1950s American automobile culture: Difference between revisions

Kelapstick (talk | contribs) →American suburbanization: image is more related to the subsection rather than the main section |

this is the kind of thing that Gerda was referring to on my talk page. If you don't like it I won't do any more. |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

[[File:ROUTE 66 sign.jpg|thumb|right|The Interstate system was a major upgrade to the still existing [[United States Numbered Highways|U.S. Highway System]].]] |

[[File:ROUTE 66 sign.jpg|thumb|right|The Interstate system was a major upgrade to the still existing [[United States Numbered Highways|U.S. Highway System]].]] |

||

{{main|Interstate Highway System}} |

{{main|Interstate Highway System}} |

||

The ''Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways'' (commonly called "the Interstate system") is a network of [[freeway]]s that forms a part of the [[National Highway System (United States)|National Highway System]] of the United States. Construction was authorized by the [[Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956]], and the original portion was completed 35 years later. The system has contributed in shaping the United States into a world economic superpower and a highly industrialized nation. |

The ''Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways'' (commonly called "the Interstate system") is a network of [[freeway]]s that forms a part of the [[National Highway System (United States)|National Highway System]] of the United States. Construction was authorized by the [[Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956]], and the original portion was completed 35 years later. The system has contributed in shaping the United States into a world economic superpower and a highly industrialized nation.{{r|Genie}} |

||

During |

During World War II Eisenhower gained an appreciation of the German [[German autobahns|Autobahn]] network as a necessary component of a national defense system while he was serving as [[Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force|Supreme Commander]] of the [[Allies of World War II|Allied forces]] in Europe during [[European Theatre of World War II|World War II]].<ref>{{cite journal| title= On the Road |first= Henry |last= Petroski |journal= American Scientist |volume= 94 |issue= 5 |year= 2006 |pages= 396–9 |issn= 0003-0996}}</ref> He recognized that the proposed system would also provide key ground transport routes for military supplies and troop deployments in case of an emergency or foreign invasion. |

||

The Interstate grew quickly over the next few decades, along with the automobile industry. People could now travel much greater distances in the same amount of time, and this new found mobility permeated ways of American life and culture as a large share of the population could travel long distances in their own vehicle at their leisure. The automobile and the Interstate became the American symbol of individuality and freedom.<ref name="hofstra">{{cite web | url=http://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch3en/conc3en/map_interstatesystem.html | title=The Geography of Transport Systems - The Interstate Highway System | publisher=Hofstra University | accessdate=October 14, 2012}}</ref> |

The Interstate grew quickly over the next few decades, along with the automobile industry. People could now travel much greater distances in the same amount of time, and this new found mobility permeated ways of American life and culture as a large share of the population could travel long distances in their own vehicle at their leisure. The automobile and the Interstate became the American symbol of individuality and freedom.<ref name="hofstra">{{cite web | url=http://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch3en/conc3en/map_interstatesystem.html | title=The Geography of Transport Systems - The Interstate Highway System | publisher=Hofstra University | accessdate=October 14, 2012}}</ref> |

||

| Line 316: | Line 316: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist| |

{{reflist|30em|refs= |

||

<ref name=Genie> |

|||

{{cite journal |last=Weingroff |first=Richard F. |month=September–October |year=2000 |title=The Genie in the Bottle: The Interstate System and Urban Problems, 1939–1957 |journal=Public Roads |location= Washington, DC |publisher= Federal Highway Administration |volume=64 |issue=2 |url=http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/00septoct/urban.cfm |accessdate=May 9, 2012 |issn=0033-3735}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

Revision as of 20:51, 2 December 2012

Automobiles brought about important changes in American culture in the 1950s. The decade ushered in the space age and the space race, which was reflected in the style of American automotive design. Large tail fins,[1] flowing designs that imitated rockets, and even radio antennas that imitated Sputnik were common. Some innovations such as push button automatic transmissions also came into production.[2] Many of the technological and cultural changes pioneered during the decade are still present today.

For the first time, the automobile became an integral part of the American culture, as reflected in popular music, the mainstream acceptance of the "hot rod" culture and the beginning of a new generation of service businesses centered around the customer and their auto. Henry Ford's goal of a generation before had come true, that any man with a good job could afford an automobile. [3]

After World War II, the American manufacturing economy switched from producing war related items to consumer goods, and by the end of the decade, fully 1 in 6 working Americans either worked directly or indirectly in the automotive industry. This helped make the United States the largest manufacturer of automobiles in the world for decades to come, and the decade left an indelible mark on the culture of the United States, in both positive and negative ways.

American suburbanization

The Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called "the Interstate system") is a network of freeways that forms a part of the National Highway System of the United States. Construction was authorized by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, and the original portion was completed 35 years later. The system has contributed in shaping the United States into a world economic superpower and a highly industrialized nation.[4]

During World War II Eisenhower gained an appreciation of the German Autobahn network as a necessary component of a national defense system while he was serving as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World War II.[5] He recognized that the proposed system would also provide key ground transport routes for military supplies and troop deployments in case of an emergency or foreign invasion.

