Demographics of Gibraltar: Difference between revisions

m copyedit, MOS and or AWB general fixes using AWB (7069) |

→Spanish: rm WP:COATRACK |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

===Spanish=== |

===Spanish=== |

||

The majority of the [[Spanish Gibraltarians|Spanish population]], with few exceptions, left Gibraltar when the Dutch and English took the village in 1704. The few [[Spaniard]]s who remained in Gibraltar in August 1704 were augmented by others who arrived in the fleet with [[Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt]], possibly some two hundred in all, mostly [[Catalan people|Catalans]].<ref>[http://www.iteg.org/documentos/spaniards_in_gibraltar.pdf Spaniards in Gibraltar]</ref> |

|||

The majority of the [[Spanish Gibraltarians|Spanish population]], with few exceptions, left Gibraltar when the Dutch and English took the village in 1704. In spite of assurances that Spaniards who wished to remain would enjoy freedom of religion and full civil rights, and despite the efforts of British and Dutch senior officers to maintain order, lootings, desecrations and rapes were perpetrated by the ships' crew and marines.<ref>Andrews, Allen, [http://www.archive.org/stream/proudfortressthe011406mbp#page/n37/mode/2up ''Proud Fortress The Fighting Story Of Gibraltar''], p32-33: ''"The conquerors were out of control. (…)Into the raw hands of fighting seamen (…) alcohol and plunder and women passed wildly and indiscriminately. (…)The sack of Gibraltar was memorable through Andalusia for the peculiar fury of the invaders against the servants, houses and ornaments of the Catholic religion. (…) Every church in the city was desecrated save one.''</ref><ref>[[William Jackson (British Army officer)|Jackson, Sir William]], ''Rock of the Gibraltarians'', p100-101: ''"Although Article V promised freedom or religion and full civil rights to all Spaniards who wished to stay in [[House of Habsburg|Habsburg]] Gibraltar, few decided to run the risk of remaining in the town. [..] English atrocities at [[Cádiz]] and elsewhere and the behaviour of the English sailors in the first days after the surrender suggested that if they stayed they might not live to see that day. Hesse's and Rooke's senior officers did their utmost to impose discipline, but the inhabitants worst fears were confirmed: women were insulted and outraged; Roman Catholic churches and institutions were taken over as stores and for other military purposes [..] ; and the whole town suffered at the hands of the ship's crew and marines who came ashore."''</ref> The townspeople took reprisals, murdering Dutchmen and Englishmen.<ref>Andrews, Allen, [http://www.archive.org/stream/proudfortressthe011406mbp#page/n37/mode/2up ''Proud Fortress The Fighting Story Of Gibraltar''], p32-33: ''"The Spaniards could only retaliate with individual vengeance the knife in the back of a drink-hazed victor and the swift bundling of a body down a well."''</ref><ref>[[William Jackson (British Army officer)|Jackson, Sir William]], ''Rock of the Gibraltarians'', p100-101: ''"Many bloody reprisals were taken by inhabitants before they left, bodies of murdered Englishmen and Dutchmen being thrown down wells and cesspits."''</ref> When discipline was restored, most villagers decided to go in exile and, after some time, founded the nearby city of San Roque.<ref>Andrews, Allen, [http://www.archive.org/stream/proudfortressthe011406mbp/proudfortressthe011406mbp_djvu.txt ''Proud Fortress The Fighting Story Of Gibraltar''], p54: ''"(...) these 6,000 civilians resolved to exile themselves from the town.(…) But most of them settled in Spain round the hill of San Roque, within sight of the lost city. Their Sovereign, the Bourbon Philip V, whom the British soon recognised as lawful King of Spain, never ceased to regard them as the future burgesses of the fortress he daily mourned, and recognised the new municipality by Royal Patent as the Council, Tribunal, Officers and Gentlemen of the City of Gibraltar. To this day San Roque bears the arms and constitution of the Spanish City of Gibraltar in Exile.".''</ref><ref>[[William Jackson (British Army officer)|Jackson, Sir William]], ''Rock of the Gibraltarians'', p100-101: ''"Although Article V promised freedom or religion and full civil rights to all Spaniards who wished to stay in [[House of Habsburg|Habsburg]] Gibraltar, few decided to run the risk of remaining in the town. By the time discipline was fully restored, few of the inhabitants wished or dared to remain."''</ref> The few [[Spaniard]]s who remained in Gibraltar in August 1704 were augmented by others who arrived in the fleet with [[Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt]], possibly some two hundred in all, mostly [[Catalan people|Catalans]].<ref>[http://www.iteg.org/documentos/spaniards_in_gibraltar.pdf Spaniards in Gibraltar]</ref> |

