Henry A. Wise: Difference between revisions

→Return to Virginia and slavery: narration fix; added information; content on farm; added reference |

Copying from Category:Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia to Category:19th-century American legislators using Cat-a-lot |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 22 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American politician (1806–1876)}} |

{{Short description|American politician (1806–1876)}} |

||

{{distinguish|Henry Augustus Wise|Henry A. Wise (New York state senator)}} |

{{distinguish|Henry Augustus Wise|Henry A. Wise (New York state senator)}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

|image = Henry Alexander Wise, c1857.jpg |

| image = Henry Alexander Wise, c1857.jpg |

||

|order = 33rd |

| order = 33rd |

||

|office = Governor of Virginia |

| office = Governor of Virginia |

||

|term_start = January 1, 1856 |

| term_start = January 1, 1856 |

||

|term_end = January 1, 1860 |

| term_end = January 1, 1860 |

||

|lieutenant = [[Elisha W. McComas]]<br />[[William Lowther Jackson]] |

| lieutenant = [[Elisha W. McComas]]<br />[[William Lowther Jackson]] |

||

|predecessor = [[Joseph Johnson (Virginia politician)|Joseph Johnson]] |

| predecessor = [[Joseph Johnson (Virginia politician)|Joseph Johnson]] |

||

|successor = [[John Letcher]] |

| successor = [[John Letcher]] |

||

|office1 = 6th [[United States Ambassador to Brazil|United States Minister to Brazil]] |

| office1 = 6th [[United States Ambassador to Brazil|United States Minister to Brazil]] |

||

|term1 = August 10, 1844 – August 28, 1847 |

| term1 = August 10, 1844 – August 28, 1847 |

||

|president1 = [[John Tyler]] <br />[[James K. Polk]] |

| president1 = [[John Tyler]] <br />[[James K. Polk]] |

||

|predecessor1 = [[George H. Proffit]] |

| predecessor1 = [[George H. Proffit]] |

||

|successor1 = [[David Tod]] |

| successor1 = [[David Tod]] |

||

|office2 = Member of the<br>[[U.S. House of Representatives]]<br>from [[Virginia]] |

| office2 = Member of the<br>[[U.S. House of Representatives]]<br>from [[Virginia]] |

||

|constituency2 = {{ushr|VA|8|C}} (1833–1843)<br>{{ushr|VA|7|C}} (1843–1844) |

| constituency2 = {{ushr|VA|8|C}} (1833–1843)<br>{{ushr|VA|7|C}} (1843–1844) |

||

|term_start2 = March 4, 1833 |

| term_start2 = March 4, 1833 |

||

|term_end2 = February 12, 1844 |

| term_end2 = February 12, 1844 |

||

|predecessor2 = [[Richard Coke Jr.]] |

| predecessor2 = [[Richard Coke Jr.]] |

||

|successor2 = [[Thomas H. Bayly]] |

| successor2 = [[Thomas H. Bayly]] |

||

|birth_name = Henry Alexander Wise |

| birth_name = Henry Alexander Wise |

||

|birth_date = {{birth date|1806|12|3|mf=y}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1806|12|3|mf=y}} |

||

|birth_place = [[Accomac, Virginia|Drummondtown, Virginia]] |

| birth_place = [[Accomac, Virginia|Drummondtown, Virginia]] |

||

|death_date = {{death date and age|1876|09|12|1806|12|03}} |

| death_date = {{death date and age|1876|09|12|1806|12|03}} |

||

|death_place = [[Richmond, Virginia]] |

| death_place = [[Richmond, Virginia]] |

||

|party = [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian]] (1832–1834)<br>[[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]] (1834–1842)<br>[[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] (1842–1868)<br>[[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] (after 1868) |

| party = [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian]] (1832–1834)<br>[[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]] (1834–1842)<br>[[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] (1842–1868)<br>[[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] (after 1868) |

||

|alma_mater = [[Washington & Jefferson College|Washington College]]<br>[[Winchester Law School]] |

| alma_mater = [[Washington & Jefferson College|Washington College]]<br>[[Winchester Law School]] |

||

|profession = Politician, |

| profession = Politician, lawyer |

||

|religion = |

| religion = |

||

|signature = Henry A Wise Signature.svg |

| signature = Henry A Wise Signature.svg |

||

|battles = [[American Civil War]] |

| battles = [[American Civil War]] |

||

* [[Battle of Roanoke Island]] |

* [[Battle of Roanoke Island]] |

||

* [[Peninsula Campaign]] |

* [[Peninsula Campaign]] |

||

* [[Siege of Petersburg]] |

* [[Siege of Petersburg]] |

||

* [[Appomattox Campaign]] |

* [[Appomattox Campaign]] |

||

|allegiance = |

| allegiance = [[Confederate States]] |

||

| branch = [[Confederate States Army]] |

|||

|branch = {{army|CSA}} |

|||

|unit = [[Army of Northern Virginia]] |

| unit = [[Army of Northern Virginia]] |

||

|rank = [[Brigadier General]] |

| rank = [[Brigadier General]] |

||

|serviceyears = 1861–1865 |

| serviceyears = 1861–1865 |

||

| father = [[John Wise (Virginia politician)|John Wise]] |

|||

|children =14, including [[Richard Alsop Wise|Richard Alsop]] and [[John Sergeant Wise|John Sergeant]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Henry Alexander Wise''' (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, and |

'''Henry Alexander Wise''' (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, politician and slave owner<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Weil |first1=Julie Zauzmer |last2=Blanco |first2=Adrian |last3=Dominguez |first3=Leo |title=More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation. |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/interactive/2022/congress-slaveowners-names-list/ |access-date=February 20, 2023 |newspaper=Washington Post |language=en}}</ref> from [[Virginia]]. As the 33rd [[Governor of Virginia]], Wise served as a significant figure on the path to the [[American Civil War]], becoming heavily involved in [[Virginia v. John Brown|the 1859 trial of abolitionist John Brown]]. After leaving office in 1860, Wise also led the move toward Virginia's secession from the Union in reaction to the election of [[Abraham Lincoln]] and the [[Battle of Fort Sumter]]. |

||

In addition to serving as |

In addition to serving as governor, Wise represented Virginia in the [[United States House of Representatives]] from 1833 to 1844 and was the [[United States Ambassador to Brazil|United States Minister to Brazil]] during the presidencies of [[John Tyler]] and [[James K. Polk]]. During the [[American Civil War]], he was a [[General officer|general]] in the [[Confederate States Army]]. In politics, Wise was consecutively a [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian Democrat]], a [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig supporter]] of the National Bank, a dissident Whig supportive of President Tyler, a Democratic [[Secession in the United States|secessionist]], and a Republican supporter of President [[Ulysses S. Grant]] during [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]]. His sons [[Richard Alsop Wise]] and [[John Sergeant Wise]] both also served in the Confederate Army and the post-war United States House as Republicans. After the Civil War ended, Wise accepted that slavery had been abolished and advocated a peaceful national reunification. |

||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Wise was born in [[Accomac, Virginia|Drummondtown]] in [[Accomack County, Virginia]], to Major John Wise and his second wife Sarah Corbin Cropper; their families had long been settled there. |

Wise was born in [[Accomac, Virginia|Drummondtown]] in [[Accomack County, Virginia]], to Major [[John Wise (Virginia politician)|John Wise]] and his second wife Sarah Corbin Cropper; their families had long been settled there. Wise was of [[English-American|English]] and [[Scottish-American|Scottish]] descent.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/biographicalsket00hamb|title=A Biographical Sketch of Henry A. Wise : with a History of the Political Campaign in Virginia in 1855: to which is added a review of the position of parties in the Union, and a statement of the political issues: distinguishing them on the eve of the presidential campaign of 1856|first=James Pinkney|last=Hambleton|date=February 1, 2018|publisher=Richmond, Va., J. W. Randolph|access-date=February 1, 2018|via=Internet Archive}}</ref> He was privately tutored until his twelfth year, when he entered Margaret Academy, near Pungoteague in Accomack County. He graduated from Washington College (now [[Washington & Jefferson College]]) in 1825.<ref>{{cite web|title=Washington College 1806–1865 |work=U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives |publisher=Washington & Jefferson College |url=http://washjeff.cdmhost.com/cdm4/wash.php |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090716210909/http://washjeff.cdmhost.com/cdm4/wash.php |archive-date=July 16, 2009 |access-date=February 22, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> He was a member of the [[Literary societies at Washington & Jefferson College#Union Literary Society|Union Literary Society]] at [[Washington & Jefferson College|Washington College]].<ref>{{Cite book| last = McClelland| first = W.C.| chapter = A History of Literary Societies at Washington & Jefferson College| chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=t1QyAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA111| publisher = George H. Buchanan and Company| title = The Centennial Celebration of the Chartering of Jefferson College in 1802| year = 1903| location = Philadelphia| pages = 111–132| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=t1QyAAAAYAAJ| access-date = March 6, 2016| archive-date = August 13, 2020| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200813042618/https://books.google.com/books?id=t1QyAAAAYAAJ| url-status = live}}</ref> |

||

After attending [[Henry St. George Tucker, Sr.|Henry St. George Tucker's]] [[Winchester Law School]], Wise was [[bar association|admitted to the bar]] in 1828.<ref name="Savits">[https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2010/06/30/blame-it-on-rio/ Renee M. Savits, "Blame It On Rio"], ''UncommonWealth: Voices from the Library of Virginia,'' Library of Virginia, accessed |