The Interstate grew quickly over the next few decades, along with the automobile industry. People could now travel much greater distances in the same amount of time, and this new found mobility permeated ways of American life and culture as a large share of the population could travel long distances in their own vehicle at their leisure. The automobile and the Interstate became the American symbol of individuality and freedom.[6]

A new American identity

More people joined the middle-class in the 1950s, with more money to spend than ever, and the availability of consumer goods expanded along with the economy, including the ever improving automobile.[7] Americans were spending more time in their automobiles and viewing them as an extension of their own identity, helping fuel a boom in new automobile sales.[6] Everything that was related to the auto industry saw tremendous growth during the decade.[8]

For the first time, automobile buyers accepted that the automobile they drove indicated their social standing and level of affluence. It was a statement of their personality and an extension of themselves. The new designs and innovations appealed to a new generation tuned into fashion and glamour.[9]

Growth of the suburbs

The United States invested in infrastructure such as highways and bridges at the same time as the auto makers were making cars better suited for the higher speeds, allowing people to live outside the confines of major cities, and instead commute to and from work.[10] After World War II ended, land developers like William Levitt began to buy land just outside the city limits to produce to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses.[7] The promise of their own single-family home on their own land[11], together with a free college education and low interest loans given to returning soldiers to purchase homes under the G.I. Bill, drove demand for new homes to levels never seen before. Additionally, 4 million babies were born every year during the 1950s. By the end of the baby boom era in 1964, almost 77 million “baby boomers” had been born,[7] fueling the need for more housing in the suburbs, and automobiles to take them back and forth to the city centers for work and shopping.

By the end of the 1950s, fully 1/3 of Americans lived in the suburbs. Of the 12 largest cities in the US, 11 suffered population loss during the 1950s. The cost in lost tax revenues and city culture was obvious. Only Los Angeles, itself a center for the car culture, gained population, .[12] Economist Richard Porter summed it up rather succinctly when he said "The automobile made suburbia possible, and the suburbs made the automobile essential." [8]

Beginning of the end of the inner city

While not obvious at the time, this new found freedom and way of life in the suburbs had several negative consequences in the inner city. This was the beginning of white flight and urban sprawl, powered by the freedom granted by individual automobile ownership. Ironically, many local and national transportation laws would encourage suburbanization, which in time ended up damaging the cities economically.[13]

As more middle-class and affluent people fled the city to the relative quiet and open spaces of the suburbs, the central urban centers deteriorated and lost population.[14] At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of higher income earners, pressures from The New Deal forced them to offer pensions and other benefits, increasing the average cost of benefits per employee by a staggering 1,629%. This was in addition to hiring an average of 20% more employees to serve the ever shrinking cities. [14] More Americans were driving cars and fewer were using public transportation, and it wasn't practical to extend to the suburbs.[8] At the same time, the number of surface roads exploded to serve the ever increasing numbers of individually owned cars, further burdening city and country resources. During this time, the perception of using public transportation changed to a more negative one. In what is arguably the most extreme example, Detroit, which was the 5th largest city in the US in 1950 with 1,849,568 residents,[15] had shrunk to 706,585 people by 2010 [16], a reduction of 62%.

In some instances, the automotive industry and others were directly responsible for the decline of public transportation.[8]. The Great American streetcar scandal saw GM, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California, Phillips Petroleum, Mack Trucks and other companies purchase a number of streetcars and electric trains in the 1930s and 1940s, such that 90% of city trolleys had been dismantled by 1950. It was argued that this was a deliberate destruction of streetcars as part of a larger strategy to push the United States into automobile dependency.[17] In United States v. National City Lines, Inc., et al., many were found guilty of antitrust violations.[18] The story has been explored several times in print, film and other media, notably in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Taken for a Ride and The End of Suburbia.

Changes in the industry

As the automobile industry was maturing, a number of radical changes took place. No longer a coach industry, mass production and the ability to benefit from economies of scale led to a number of changes in the business end of the industry. One of the most significant changes was the successful campaign of marketing the V8 engine to a public that was ever ready for more powerful and larger automobiles. Another was consolidation of the industry. While the decade started with a number of independent auto manufacturers, it ended with virtually none, as the independents were consolidated or went out of business altogether.

The Big Three get bigger

While 125 automobile companies had sprang up in Detroit at the beginning of the 20th century, Ford quickly rose to the top and by the close of the 1950s, the industry was dominated by what would soon be called the "Big Three", who employed (directly or indirectly) one out of six working Americans. [19]

In American automobile parlance, the Big Three refers to General Motors (GM), Ford and Chrysler. Each of these companies has either bought out other companies or produced cars under a number of other brand names. As an example, General Motors produced Chevrolet, Buick, Pontiac (now defunct), Cadillac and Oldsmobile (now defunct), as well as GM light, medium and heavy duty trucks. Ford sold cars under the Lincoln and Mercury names, as well as the Ford line. Chrysler had the Plymouth(now defunct), Imperial (automobile) (1955-1975), Desoto (now defunct) and Dodge, in addition to Chrysler branded vehicles. Since the 1950, a number of other mergers, buyouts and closures of auto lines have taken place with all three manufacturers.

