Claimed moons of Earth: Difference between revisions

m Date maintenance tags and general fixes |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Notability|date=March 2009}} |

|||

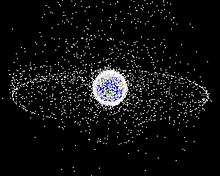

[[Image:Debris-GEO1280.jpg|thumb|Earth has many temporary artificial satellites in the form of Space debris, This populations seen from outside [[geosynchronous orbit]]. However, no permanent natural satellites other then the Moon have been found]] |

[[Image:Debris-GEO1280.jpg|thumb|Earth has many temporary artificial satellites in the form of Space debris, This populations seen from outside [[geosynchronous orbit]]. However, no permanent natural satellites other then the Moon have been found]] |

||

'''Earth's second moon''' is a name that has been given to many theorized Earth orbiting objects and at least one real object over the years. In recent years the periodic inclusion [[planetoid]] [[3753 Cruithne]] (confirmed in 1997) has been given the moniker "Earth's second moon"<ref> "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, [[Jean Meeus]], chapter 38: ''Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit'' </ref>, although it orbits the sun<ref name="space.com">{{Cite web|last=Lloyd|first=Robin|publisher=Space.com|url=http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/solarsystem/second_moon_991029.html|title=More Moons Around Earth?}}</ref><ref> "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, [[Jean Meeus]], chapter 38: ''Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit''</ref>. |

'''Earth's second moon''' is a name that has been given to many theorized Earth orbiting objects and at least one real object over the years. In recent years the periodic inclusion [[planetoid]] [[3753 Cruithne]] (confirmed in 1997) has been given the moniker "Earth's second moon"<ref> "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, [[Jean Meeus]], chapter 38: ''Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit'' </ref>, although it orbits the sun<ref name="space.com">{{Cite web|last=Lloyd|first=Robin|publisher=Space.com|url=http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/solarsystem/second_moon_991029.html|title=More Moons Around Earth?}}</ref><ref> "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, [[Jean Meeus]], chapter 38: ''Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit''</ref>. |

||

| Line 69: | Line 68: | ||

==Near Earth objects and Quasi-satellites== |

==Near Earth objects and Quasi-satellites== |

||

===Quasi-Satellites=== |

===Quasi-Satellites=== |

||

[[Image:Lagrange Horseshoe Orbit.jpg|thumb|right| |

[[Image:Lagrange Horseshoe Orbit.jpg|thumb|right|200px|'''Figure 1.''' Plan showing possible orbits along gravitational contours (Not to scale)]] |

||

Several [[asteroid]]s such as [[3753 Cruithne]], [[54509 YORP]], {{mpl|(85770) 1998 UP|1}}, {{mpl|2002 AA|29}}, and [[2003 YN107|{{mp|2003 YN|107}}]]) are known to occupy [[horseshoe orbits]] with respect to [[Earth]], and may become [[Quasi-satellite]]s. [[2004 GU9]] is another quasi-moon, similar to Cruithne but has a [[corkscrew orbit]]. |

Several [[asteroid]]s such as [[3753 Cruithne]], [[54509 YORP]], {{mpl|(85770) 1998 UP|1}}, {{mpl|2002 AA|29}}, and [[2003 YN107|{{mp|2003 YN|107}}]]) are known to occupy [[horseshoe orbits]] with respect to [[Earth]], and may become [[Quasi-satellite]]s. [[2004 GU9]] is another quasi-moon, similar to Cruithne but has a [[corkscrew orbit]]. |

||

Revision as of 18:55, 13 March 2009

Earth's second moon is a name that has been given to many theorized Earth orbiting objects and at least one real object over the years. In recent years the periodic inclusion planetoid 3753 Cruithne (confirmed in 1997) has been given the moniker "Earth's second moon"[1], although it orbits the sun[2][3].

Theoretical ideas about a "second moon" have usually been poorly founded and Generally dis-proven[4]. Many types of Near-Earth objects have been discovered including some Quasi-satellites. While many genuine scientific searches for second moons were undertaken in the 19th and 20th centuries, it has also been the subject of many non-scientific proposals and possible hoaxes.

There have been large generic searches for small moons, actual proposals or claimed sightings of specific objects in orbit, and finally, analysis and searches for those proposed objects. All three of these have not confirmed a permanent natural satellite.

History

"We found new dynamical channels through which free asteroids become temporarily moons of Earth and stay there from a few thousand years to several tens of thousands of years,"

Fathi Namouni, 1999 [5]

Care must be taken to differentiate between general searches for objects around the planet, and actual proposals for specific objects in a certain orbit. Claimed sightings of these objects must be further differentiated, from the hypothesis drawn from them and whatever may or may not have been seen.

