Appearance of the ancient Egyptians: Difference between revisions

fix |

→Ancient Egyptian view: restore, looks like deleted for pov reasons |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

<blockquote>As we know from their observant depictions of foreigners, the ancient Egyptians saw themselves as darker than Asiatics and Libyans, and lighter than the Nubians, and with different facial features and body types than any of these groups. They considered themselves, to quote Goldilocks, "just right." These indigenous categories are the only ones that can be used to talk about race in ancient Egypt without anachronism. Even these distinctions may have represented ethnicity as much as race: once an immigrant began to wear Egyptian dress, he or she was generally represented as Egyptian in color and features.<ref name="RothBridges">[http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/afrocent_roth.html Building Bridges to Afrocentrism]. By Ann Macy Roth</ref></blockquote> |

<blockquote>As we know from their observant depictions of foreigners, the ancient Egyptians saw themselves as darker than Asiatics and Libyans, and lighter than the Nubians, and with different facial features and body types than any of these groups. They considered themselves, to quote Goldilocks, "just right." These indigenous categories are the only ones that can be used to talk about race in ancient Egypt without anachronism. Even these distinctions may have represented ethnicity as much as race: once an immigrant began to wear Egyptian dress, he or she was generally represented as Egyptian in color and features.<ref name="RothBridges">[http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/afrocent_roth.html Building Bridges to Afrocentrism]. By Ann Macy Roth</ref></blockquote> |

||

According to Senegalese Egyptologist Aboubacry Moussa Lam, the Egyptians considered the [[Land of Punt]] as being their ancestral homeland.<ref>Aboubacry Moussa Lam, De l'origine égyptienne des Peuls, Paris: Présence Africaine / Khepera, 1993, p. 345</ref> Punt, was an ancient land south of Egypt accessible by way of the Red Sea. Its exact location has not been identified, but it is thought to have been somewhere in eastern [[Africa]], probably including northern [[Ethiopia]], [[Eritrea]], and east-northeast [[Sudan]] (southern [[Beja people|Beja]] lands).<ref>[http://www.maat-ka-ra.de/english/punt/puntlage.htm ''Where was Punt?''] Maat-ka-Ra Hatshepsut</ref> Temple reliefs at Deir el Bahari in W Thebes depict an Egyptian expedition to Punt in the reign of [[Hatshepsut]]. The Egyptians depicted Puntites to be |

According to Senegalese Egyptologist{{fact}} Aboubacry Moussa Lam, the Egyptians considered the [[Land of Punt]] as being their ancestral homeland.<ref>Aboubacry Moussa Lam, De l'origine égyptienne des Peuls, Paris: Présence Africaine / Khepera, 1993, p. 345</ref> Punt, was an ancient land south of Egypt accessible by way of the Red Sea. Its exact location has not been identified, but it is thought to have been somewhere in eastern [[Africa]], probably including northern [[Ethiopia]], [[Eritrea]], and east-northeast [[Sudan]] (southern [[Beja people|Beja]] lands).<ref>[http://www.maat-ka-ra.de/english/punt/puntlage.htm ''Where was Punt?''] Maat-ka-Ra Hatshepsut</ref> Temple reliefs at Deir el Bahari in W Thebes depict an Egyptian expedition to Punt in the reign of [[Hatshepsut]]. The Egyptians depicted Puntites to be similar in appearance to themselves but with darker skin.<ref>The Columbia Encyclopedia, Edition 6, 2000 p31655.</ref><ref>Shaw & Nicholson, op. cit., p.232</ref> The Egyptians also depicted the Greek [[Minoans]] similar to themselves [http://www.utexas.edu/courses/cc302k/Egypt/Egypt_images/9901280001.jpg]. |

||

==Academic view== |

==Academic view== |

||

Revision as of 21:17, 1 August 2007

There has been considerable controversy revolving around the "race" and appearance of the ancient Egyptians. Traditional depictions of ancient Egypt in the Western world have been rife with contradictions. Since the modern age of archaeological exploration, which began in the mid 19th century, a variety of images have been produced purporting to depict ancient Egyptians and their artifacts. In an era when many European nations actively were engaged in the Atlantic slave trade, notions of white supremacy and inherent black inferiority, even bestiality, were the norm. It is not surprising, therefore, that many of the images of dynastic Egypt made available to the general public were Europeanized. The black presence in ancient Egypt was treated as a footnote, and the commonly purveyed notion of blacks in pharaonic Egypt was that they were Nubian slaves of very European-looking Egyptian masters and mistresses.