Each of these individual divisions was a standalone auto manufacturer at one time, and the 1950s saw an increase in the power of the three largest manufacturers of the time. While many other brands saw a decline in sales or simply went out of business, the Big Three grew larger, as did the power and influence of the associated labor unions.[19] By the mid 1950s, 35% of all nonagricultural workers in America belonged to a union. Memberships grew over the coming years, but the economy grew even faster, and the actual percentage of total workers declined after the 1950s[20], but labor unions had permanently established themselves in the American economy.

American Motors is founded

In 1954, the smaller American Motors was formed when Hudson merged with Nash-Kelvinator Corporation, in what was at the time the largest corporate merger in U.S. history, worth nearly $200 million.[21] Other mergers with smaller independent manufacturers followed; yet American Motors (AMC) was never large enough to eclipse any of the Big Three.

The Hudson Hornet of the 1950s enjoyed some success, particularly in NASCAR.[22]The 1953 Hornet served as the basis for the character "Doc" in Pixar's 2006 blockbuster movie Cars. Doc was based on the real life Fabulous Hudson Hornet, which was actually a series of different race cars driven by Marshall Teague and Herb Thomas.

The Rambler was the company's most successful model of the time. It was based on previous models by Nash,[23] and eventually became a completely new brand in 1957, with production continuing under this name until 1969.

After American Motors was formed from most of the remaining independent automakers, no other independent has since had an impact in the American automotive sales market, making the 1950s the end of the era of independent makers.

Willys enjoyed tremendous success building jeeps for the U.S. military during World War II[24] but suffered stagnant sales after this time. It was purchased by Henry J. Kaiser who had already formed Kaiser-Frazer, to become the Kaiser-Willys Sales Corporation. Plummeting sales caused the Willys brand name to be abandoned by Kaiser by 1955, which had begun using the name Jeep for the new Kaiser-Jeep built vehicles; the company was bought out by AMC in 1970.[25]

Notable failures

In 1956, Ford tried to revive the Continental brand as a standalone line of ultra luxury automobiles, but abandoned the attempt after the 1957 model year after building around 3000 Mark II cars. The failure was due in part to the price tag, $9695, which was an extraordinary amount of money for the time.[26] The Continental thereafter became a successful car model under Ford's Lincoln brand.

The Edsel made its debut as a separate car division of Ford on September 4, 1957, for the 1958 model year. It ended up being a marketing blunder that not only set back Ford almost $250 million, a staggering amount at the time, but the failure turned the word "Edsel" into a neologism that still exists today. Named after Henry Ford's son Edsel Ford, the car sold very few units, and production for the final 1960 model year had ceased by November 1959.[27]

Kaiser[28], Frazer[29] and the economy/compact Henry J[30] product lines all ceased production before the end of the 1955 model year run partly due to the failure to produce and market a viable V8 engine in a marketplace increasing focus on the clout (and horsepower) associated with a V8 power plant. In particular, the Henry J (named after Henry J Kaiser sold an initially strong 82,000 units with its 68hp, inline-four power plant and optional 80hp inline-six, but starting at $1363, the consumer could buy a full sized Chevrolet auto with an inline-6 for only $200 more than the Henry J inline-4, making it economically unappealing and all three lines underpowered when compared to the offerings of the Big Three.

DeSoto[31] died a slow death in the 1950s due to circumstances beyond the control of Chrysler. As Chrysler had moved their primary product line into the main stream price range when they came out with the upper priced Imperial line, putting it in direct competition with their own DeSoto line. By 1958, sales were under 50,000 units per year and the in its final year, 1961, Desoto was no longer a line of cars but marked simply as the DeSoto, and offered in a two door hardtop as well as a four door hardtop model only.[32]

Packard began the 1950s on a difficult note, as sales dropped from 116,248 in 1949 to an underwhelming 42,627 in 1950.[33] While their higher end products enjoyed advanced features like automatic transmissions as standard equipment, their overall body design was considered dated. They merged with Studebaker in 1954 to form Studebaker-Packard Corporation, but they were forced to cease production of Packards in late 1958 after failing to keep up with the advances and sales of the Big Three.

Studebaker had enjoyed earlier success and was the first independent automaker to produce a V8 engine,[34] a 232.6 cubic inch, 120hp unit, which was also the first V8 in the low price field. After the 1954 merger failed to fix the financial woes that had plagued Studebaker for years, the company renamed itself the Studebaker Corporation in 1962 and was defunct by 1967.

