so lenient and considerate to the Americans caused them to abandon such attempts with immediate effect.[11]: 693

For several decades beginning in the early 19th century, New London was one of the three busiest whaling ports in the world, along with Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The New Haven and New London Railroad connected New London by rail to New Haven and points beyond by the 1850s. The Springfield and New London Railroad connected New London to Springfield, Massachusetts, by the 1870s.[citation needed]

Many distinctive structures built in the 19th century remain, but the First Church built in 1853 collapsed in January 2024. [12][13]

Military presence

Several military installations have been part of New London's history, including the United States Coast Guard Academy and Coast Guard Station New London.[14] Most of these military installations have been located at Fort Trumbull. The first Fort Trumbull was an earthwork built 1775–1777 that took part in the Revolutionary War. The second Fort Trumbull was built 1839–1852 and still stands. By 1910, the fort's defensive function had been superseded by the new forts of the Endicott Program, primarily located on Fishers Island. The fort was given to the Revenue Cutter Service and became the Revenue Cutter Academy. The Revenue Cutter Service was merged into the United States Coast Guard in 1915, and the Academy relocated to its current site in 1932. During World War II, the Merchant Marine Officers Training School was located at Fort Trumbull. From 1950 to 1990, Fort Trumbull was the location for the Naval Underwater Sound Laboratory, which developed sonar and related systems for US Navy submarines. In 1990, the Sound Laboratory was merged with the Naval Underwater Systems Center in Newport, Rhode Island, and the New London facility was closed in 1996.[15][16]

The Naval Submarine Base New London is physically located in Groton, but submarines were stationed in New London during World War II and from 1951 to 1991. The submarine tender Fulton and Submarine Squadron 10 were based at State Pier in New London during this time. Squadron Ten was usually composed of eight to ten submarines and was the first all-nuclear submarine squadron. USS Fulton was decommissioned, after 50 years of service, in 1991 and Submarine Squadron 10 was disbanded at the same time. In the 1990s, State Pier was rebuilt as a container terminal.[citation needed]

During the Red Summer of 1919, there were a series of racial riots between white and black Navy men stationed in New London and Groton.[17][18][19]

Fort Trumbull

The neighborhood of Fort Trumbull once consisted of nearly two-dozen homes, but they were seized by the City of New London using eminent domain. This measure was supported in a 5–4 ruling in the 2005 Supreme Court case Kelo v. City of New London, and the homes were ultimately demolished by the city as part of an economic development plan. The site was slated to be redeveloped under this plan, but the chosen developer was not able to get financing and the project failed. The empty landscape of the Fort Trumbull area has been widely characterized as an example of government overreach and inefficiency.[20][21][22][23]

Geography

In terms of land area, New London is one of the smallest cities in Connecticut. Of the whole 10.76 square miles (27.9 km2), nearly half is water; 5.54 square miles (14.3 km2) is land.[24]

The town and city of New London are coextensive. Sections of the original town were ceded to form newer towns between 1705 and 1801. The towns of Groton, Ledyard, Montville, and Waterford, and portions of Salem and East Lyme, now occupy what had earlier been the outlying area of New London.[25]

New London is bounded on the west and north by the town of Waterford on the east by the Thames River and Groton and on the south by Long Island Sound.

Principal communities

- Downtown New London

- Ocean Beach

Other minor communities and geographic features include Bates Woods Park, Fort Trumbull, Glenwood Park, Green's Harbor Beach, Mitchell's Woods, Pequot Colony, Riverside Park, Old Town Mill.[citation needed]

Towns created from New London

New London originally had a larger land area when it was established. Towns set off since include:

- Stonington in 1649

- This large area ran from the Mystic River to the Pawcatuck River, including Pawcatuck, Wequetequock, and the easterly half of Mystic. It stretched inland from Long Island Sound to Lantern Hill.

- North Stonington was created from the northern half of Stonington in 1807.

- Groton in 1705

- Ledyard (originally North Groton) created from a part of Groton in 1836.

- Montville in 1786.

- Salem created from parts of Montville, Colchester, and Lyme in 1819

- Waterford in 1801.

- East Lyme created from parts of Waterford and Lyme in 1839.

- Fishers Island officially left Connecticut and became part of New York in 1879.

Climate

Using the Köppen climate classification New London has a warm temperate climate. This zone is defined as having a monthly mean temperature above 26.4 °F (−3 C) but below 64.4 °F (18 C) in the coldest month.

The city experiences long, hot and humid summers, and cool to cold winters with snowfall on occasion. The city averages 2,300 hours of sunshine annually (higher than the USA average). New London lies in the broad transition zone between continental climates to the north in New England and southern Canada, and the humid subtropical climates to the south along the lower East Coast.