After attending [[Henry St. George Tucker, Sr.|Henry St. George Tucker's]] [[Winchester Law School]], Wise was [[bar association|admitted to the bar]] in 1828.<ref name="Savits">[https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2010/06/30/blame-it-on-rio/ Renee M. Savits, "Blame It On Rio"], ''UncommonWealth: Voices from the Library of Virginia,'' Library of Virginia, accessed December 2, 2020</ref> He settled in [[Nashville, Tennessee]], in the same year to start a practice, but returned to Accomack County in 1830. |

||

==Marriage and family== |

==Marriage and family== |

||

Wise was considered a dependable family man.{{sfn|Richards|2007|p=35}} He was married three times. He was first married in 1828 to Anne Jennings, the daughter of Rev. Obadiah Jennings and Ann Wilson of [[Washington, Pennsylvania]].<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=ExYaAAAAIAAJ Jennings Cropper Wise, ''Col. John Wise of England and Virginia (1617–1695): His Ancestors and Descendants'', Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1918; Digitized 2007 by University of California, p. 196] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140111083504/http://books.google.com/books?id=ExYaAAAAIAAJ |date= |

Wise was considered a dependable family man.{{sfn|Richards|2007|p=35}} He was married three times. He was first married in 1828 to Anne Jennings, the daughter of Rev. Obadiah Jennings and Ann Wilson of [[Washington, Pennsylvania]].<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=ExYaAAAAIAAJ Jennings Cropper Wise, ''Col. John Wise of England and Virginia (1617–1695): His Ancestors and Descendants'', Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1918; Digitized 2007 by University of California, p. 196] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140111083504/http://books.google.com/books?id=ExYaAAAAIAAJ |date=January 11, 2014 }}, accessed March 20, 2008</ref> In 1837, Anne and one of their children died in a fire, leaving Henry with four children: two sons and two daughters. |

||

Wise married a second time in November 1840 |

Wise married a second time in November 1840 to Sarah Sergeant, the daughter of U.S. Representative [[John Sergeant (politician)|John Sergeant]] ([[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]]-[[Pennsylvania]]) and Margaretta Watmough of [[Philadelphia]]. Sarah gave birth to at least five children. She died of complications, along with her last child, soon after its birth on October 14, 1850.<ref>[http://www.ancestry.com 1850 US Census, St. George's Parish, Accomack Co, VA] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/19961028055925/http://www.ancestry.com/ |date=October 28, 1996 }}, accessed March 5, 2008; [http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/wise/wise.html John S. Wise, ''The End of an Era'', New York: Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1899, p. 39; Documents of the South Collection, University of North Carolina Website] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070808232029/http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/wise/wise.html |date=August 8, 2007 }}, accessed February 11, 2008</ref> Sarah's sister Margaretta married [[George G. Meade]], who was a major general for the Union in the [[American Civil War]]. |

||

In the nineteen years of marriage to his first two wives, Wise fathered fourteen children; seven survived to adulthood.<ref>Simpson, p. 23</ref> |

In the nineteen years of marriage to his first two wives, Wise fathered fourteen children; seven survived to adulthood.<ref>Simpson, p. 23</ref> |

||

Henry married a third time |

Henry married a third time to Mary Elizabeth Lyons in 1853.<ref>Simpson, p. 95.</ref> After serving as governor, Wise settled with Mary and his younger children in 1860 at Rolleston, an {{convert|884|acre|km2|adj=on}} plantation which he bought from his brother John Cropper Wise, who also continued to live there.<ref>Simpson, p. 222.</ref> It was located on the [[Eastern Branch Elizabeth River]] near [[Norfolk, Virginia]]. The property was first owned and developed by William and Susannah Moseley, English immigrants who settled there in 1649. Their descendants owned the property into the 19th century.<ref>[http://www.rolleston.org.uk/hall/virginia.htm Idris Bowen, "Rolleston Hall, Virginia"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080316042410/http://www.rolleston.org.uk/hall/virginia.htm |date=March 16, 2008 }}, ''The Rollestonian'', Spring 2002, accessed February 2, 2008</ref> |

||

After Wise entered Confederate service, he and his family abandoned Rolleston in 1862 as |

After Wise entered Confederate service, he and his family abandoned Rolleston in 1862 as U.S. Army soldiers took over Norfolk. Wise arranged for his family to reside in [[Rocky Mount, Virginia|Rocky Mount]], [[Franklin County, Virginia]]. After the Civil War, Henry and Mary Wise lived in [[Richmond, Virginia|Richmond]], where he resumed his legal career. |

||

==Political career== |

==Political career== |

||

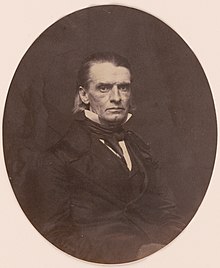

[[File:Henry A. Wise, Representative from Virginia.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Henry A. Wise (''1846'')]] |

[[File:Henry A. Wise, Representative from Virginia.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Henry A. Wise (''1846'')]] |

||

===U.S. Representative=== |

===U.S. Representative=== |

||

Henry A. Wise served as a U.S. Representative from 1833 to 1844. |

Henry A. Wise served as a U.S. Representative from 1833 to 1844. He was elected Representative in 1832 as a [[Jacksonian democracy|Jackson Democrat]]. To settle this election, Wise successfully fought a [[duel]] with his opponent.<ref name=nie>{{Cite NIE|wstitle=Wise, Henry Alexander|short=x}}</ref> Wise was re-elected in 1834, but then broke with the Jackson administration over the rechartering of the [[Second Bank of the United States|Bank of the United States]]. He became a [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]] but was sustained by his constituents. Wise was re-elected as a Whig in 1836, 1838, and 1840. |

||

While in Congress, Wise was the "faithful" opponent of [[John Quincy Adams]] |

While in Congress, Wise was the "faithful" opponent of [[John Quincy Adams]] in the latter's attempt to end the [[gag rule (United States)|gag rule]] and force Congress to respond to the many petitions asking it to end [[slavery in the District of Columbia]]. Adams described Wise in his diary as "loud, vociferous, declamatory, furibund, he raved about the hell-hound of abolition".<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Tunnell|first1=Ted|last2=Furgurson|first2=Ernest B.|date=1998|title=Ashes of Glory: Richmond at War.|journal=The Journal of Southern History|volume=64|issue=1|pages=17|doi=10.2307/2588092|issn=0022-4642|jstor=2588092}}</ref> |

||

On February 24, 1838, Wise served as the second to [[William J. Graves]] of [[Kentucky]] during the latter's duel with [[Jonathan Cilley]] of [[Maine]] at the [[Bladensburg Dueling Grounds]], in which Cilley was mortally wounded.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/A-fatal-duel-between-Members-in-1838/|title=A Fatal Duel Between Members in 1838 – US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives|website=history.house.gov|access-date= |

On February 24, 1838, Wise served as the second to [[William J. Graves]] of [[Kentucky]] during the latter's duel with [[Jonathan Cilley]] of [[Maine]] at the [[Bladensburg Dueling Grounds]], in which Cilley was mortally wounded.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/A-fatal-duel-between-Members-in-1838/|title=A Fatal Duel Between Members in 1838 – US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives|website=history.house.gov|access-date=February 1, 2018|archive-date=February 2, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180202012804/http://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/A-fatal-duel-between-Members-in-1838/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/pair-dueling-rifles-reveal-their-story|title=A pair of dueling rifles reveal their story|website=National Museum of American History|date=March 10, 2016 |access-date=February 1, 2018|archive-date=February 2, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180202012925/http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/pair-dueling-rifles-reveal-their-story|url-status=live}}</ref> He later wrote an account of the event that was published by his son John in the ''[[Saturday Evening Post]]'' in 1906.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://cilley.net/thecilleypages/cilley-en-o/e60.htm|title=Cilley – Exhibit|website=cilley.net|access-date=February 1, 2018|archive-date=May 7, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160507161444/http://cilley.net/thecilleypages/cilley-en-o/e60.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