Industry sales

During the 1950s, sales of new automobiles increased significantly. This table shows the number of sales reported for each American automotive manufacturer.

| Company | Units sold |

|---|---|

| Chevrolet | 13,419,048 |

| Ford | 12,282,492 |

| Plymouth | 5,653,874* |

| Buick | 4,858,961 |

| Oldsmobile | 3,745,648 |

| Pontiac | 3,706,959 |

| Mercury | 2,588,472 |

| Dodge | 2,413,239* |

| Studebaker (U.S.) | 1,374,967 |

| Packard ('50-'58) | 1,300,835 |

| Chrysler | 1,244,843* |

| Cadillac | 1,217,032 |

| Nash ('50-'57) | 974,031* |

| DeSoto | 972,704* |

| Rambler ('57-'59) | 641,068* |

| Hudson ('50-'57) | 525,683* |

| Lincoln | 317,371 |

| Kaiser ('50-'55) | 224,293 |

| Henry J ('51-'54) | 130,322 |

| Edsel ('58-'59) | 108,001 |

| Imperial ('55-'59) | 93,111 |

| Willys ('52-'55) | 91,841 |

| Continental ('56-'58) | 15,550* |

| Frazer ('50-'51) | 13,914* |

| Total (estimate) | 57,914,259* |

- These numbers are based on some estimates.[35] Total covers only these models, not import or other models sold during this time.

"Hot rod" becomes mainstream

The increase of popularity of hot rodding cars is in part evident by the creation of special interest magazines that cater to this culture. Hot Rod is the oldest magazine devoted to hot rodding having been published since 1948. Robert E. Petersen founded the magazine and his Petersen Publishing Company was the original publisher. Hot Rod has licensed affiliation with Universal Technical Institute. The first editor of Hot Rod was the legendary Wally Parks.

The relative abundance and inexpensive nature of Ford Model T and other cars from the 1920s to 1940s helped fuel the hot rod culture that developed, which was focused on getting the most linear speed out of these older automobiles. While the origin of the term "hot rod" is unclear, the culture blossomed in the post-war culture of the 1950s. [36]

As the decade progressed, hot rodding became a popular hobby for a growing number of teenagers as the sport literally came to Main Street.[37]

Birth of the drag strip

Drag racing has been around as long as there have been cars, but it was until the 1950s that it begun to become mainstream, which started with Santa Ana Drags, the first drag strip in the United States.[38] The strip was founded by C.J. "Pappy" Hart, Creighton Hunter and Frank Stillwell at the Orange County Airport auxiliary runway in southern California [39] and was operational from 1950 until June 21, 1959[39]

Hot Rod editor Wally Parks created the National Hot Rod Association in 1951, which is still the largest governing body in the popular sport.[38] As of October 2012, there are at least 139 professional drag strip operational in the United States.[40] One of the most powerful racing fuels ever developed is nitromethane, which traces its roots as a racing fuel to the 1950s, and is still the primary component used in Top Fuel drag racing. [41]

NASCAR

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) was incorporated Feb. 21, 1948 by Bill France, Sr. and built its roots in the 1950s.[42] Two years later in 1950 the first asphalt "superspeedway", Darlington Speedway was opened in South Carolina, and the sport saw dramatic growth during the 1950s.[42] Because of the tremendous success of Darlington, construction of a 2.5-mile, high-banked superspeedway began near Daytona Beach, which is still in use.[42]

The Cup Series was started in 1949, with Jim Roper winning the first series.[42] By 2008, the most prestigious race in the series, the Daytona 500 had attracted over 17 million television viewers. [43] Dynasties was born in the 1950s with racers like Lee Petty (father of Richard Petty, grandfather of Kyle Petty) and Buck Baker (father of Buddy Baker).

NASCAR, and stock car racing in general, has its roots in bootlegging during Prohibition[44] Bootleggers were common in the sport in the 1950s, such as Junior Johnson, who is just as known both for his racing success as his 1955 arrest for operating his father's moonshine still. [45] He ended up spending a year in an Ohio prison, [46] but soon returned to the sport before retired as a driver in 1966.[44]

Today, NASCAR is the second most popular spectator sports in the United States behind the National Football League.[47]

"Drive-in, drive up, drive through"

Faster food

As more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into being to allow them to enjoy their products and services without having to leave their car. This included the drive-in restaurant and the drive-in movie. These were later romanticized in popular culture with the movie American Graffiti and the television show Happy Days. Still today, the Sonic Drive-In restaurant chain provides primarily drive-in service by carhop in 3,561 restaurants in 43 U.S. states, serving approximately 3 million customers per day.[48][49] Known for its use of carhops on roller skates, the company annually hosts a competition to determine the top skating carhop in its system.[50]