With the excavation of the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt in 1922, a wave of what has been called "Egyptomania" swept the Western world, triggering renderings of ancient Egyptians in consumer goods, decorative art and in film. In the Cinema of the United States, particularly, white actors typically played the roles of ancient Egyptians. With few exceptions[1] black actors were cast, again, they generally appeared in the classic stereotypical role—that of the Nubian slave.

Today, the modern Western view holds that ancient Egypt was a multi-ethnic society, with many modern historians reluctant to make definitive claims about the skin color of Ancient Egyptians. Many Afrocentrists, however, insist that ancient Egyptians were "black African" peoples. They often emphasize that this black identity was strongest in early Egyptian history, and waxed and waned over time. Still, they maintain, Egypt remained essentially a black, African civilization throughout the dynastic era.

Defining race

In biology, some people use race to mean a division within a species. Thus, in certain fields it is used as a synonym for subspecies or, in botany, variety. In the case of honeybees, for instance, it stands as a synonym for subspecies. In this usage, race serves to group members of a species that have, for a period of time, become geographically or genetically isolated from other members of that species, and as a result have diverged genetically and developed certain shared characteristics that differentiate them from the others. Although these characteristics rarely appear in all members of the group, they are more marked in or appear more frequently than in the others.

The analysis of most social scientists conclude that the common notions of race are social constructs. These definitions of race are derived from custom, vary between cultures, and are described as imprecise and fluid. Often these definitions rely on phenotypic characteristics or inferred ancestry. The analysis of human genetic variation also provides insight into human population history and structure. The recent spread of humans from Africa has created a situation where the majority of human genetic variation is found within each human population. However, as a result of physical and cultural isolation of human groups, a significant subset of genetic variation is found between human groups. This variation is highly structured and therefore useful for distinguishing groups and placing individuals into groups for some scientists. Admixture and clinal variation between groups can be confounding to this kind of analysis of human variation. The relationship between social and genetic definitions of race is complex. Phenotypic racial classifications do not necessarily correspond with genotypical groups; some more than others. To the extent that ancestry corresponds to social definitions of race, groups identified by genetics will also correspond with these notions. Whether human population structure warrants the distinction of human 'races' is a matter of debate, with the majority of opinions varying between disciplines. Today, most biologists and anthropologists prefer the term population to race, avoiding the scientific stigma of predefined racial constructs.

Ancient writers

Many ancient writers commented of the 'racial affinities' of ancient Egyptians. While some held them to be people with 'black skins and woolly hair' similar to 'Kushites', others described them as 'medium toned' or similar to that of northern Indians. Greek historian Herodotus commented on a perceived relationship between the Colchians (from the modern Republic of Georgia in the Caucasus) and the Egyptians, he justifies this through his observation that these people had "black skins and kinky hair":

- Several Egyptians told me that in their opinion the Colchians were descended from soldiers of Sesostris. I had conjectured as much myself from two pointers, firstly because they have black skins and kinky hair and secondly, and more reliably for the reason that alone among mankind the Egyptians and the Ethiopians have practiced circumcision since time immemorial.[2]

Some interpretations have pointed out that Herodotus could have been speaking in relative terms, since the Colchians were noted as residing near the Black Sea, close to modern day Russia where there are virtually no dark skinned, woolly haired people today; There are also others who question whether or not Herodotus ever visited the Black Sea region in the first place.[3]

Other ancient writers testify however, that there indeed was an ancient population of dark skinned, woolly haired people residing in Colchis, giving at least some support to Herodotus' claim that they were left there by the armies of the legendary Sesostris after initial campaigns in the region. Indeed, there is further description from ancient writers describing the populations of Colchis in this fashion. A Greek poet named Pindar described the Colchians, whom Jason and the Argonauts fought, as being "dark skinned". Also around 350 to 400 AD, Church father Saint Jerome and Sophronius referred to Colchis as the "second Ethiopia" because of its 'black-skinned' population.[4]

Aristotle, who is noted to have probably not traveled to Egypt, stills makes his observation on the physical nature of the Egyptians and Ethiopians, be it through hearsay or actual contact. Here, Aristotle makes claim that skin color is somehow correlated to courage, and also gives his impression on why the Egyptians and Ethiopians are bowlegged and 'curly haired'.