From May to late September, the southerly flow from the Bermuda High creates hot and humid tropical weather conditions. Daytime heating produces occasional thunderstorms with heavy but brief downpours. Daytime highs in summer are normally near 80 °F, with occasional heat waves bringing high temperatures into the 90's °F. Spring and Fall are mild in New London, with daytime highs in the 55° to 70 °F range and lows in the 40° to 50 °F range. The seaside location of the city creates a long growing season compared to areas inland. The first frost in the New London area is normally not until late October or early November, almost three weeks later than parts of northern Connecticut. Winters are cool with a mix of rainfall and snowfall, or mixed precipitation. New London normally sees fewer than 25 days annually with snow cover. In mid-winter, there can be large differences in low temperatures between areas along the coastline and areas well inland, sometimes as much as 15 °F.

Tropical cyclones (hurricanes/tropical storms) have struck Connecticut and the New London metropolitan area, although infrequently. Hurricane landfalls have occurred along the Connecticut coast in 1903, 1938, 1944, 1954 (Carol), 1960 (Donna), 1985 (Gloria). Tropical Storm Irene (2011) also caused moderate damage along the Connecticut coast, as did Hurricane Sandy (which made landfall in New Jersey) in 2012.

The Connecticut shoreline (including New London) lies within the broad transition zone where so-called "subtropical indicator" plants and other broadleaf evergreens can successfully be cultivated. New London averages about 90 days annually with freeze, about the same as Baltimore, Maryland[citation needed]. As such, many varieties of Southern Magnolia, Needle Palms, Loblolly and Longleaf Pines, Crape Myrtles, Aucuba japonica, Camellia, trunking Yucca, hardy bananas, Monkey Puzzle, copious types of evergreen Hollies, many East Asian (non-holly) broadleaf evergreen trees and shrubs, and certain varieties of figs may be grown in private and public gardens. The growing season is quite long in New London. Like much of coastal Connecticut and Long Island, NY, it averages close to 200 frost free days. The new 2023 USDA Garden Zone Map has New London in zone 7a. New London falls into the same garden zone as locations like Trenton, New Jersey, Wilmington, Delaware, or Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. By the mid-to-late 21st century, the area is expected to fall within USDA zone 8 according to some models.[26][27][28]

| Climate data for New London (Groton) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1957–2021 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

67 (19) |

78 (26) |

88 (31) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

93 (34) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

69 (21) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.6 (13.7) |

55.8 (13.2) |

65.5 (18.6) |

73.6 (23.1) |

81.9 (27.7) |

88.0 (31.1) |

91.6 (33.1) |

88.7 (31.5) |

84.7 (29.3) |

76.5 (24.7) |

67.4 (19.7) |

60.0 (15.6) |

92.6 (33.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.8 (3.8) |

40.8 (4.9) |

47.3 (8.5) |

56.9 (13.8) |

66.4 (19.1) |

75.2 (24.0) |

80.8 (27.1) |

79.8 (26.6) |

73.6 (23.1) |

63.3 (17.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

44.1 (6.7) |

60.0 (15.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.3 (−0.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

39.5 (4.2) |

48.9 (9.4) |

58.1 (14.5) |

67.3 (19.6) |

73.4 (23.0) |

72.5 (22.5) |

65.8 (18.8) |

55.2 (12.9) |

45.5 (7.5) |

36.8 (2.7) |

52.3 (11.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.8 (−4.6) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

40.9 (4.9) |

49.9 (9.9) |

59.3 (15.2) |

65.9 (18.8) |

65.1 (18.4) |

58.0 (14.4) |

47.1 (8.4) |

37.9 (3.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

44.5 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 4.1 (−15.5) |

6.9 (−13.9) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

38.1 (3.4) |

46.8 (8.2) |

56.0 (13.3) |

54.2 (12.3) |

43.6 (6.4) |

32.2 (0.1) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

14.2 (−9.9) |

1.5 (−16.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−12 (−24) |

0 (−18) |

14 (−10) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

47 (8) |

41 (5) |

29 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−10 (−23) |

−14 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.91 (99) |

3.42 (87) |

4.92 (125) |

4.40 (112) |

3.67 (93) |

3.93 (100) |

3.42 (87) |

4.19 (106) |

4.29 (109) |

4.42 (112) |

3.75 (95) |

4.59 (117) |

48.91 (1,242) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.8 (15) |

8.3 (21) |

3.9 (9.9) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

5.2 (13) |

24.5 (62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.4 | 9.7 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 12.4 | 127.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.1 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 9.9 |