A number of other successful "drive up" businesses have their roots in the 1950s, including McDonalds, which had no dine-in facilities, requiring customers to park and walk up to the window, taking their order "to go". Businessman Ray Kroc joined the company as a franchise agent in 1955. He subsequently purchased the chain from the McDonald brothers and oversaw its worldwide growth.[51] Both of these restaurant models initially relied on the new and ubiquitous ownership of automobiles, and the willingness of patrons to eat in their automobiles, and today drive-through service accounts for 65% of their profits.[52]

Drive-in movies

The drive-in theater is a form of cinema structure consisting of a large outdoor movie screen, a projection booth, a concession stand and a large parking area for automobiles, where patrons view the movie from the comfort of their car and listened via a speak placed at each parking spot. Although drive-in movies first appeared in 1933[53], it wasn't until well after the post-war era that they became popular, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s. While drive-in theaters are more rare today and no longer unique to America, they are still associated as part of the 1950s American car culture.[53]

Bigger is better

The appetite for larger cars, larger engines with more horsepower, more chrome and even larger tailfins were evident as the decade progressed. While there were a number of compact cars produced in the 1950s, both domestic like Crosley and imports such as the original Toyopet in 1958, which was soon renamed the Toyota Crown [54][55]. Volkswagen had began importing the Beetle in 1949 but sales were slow for years and wouldn't see a surge in popularity until the late 1960s.[56][57]

Aftermarket

The 1950s jump started and industry of aftermarket add-ons for cars that continues today. American Racing, is the oldest aftermarket wheel company and started in 1956 and still builds "mag wheels" (alloy wheels) for almost every car made.[58] Holley introduced the first modular four-barrel carburetor, which Ford offered in the 1957 Ford Thunderbird[59], and versions are still used by performance enthusiasts. Owners were no longer bound by the original equipment that manufacturers provided, helping not only create the hot rod culture[60], but the foundation for cosmetic modifications as well. The creation and rapid expansion of the aftermarket made it possible for enthusiasts to make their automobiles as unique as they were.

Automotive innovations

Many innovations made it safer to drive at higher speeds, or required less effort. New safety equipment, lower relative prices and the growing number of suburbs (fed by the new highway system) driving automobiles became more common, as did driving greater distances, which was getting more comfortable and safer. This helped feed the desire to replace cars soon, as each new model had more technology, more creature comforts and safety features than the year before during the 1950s.

The first automatic transmissions were developed by General Motors during the 1930s but it wasn't until 1950 that Chevrolet offered them on inexpensive cars[61]. By 1952, 2 million cars per year were sold with automatics[61], representing half the total units sold.[62] By the end of the decade, automatic transmissions dominated new car sales.

Before the 1950s, most automobiles had been built using a kingpin based front suspension. This limited the degree of free movement, and ultimately the smoothness of the ride, particularly at higher speeds. While not quite as durable as a kingpin suspension, the newer suspensions made the cars safer, more controllable and comfortable at the new highway speeds.[63]

Spoke wheels were used until the 1950s, which were lighter but were not as safe at highway speeds.[64] They gave way to solid metal wheels, which added to the safety and durability of the automobile, and allowing larger, smoother riding tires.

Unibody construction didn't come into popular use until the 1950s.[64] Unlike the older chassis design, unibody construction allowed greater distribution of the load over the entire frame of the car, making them more rigid, easy to handle, thus safer.

American car manufacturers Nash was the first automaker to offer optional seatbelts in 1949[65]) and Ford soon followed suit, but it was Swedish automaker Saab who first made seat belts as standard in 1958,[66] and the US builders followed soonafter.[67] The car was progressively becoming safer as the decade progressed.

The 1953 Chrysler Imperial was the first production car in twelve years to actually have automobile air conditioning, following tentative experiments by Packard in 1940 and Cadillac in 1941.[68] The Pontiac Star Chief offered the first modern "under hood" design in 1954. [69] and by the end of the decade, most lower priced autos offered air conditioning as an option.

Chrysler Corporation introduced the first commercially available passenger car power steering system on the 1951 Chrysler Imperial, marketed the name Hydraguide.[70] General Motors introduced the 1952 Cadillac with a power steering system based on research done for the company almost twenty years earlier.[71]

Power brakes had been invented in 1903, but they didn't become commonplace until the 1950s.[72] Self-adjusting brakes initially were offered on the 1957 Mercury and 1958 Edsel, and other manufacturers soon followed suit.[73]

The 1950s saw the changeover from using generators to alternators in the car's charging system, and by 1960, most vehicles were using the superior alternator system, allowing the great use of electrical devices such as power windows and seats in the car.[74], including the first car heated seats, credited to Cadillac in 1966.[75]

Cruise control has existed in automobiles since 1910, and usually consisted of a centrifugal governor that controlled engine speed rather than vehicle speed. This systems was based on an invention from 1788 by James Watt and Matthew Boulton[76], which used a similar method for use in locomotives. These were most notably used by Peerless.[77] The modern cruise control system, which controls actual vehicle speed, traces its roots to blind inventor Ralph Teetor, who invented the system[78] in 1945. It was until 1958 that the new cruise control, then dubbed "Auto-piolt"[79] was offered on Imperial and select Chrysler vehicles. General motors followed suit the next year by offering a similar system in their Cadillac lineup.[80] By 1960, every major automobile manufacturers offered cruise control as an option. [78]

Near misses

Several technologies were invented or at least became workable in the 1950s, yet took years or decades to become common place. In some cases, the technology simply wasn't ready, and in other cases, the buying public would accept or more commonly, wouldn't pay the extra cost. This includes disk brakes, first offered on the Chrysler Imperial and Town and Country models, but they were not as effective and were offered as a $400 option, forcing Chrysler to abandon the option and return to drum brakes after 1954.