- Too black a hue marks the coward as witness Egyptians and Ethiopians and so does also too white a complexion as you may see from women, the complexion of courage is between the two.

- Why are the Ethiopians and Egyptians bandy-legged? Is it because the bodies of living creatures become distorted by heat, like logs of wood when they become dry? The condition of their hair supports this theory; for it is curlier than that of other nations, and curliness is as it were crookedness of the hair.[5]

Ammianus Marcellinus (325/330-after 391) was a Greco-Roman historian who also gave his own brief observations.

- the men of Egypt are mostly brown and black with a skinny and desiccated look.[6]

Ancient writers have also made comparisons between ancient Egyptians and northern Indians of the time.

Strabo (c. 64 BC – AD 24):

- As for the people of India, those in the south are like the Aethiopians in colour, although they are like the rest in respect to countenance and hair (for on account of the humidity of the air their hair does not curl), whereas those in the north are like the Aegyptians.[7]

Arrian (c. 86 - 146 AD) (Indica 6.9):

- The appearance of the inhabitants is also not very different in India and Ethiopia: the southern Indians are rather more like Ethiopians as they are black to look on, and their hair is black; only they are not so snub-nosed or woolly-haired as the Ethiopians; the northern Indians are most like the Egyptians physically.[8]

The above writings of Strabo and Arrian were drawn from the earlier accounts of Nearchus (c. 360 - 300 BC), Megasthenes (c. 350 - 290 BC) and Eratosthenes (276 - 195 BC).[9]

It is important to note however, that phenotypes differ among populations and skin color varies and is highly adaptive, therefore alone, they're not good indicators of any concept of 'race'.[10] In some cases, ancient textual sources can be extremely reliable, however, in cases like these bioanthropologist Shomarka Keita warns us that interpretation is highly dependent on stereotyped thinking, and in his words, "the ancient writers were not doing population biology", and given that as a result, all of this should be taken with 'a grain of salt'.

Ancient Egyptian view

The Egyptians considered themselves part of a distinct group, separate from their neighbors.[11] The ancient Egyptians thought of themselves simply as Egyptian people. In their wall paintings, they distinguished themselves from Nubian, Lybian, Semitic, Berber, and Eurasian peoples. Egyptologist Ann Macy Roth[12] writes:

As we know from their observant depictions of foreigners, the ancient Egyptians saw themselves as darker than Asiatics and Libyans, and lighter than the Nubians, and with different facial features and body types than any of these groups. They considered themselves, to quote Goldilocks, "just right." These indigenous categories are the only ones that can be used to talk about race in ancient Egypt without anachronism. Even these distinctions may have represented ethnicity as much as race: once an immigrant began to wear Egyptian dress, he or she was generally represented as Egyptian in color and features.[13]

According to Senegalese Egyptologist[citation needed] Aboubacry Moussa Lam, the Egyptians considered the Land of Punt as being their ancestral homeland.[14] Punt, was an ancient land south of Egypt accessible by way of the Red Sea. Its exact location has not been identified, but it is thought to have been somewhere in eastern Africa, probably including northern Ethiopia, Eritrea, and east-northeast Sudan (southern Beja lands).[15] Temple reliefs at Deir el Bahari in W Thebes depict an Egyptian expedition to Punt in the reign of Hatshepsut. The Egyptians depicted Puntites to be similar in appearance to themselves but with darker skin.[16][17] The Egyptians also depicted the Greek Minoans similar to themselves [2].