|||

[[Minorca]]ns are a small and interesting group. Their migration to Gibraltar started since the beginning of the common British rule in 1713, thanks to the links between both British possessions during the 18th century, first looking for work in several trades, especially when Gibraltar needed to be rebuilt after the 1783 Grand Siege. Immigration continued even after Minorca was returned to Spain in 1802 by the [[Treaty of Amiens]]<ref>{{cite book |first=William |last=Jackson |year=1990 |title=The Rock of the Gibraltarians. A History of Gibraltar |publisher=Gibraltar Books | edition = second edition |location=Grendon, Northamptonshire, UK |isbn=0-948466-14-6 | page=225}}: {{cquote|The open frontier helped to increase the Spanish share, and naval links with Minorca produced the small Minorcan contingent.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2ip0C6odET4C | title=Gibraltar, identity and empire | author=Edward G. Archer | publisher=Routledge | year=2006 | isbn=9780415347969 | pages=42–43}}</ref>) |

[[Minorca]]ns are a small and interesting group. Their migration to Gibraltar started since the beginning of the common British rule in 1713, thanks to the links between both British possessions during the 18th century, first looking for work in several trades, especially when Gibraltar needed to be rebuilt after the 1783 Grand Siege. Immigration continued even after Minorca was returned to Spain in 1802 by the [[Treaty of Amiens]]<ref>{{cite book |first=William |last=Jackson |year=1990 |title=The Rock of the Gibraltarians. A History of Gibraltar |publisher=Gibraltar Books | edition = second edition |location=Grendon, Northamptonshire, UK |isbn=0-948466-14-6 | page=225}}: {{cquote|The open frontier helped to increase the Spanish share, and naval links with Minorca produced the small Minorcan contingent.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2ip0C6odET4C | title=Gibraltar, identity and empire | author=Edward G. Archer | publisher=Routledge | year=2006 | isbn=9780415347969 | pages=42–43}}</ref>) |

||

Revision as of 13:03, 7 December 2010

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Gibraltar |

|---|

|

| History |

| Cuisine |

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Gibraltar, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

Ethnic origins

One of the main features of Gibraltar’s population is the diversity of their ethnic origins. The demographics of Gibraltar reflects Gibraltarians' racial and cultural fusion of the many European and non-European immigrants who came to The Rock over three hundred years. They are the descendants of economic migrants that came to Gibraltar after the majority of the Spanish population left in 1704.

Spanish

The majority of the Spanish population, with few exceptions, left Gibraltar when the Dutch and English took the village in 1704. The few Spaniards who remained in Gibraltar in August 1704 were augmented by others who arrived in the fleet with Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt, possibly some two hundred in all, mostly Catalans.[1]

Minorcans are a small and interesting group. Their migration to Gibraltar started since the beginning of the common British rule in 1713, thanks to the links between both British possessions during the 18th century, first looking for work in several trades, especially when Gibraltar needed to be rebuilt after the 1783 Grand Siege. Immigration continued even after Minorca was returned to Spain in 1802 by the Treaty of Amiens[2][3])

Immigration from Spain and intermarriage with Spaniards from the surrounding Spanish towns was a constant feature of Gibraltar's history until the then Spanish dictator, General Francisco Franco, closed the border with Gibraltar in 1969, cutting off many Gibraltarians from their relatives on the Spanish side of the frontier.

Together, Gibraltarians of Spanish origin are one of the bigger groups (more than 24% according to last names, even more taking into account the fact that a larger share of Spanish women married native Gibraltarians).[4]

British

Britons have come and settled or gone since the first days of the conquest. One group of Britons have had temporary residence in Gibraltar (to work in the administration and the garrison). This group, who represented a larger proportion in the beginning of the British period, are nowadays only about 3% of the total population (around 1,000 individuals).