[[File:John Tyler I.png|thumb|right|200px|'''President John Tyler''' (''1841'')<br> In 1844, Tyler appointed Wise U.S. Minister to Brazil.]] |

[[File:John Tyler I.png|thumb|right|200px|'''President John Tyler''' (''1841'')<br> In 1844, Tyler appointed Wise U.S. Minister to Brazil.]] |

||

In 1840 Wise was active in securing the nomination and election of [[John Tyler]] as [[Vice President of the United States|Vice President]] on the Whig ticket. Tyler succeeded to the presidency and then broke with the Whigs. Wise was one of a small group of Congress members, known derisively as the "Corporal's Guard," who supported Tyler during his struggles with the Whigs and was re-elected as a Tyler Democrat in 1842. Tyler nominated Wise three times as [[United States Ambassador to France|U.S. Minister]] to [[France]], but the Senate did not confirm the nomination.<ref name=Times/><ref>{{cite web |url=https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:1:./temp/~ammem_LGh7:: |title=Senate Executive Journal |access-date=February 7, 2017 |archive-date=February 8, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170208033704/https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw%3A1%3A.%2Ftemp%2F~ammem_LGh7%3A%3A |url-status=live }}</ref> |

In 1840 Wise was active in securing the nomination and election of [[John Tyler]] as [[Vice President of the United States|Vice President]] on the Whig ticket. Tyler succeeded to the presidency and then broke with the Whigs. Wise was one of a small group of Congress members, known derisively as the "Corporal's Guard," who supported Tyler during his struggles with the Whigs and was re-elected as a Tyler Democrat in 1842. Tyler nominated Wise three times as [[United States Ambassador to France|U.S. Minister]] to [[France]], but the Senate did not confirm the nomination.<ref name=Times/><ref>{{cite web |url=https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:1:./temp/~ammem_LGh7:: |title=Senate Executive Journal |access-date=February 7, 2017 |archive-date=February 8, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170208033704/https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw%3A1%3A.%2Ftemp%2F~ammem_LGh7%3A%3A |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

| Line 78: | Line 81: | ||

Wise returned to Virginia after leaving his minister post in Brazil. While in Brazil, Wise condemned the slave trade between the U.S. and Brazil. He thought it was the work of "hypocritical Yankees" and against American law. With such harsh criticism, he had given up his usefulness as a U.S. minister and was withdrawn. The Brazilian government practically kicked him out of office.{{sfn|Richards|2007|pp=35-37}} |

Wise returned to Virginia after leaving his minister post in Brazil. While in Brazil, Wise condemned the slave trade between the U.S. and Brazil. He thought it was the work of "hypocritical Yankees" and against American law. With such harsh criticism, he had given up his usefulness as a U.S. minister and was withdrawn. The Brazilian government practically kicked him out of office.{{sfn|Richards|2007|pp=35-37}} |

||

After Wise returned to Virginia he |

After Wise returned to Virginia, he planned to sell the people he enslaved. In 1849, Wise enslaved 19 people, one shy of planter status, and considered them his "children" and "responsibility". He knew that farming was not profitable in soil-depleted Virginia. Nevertheless, rather than emancipation, Wise intended to profit from selling the people he enslaved to California after gold had been discovered there in 1849. An enslaved person in Virginia was worth $1,000, but in California, an enslaved person would be worth $3,000 to $5,000 digging gold.{{sfn|Richards|2007|pp=35-37}} Wise's plan, however, was thwarted when California joined the United States as a free state in the [[Compromise of 1850]].<ref>[[#California Admission Day September 9, 1850|California Admission Day September 9, 1850]].</ref> |

||

Wise's |

Wise's plantation comprised 400 acres, and only about half were productive. Wise grew corn, oats, and [[sweet potatoes]]. Wise also raised livestock and maintained peach and pear orchards. His farm most likely profited $500 a year.{{sfn|Richards|2007|pp=35-37}} |

||

===Governor of Virginia=== |

===Governor of Virginia=== |

||

Wise returned to the United States in 1847 and resumed |

Wise returned to the United States in 1847 and resumed legal practice. He identified with the Jacksonian Democratic Party and was active in politics. A delegate to the [[Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850]], Wise opposed any reforms, insisting that the protection of slavery came first.<ref>Shade, William G., Democratizing the Old Dominion: Virginia and the Second Party System, 1824–1861. 1996 {{ISBN|978-0-8139-1654-5}}, pp. 276–277</ref> In the statewide election of 1855, Wise was elected [[Governor of Virginia]] as a Democrat, defeating [[Know-Nothing]] candidate [[Thomas S. Flournoy]]. He was the [[List of Governors of Virginia|33rd governor of Virginia]], serving from 1856 to 1860, and the last [[Eastern Shore of Virginia|Eastern Shore]] governor until [[Ralph Northam]] was elected [[Virginia gubernatorial election, 2017|in 2017]].<ref>Vaughn, Carol; [http://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/2017/11/07/eastern-shore-native-ralph-northam-virginia-governor/834510001/ 'Eastern Shore native Ralph Northam will be the next Virginia governor'] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180110174720/http://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/2017/11/07/eastern-shore-native-ralph-northam-virginia-governor/834510001/ |date=January 10, 2018 }}; ''Delmarva Now'', November 7, 2017</ref> [[Wise County, Virginia]], was named after him when it was established in 1856. |

||

Although he was visibly and unapologetically a defender of slavery, he opposed the imposition of the pro-slavery [[Lecompton Constitution]] on [[Kansas Territory]], as |

Although he was visibly and unapologetically a defender of slavery, he opposed the imposition of the pro-slavery [[Lecompton Constitution]] on [[Kansas Territory]], as residents of Kansas had not approved it: "And why impose this Constitution of a minority on a majority? ''[[Cui bono]]?'' ["Who would that benefit?"] Does any Southern man imagine that this is a practicable or sufferable way of making a slave State?"<ref>{{cite book |

||

|title=The life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia, 1806-1876 |

|title=The life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia, 1806-1876 |

||

|last=Wise |

|last=Wise |

||

| Line 92: | Line 95: | ||

|location=New York |

|location=New York |

||

|url=https://archive.org/details/lifehenryawisev01wisegoog/page/n260/mode/2up |

|url=https://archive.org/details/lifehenryawisev01wisegoog/page/n260/mode/2up |

||

|publisher=[[Macmillan Inc.|Macmillan]]}}</ref>{{rp|236}} This stance played a large role in scuttling his preparations for a bid to challenge incumbent [[Robert M.T. Hunter]] in the [[1858-59 United States Senate elections|Senate election in 1858]], as Hunter was a supporter of the Lecompton Constitution. |

|||

|publisher=[[Macmillan Inc.|Macmillan]]}}</ref>{{rp|236}} |

|||

Under the [[Virginia Constitution]], governors cannot serve successive terms, so he was not a candidate for reelection in 1860. |

Under the [[Virginia Constitution]], governors cannot serve successive terms, so he was not a candidate for reelection in 1860. |

||

| Line 122: | Line 125: | ||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428032334/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/59131494/interview-of-john-brown/ |

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428032334/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/59131494/interview-of-john-brown/ |

||

|url-status=live |

|url-status=live |

||

}}</ref> He |

}}</ref> He traveled from Richmond to Harpers Ferry immediately and interviewed him at length. After returning to Richmond, in a widely reported speech, he praised Brown,<ref>{{cite news |

||

|title=Gov. Wise's Return from Harper's Ferry{{snd}}His Speech in Richmond |

|title=Gov. Wise's Return from Harper's Ferry{{snd}}His Speech in Richmond |

||

|newspaper=[[New York Daily Herald]] |

|newspaper=[[New York Daily Herald]] |

||

| Line 161: | Line 164: | ||

|date=July 1921 |

|date=July 1921 |

||

|journal=[[Ohio History Journal]] |

|journal=[[Ohio History Journal]] |

||

|access-date=2021 |

|access-date=June 1, 2021 |

||

|archive-date=2021 |

|archive-date=June 2, 2021 |

||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602220258/https://resources.ohiohistory.org/ohj/search/display.php?page=50&ipp=20&searchterm=shakers&vol=30&pages=184-289 |