John Hetrick invented the first airbag in 1953 (U.S. Patent #2,649,311), what he called at the time a "safety cushion assembly for automotive vehicles."[81] Others followed suit, even though it wasn't until over 30 years later that they become common. Anti-skid breaks (a form of anti-lock brakes) was invented by Road Research Laboratories in Great Britain in 1958, but wouldn't see widespread use in the U.S. for decades.[73][82]

Radial tires, first invented in 1915 by Arthur W. Savage[83] but it wasn't until 1948 that Michelin brought the first steel belted radial to market. Due to the harsher ride and higher expense, it would be three decades in 1978 before they overcame bias-ply tires as OEM use in the US, as car manufacturers began designing auto suspensions specifically designed for the tire design.[84] This left autos of the 1950s dominated by the use of bias-ply tires.

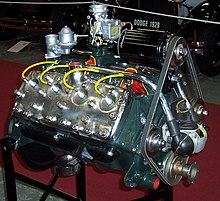

V8 engine

Ford had introduce the flathead V8 engine 1932, and it quickly had gained popularity[85], but the 1950s saw the most dramatic changes in the V8 in both reliability and power. In particular was the Chevrolet small block 265 cubic inch engine that was released in the 1955 model year, which itself became the basis for the subculture, and is the same foundation for the V8 engines still in use by General Motors today.[86] The original 265 cubic inch engine with a two-barrel carburetor produced 162 horse power[87], while the four-barrel version in the 1955 Corvette produced 195 hp[88], an amazing amount of power at the time. By 1957, the engine had been increased to 283 cubic inches.[89], including one fuel injected version that produce 283 hp, the first engine to have a ratio of 1:1 horse power versus cubic inches.[90]

Ford introduced the Ford Y-block engine mid-decade and the similar but larger Lincoln Y-block V8 engine for their luxury car lines in 1954.[91] The first Ford Y-block displaced 239 cubic inches and was rated at 130 horsepower, a significant step up from the 105hp rating of the flathead.[91] Like the GM motor, it used an overhead valve design rather than the inblock valve design inherent to all flathead engines.[91]

Chrysler created their V-8 Firepower engine for the 1951 model year, using hemispherical combustion chambers. It displaced 331.1 cid and produced an impressive 180 hp at 4000 rpm[92] While the name "Firepower" is no longer used, the name "Hemi" is still synonymous with Chrysler as a trademarked name for its engines, although they no longer use hemispherical combustion. By 1959, Chrysler had a 375hp, 413cid engine in their Chrysler 300, triple the average horsepower from a decade before[93], setting a trend that would continue through the next decade.

The 1950s gave birth to the horsepower war and started the muscle car era that continued until the smog regulations of the early 1970s forced manufacturers to scale back the emissions, thus the horsepower of their engines. The transition from flathead engines to a overhead valve design allowed greater RPMs, which in turn led to higher horsepower ratings, although at the expense of the new engines being heavier and more complicated in design. Other powerful engines had come before, including the Straight 8 (most notably in the 1921 Duesenberg straight-8)[94] and several companies developed V12 engines, but none had the societal and marketing impact of the V8. Many maker adorned their automobiles with "V8" emblems to advertise the power plant on their "fully loaded" automobiles, and the V8 engine soon became the engine of choice for power hungry consumers, turning the V8 engine itelf into an American icon.

Songs celebrating the automobile

As the automobile became more and more an extension of the individual, it was natural for this to be reflected in popular culture. America's love affair with the automobile was most evident in the music of the era.

- Rocket 88 was first recorded in 1951 and originally credited to Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats, although later discovered to be Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm. It is often credited as the first Rock and Roll song ever produced. [95] and has been covered by other artists.

- Hot Rod Lincoln was first recorded in 1955 by Charlie Ryan and The Livingston Brothers, and has since been recorded by Roger Miller, with the 1960 Johnny Bond version charting at #26 on Billboard Hot 100. Even comedian Jim Varney produced a version with Ricky Skaggs playing guitar. The song is still a popular live song for artists such as Asleep at the Wheel and Junior Brown.

- Teen Angel was released in 1959 and initially met with resistance by radio station due to the dark message about a young girl who dies in an automobile/train accident.