Academic view

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2007) |

Ancient Egypt was thought by many scholars to have been a melting pot of various Saharan, Nilotic, and Levantine peoples since earliest times,[18][19] but no one in Egyptology today believes that there were any pre-Hellenic Egyptians who looked anything like modern Europeans. The archaeologist Bruce Williams commented that few Egyptians, ancient or modern, would have been able to get a meal at a white lunch counter in the American South during the 1950s.[13] The ancient Egyptians have been described by several studies as having a “Negroid” body plan that clusters near those of tropical Africans.[20][21]

Cheikh Anta Diop performed a series of the tests on Egyptian mummies to determine melanin levels and concluded that Egyptians were dark-skinned and part of the "Negro race". Diop notes criticisms of these results that argue that the skin of most Egyptian mummies, tainted by the embalming material, are no longer susceptible of any analysis. Diop contends the position that although the epidermis is the main site of the melanin, the melanocytes penetrating the derm at the boundary between it and the epidermis, even where the latter has mostly been destroyed by the embalming materials, show a melanin level which is non-existent in the "white-skinned races".[22] However, Diop does not describe any tests that verify his claims that melanin is "non-existent" among the "white-skinned races", nor provide evidence supporting his assertion that the absence of melanin in the epidermis is due to embalming techniques. Diop innovated the development of the melanin dosage test which was later adopted by forensic investigators to determine the racial identity of badly burnt accident victims.[23]

Mummy reconstructions

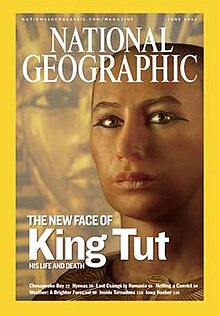

King Tutankhamun

King Tutankhamun is the most famous of the pharaohs, and his mummy is estimated to be about 3000 years old. In 2005, three teams of scientists (Egyptian, French and American), in partnership with the National Geographic Society, developed a new facial likeness of Tutankhamun. The Egyptian team worked from 1,700 three-dimensional CT scans of the pharaoh's skull. The French and American teams worked plastic molds created from these – but the Americans were never told whom they were reconstructing.[24] All three teams created silicone busts of their interpretation of what the young monarch looked like. In the end, they identified the skull as:

that of a male, 18 to 20 years old, with Caucasoid features.[24]

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to criticism of the King Tut reconstructions:

- The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We'll never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100 percent certainty. ... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion.[25]

The French team's reconstruction specifically however, has sparked considerable criticism. Afrocentrists criticize the French team's claim that they selected the skin tone by taking a color from the middle of the range of skin tones found in the population of Egypt today.[26] They claim that these features do not reflect the prevalent eye or skin color of either ancient dynastic Egypt or present-day Egyptians . They further argue that many representations of Tut portray him with red-brown to dark-brown skin and dark eyes, and that the teams should have used these as references in assigning eye and skin color.

In comparison to the 2005 reconstruction, the earlier 2002 Discovery Channel reconstruction showed a darker skin tone, among other differences.[27]

Difficulties of forensic reconstruction

Although their methodologies are objective, forensic anthropologists agree that attempts to apply criteria from craniofacial anthropometry sometimes can yield seemingly counterintuitive results, depending upon the weight given to each feature. For example, their application can result in finding some East and South Indians to have "Negroid" cranial/facial features and others to have "Caucasoid" cranial/facial features, for example, while Ethiopians, Somalis, and some Zulus have "Caucasoid" skulls, and the Khoisan of southwestern Africa have skulls distinct from many other sub-Saharan Africans that resembles "Mongoloid" skulls.

These seeming contradictions, however, are related to the vagaries of racial classification, particularly of ethnically diverse or miscegenated populations, as exist in Africa and the Indian subcontinent. Cranial analysis is still used by some forensic scientists to determine the identity and geographic ethnic origin of human remains, even though the accuracy of ethnicity-related conclusions drawn from cranial analysis is not absolute -- particularly when treating populations possessing varying degrees of "racial", or ethnic, admixture. Though modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy based on CT data from his mummy, but due to lack of facial tissue and embalming issues, correctly determining his skin tone, nose width, and eye color is nearly impossible.[28] The problem is not a lack of skill on the part of Ancient Egyptians. Egyptian artisans distinguished accurately among different ethnicities, but sometimes depicted their subjects in totally unreal colors, the purposes for which aren't completely understood. Thus no absolute consensus on the skin tone and various other features of reconstructed mummies such as Tutankhamun is possible.