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602220258/https://resources.ohiohistory.org/ohj/search/display.php?page=50&ipp=20&searchterm=shakers&vol=30&pages=184-289 |

||

|url-status=live |

|url-status=live |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

However, |

However, Governor Wise did many things to augment rather than reduce tensions: by insisting he was tried in Virginia and turning Charles Town into an armed camp full of state militia units. "At every juncture he chose to escalate rather than pacify sectional animosity."<ref name=Nudelman>{{cite book |

||

|title=John Brown's body: slavery, violence & the culture of war |

|title=John Brown's body: slavery, violence & the culture of war |

||

|first=Franny |

|first=Franny |

||

| Line 176: | Line 179: | ||

|page=27}}</ref> |

|page=27}}</ref> |

||

Some sources say that Wise signed John Brown's [[death warrant]],<ref name=nie/> |

Some sources say that Wise signed John Brown's [[death warrant]],<ref name=nie/> but this is incorrect; under Virginia law, the governor did not need to sign such a document, as Wise pointed out. After Brown was sentenced to death, Wise could have [[commutate]]d his sentence to life imprisonment,<ref>{{cite book |

||

|title=His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid |

|title=His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid |

||

|editor-first=Paul |

|editor-first=Paul |

||

| Line 188: | Line 191: | ||

|last=McGlone |

|last=McGlone |

||

|chapter=John Brown, Henry Wise, and the Politics of Insanity |

|chapter=John Brown, Henry Wise, and the Politics of Insanity |

||

|pages=213–252, at p. 225}}</ref> as was recommended to him by many people. The efforts to pressure Wise became so intense that according to the ''Richmond Enquirer'', he was offered the presidency in exchange for a pardon.<ref>{{cite news |

|pages=213–252, at p. 225}}</ref> as was recommended to him by many people. The efforts to pressure Wise became so intense that, according to the ''Richmond Enquirer'', he was offered the presidency in exchange for a pardon.<ref>{{cite news |

||

|title=Presidency for a pardon |

|title=Presidency for a pardon |

||

|newspaper=[[Richmond Enquirer]] ([[Richmond, Virginia]]) |

|newspaper=[[Richmond Enquirer]] ([[Richmond, Virginia]]) |

||

| Line 210: | Line 213: | ||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428033102/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/68811745/wise-pressured-to-pardon-john-brown/ |

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428033102/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/68811745/wise-pressured-to-pardon-john-brown/ |

||

|url-status=live |

|url-status=live |

||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|page=xiii |

|||

|first=Louis |

|||

|last=DeCaro Jr. |

|||

|authorlink=Louis DeCaro Jr. |

|||

|title= Freedom's Dawn. the Last Days of John Brown in Virginia |

|||

|location=[[Lanham, Maryland]] |

|||

|publisher=[[Rowman & Littlefield]] |

|||

|year=2015 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|title=Threats against Gov. Wise and Virginia |

|title=Threats against Gov. Wise and Virginia |

||

|newspaper=[[Gettysburg Compiler]] ([[Gettysburg, Pennsylvania]]) |

|newspaper=[[Gettysburg Compiler]] ([[Gettysburg, Pennsylvania]]) |

||

| Line 231: | Line 243: | ||

|publisher=[[Houghton, Mifflin]]}}</ref> |

|publisher=[[Houghton, Mifflin]]}}</ref> |

||

One option Wise considered was to find Brown insane, which would have avoided the death penalty and sent him to an [[Lunatic asylum#Institutionalisation|insane asylum]]. He had been given 19 affidavits from relatives and friends about the alleged madness of Brown and several of his relatives. This would have de-escalated the crisis, not turning Brown into abolition's martyr and hero, as he immediately became. However |

One option Wise considered was to find Brown insane, which would have avoided the death penalty and sent him to an [[Lunatic asylum#Institutionalisation|insane asylum]]. He had been given 19 affidavits from relatives and friends about the alleged madness of Brown and several of his relatives. This would have de-escalated the crisis, not turning Brown into abolition's martyr and hero, as he immediately became. However, after his interview with Brown in the engine house, Wise had said publicly that Brown was not insane at all. Before the trial, Brown had insisted that he did not want an insanity defense. |

||

The prevailing political sentiment in Virginia was against de-escalation and strongly in favor of executing Brown. Wise was emerging as a national figure |

The prevailing political sentiment in Virginia was against de-escalation and strongly in favor of executing Brown. Wise was emerging as a national figure and had presidential ambitions. To take any action that would have prevented Brown's execution would have damaged Wise politically more than it could have helped him. On the contrary, the popularity Wise gained in the South for executing Brown, and the other captured members of his party led to Southern support for him as a presidential candidate in 1860.<ref name=Times>{{cite news |

||

|title=He didn't spare John Brown's body: the tumultuous times of Virginia Gov. Henry Wise |

|title=He didn't spare John Brown's body: the tumultuous times of Virginia Gov. Henry Wise |

||

|first=Jeff E. |

|first=Jeff E. |

||

| Line 285: | Line 297: | ||

===Secession crisis=== |

===Secession crisis=== |

||

In 1857, during the incoming Presidency of [[James Buchanan]], Wise served as one of Buchanan's chief Southern advisors. Other Southern advisors to Buchanan included Senator [[John Slidell]] of Louisiana and Robert Tyler of Virginia. Tyler was the son of President [[John Tyler]]. Buchanan, although a [[Pennsylvania]] Democrat, held Southern sympathies, was a strict constructionist |

In 1857, during the incoming Presidency of [[James Buchanan]], Wise served as one of Buchanan's chief Southern advisors. Other Southern advisors to Buchanan included Senator [[John Slidell]] of Louisiana and Robert Tyler of Virginia. Tyler was the son of President [[John Tyler]]. Buchanan, although a [[Pennsylvania]] Democrat, held Southern sympathies, was a strict constructionist and detested abolitionists and "Black Republicans". {{sfn|Richards|2007|pp=195-196}} |

||

During the secession crisis of 1860–61, Wise was a |

During the secession crisis of 1860–61, Wise was a fervent advocate of immediate secession by Virginia. He was a member of the [[Virginia Secession Convention of 1861|Virginia secession convention of 1861]]. Frustrated with the convention's inaction through mid-April, Wise helped plan actions by Virginia state militia to seize the Federal Arsenal at [[Harpers Ferry]] and the [[Gosport Navy Yard]] in [[Norfolk]]. These actions were not authorized by the incumbent Governor [[John Letcher|Letcher]] or the militia's commanders. |

||

These plans were pre-empted by the [[Battle of Fort Sumter|bombardment of Fort Sumter]] on April 12–14 |

These plans were pre-empted by the [[Battle of Fort Sumter|bombardment of Fort Sumter]] on April 12–14 and Lincoln's call on April 15 for troops to suppress the rebellion. After a further day and a half of the debate, the convention voted for secession 85 representatives in favor and 55 against.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Lepore|first=Jill|title=These Truths: A History of the United States|publisher=W. W. Norton & Company|year=2018|isbn=978-0-393-63524-9|location=New York|pages=292|language=English}}</ref> On April 17, during the latter stage of the debate, Wise irrupted into the debate a gun in hand, declared Virginia was now at war with the United States, and that he would kill anyone who would try to shoot him for treason.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

===Electoral history=== |

===Electoral history=== |

||

| Line 299: | Line 311: | ||

==Civil War== |

==Civil War== |

||

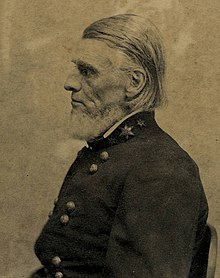

[[File:Portrait of Gen. Henry Alexander Wise (cropped).jpg|right|thumb|Gen. Wise during the American Civil War.]] |

[[File:Portrait of Gen. Henry Alexander Wise (cropped).jpg|right|thumb|Gen. Wise during the American Civil War.]] |

||

After Virginia declared secession, Wise joined the [[Confederate States Army]] (CSA). Because of his political prominence and secessionist reputation, he was commissioned as a [[Brigadier General (CSA)|brigadier general]], despite having no formal military training.<ref name=EV>McClure, J. M. [http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876 Henry A. Wise (1806–1876)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150423070649/http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876 |date= |