The first major claim of a second moon was a report in 1846 by Toulouse Observatory, but further scientific observations and study did not confirm that proposed object. Other specific claims of objects and orbits that suggested to be second moons have also failed to be confirmed.

Proposed moons & claimed sightings

There have been several cases of people proposing second earth moons, but only one was by a professional astronomer at observatory.

Toulouse Observatory sighting & Petit's moon

- Toulouse Observatory's second moon

In 1846, French astronomer Frédéric Petit, director of the observatory at Toulouse Observatory, France, announced that he had discovered a second moon in an elliptical orbit around the Earth. It was claimed to be reported by Lebon and Dassier also at Toulouse, and Lariviere at Artenac Observatory, during the early evening of March 21, 1846.[6] Petit's proposed that this second moon had an elliptical orbit, a period of 2 hours 44 minutes, with 3570 km apogee and 11.4 km perigee. [6] This claim was soon dismissed by his peers. [7] The 11.4 km perigee is only 37401 feet altitude, which would have resulted it in going through earth's atmosphere.

- Petit's paper

Frédéric Petit became obsessed with the 1846 observations and ended up publishing another paper 15 years later, basing the second moon's existence on perturbations the existing lunar moon. [6] This second moon hypothesis was not-confirmed either, however the the concept was taken up by science fiction writer Jules Verne, who included a fictional moon based on Petit's second proposal for a second moon. [6] This fictional moon, however was not exactly based based on the Toulouse observations or Petit's propsal at a technical level, and orbit suggested by Verne was mathematically incorrect. [6] Unfortunately, Frédéric Petit died in 1865, and so was not alive to offer a response to Verne's fictional moon [8]

Waltemath's moons

"Perhaps it is also the moon presiding over this lunacy"

Science on Waltemath's Warhafter Wetter-und Magnet Mond in 1898 [9]

Dr. Georg Waltemath searched for secondary moons based on the hypothesis that something was effecting the Moon's orbit. [10] In 1898, Hamburg scientist Dr. Georg Waltemath announced he had located a second moon[11] inside a system of tiny moons orbiting the Earth.[12] Waltemeth is reported as saying, "Sometimes, it shines at night like the sun but only for an hour or so"[13], later quoted by the The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. [14]

Waltemath gave the description of one of the proposed moons as being 1.03 million km from earth (640,000 miles), with a diameter of 700 km (435 miles), an orbital period 119 days, and a synodic period 177 days.[6] He also said it did not reflect enough sunlight to be observed without a telescope, unless viewed at certain times, and made several predictions as to when it would appear [15] However, after the failure of a corroborating observation of Waltemath's moons by the scientific community, these objects were discredited. Especially problematic was a failed prediction that they would be observable in February 1898 [6] Waltemath proposed more moons, according to a mention in August 1898 issue of Science. The third moon was closer then the first, 746 km in diameter, and he called it "Warhafter Wetter-und Magnet Mond". [9]

Waltemath's moons later inspired the creation of a Astrological 'dark' earth moon in 1918, including a claim of actual observation of one of them. [16] (see History of astrology)

1900s

- W. Spill's moon

In 1926, the science journal Die Sterne published the findings of an amateur German astronomer named W. Spill, who claimed to have successfully viewed a second moon orbiting the earth.[14] [14]

- J. Bargby's satellites

In the late 1960s John Bargby claimed to have observed over ten small natural satellites of the Earth, but this was not confirmed.[6]

General Surveys

- Pickering

William Henry Pickering (1858-1938), studied the possibility of a second moon and made general search ruling out the possibility of many types of objects by 1903. [17] Many years later his article "A Meteoritic Satellite" in Popular Astronomy in 1922 resulted in increased searches for small natural satellites by amateur astronomers. [6] Pickering had also proposed the Moon itself had broken off from earth. [18]

- Clyde Tombaugh survey

Clyde Tombaugh, the discover of the (then called) planet Pluto, was sponsored by the United States Army Office of Ordnance Research to do a search for near earth asteroids. Another public statement was made on the search in March 1954, emphasizing the rationales for the search.[19] However, according to Donald Keyhoe, later director of the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena (NICAP), the real reason for the sudden search was because two near-Earth orbiting objects had been picked up on new long-range radar in the summer of 1953, according to his Pentagon source. By May 1954, Keyhoe made public statements that his sources told him the search had indeed been successful, and either one or two objects had been found.[20] However, the story didn't really break until August 23, 1954, when Aviation Week magazine stated that two natural satellites had been found only 400 and 600 miles out. However, both LaPaz and Tombaugh were to issue public denials that anything had been found. The October 1955 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine reported:

- "Professor Tombaugh is closemouthed about his results. He won't say whether or not any small natural satellites have been discovered. He does say, however, that newspaper reports of 18 months ago announcing the discovery of natural satellites at 400 and 600 miles out are not correct. He adds that there is no connection between the search program and the reports of so-called flying saucers."[21]

At a meteor conference in Los Angeles in 1957, Tombaugh reiterated that his four year search for "natural satellites" had been unsuccessful.[22] In 1959, Tombaugh was to issue a final report stating that nothing had been found in his search.