Art and architecture

Egyptian art is not considered a reliable source for what ancient Egyptians looked like for several reasons:

- Egyptian art is often very faded and/or eroded.

- Egyptians are often portrayed in impossible shapes and colors. For example, in some paintings they are green.

- The skin color of a single individual varies widely from one portrayal to the next. For example, Tutankhamen is jet black in one rendering, and medium brown in another.

- Skin color was not such a significant political or social factor in that time as it is now.

- It is sometimes difficult to know if the artist is aiming for realism, or is actually painting an original or mythical conception.

- There is sometimes debate over whether it is an Egyptian, a slave, or a foreigner that is being portrayed.

- Even if an individual portrayal was known to be accurate (there is no such case), even that would do nothing to indicate the appearance of the ancient Egyptian populace as a whole.

- According to archaeologist Kathryn Bard, it was conventional in Egyptian art to paint men in a dark-red ochre and women in a light-yellow ochre to distinguish them.

-

A wooden statue head of Queen Tiye, thought to be Tutankhamun's Grandmother, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection.

-

Fragmentary statue of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun's father. On display at the Cairo Museum.

-

Plaster face of a young Amarna-era woman, thought to represent Queen Kiya, the likely mother of Tutankhamun. On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

-

Canopic jar depicting an Amarna-era Queen, usually identified as being Queen Kiya. On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

-

The iconic image of Queen Nefertiti, the step-mother of Tutankhamen, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection.

-

Another statue head depicting Nefertiti, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection.

-

Fragmentary statue thought to represent Ankhesenamun, sister and wife to Tutankhamun, on display at the Brooklyn Museum.

-

Statue of an unnamed Amarna-era princess, a likely sister (or step-sister) to Tutankhamun. Part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection.

The Great Sphinx of Giza

Over the centuries, numerous writers and scholars have recorded their impressions and reactions upon seeing the Great Sphinx of Giza. French scholar Constantin-François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney visited Egypt between 1783 and 1785 . He is one of the earliest known Western scholars to remark upon what he saw as its "typically Negro" countenance.

"...[The Copts] all have a bloated face, puffed up eyes, flat nose, thick lips; in a word, the true face of the negro. I was tempted to attribute it to the climate, but when I visited the Sphinx, its appearance gave me the key to the riddle. On seeing that head, typically negro in all its features, I remembered the remarkable passage where Herodotus says: 'As for me, I judge the Colchians to be a colony of the Egyptians because, like them, they are black with woolly hair. ...'".[29]

Upon visiting Egypt in 1849, French author Gustave Flaubert echoed de Volney's observations. In his travelog chronicling his trip, he wrote:

We stop before a Sphinx; it fixes us with a terrifying stare. Its eyes still seem full of life; the left side is stained white by bird-droppings (the tip of the Pyramid of Khephren has the same long white stains); it exactly faces the rising sun, its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s, its neck is eroded; from the front it is seen in its entirety thanks to great hollow dug in the sand; the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick….[30]

In his work The Negro, published in 1915, W.E.B. Du Bois observed:

The great Sphinx at Gizeh, so familiar to all the world, the Sphinxes of Tanis, the statue from the Fayum, the statue of the Esquiline at Rome, and the Colossi of Bubastis all represent black, full-blooded Negroes and are described by Petrie as "having high cheek bones, flat checks, both in one plane, a massive nose, firm projecting lips, and thick hair, with an austere and almost savage expression of power."

and:

Blyden, the great modern black leader of West Africa, said of the Sphinx at Gizeh:"Her features are decidedly of the African or Negro type, with 'expanded nostrils.' If, then, the Sphinx was placed here—looking out in majestic and mysterious silence over the empty plain where once stood the great city of Memphis in all its pride and glory, as an 'emblematic representation of the king'--is not the inference clear as to the peculiar type or race to which that king belonged?"[31]