| Source: NOAA[29][30] | |||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 5,150 | — | |

| 1810 | 3,238 | −37.1% | |

| 1820 | 3,330 | 2.8% | |

| 1830 | 4,335 | 30.2% | |

| 1840 | 5,519 | 27.3% | |

| 1850 | 8,991 | 62.9% | |

| 1860 | 10,115 | 12.5% | |

| 1870 | 9,576 | −5.3% | |

| 1880 | 10,537 | 10.0% | |

| 1890 | 13,757 | 30.6% | |

| 1900 | 17,548 | 27.6% | |

| 1910 | 19,659 | 12.0% | |

| 1920 | 25,688 | 30.7% | |

| 1930 | 29,640 | 15.4% | |

| 1940 | 30,456 | 2.8% | |

| 1950 | 30,551 | 0.3% | |

| 1960 | 34,182 | 11.9% | |

| 1970 | 31,630 | −7.5% | |

| 1980 | 28,842 | −8.8% | |

| 1990 | 28,540 | −1.0% | |

| 2000 | 25,671 | −10.1% | |

| 2010 | 27,620 | 7.6% | |

| 2020 | 27,367 | −0.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

Demographics

Recent estimates on demographics and economic status

According to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey, non-Hispanic whites made up 54.6% of New London's population. Non-Hispanic blacks made up 14.0% of the population. Asians of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.6% of the city's population. Multiracial individuals of non-Hispanic origin made up 4.3% of the population; people of mixed black and white ancestry made up 1.7% of the population. In addition, people of mixed black and Native American ancestry made up 1.0% of the population. People of mixed white and Native American ancestry made up 0.7% of the population; those of mixed white and Asian ancestry made up 0.4% of the populace. Hispanics and Latinos made up 21.9% of the population, of which 13.8% were Puerto Rican.[31]

The top five largest European ancestral ethnicities were Italian (10.5%), Irish (9.7%), German (7.4%), English (6.8%), and Polish (5.0%)

According to the survey, 74.4% of people over the age of 5 spoke only English at home. Approximately 16.0% of the population spoke Spanish at home.[32]

2020 census

As of the census[33][34] of 2020, there were 27,374 people and 11,125 households. The population density was 4,868.7 per square mile (1,879.8/km2). There were 12,119 housing units at an average density of 2,156.4 per square mile (832.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 56.2% White, 29.4% Hispanic or Latino of any race, 17.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.3% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 16.7% from other races, and 10.8% from two or more races.

There were 11,125 households, out of which 23.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.4% were married couples living together, 34.1% had a female householder with no partner present, and 27.8% had a male householder with no partner present. 14.7% of households had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.12 and the average family size was 2.84.[35]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 16.5% under the age of 18, 19.4% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 22.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males.[36]

The median income for a household in the city was $56,237, and the median income for a family was $65,357.[37] About 21.5% of the population was below the poverty line, including 36.4% of those under age 18 and 11.1% of those age 65 or over.[38]

Economy

New London was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades beginning in the early 19th century, along with Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts. The wealth that whaling brought into the city furnished the capital to fund much of the city's present architecture. The city subsequently became home to other shipping and manufacturing industries, but had gradually lost most of its industrial heart. The State Pier (south of the Gold Star Memorial Bridge) is being converted to support some of the offshore wind power in the United States.[39][40]

Arts and culture

Eugene O'Neill

Nobel laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Eugene O'Neill (1888–1953) lived in New London and wrote several plays in the city. An O'Neill archive is located at Connecticut College, and the family home, Monte Cristo Cottage,[41] is a museum and national historic landmark operated by the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center.

Music

Notable artists and ensembles include:

- Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1946 and led by Toshiyuki Shimada, who is also conductor of the Yale Symphony Orchestra in New Haven.

- The Idlers of the United States Coast Guard Academy, an all-male vocal group specializing in sea shanties and patriotic music.

- United States Coast Guard Band, founded in 1925 with the assistance of John Philip Sousa. Stationed at the United States Coast Guard Academy and attracting talented musicians from all parts of the country, the band is the official musical representative of the nation's oldest continuous seagoing service.

- The Can Kickers, a folk punk band.

Literature

In her Scenes in My Native Land, 1845, Lydia Sigourney includes the poem Sunrise at New London with descriptive passages relating to the district. [42]

Sites of interest

- Lyman Allyn Art Museum

- Ocean Beach Park[43]

- New London County Historical Society, Shaw-Perkins Mansion (1758)[44]

- New London Maritime Society, U.S. Custom House (1833),[45] landing site of Amistad (1839)