Other songs, such as Brand New Cadillac, Sonny Burgess's Thunderbird, Bo Diddley's Cadillac and others celebrate the automobile as part of the American culture.

Lingering influences

The 2000s have seen a resurgence of retro styling in new automotive design, sometimes blending ideas from different eras. Cars like the Chrysler PT Cruiser started a trend of retro yet practical vehicles. Soon after, the Chevrolet HHR was created by the same designer[96] and is an obvious example of retro design, with obvious similarities to the Chevrolet Suburban of the 1950s. The Suburban itself has been in production since 1935 (excepting 1943-1945, when war time rationing forced all automakers to stop domestic production) making it one of the longest lived model names in the industry.[97]

While cars from the 1960s such as the Ford Mustang and Dodge Challenger are more likely to be recreated in retro fashion, the larger era still holds a bit or romance for American buyers today. Additionally, a number of models first introduced in the 1950s are still in production after several generational upgrades. In other cases, names first used in or around the 1950s have been reintroduced for new models that do not share a common developmental line, and are used solely for marketing purposes.

Chevrolet Corvette

First introduced in 1953, the Corvette is America's supercar[98] and has been in continuous production ever since, enjoying a loyal following.[99]

Chevrolet Impala

Introduced in 1958, the Impala enjoyed tremendous success throughout the late 1950s until originally canceled in 1985. [100] Production resumed in 1994[101], and apart from 1999, has continued since.

Ford Thunderbird

The Thunderbird started as a sports car in 1955[102], but by the 1970s had grown to a much larger luxury coupe. It was produced from 1955 through 1997[102] and again from 2002 to 2005.[102]

Ford F-Series

The moniker F-Series was first used in 1948 and has been used continuously since. It includes the F-150, which has been the best selling pickup for over three decades. [103]

Chrysler 300

This model was first introduced in 1955 as the C-300, powered by the 331 hemi.[104] Only 1,725 were built and sold for $4,109, a steep price at the time.[105] The marque has undergone a large number of changes over the years, including the Chrysler 300 letter series and Chrysler 300 non-letter series of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, before being reintroduced in 2004 under the Chrysler 300 name. The new Chrysler 200 model was introduced in 2011 which was effectively a renaming of the Sebring, playing on the marketing power and history of the 300 model name.[106]

Chrysler Town and Country

The original Town and Country was a station wagon built from 1941 – 1988. The original 1941 model was a luxury woody wagon and sold less than 1000 units, but by 1951 had lost its wood panels. By 1959, consumers could choose from 22 different interior material and the wagon offered new innovations such as cruise control and air conditioning.[107] Chrysler re-purposed the name back in 1984 as the best seller Chrysler Town & Country minivan.[108]

See also

- Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952 - Authorized $25 million in highway subsidies to states in a 50/50 sharing program.[109]

- Tri Five - The 1955-57 Chevrolet offerings.

- Aerocar

References

- ^ John Gunnell (2004). p.15

- ^ Jon G. Robinson (2006). p.6

- ^ H. Eugene Weiss (1 September 2003). Chrysler, Ford, Durant, and Sloan: Founding Giants of the American Automotive Industry. McFarland. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-7864-1611-0. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^

Weingroff, Richard F. (2000). "The Genie in the Bottle: The Interstate System and Urban Problems, 1939–1957". Public Roads. 64 (2). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. ISSN 0033-3735. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Petroski, Henry (2006). "On the Road". American Scientist. 94 (5): 396–9. ISSN 0003-0996.

- ^ a b "The Geography of Transport Systems - The Interstate Highway System". Hofstra University. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c "The 1950s". The History Channel. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Peter Dauvergne (31 October 2008). The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment. MIT Press. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-262-04246-8. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "America on the Move - Making the Sale". Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Hearst Magazines (February 1958). Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 144–. ISSN 00324558 Parameter error in {{issn}}: Invalid ISSN.. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Land Development Calculations 2001 Walter Martin Hosack. "single-family detached housing" = "suburb houses" p133

- ^ "Society in The 1950s". Scmoop. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "America on the Move - The Sprawling Metropolis". Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Brian Greenberg; Linda S. Watts; Richard A. Greenwald (23 October 2008). Social History of the United States. ABC-CLIO. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-59884-128-2. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "US Census - Largest Cities in 1950". US Dept. of Census. June 15, 1998. Retrieved December 01, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places Over 50,000, Ranked by July 1, 2011 Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011" (CSV). 2011 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. June 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Snell, Bradford (26 February 1974). "Statement of Bradford C. Snell Before the United Sates Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly" (PDF). Hearings on the Ground Transportation Industries in Connection with S1167. S.C.R.T.D. Library. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Lindley, Walter (January 3, 1951). "United States v. National City Lines, Inc., et al". United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- ^ a b Sugrue, Thomas J. "Motor City: The Story of Detroit". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Eric Arnesen (16 November 2006). Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History. CRC Press. pp. 1248–. ISBN 978-0-415-96826-3. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Quella, Chad. "The Spirit Is Still Alive: American Motors Corporation 1954-1987". AllPar. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ Nerad, Jack. "Hudson Hornet (and racing) — as seen in Pixar's movie, Cars". Driving Today. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.302