After Virginia declared secession, Wise joined the [[Confederate States Army]] (CSA). Because of his political prominence and secessionist reputation, he was commissioned as a [[Brigadier General (CSA)|brigadier general]], despite having no formal military training.<ref name=EV>McClure, J. M. [http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876 Henry A. Wise (1806–1876)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150423070649/http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876 |date=April 23, 2015 }}. (April 5, 2011). ''Encyclopedia Virginia''.</ref> He was assigned to the western Virginia region, where his political support would be helpful. Brigadier General [[John B. Floyd]], another former governor of Virginia, was also sent there. In the summer of 1861, Wise and Floyd feuded over who was the superior officer. At the height of the feud, General Floyd blamed Wise for the Confederate defeat at the [[Battle of Carnifex Ferry]], stating that Wise refused to come to his aid.<ref name=gazette>[http://civilwardailygazette.com/2011/09/25/confederate-general-henry-wise-relieved-of-duty-contraband-allowed-in-navy/ Civil War Daily Gazette Confederate General Henry Wise Relieved of Duty; “Contraband” Allowed in Navy.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131221002748/http://civilwardailygazette.com/2011/09/25/confederate-general-henry-wise-relieved-of-duty-contraband-allowed-in-navy/ |date=December 21, 2013 }} Retrieved November 21, 2012.</ref> The feud was not resolved until [[Virginia House of Delegates|Virginia Delegate]] [[Mason Mathews]], whose son [[Alexander F. Mathews]] was Wise's aide-de-camp, spent several days in the camps of both Wise and Floyd. Afterward, he wrote to [[President of the Confederate States of America|President]] [[Jefferson Davis]] urging that both men be removed.<ref name=Rice>[[Otis K. Rice|Rice, Otis K.]] (1986) ''A History of Greenbrier County''. Greenbrier Historical Society, p. 264</ref><ref name=Rebellion>Cowles, Calvin Duvall (1897). [http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moawar&cc=moawar&idno=waro0005&node=waro0005%3A3&view=image&seq=880&size=100 ''The War of the Rebellion: A compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160108005435/http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moawar&cc=moawar&idno=waro0005&node=waro0005%3A3&view=image&seq=880&size=100 |date=January 8, 2016 }}. Government Print Office: 1897.</ref> Davis subsequently removed Wise from his command in western Virginia.<ref name=gazette/> |

||

| ⚫ | In early 1862, Wise was assigned to command the District of [[Roanoke Island]], threatened by U.S. Navy forces. He fell ill with [[pleurisy]] and was not present for the [[Battle of Roanoke Island]] when U.S. Army soldiers stormed the island. He was blamed for the loss, but for his part, complained bitterly about inadequate forces to defend the island.{{Citation needed|date=June 2013}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In early 1862, Wise was assigned to command the District of [[Roanoke Island]], |

||

In 1864, Wise commanded a brigade in the Department of North Carolina & Southern Virginia. His brigade defended Petersburg and was credited with saving the city at the [[First Battle of Petersburg]] and to an extent at the [[Second Battle of Petersburg]]. From June 17 until November 1864, Wise commanded the Military District of the City of Petersburg. He resumed command of his brigade in November and led it during the final stages of the [[Siege of Petersburg]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

He was with [[Robert E. Lee]] at [[Battle of Appomattox Court House|Appomattox Court House]], where he fought bravely but urged Lee to surrender. With other Confederate officials, he was taken prisoner after the surrender. |

|||

==Postwar political statements== |

==Postwar political statements== |

||

| Line 323: | Line 337: | ||

}}</ref>|author=|title=|source=}} |

}}</ref>|author=|title=|source=}} |

||

The Confederate Constitution (''CC''), adopted on March 11, 1861, banned the international slave trade. However, the ''CC'' prohibited |

The Confederate Constitution (''CC''), adopted on March 11, 1861, banned the international slave trade. However, the ''CC'' prohibited passing laws that would make illegal "the right of property in negro slaves." According to historian Stephanie McCurry of Columbia University, the ''CC'' was a product of White men who held all the political power for themselves. Under the ''CC'', Black people and women were not entitled to political power.<ref>[[#Jay Reeves (March 10, 2021)|Jay Reeves (March 10, 2021)]]</ref> |

||

==Postbellum activities== |

==Postbellum activities== |

||

[[File:Robert E Lee with his Generals, 1869.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Wise (top row, second from right) with [[Robert E. Lee]] and Confederate officers, |

[[File:Robert E Lee with his Generals, 1869.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Wise (top row, second from right) with [[Robert E. Lee]] and Confederate officers, c. 1869.]] |

||

After the war, Wise resumed his law practice in Richmond |

After the war, Wise resumed his law practice in Richmond and settled there for the rest of his life. In 1865 he tried to reclaim Rolleston, his plantation outside [[Norfolk, Virginia|Norfolk]], but was turned down by General Grant, considering that he did not make the [[Ironclad Oath]].<ref>{{cite news |

||

|title=Henry A. Wise |

|title=Henry A. Wise |

||

|newspaper=[[The Cleveland Leader|Cleveland Daily Leader]] ([[Cleveland, Ohio]]) |

|newspaper=[[The Cleveland Leader|Cleveland Daily Leader]] ([[Cleveland, Ohio]]) |

||

| Line 338: | Line 352: | ||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428032643/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/62466747/grant-turns-down-henry-wises-request/ |

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428032643/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/62466747/grant-turns-down-henry-wises-request/ |

||

|url-status=live |

|url-status=live |

||

}}</ref> He was told that he had abandoned that residence when he moved his family to another plantation at [[Rocky Mount, Virginia]]. The U.S. commander in Norfolk, Maj. Gen. [[Alfred H. Terry]], appropriated it and other plantations for the [[Freedmen's Bureau]] |

}}</ref> He was told that he had abandoned that residence when he moved his family to another plantation at [[Rocky Mount, Virginia]]. The U.S. commander in Norfolk, Maj. Gen. [[Alfred H. Terry]], appropriated it and other plantations for the [[Freedmen's Bureau]] to establish schools for formerly enslaved people and their children. Two hundred freedmen were said to be taking classes at Rolleston.<ref>[https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9B0DE6D8123EEE34BC4950DFB166838E679FDE The Wise and Terry Letters, 31 Jul 1865, ''The New York Times''], accessed February 4, 2008; [http://www.rolleston.org.uk/hall/virginia.htm Idris Bowen, "Rolleston Hall, Virginia", ''The Rollestonian'', Spring 2002] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080316042410/http://www.rolleston.org.uk/hall/virginia.htm |date=March 16, 2008 }}, accessed February 2, 2008</ref> A picture of John Brown had been placed in the parlor. "The officers who confiscated the place found in the house among numerous other papers a plan of secession drawn up by Wise in 1857, and approved by Jeff Davis and several other prominent men In the South."<ref>{{cite news |

||

|title=(Untitled) |

|title=(Untitled) |

||

|newspaper=[[Pittsburgh Gazette]] ([[Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]]) |

|newspaper=[[Pittsburgh Gazette]] ([[Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]]) |

||

| Line 384: | Line 398: | ||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

Wise became a Republican and strong supporter of President [[Ulysses S. Grant]]. |

Wise became a Republican and strong supporter of President [[Ulysses S. Grant]]. Unlike many other politicians, he did not emphasize his Confederate service or ever seek a pardon.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876#start_entry|title=Wise, Henry A. (1806–1876)|website=www.encyclopediavirginia.org|access-date=February 1, 2018|archive-date=February 2, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180202072136/https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Wise_Henry_A_1806-1876#start_entry|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

While working in his law career, Wise wrote a book based on his public service, entitled [https://archive.org/details/sevendecades00wiserich/page/254/mode/2up ''Seven Decades of the Union''] (1872). |

|||

==Death and legacy== |

==Death and legacy== |

||

| Line 392: | Line 406: | ||

Wise died in 1876 and was buried at [[Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia)|Hollywood Cemetery]] in Richmond. |

Wise died in 1876 and was buried at [[Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia)|Hollywood Cemetery]] in Richmond. |

||

His son Capt. Obediah Jennings Wise<ref>{{ |

His son Capt. Obediah Jennings Wise<ref>{{citation |url=https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/2234|title=O. Jennings Wise Letters|last=Wise | first=Obadiah Jennings|date=January 1, 1944|access-date=February 1, 2018|journal=|archive-date=July 21, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190721210725/https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/2234|url-status=live}}</ref> died in 1862 under his father's command at Roanoke Island.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/mssc/roanoke/13death.htm|title=Death of O. Jennings Wise: Battle of Roanoke Island: Online Exhibit: New York State Library|website=www.nysl.nysed.gov|access-date=February 1, 2018|archive-date=February 17, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170217161825/http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/mssc/roanoke/13death.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Another son, [[Richard Alsop Wise|Richard]], after service in the Confederate Army, studied medicine and taught chemistry. He also became a Virginia legislator and US Representative. A third son, [[John Sergeant Wise|John]], served in the Confederate Army as a [[Virginia Military Institute|VMI cadet]]; he also later became an attorney and was elected as a US Representative. Both Richard Wise and John Wise were [[Republican Party (United States)|Republicans]] like their father. Another son, Henry A. Wise, Jr. (1834–1869), entered the ministry and assisted family friend Rev. Joshua Peterkin at [[St. James Episcopal Church (Richmond, Virginia)|St. James Episcopal Church]] in Richmond before resigning in 1859, a decade before his death.<ref>Minor T. Weisiger, Donald R. Traser, E. Randolph Trice and Margaret T. Peters, ''Not Hearers Only'' (Richmond, 1986), preface</ref> |

||

Henry A. Wise's grandson Barton Haxall Wise wrote a biography of the former governor, entitled ''The Life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia'' (New York, 1899).<ref name=Barton>{{cite book |