21st century

Although a permanent second earth moon did not exist, there are various types of Near-Earth object. Related subjects include Natural satellites, Quasi-satellite, Earth-crosser asteroids, and Co-orbital moons. Examples of less traditional objects include 2006 RH120 or 3753 Cruithne.

Near Earth objects and Quasi-satellites

Quasi-Satellites

Several asteroids such as 3753 Cruithne, 54509 YORP, (85770) 1998 UP1, 2002 AA29, and 2003 YN107) are known to occupy horseshoe orbits with respect to Earth, and may become Quasi-satellites. 2004 GU9 is another quasi-moon, similar to Cruithne but has a corkscrew orbit.

Other objects include 6Q0B44E, is a piece of man-made space debris in orbit around the Earth and 2006 RH120, a small meteoroid originally thought to be space debris.

- 3753 Cruithne

The asteroid 3753 Cruithne has a "remarkable orbit", and is a periodic inclusion planetoid and sometimes called Earth's second moon, although it orbits the sun.[2] [23]Its orbital path and Earth's do not cross, and its orbital plane is currently tilted to that of the Earth by 19.8°. Cruithne, having a maximum opposition magnitude of +15.8, is fainter than Pluto and would require at least a 12.5 inch reflecting telescope to be seen.[24][25]

- 2002 AA29

The 2002 AA29 The asteroid spends most of its time following a "horseshoe orbit" that takes it near the Earth every 95 years as it follows Earth's orbit around the Sun. In about 600 years, it will appear to circle Earth in a quasi-satellite orbit. Calculations suggest 2002 AA29 was in such a quasi-satellite orbit between about 550–600 A.D.; but the object is too small to have been observed visually by the astronomers of that era. 2003 YN107 has a similar orbit.

Near-Earth objects

Objects in space sometimes travel near by or collide with earth, and some even pass through the atmosphere without being destroyed. See Near-Earth_objects#Close_approaches Close approaches for more about near earth objects, or Earth-crosser asteroid.

For example, On March 18, 2004, LINEAR announced a 30 meter asteroid 2004 FH, which would pass the Earth that day at only 42,600 km (26,500 miles), about one-tenth the distance to the moon, and the closest miss ever noticed. They estimated that similar sized asteroids come as close about every two years[26]

For example On March 31, 2004, two weeks after 2004 FH, meteoroid 2004 FU162 set a new record for closest recorded approach, passing Earth only 6,500 km (4,000 miles) away (nearly one-sixtieth of the distance to the Moon). Because it was very small (6 meters/20 feet), FU162 was detected only hours before its closest approach.

- Earth-grazers

The The Great Daylight 1972 Fireball, was a well observed Earth-grazing meteor that passed through the atmosphere then back out into space. [27]. The meteoroid's 100 second passage through the atmosphere reduced its velocity by about 800 metres per second (2,600 ft/s) and the whole encounter significantly changed its orbital inclination from 15 degrees to 8 degrees.[28]

Earth's "second moon" in literature

- Jules Verne's novel, From the Earth to the Moon helped to popularize Frederic Petit's original theory of a secondary moon.

- Samuel R. Delany's 1975 novel Dhalgren features an Earth which mysteriously acquires a second moon.

- Eleanor Cameron's Mushroom Planet novels for children (the first being The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet) are set on a tiny, habitable second moon called Basidium in an invisible orbit 50,000 miles from Earth.

- Petit & Jules Verne's fictional moon

Petit's second moon was not accepted, but he continued to search explanations resulting another proposal 15 years later. [6] The writer Jules Verne learned of Petit's second proposals for a second moon theory. He became intrigued by the idea and made use of it in his 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon. [7] The explosive popularity of Jule's Verne's book in the 19th century triggered many amateur astronomers to search for second moons around earth although Petit did not live to see this, having passed away in 1865.

References

- ^ "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, Jean Meeus, chapter 38: Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit

- ^ a b Lloyd, Robin. "More Moons Around Earth?". Space.com.