A larger group is formed by the Britons who moved to Gibraltar and settled down. Some of them, since the beginning, moved to Gibraltar to earn a living as traders and workers. Others moved to Gibraltar on a temporary assignment and then married with local women. Major construction projects, such as the dockyard in the late 1890s and early 20th century brought large quantities of workers from Great Britain.

The analysis of names in the electoral roll shows that 27% of Gibraltarians have British origin.[5]

Genoese and other Italians

Genoese came during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially from the poorer parts of Liguria, some of them annually following fishing shoals, as repairmen for the British navy, or as successful traders and merchants;[6] many others came during the Napoleonic period to avoid obligatory conscription to the French Army.[7] Genoese formed the larger group of the new population in the 18th century and middle 19th century. Other Italians came from islands like Sardinia and Sicily. Nowadays, people with Genoese/Italian last names represent about 20% of the population.

Portuguese

Portuguese were one of the earlier groups to move to Gibraltar, especially from the Algarve region in the south of Portugal. Most of them went to work as labourers and some as traders. Their number increased significantly during the 18th century, and again when many Spaniards left their jobs in Gibraltar after General Franco closed the border in 1969. About 10% of last names in Gibraltar have Portuguese origin.[8]

Moroccans

Moroccans have always had a significant presence in Gibraltar. However, the modern community has more recent origins. Moroccans began arriving in Gibraltar soon after the Spanish government imposed the first restrictions on Spanish workers in Gibraltar in 1964. By the end of 1968 there were at least 1,300 Moroccan workers resident in Gibraltar and this more than doubled following the final closure of the frontier with Spain in June 1969.[9]

Other groups

Other groups include:

- Maltese were in the same imperial route to the east as Gibraltar. They came when jobs were scarce at home and others to escape the law in Malta.[10]

- Jews, most of them of Sephardi origin, were able to re-establish their rites, forbidden in Catholic Spain, right after the British occupation in 1704. Also a significant number of Jews from London settled in Gibraltar, especially since the Great Siege.[11]

- Indians, most of them from Hyderabad, came as merchants after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1870; many others migrated as workers after the closure of the frontier with Spain in 1969 to replace Spanish ones.[12]

- French, many of whom came after the French Revolution in 1789, set up trade and commerce.[7]

- Austrians, Chinese, Japanese, Polish or Danish.

Demographic statistics

The following demographic statistics are from the CIA World Factbook, unless otherwise indicated.

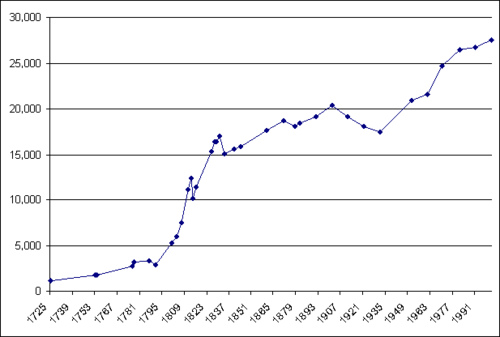

Population

28,895 (Jan 2008 est.)

Population age

0-14 years:

17.2% (male 2,460; female 2,343)

15-64 years:

66.3% (male 9,470; female 9,070)

65 years and over:

16.5% (male 2,090; female 2,534) (2007 est.)[13]

Sex ratio

At birth:

1.06 males/female

0-14 years:

1.05 males/female

15-64 years:

1.044 males/female

65 years and over:

0.825 males/female

total population:

1.005 males/female (2007 est.)[13]

Changing population

Population growth rate

The population growth rate for Gibraltar is 0.129% (2007 est.) (world growth rate at 2006 is 1.14%). Gibraltar also saw migration of 0 migrant(s)/1,000 population. (2007 est.)