Henry A. Wise's grandson Barton Haxall Wise wrote a biography of the former governor, entitled ''The Life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia'' (New York, 1899).<ref name=Barton>{{cite book |

||

| Line 401: | Line 415: | ||

|location=New York |

|location=New York |

||

|publisher=[[Macmillan Inc.]] |

|publisher=[[Macmillan Inc.]] |

||

|url=https://archive.org/details/lifehenryawisev01wisegoog/page/n12/mode/2up}}</ref> Another grandson, the lawyer and soldier Jennings Cropper Wise (1881–1968, son of John Sergeant Wise), wrote ''The Early History of the Eastern Shore of Virginia'' and dedicated it to his grandfather. He |

|url=https://archive.org/details/lifehenryawisev01wisegoog/page/n12/mode/2up}}</ref> Another grandson, the lawyer and soldier Jennings Cropper Wise (1881–1968, son of John Sergeant Wise), wrote ''The Early History of the Eastern Shore of Virginia'' and dedicated it to his grandfather. He quoted Governor Wise: "I have met the Black Knight with his visor down, and his shield and lance are broken."<ref>Jennings Cropper Wise, ''Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke: or the Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century'' (Richmond: The Bell, Book and Stationary Co. 1911)</ref> |

||

Counties were named in his honor in Virginia ([[Wise County, Virginia]]) and Texas ([[Wise County, Texas]]). |

Counties were named in his honor in Virginia ([[Wise County, Virginia]]) and Texas ([[Wise County, Texas]]). |

||

==Archival material== |

==Archival material== |

||

The Wise family papers, 1836-1928 (350 items, available on microfilm), and the Henry A. Wise papers, 1850-1869 (90 items), are held by the [[Library of Congress]]. The numerous documents from his service as Governor are in the [[Library of Virginia]] |

The Wise family papers, 1836-1928 (350 items, available on microfilm), and the Henry A. Wise papers, 1850-1869 (90 items), are held by the [[Library of Congress]]. The numerous documents from his service as Governor are in the [[Library of Virginia]]. |

||

==Writing== |

==Writing== |

||

| Line 539: | Line 553: | ||

[[Category:19th-century American diplomats]] |

[[Category:19th-century American diplomats]] |

||

[[Category:Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia]] |

[[Category:Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives]] |

[[Category:Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives]] |

||

[[Category:Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia]] |

[[Category:Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia]] |

||

[[Category:Democratic Party governors of Virginia]] |

[[Category:Democratic Party governors of Virginia]] |

||

[[Category:19th-century |

[[Category:19th-century Virginia politicians]] |

||

[[Category:19th-century American lawyers]] |

[[Category:19th-century American lawyers]] |

||

[[Category:Virginia Republicans]] |

[[Category:Virginia Republicans]] |

||

[[Category:John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry]] |

[[Category:John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:American duellists]] |

[[Category:American duellists]] |

||

[[Category:Ambassadors of the United States to Brazil]] |

[[Category:Ambassadors of the United States to Brazil]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Politicians from Richmond, Virginia]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Politicians from Norfolk, Virginia]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Fire-Eaters]] |

||

[[Category:American male non-fiction writers]] |

[[Category:American male non-fiction writers]] |

||

[[Category:Historians from Virginia]] |

[[Category:Historians from Virginia]] |

||

[[Category:Wise family of Virginia]] |

[[Category:Wise family of Virginia]] |

||

[[Category:Winchester Law School alumni]] |

[[Category:Winchester Law School alumni]] |

||

[[Category:Members of the United States House of Representatives who owned slaves]] |

|||

[[Category:Duellists]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 14:46, 1 August 2024

Henry A. Wise | |

|---|---|

| |

| 33rd Governor of Virginia | |

| In office January 1, 1856 – January 1, 1860 | |

| Lieutenant | Elisha W. McComas William Lowther Jackson |

| Preceded by | Joseph Johnson |

| Succeeded by | John Letcher |

| 6th United States Minister to Brazil | |

| In office August 10, 1844 – August 28, 1847 | |

| President | John Tyler James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | George H. Proffit |

| Succeeded by | David Tod |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1833 – February 12, 1844 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Coke Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Thomas H. Bayly |

| Constituency | 8th district (1833–1843) 7th district (1843–1844) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henry Alexander Wise December 3, 1806 Drummondtown, Virginia |

| Died | September 12, 1876 (aged 69) Richmond, Virginia |

| Political party | Jacksonian (1832–1834) Whig (1834–1842) Democratic (1842–1868) Republican (after 1868) |

| Children | 14, including Richard Alsop and John Sergeant |

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | Washington College Winchester Law School |

| Profession | Politician, lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Unit | Army of Northern Virginia |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Henry Alexander Wise (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, politician and slave owner[1] from Virginia. As the 33rd Governor of Virginia, Wise served as a significant figure on the path to the American Civil War, becoming heavily involved in the 1859 trial of abolitionist John Brown. After leaving office in 1860, Wise also led the move toward Virginia's secession from the Union in reaction to the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Battle of Fort Sumter.

In addition to serving as governor, Wise represented Virginia in the United States House of Representatives from 1833 to 1844 and was the United States Minister to Brazil during the presidencies of John Tyler and James K. Polk. During the American Civil War, he was a general in the Confederate States Army. In politics, Wise was consecutively a Jacksonian Democrat, a Whig supporter of the National Bank, a dissident Whig supportive of President Tyler, a Democratic secessionist, and a Republican supporter of President Ulysses S. Grant during Reconstruction. His sons Richard Alsop Wise and John Sergeant Wise both also served in the Confederate Army and the post-war United States House as Republicans. After the Civil War ended, Wise accepted that slavery had been abolished and advocated a peaceful national reunification.

Early life

[edit]Wise was born in Drummondtown in Accomack County, Virginia, to Major John Wise and his second wife Sarah Corbin Cropper; their families had long been settled there. Wise was of English and Scottish descent.[2] He was privately tutored until his twelfth year, when he entered Margaret Academy, near Pungoteague in Accomack County. He graduated from Washington College (now Washington & Jefferson College) in 1825.[3] He was a member of the Union Literary Society at Washington College.[4]

After attending Henry St. George Tucker's Winchester Law School, Wise was admitted to the bar in 1828.[5] He settled in Nashville, Tennessee, in the same year to start a practice, but returned to Accomack County in 1830.

Marriage and family

[edit]Wise was considered a dependable family man.[6] He was married three times. He was first married in 1828 to Anne Jennings, the daughter of Rev. Obadiah Jennings and Ann Wilson of Washington, Pennsylvania.[7] In 1837, Anne and one of their children died in a fire, leaving Henry with four children: two sons and two daughters.

Wise married a second time in November 1840 to Sarah Sergeant, the daughter of U.S. Representative John Sergeant (Whig-Pennsylvania) and Margaretta Watmough of Philadelphia. Sarah gave birth to at least five children. She died of complications, along with her last child, soon after its birth on October 14, 1850.[8] Sarah's sister Margaretta married George G. Meade, who was a major general for the Union in the American Civil War.

In the nineteen years of marriage to his first two wives, Wise fathered fourteen children; seven survived to adulthood.[9]

Henry married a third time to Mary Elizabeth Lyons in 1853.[10] After serving as governor, Wise settled with Mary and his younger children in 1860 at Rolleston, an 884-acre (3.58 km2) plantation which he bought from his brother John Cropper Wise, who also continued to live there.[11] It was located on the Eastern Branch Elizabeth River near Norfolk, Virginia. The property was first owned and developed by William and Susannah Moseley, English immigrants who settled there in 1649. Their descendants owned the property into the 19th century.[12]

After Wise entered Confederate service, he and his family abandoned Rolleston in 1862 as U.S. Army soldiers took over Norfolk. Wise arranged for his family to reside in Rocky Mount, Franklin County, Virginia. After the Civil War, Henry and Mary Wise lived in Richmond, where he resumed his legal career.