- ^ "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, Jean Meeus, chapter 38: Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit

- ^ /passingstrangeness.wordpress.com - "Earth’s Other Moon" 2009 January 24

- ^ http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/solarsystem/second_moon_991029.html More Moons Around Earth? Its Not So Loony, By Robin Lloyd Senior Science Writer posted: 11:42 am ET 29 October 1999

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schlyter, Paul. nineplanets.org

- ^ a b Moore, Patrick. The Wandering Astronomer. CRC Press, 1999b, ISBN 0750306939 , see

- ^ http://www.imcce.fr/fr/ephemerides/astronomie/Promenade/pages5/549.html History of the Toulouse Observatory

- ^ a b http://books.google.com/books?id=WX0CAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA185&dq=%22Georg+Waltemath%22#PRA1-PA185,M1 Science N8 Volume VIII No. 189, Page 185

- ^ Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World on All Important Current Topics Published by Public Opinion Co., 1898; "The Alleged Discovery of a Second Moon", p369

- ^ Observatoire de Lyon. Bulletin de l'Observatoire de Lyon. Published in France, 1929, p. 55.

- ^ Bakich, Michael E. The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 146, ISBN 0521632803 , see

- ^ Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World on All Important Current Topics Published by Public Opinion Co., 1898; "The Alleged Discovery of a Second Moon", p369

- ^ a b c Bakich, Michael E. The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 148, ISBN 0521632803 , see

- ^ Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World on All Important Current Topics Published by Public Opinion Co., 1898; "The Alleged Discovery of a Second Moon", p369

- ^ Sepharial, A. The Science of Foreknowledge: Being a Compendium of Astrological Research, Philosophy, and Practice in the East and West.; Kessinger Publishing (reprint), 1997, pp. 39-50; ISBN 1564597172 , see

- ^ "On a photographic search for a satellite of the Moon", Popular Astronomy, 1903

- ^ Pickering, W.H (1907), "The Place of Origin of the Moon - The Volcani Problems", Popular Astronomy: 274–287

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Armed Forces Seeks "Steppingstone to Stars"", Los Angeles Times, 1954-03-04

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "1 or 2 Artificial Satellites Circling Earth, Says Expert", San Francisco Examiner, p. 14, 1954-05-14

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Stimson, Jr., Thomas E. (October 1955), "He Spies on Satellites", Popular Mechanics, p. 106

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Los Angeles Times, 1957-09-04

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, Jean Meeus, chapter 38: Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit

- ^ "This month Pluto's apparent magnitude is m=14.1. Could we see it with an 11" reflector?". Singapore Science Centre. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ "The astronomical magnitude scale". The ICQ Comet Information Website. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ Steven R. Chesley and Paul W. Chodas (March 17, 2004). "Recently Discovered Near-Earth Asteroid Makes Record-breaking Approach to Earth". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Grand Teton Meteor Video, Youtube

- ^ US19720810 (Daylight Earth grazer) Global Superbolic Network Archive, 2000, 'Size: 5 to 10 m'

See also

- List of hypothetical Solar System objects

- Lost asteroids, rediscovered celestial bodies

- Lagrange points

- Lilith (hypothetical moon), second earth moon in astrology

External links

- Earth’s Other Moon

- The Earth's Second Moon, 1846-present

- A detailed explanation of secondary moon theories

- Have astronomers discovered Earth's second moon?

- Near-Earth asteroid 3753 Cruithne --Earth's curious companion--

Further reading

- Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World on All Important Current Topics

Published by Public Opinion Co., 1898, Page 369. Book

- Willy Ley: "Watchers of the Skies", The Viking Press NY,1963,1966,1969

- Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan: "Comet", Michael Joseph Ltd, 1985, ISBN 0-7181-2631-9

- Tom van Flandern: "Dark Matter, Missing Planets & New Comets. Paradoxes resolved, origins illuminated", North Atlantic Books 1993, ISBN 1-55643-155-4

- Joseph Ashbrook: "The Many Moons of Dr Waltemath", Sky and Telescope, Vol 28, Oct 1964, p 218, also on page 97-99 of "The Astronomical Scrapbook" by Joseph Ashbrook, Sky Publ. Corp. 1984, ISBN 0-933346-24-7

- Delphine Jay: "The Lilith Ephemeris", American Federation of Astrologers 1983, ISBN 0-86690-255-4

- William R. Corliss: "Mysterious Universe: A handbook of astronomical anomalies", Sourcebook Project 1979, ISBN 0-915554-05-4, p 146-157 "Other moons of the Earth", p 500-526 "Enigmatic objects"

- Clyde Tombaugh: Discoverer of Planet Pluto, David H. Levy, Sky Publishing Corporation, March 2006

- Richard Baum & William Sheehan: "In Search of Planet Vulcan" Plenum Press, New York, 1997 ISBN 0-306-45567-6 , QB605.2.B38