The median age is:

total: 40.3 years

male: 39.8 years

female: 40.7 years (2008 est.)[13]

Life expectancy

total population:

79.93 years

male:

77.05 years

female:

82.96 years (2007 est.)[13]

Fertility

1.65 children born/woman (2007 est.)[13]

Births

10.69 births/1,000 population (2007 est.)[13]

Deaths

9.4 deaths/1,000 population (2007 est.)[13]

Infant mortality

total:

4.98 deaths/1,000 live births

male:

5.54 deaths/1,000 live births

female:

4.39 deaths/1,000 live births (2007 est.)[13]

Nationality

noun:

Gibraltarian(s)

adjective:

Gibraltar

The actual composition of the population by nationality from the 2001 census is as follows[14]:

| Nationality | Number | Prozentualer Anteil |

|---|---|---|

| Gibraltarian | 22,882 | 83.2 |

| Other British | 2,627 | 9.6 |

| Moroccan | 961 | 3.5 |

| Spanish | 326 | 1.2 |

| Other EU | 275 | 1.0 |

| Other | 424 | 1.5 |

Ethnic groups

Gibraltarian British (of mixed Genoese Italian, Maltese, Portuguese and Andalusian Spanish descent), other British, Moroccan and Indian.

Religions

Roman Catholic 78.09%, Church of England 6.98%, Other Christian 3.21%, Muslim 4.01%, Jewish 2.12%, Hindu 1.79%, other or unspecified 0.94%, none 2.86% (2001 census)[14]

Languages

English (used in schools and for official purposes), Spanish. Most Gibraltarians converse in Llanito, an Andalusian Spanish based vernacular. It consists of an eclectic mix of Andalusian Spanish and British English as well as languages such as Maltese, Portuguese, Italian of the Genoese variety and Haketia. Among more educated Gibraltarians, it also typically involves code-switching to English. Arabic is spoken by the Moroccan community, just like Hindi and Sindhi is spoken by the Indian community of Gibraltar. Maltese is still spoken by some families of Maltese descent.

Literacy

definition:

NA

total population:

above 80%

male:

NA%

female:

NA%

Educational attainment in Gibraltar

| Rank | Religion | Proportion (%) of pupils achieving 5 or more GCSE's (Grades A-C) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hindu | 79% |

| 2 | Jewish | 76% |

| 3 | All other religions | 68% |

| 4 | National average | 66% |

| 5 | Christian | 66% |

| 6 | None | 64% |

| 7 | Muslim | 44% |

| Rank | National origin | Percentage of people of working age with a degree |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indian | 71% |

| 2 | British | 26% |

| 3 | Other EU | 24% |

| 4 | All other national origins | 24% |

| 5 | National average | 23% |

| 6 | Gibraltarian | 23% |

| 7 | Spanish | 16% |

| 8 | Moroccan | 14% |

Crime rate

| Total crimes (per capita) by national origin | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moroccan | 9.4 per 100 people | |

| Gibraltarian | 6.3 per 100 people | |

| UK British | 6.3 per 100 people | |

| National average | 6.3 per 100 people | |

| Other EU | 5.8 per 100 people | |

| Other national origins | 5.4 per 100 people | |

| Indian | 1.6 per 100 people |

A total of 2,093 criminal offences were recorded in Gibraltar during 2005/2006. Indians had a significantly lower crime rate in 2005/2006 than all other national origins in Gibraltar at 1.69 crimes per 100 Indian people. The crimes per 100 population in Gibraltar now stands at 6.3. The crime rate for Gibraltarians and Moroccans has risen from 6.1 and 9.36 per 100 people in 2004/2005 to its current levels.

Notes

- ^ Spaniards in Gibraltar

- ^ Jackson, William (1990). The Rock of the Gibraltarians. A History of Gibraltar (second edition ed.). Grendon, Northamptonshire, UK: Gibraltar Books. p. 225. ISBN 0-948466-14-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help):The open frontier helped to increase the Spanish share, and naval links with Minorca produced the small Minorcan contingent.

- ^ Edward G. Archer (2006). Gibraltar, identity and empire. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780415347969.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 43. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 40. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 37. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ a b Levey, David: Language change and variation in Gibraltar, page 24. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 41. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ Sussex Migration Briefing - Steps to resolving the situation of Moroccans in Gibraltar

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 44. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 38. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ Archer, Edward G.: Gibraltar, identity and empire, page 45. Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Intute World Guide - Gibraltar.

- ^ a b Census of Gibraltar 2001.