Political career

[edit]

U.S. Representative

[edit]Henry A. Wise served as a U.S. Representative from 1833 to 1844. He was elected Representative in 1832 as a Jackson Democrat. To settle this election, Wise successfully fought a duel with his opponent.[13] Wise was re-elected in 1834, but then broke with the Jackson administration over the rechartering of the Bank of the United States. He became a Whig but was sustained by his constituents. Wise was re-elected as a Whig in 1836, 1838, and 1840.

While in Congress, Wise was the "faithful" opponent of John Quincy Adams in the latter's attempt to end the gag rule and force Congress to respond to the many petitions asking it to end slavery in the District of Columbia. Adams described Wise in his diary as "loud, vociferous, declamatory, furibund, he raved about the hell-hound of abolition".[14]

On February 24, 1838, Wise served as the second to William J. Graves of Kentucky during the latter's duel with Jonathan Cilley of Maine at the Bladensburg Dueling Grounds, in which Cilley was mortally wounded.[15][16] He later wrote an account of the event that was published by his son John in the Saturday Evening Post in 1906.[17]

In 1844, Tyler appointed Wise U.S. Minister to Brazil.

In 1840 Wise was active in securing the nomination and election of John Tyler as Vice President on the Whig ticket. Tyler succeeded to the presidency and then broke with the Whigs. Wise was one of a small group of Congress members, known derisively as the "Corporal's Guard," who supported Tyler during his struggles with the Whigs and was re-elected as a Tyler Democrat in 1842. Tyler nominated Wise three times as U.S. Minister to France, but the Senate did not confirm the nomination.[18][19]

U.S. Minister to Brazil

[edit]In 1844, Tyler appointed Wise as U.S. Minister (ambassador) to Brazil. Wise resigned as Representative to take up this office. He served from 1844 to 1847.[5] Two of his children were born in Rio de Janeiro. In Brazil, Wise worked on issues related to trade and tariffs, Brazilian concerns about the US annexation of Texas, and establishing diplomatic relations with Paraguay.[5] (Wise supported the annexation of Texas by the United States. Wise County, Texas, was named in his honor.)

Return to Virginia and slavery

[edit]Wise returned to Virginia after leaving his minister post in Brazil. While in Brazil, Wise condemned the slave trade between the U.S. and Brazil. He thought it was the work of "hypocritical Yankees" and against American law. With such harsh criticism, he had given up his usefulness as a U.S. minister and was withdrawn. The Brazilian government practically kicked him out of office.[20]

After Wise returned to Virginia, he planned to sell the people he enslaved. In 1849, Wise enslaved 19 people, one shy of planter status, and considered them his "children" and "responsibility". He knew that farming was not profitable in soil-depleted Virginia. Nevertheless, rather than emancipation, Wise intended to profit from selling the people he enslaved to California after gold had been discovered there in 1849. An enslaved person in Virginia was worth $1,000, but in California, an enslaved person would be worth $3,000 to $5,000 digging gold.[20] Wise's plan, however, was thwarted when California joined the United States as a free state in the Compromise of 1850.[21]

Wise's plantation comprised 400 acres, and only about half were productive. Wise grew corn, oats, and sweet potatoes. Wise also raised livestock and maintained peach and pear orchards. His farm most likely profited $500 a year.[20]

Governor of Virginia

[edit]Wise returned to the United States in 1847 and resumed legal practice. He identified with the Jacksonian Democratic Party and was active in politics. A delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850, Wise opposed any reforms, insisting that the protection of slavery came first.[22] In the statewide election of 1855, Wise was elected Governor of Virginia as a Democrat, defeating Know-Nothing candidate Thomas S. Flournoy. He was the 33rd governor of Virginia, serving from 1856 to 1860, and the last Eastern Shore governor until Ralph Northam was elected in 2017.[23] Wise County, Virginia, was named after him when it was established in 1856.

Although he was visibly and unapologetically a defender of slavery, he opposed the imposition of the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution on Kansas Territory, as residents of Kansas had not approved it: "And why impose this Constitution of a minority on a majority? Cui bono? ["Who would that benefit?"] Does any Southern man imagine that this is a practicable or sufferable way of making a slave State?"[24]: 236 This stance played a large role in scuttling his preparations for a bid to challenge incumbent Robert M.T. Hunter in the Senate election in 1858, as Hunter was a supporter of the Lecompton Constitution.

Under the Virginia Constitution, governors cannot serve successive terms, so he was not a candidate for reelection in 1860.

John Brown

[edit]Wise was intensely interested in the case of John Brown, who briefly took over the town of Harpers Ferry. Wise refers several times to the need to "avenge the insulted honor of the state".[25] He said he found it humiliating that Brown's ragtag group could take Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and hold it for even one hour.[26] He traveled from Richmond to Harpers Ferry immediately and interviewed him at length. After returning to Richmond, in a widely reported speech, he praised Brown,[27][28][29] but he also called Brown and his men "murderers, traitors, robbers, insurrectionists," and "wanton, malicious, unprovoked felons."[30]

However, Governor Wise did many things to augment rather than reduce tensions: by insisting he was tried in Virginia and turning Charles Town into an armed camp full of state militia units. "At every juncture he chose to escalate rather than pacify sectional animosity."[31]

Some sources say that Wise signed John Brown's death warrant,[13] but this is incorrect; under Virginia law, the governor did not need to sign such a document, as Wise pointed out. After Brown was sentenced to death, Wise could have commutated his sentence to life imprisonment,[32] as was recommended to him by many people. The efforts to pressure Wise became so intense that, according to the Richmond Enquirer, he was offered the presidency in exchange for a pardon.[33][34][35] An unsigned letter from "a Green Mountain Boy" threatened Wise with assassination if Brown was executed,[36] and there was an unfunded project to kidnap Wise and sequester him at sea, on a boat, until Brown was released.[37]

One option Wise considered was to find Brown insane, which would have avoided the death penalty and sent him to an insane asylum. He had been given 19 affidavits from relatives and friends about the alleged madness of Brown and several of his relatives. This would have de-escalated the crisis, not turning Brown into abolition's martyr and hero, as he immediately became. However, after his interview with Brown in the engine house, Wise had said publicly that Brown was not insane at all. Before the trial, Brown had insisted that he did not want an insanity defense.

The prevailing political sentiment in Virginia was against de-escalation and strongly in favor of executing Brown. Wise was emerging as a national figure and had presidential ambitions. To take any action that would have prevented Brown's execution would have damaged Wise politically more than it could have helped him. On the contrary, the popularity Wise gained in the South for executing Brown, and the other captured members of his party led to Southern support for him as a presidential candidate in 1860.[18][38] Advertisements promoting Wise as a presidential candidate started to appear immediately after Brown's execution.[39]

John Brown's body had to pass through Philadelphia on the way to his burial site at the John Brown Farm, near Lake Placid, New York. As this provoked indignation among the many Southern medical students studying there, Wise sent them a telegram, assuring them of a hearty welcome if they came to Richmond or other Southern cities to complete their education. So many accepted that there was a special train to take two hundred of them from Philadelphia to Richmond, where they were addressed by Wise and enjoyed an elegant banquet.[40]

Secession crisis

[edit]In 1857, during the incoming Presidency of James Buchanan, Wise served as one of Buchanan's chief Southern advisors. Other Southern advisors to Buchanan included Senator John Slidell of Louisiana and Robert Tyler of Virginia. Tyler was the son of President John Tyler. Buchanan, although a Pennsylvania Democrat, held Southern sympathies, was a strict constructionist and detested abolitionists and "Black Republicans". [41]

During the secession crisis of 1860–61, Wise was a fervent advocate of immediate secession by Virginia. He was a member of the Virginia secession convention of 1861. Frustrated with the convention's inaction through mid-April, Wise helped plan actions by Virginia state militia to seize the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry and the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk. These actions were not authorized by the incumbent Governor Letcher or the militia's commanders.

These plans were pre-empted by the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12–14 and Lincoln's call on April 15 for troops to suppress the rebellion. After a further day and a half of the debate, the convention voted for secession 85 representatives in favor and 55 against.[42] On April 17, during the latter stage of the debate, Wise irrupted into the debate a gun in hand, declared Virginia was now at war with the United States, and that he would kill anyone who would try to shoot him for treason.[42]

Electoral history

[edit]- 1843: Wise was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives with 57.24% of the vote, defeating Whig Hill[43]

- 1850: Wise was elected delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1850

- 1855: Wise was elected governor of Virginia with 53.25% of the vote, defeating Thomas Stanhope Flournoy.