In 1992, the New York Times published a letter to the editor submitted by then Harvard professor of Orthodontics Sheldon Peck in which he commented on a study of the Giza sphinx conducted by New York City Police Department senior forensics artist Frank Domingo. Peck Wrote:

The analytical techniques…Detective Frank Domingo used on facial photographs are not unlike methods orthodontists and surgeons use to study facial disfigurements. From the right lateral tracing of the statue's worn profile a pattern of bimaxilliary prognathism is clearly detectable. This is an anatomical condition of forward development in both jaws, more frequently found in people of African ancestry than in those from Asian or Indo-European stock. [32] New York Times

Kmt

| km biliteral | km.t (place) | km.t (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

One of the many names for Egypt in ancient Egyptian is km.t (read "Kemet"), meaning "black land". More literally, the word means "something black". The use of km.t in terms of a place is thought generally to be in contrast to the "deshert" or "red land", e.g. the desert west of the Nile valley. Egypt for millennia depended on the flooding of the Nile to bring fertility to the land, and the resulting soil was very black.[33] Likewise, one of the names the Egyptians used for themselves is Kmt. Raymond Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian translates it into "Egyptians", as do most sources.[34] However, Aboubacry Moussa Lam translates it into "the Blacks"[35].

Alleged Eurocentrism in Egyptology

Egyptology performed during the colonial eras is regarded by Egyptologists today as having had a racial prejudice against dark-skinned Africans.[13] Afrocentrists have been at the forefront of criticizing the prejudices of Egyptology performed during these eras.

In an interview delivered in Guadeloupe in 1983, Cheikh Anta Diop, denounced colonial Egyptology as prejudiced against black historical accomplishments. Egyptologists, according to Cheikh Anta Diop, knew very well that the Egyptians were Black people. But the fact that Africans were colonized, he argued, made it difficult to admit that they were the creators of the Egyptian civilization. He quoted, for example, Champollion-Figeac who said that “black skin and wholly hair don’t make someone to belong to the Black race”. Diop also mentioned Breasted and Maspero as people who falsified intentionally, along with Champollion-Figeac, the history of Egypt. In his book, Egitto e Nubia, Maurizio Damiano-Appia wrote that for many Egyptologists of the past, and even of today, Egypt was the creation of a "white race." Appia alleges that Eurocentrism, mainly of Anglo Saxon orientation, was at the base of this false idea. [36]. Aboubacry Moussa Lam, in his book L’affaire des momies royales. La vérité sur la reine Ahmès-Nefertari, argued that Egyptian mummies were falsely described as belonging to people with white skin.[37].

Basil Davidson, who does not identify as an Afrocentrist, has also denounced what he sees as the blatant falsification of the Egyptian history by some Western scholars. He agrees that the Egyptians were Black people and originated from the south and the west.[38] [39]

Egyptology today does not claim that the ancient Egyptians were white, and instead aims to study them without any consideration of "race" whatsoever. But in doing so, Egyptology is trying to conceal its colonial heritage. The continuing translation of "Kmt" into "Egyptians" rather than "Blacks" is one of the many examples[40]. As to their origins, Egyptians were primarily from the south, then joined by people fleeing the desertification of the Sahara; and as to the color of their skin, Davidson firmly believes that they were "Black people".[41]

Myths

Cleopatra

The claim that Cleopatra, the last Pharaoh of Egypt, was of African origin has been espoused by several Afrocentric academics, and has enjoyed a notable degree of acceptance within the African-American community.[42] Cleopatra, however, was of Hellenistic origin. Mary Lefkowitz argues that Afrocentric scholars are to blame for the proliferation of this myth. However, according to Professor of African American Studies at Temple University, Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, this is but one of many trivial issues and he states:

- I think I can say without a doubt that Afrocentrists do not spend time arguing that either Socrates or Cleopatra were black. I have never seen these ideas written by an Afrocentrist nor have I heard them discussed in any Afrocentric intellectual forums. Professor Lefkowitz provides us with a hearsay incident which she probably reports accurately. It is not an Afrocentric argument.[43]

Lefkowitz actually does cite examples of Afrocentric scholars who have made such claims. One such example she supplies is a chapter entitled "Black Warrior Queens" published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of the Journal of African Civilization series. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers. In any event, Afrocentrists strongly contend that this matter is of inane interest and is not an argument often pursued, most concede to the fact that Cleopatra was not of native Egyptian descent.