- 1861: Wise was elected delegate to the Secession Convention of 1861

Civil War

[edit]

After Virginia declared secession, Wise joined the Confederate States Army (CSA). Because of his political prominence and secessionist reputation, he was commissioned as a brigadier general, despite having no formal military training.[44] He was assigned to the western Virginia region, where his political support would be helpful. Brigadier General John B. Floyd, another former governor of Virginia, was also sent there. In the summer of 1861, Wise and Floyd feuded over who was the superior officer. At the height of the feud, General Floyd blamed Wise for the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Carnifex Ferry, stating that Wise refused to come to his aid.[45] The feud was not resolved until Virginia Delegate Mason Mathews, whose son Alexander F. Mathews was Wise's aide-de-camp, spent several days in the camps of both Wise and Floyd. Afterward, he wrote to President Jefferson Davis urging that both men be removed.[46][47] Davis subsequently removed Wise from his command in western Virginia.[45]

In early 1862, Wise was assigned to command the District of Roanoke Island, threatened by U.S. Navy forces. He fell ill with pleurisy and was not present for the Battle of Roanoke Island when U.S. Army soldiers stormed the island. He was blamed for the loss, but for his part, complained bitterly about inadequate forces to defend the island.[citation needed]

He commanded a brigade in the division of Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes on the New Market Road during the Seven Days Battles. For the rest of 1862 and 1863, he held various commands in North Carolina and Virginia.

In 1864, Wise commanded a brigade in the Department of North Carolina & Southern Virginia. His brigade defended Petersburg and was credited with saving the city at the First Battle of Petersburg and to an extent at the Second Battle of Petersburg. From June 17 until November 1864, Wise commanded the Military District of the City of Petersburg. He resumed command of his brigade in November and led it during the final stages of the Siege of Petersburg.

He was with Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House, where he fought bravely but urged Lee to surrender. With other Confederate officials, he was taken prisoner after the surrender.

Postwar political statements

[edit]Stating he was "a prisoner on parole", Wise summarized his view of slavery thus:

[T]he chief consolation I have in the result of the war is that slavery is forever abolished, that not only the slaves are in fact, at least freed from bondage, but that I am freed from them. Long before the war indeed, I had definitely made up my mind actively to advocate emancipation throughout the South. I had determined, if I could help it, my descendants should never be subject to the humiliation I have been subject to, by the weakness, if not the wickedness, of slavery; and while I can not recognize as lawful and humane the violent and shocking mode in which it has been abolished, yet I accept the fact most heartily as an accomplished one, and am determined not only to abide by it and acquiesce in it, but to strive by all the means in my power to make it benificent to both races and a blessing especially to our country. I unfeignedly rejoice in the fact, and am reconciled to many of the worst calamities of the war, because I am now convinced that the war was a special providence of God, unavoidable by the nation at either extreme, to tear loose from us a black idol from which we could never have been separated by any other means than those of fire and blood, sword and sacrifice.[48]

The Confederate Constitution (CC), adopted on March 11, 1861, banned the international slave trade. However, the CC prohibited passing laws that would make illegal "the right of property in negro slaves." According to historian Stephanie McCurry of Columbia University, the CC was a product of White men who held all the political power for themselves. Under the CC, Black people and women were not entitled to political power.[49]

Postbellum activities

[edit]

After the war, Wise resumed his law practice in Richmond and settled there for the rest of his life. In 1865 he tried to reclaim Rolleston, his plantation outside Norfolk, but was turned down by General Grant, considering that he did not make the Ironclad Oath.[50] He was told that he had abandoned that residence when he moved his family to another plantation at Rocky Mount, Virginia. The U.S. commander in Norfolk, Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry, appropriated it and other plantations for the Freedmen's Bureau to establish schools for formerly enslaved people and their children. Two hundred freedmen were said to be taking classes at Rolleston.[51] A picture of John Brown had been placed in the parlor. "The officers who confiscated the place found in the house among numerous other papers a plan of secession drawn up by Wise in 1857, and approved by Jeff Davis and several other prominent men In the South."[52] "It is said that ex-Governor Wise chafes a good deal and even foams at the mouth, because his house is used by old John Brown's daughter as a school-house for teaching little niggers."[53] Another report says that Brown's "daughters" were teachers in the school;[54] another says that no daughter was, although one of them was teaching contrabands near Norfolk and visited the mansion.[55]

Wise became a Republican and strong supporter of President Ulysses S. Grant. Unlike many other politicians, he did not emphasize his Confederate service or ever seek a pardon.[56]

While working in his law career, Wise wrote a book based on his public service, entitled Seven Decades of the Union (1872).

Death and legacy

[edit]Wise died in 1876 and was buried at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

His son Capt. Obediah Jennings Wise[57] died in 1862 under his father's command at Roanoke Island.[58] Another son, Richard, after service in the Confederate Army, studied medicine and taught chemistry. He also became a Virginia legislator and US Representative. A third son, John, served in the Confederate Army as a VMI cadet; he also later became an attorney and was elected as a US Representative. Both Richard Wise and John Wise were Republicans like their father. Another son, Henry A. Wise, Jr. (1834–1869), entered the ministry and assisted family friend Rev. Joshua Peterkin at St. James Episcopal Church in Richmond before resigning in 1859, a decade before his death.[59]

Henry A. Wise's grandson Barton Haxall Wise wrote a biography of the former governor, entitled The Life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia (New York, 1899).[60] Another grandson, the lawyer and soldier Jennings Cropper Wise (1881–1968, son of John Sergeant Wise), wrote The Early History of the Eastern Shore of Virginia and dedicated it to his grandfather. He quoted Governor Wise: "I have met the Black Knight with his visor down, and his shield and lance are broken."[61]

Counties were named in his honor in Virginia (Wise County, Virginia) and Texas (Wise County, Texas).

Archival material

[edit]The Wise family papers, 1836-1928 (350 items, available on microfilm), and the Henry A. Wise papers, 1850-1869 (90 items), are held by the Library of Congress. The numerous documents from his service as Governor are in the Library of Virginia.

Writing

[edit]- Wise, Henry A. (1881). Seven decades of the Union. The humanities and materialism, illustrated by a memoir of John Tyler, with reminiscences of some of his great contemporaries. The transition state of this nation – its dangers and their remedy. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weil, Julie Zauzmer; Blanco, Adrian; Dominguez, Leo. "More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation". Washington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Hambleton, James Pinkney (February 1, 2018). "A Biographical Sketch of Henry A. Wise : with a History of the Political Campaign in Virginia in 1855: to which is added a review of the position of parties in the Union, and a statement of the political issues: distinguishing them on the eve of the presidential campaign of 1856". Richmond, Va., J. W. Randolph. Retrieved February 1, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Washington College 1806–1865". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ McClelland, W.C. (1903). "A History of Literary Societies at Washington & Jefferson College". The Centennial Celebration of the Chartering of Jefferson College in 1802. Philadelphia: George H. Buchanan and Company. pp. 111–132. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c Renee M. Savits, "Blame It On Rio", UncommonWealth: Voices from the Library of Virginia, Library of Virginia, accessed December 2, 2020

- ^ Richards 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Jennings Cropper Wise, Col. John Wise of England and Virginia (1617–1695): His Ancestors and Descendants, Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1918; Digitized 2007 by University of California, p. 196 Archived January 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 20, 2008

- ^ 1850 US Census, St. George's Parish, Accomack Co, VA Archived October 28, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 5, 2008; John S. Wise, The End of an Era, New York: Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1899, p. 39; Documents of the South Collection, University of North Carolina Website Archived August 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed February 11, 2008

- ^ Simpson, p. 23

- ^ Simpson, p. 95.

- ^ Simpson, p. 222.

- ^ Idris Bowen, "Rolleston Hall, Virginia" Archived March 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The Rollestonian, Spring 2002, accessed February 2, 2008

- ^ a b . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- ^ Tunnell, Ted; Furgurson, Ernest B. (1998). "Ashes of Glory: Richmond at War". The Journal of Southern History. 64 (1): 17. doi:10.2307/2588092. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2588092.

- ^ "A Fatal Duel Between Members in 1838 – US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "A pair of dueling rifles reveal their story". National Museum of American History. March 10, 2016. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Cilley – Exhibit". cilley.net. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2018.