Extra-terrestrials

Some books have claimed that ancient Egyptians weren't even of the human race. The African-American Baseline Essays refer to "the extra-terrestrial origin of the Nile." This myth has no basis in fact.

White Egypt

The hypothesis that the ancient Egyptians were a predominantly "white" civilization was viable in the heyday of European colonialism, but is today regarded as (racist) pseudoscience. However, several neo-Nazi and racist groups such as Stormfront still hold this myth to be true, holding that ancient Egypt was a "Nordic desert empire."[44] This view enjoys no support whatsoever among researchers of ancient Egypt for the simple reason that there is no evidence for it, and enormous evidence against it.

References

- ^ video

- ^ Herodotus, Book II, 104

- ^ Did Herodotus Ever Go to the Black Sea? JSTOR

- ^ Cushites, Colchians, and Khazars JSTOR

- ^ Physiognomics, Vol. VI, 812a - Book XIV, p. 317

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Book XXII, para 16 (23)

- ^ Strabo Book XV, Chapter 1

- ^ Indica 6.9

- ^ Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 4). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 8120804058.

- ^ American Anthropological Association Statement on "Race" (May 17, 1998)

- ^ "Were the Ancient Egyptians Black or White?"

- ^ Ann Macy Roth New York University, Arts & Science

- ^ a b c Building Bridges to Afrocentrism. By Ann Macy Roth

- ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, De l'origine égyptienne des Peuls, Paris: Présence Africaine / Khepera, 1993, p. 345

- ^ Where was Punt? Maat-ka-Ra Hatshepsut

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Edition 6, 2000 p31655.

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson, op. cit., p.232

- ^ [Irish, et al. 2006.]

- ^ [Zakrzewski, et al. 2007.]

- ^ (Robins, 1983)

- ^ (Zakrzweski, 2003)

- ^ Origin of the Ancient Egyptians by Cheikh Anta Diop

- ^ http://www.webzinemaker.com/admi/m7/page.php3?num_web=27310&rubr=3&id=290477

- ^ a b

Handwerk, Brian (May 11, 2005). "King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Henerson, Evan (June 15, 2005). "King Tut's skin color a topic of controversy". U-Daily News - L.A. Life. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ King Tut: African or European

- ^ Discovery: King Tut (2002)

- ^ King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction National Geographic News

- ^ Cheikh Anta Diop argues that many Ancient Egyptians were Black Africans; the Greek debt to Egypt

- ^ The Sphinx of Giza

- ^ William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, The Negro (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1915)

- ^ Sphinx May Really Be a Black African

- ^ [1]

- ^ Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, De l'origine égyptienne des Peuls, Paris: Présence Africaine / Khepera, 1993, p. 181.

- ^ Maurizio Damiano-Appia, Egitto e Nubia, Con la collaborazione di Francesco L. Nera, Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, L'affaire des momies royales. La vérité sur la reine Ahmès-Nefertari, Paris: Khepera / Présence Africaine, 2000.

- ^ Basil Davidson. The Nile windows media video.

- ^ links to Basil Davidson's videos

- ^ Rainer Hannig, Die Sprache der Pharaonen, Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1995, p. 883

- ^ History of Africa to 1885

- ^

- "Was Cleopatra Black", from Ebony magazine, February 1st, 2002.

- "Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks", from the St. Louis Dispatch, February 14th, 1994.

- "A Professor's Collision Course", from The Washington Post, June 11th, 1996.

- ^ Race in Antiquity: Truly Out of Africa By Molefi Kete Asante

- ^ MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE Stormfront

See also

Population history of ancient Egypt

External links

- National Geographic's Reconstruction of Tutankhamun

- Earlier Reconstruction of Tutankhamun - Currently on display in the UK at the Science Museum:

- Reconstruction of Nefertiti

- Basil Davidson's videos