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.314

- ^ Jim Allen (15 November 2004). Jeep. MotorBooks International. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-7603-1979-6. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.94

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.134

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.192

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.166

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.168

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.198

- ^ Bowman, Richard. "The 1955-1961 DeSoto cars: End of the line". Allpar. Retrieved December 01, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.266

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.306

- ^ Consumer Guide (2007) p.320

- ^ Robert Genat; Don Cox; Wally Parks (1 April 2003). The Birth of Hot Rodding: The Story of the Dry Lakes Era. MotorBooks International. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-7603-1303-9. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Freiburger, David (June 2012). "Real Rods of the '50s - The Genuine Article Read more: http://www.hotrod.com/thehistoryof/retrospective/hrdp_1206_real_hot_rods_of_the_1950s/#ixzz29NsVeY00". Hot Rod Magazine. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b "NHRA history: Drag racing's fast start". National Hot Rod Association. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Prieto, Don (1999). "Santa Ana Drags... The End of an Era". wediditforlove.com. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Dragstrips Drag Racing Tracks Directory". Drag Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Nitromethane: Top-Fuel Drag Racing's Soup of Choice". Drag Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "History of NASCAR - Bill France Sr.'s vision now staple of sports landscape". NASCAR.com. March 8, 2010. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "2009 NASCAR Sprint Cup TV Ratings". Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Houston, Rick (November 01, 2012). "The Moonshine mystique - NASCAR's earliest days forever connected to bootlegging". NASCAR. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Wolfe, Tom (May 23, 2010). "The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!". Esquire. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Menzer, Joe (2001). The Wildest Ride: A History of NASCAR. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 59. ISBN 9780743205078.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (June 17, 2012). "All Of Nascar Gets Boost With A Dale Earnhardt Win". Forbes. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Business". Form 10-K Annual Report. Sonic Drive-In. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Phelps, Jonathan (2009-09-09). "Sonic Barrier Broken — 1950s-Style Drive-In Food Chain, Long Awaited by Its Fans, Arrives in Mass. with a Boom, and Traffic Jams Follow". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Conor Shine (September 13, 2011). "Sonic carhops skating for the big prize". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "McDonald's History". Aboutmcdonalds.com. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ Vanderbilt, Tom (December 11, 2009). "Has the American romance with the drive-through gone sour?". Slate. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Don Sanders; Dr Susan Sanders (1 August 2003). The American Drive-In Movie Theater. MBI Publishing Company. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-7603-1707-5. Retrieved 1 December 2012. Cite error: The named reference "SandersSanders2003" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "1958 Toyopet". Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Toyopet" (PDF). Toyota. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Volkswagen History". HistoMobile.com. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Sales Brochure - Volkswagen 1949 Beetle". PaintR.

- ^ "American Racing takes on the Hot Rod Power Tour". American Racing. May 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Holley History". Holley. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ David N. Lucsko (7 October 2008). The Business of Speed: The Hot Rod Industry in America, 1915–1990. JHU Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-8018-8990-5. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ a b Martin H. Levinson (May 2011). Brooklyn Boomer: Growing Up in the Fifties. iUniverse. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-1-4620-1712-6. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Robert Genat (15 November 2004). The American Car Dealership. MotorBooks International. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-7603-1934-5. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Matt Joseph (14 October 2005). Collector Car Restoration Bible: Practical Techniques for Professional Results. Krause Publications. pp. 254–. ISBN 978-0-87349-925-5. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b Giancarlo Genta; L. Morello (13 February 2009). The Automotive Chassis: Volume 1: Components Design. Springer. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-1-4020-8674-8. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ John Gunnell (2004). p.162

- ^ "The man who saved a million lives: Nils Bohlin - inventor of the seat belt - Features, Gadgets & Tech". The Independent. 2009-08-19. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ "Trollhattan Saab — Saab 9-1, 9-3, 9-4x, 9-5, 9-7x News". Trollhattansaab.net. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ^ Langworth, Richard M. (1994). Chrysler and Imperial: The Postwar Years. Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-87938-034-9.

- ^ John Gunnell (2004). p.222

- ^ Lamm, Michael (1999). "75 years of Chryslers". Popular Mechanics. 176 (3): 75. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Watson, Bill (22 March 2006). "History of Power Steering". Imperial Automobile Club Archives. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Hitting the Brakes: A History of Automotive Brakes". Second Chance Garage. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "Automobile History - Brakes". Motor Era. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Watson, Bill and Zatz, David and Redgap, Curtis. "A brief history of Chrysler and the alternator". Allpar. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "1960-1969 Cadillac". HowStuffWorks.com - Consumer Guide. Retrieved December 01, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Brown, Richard (1991). Society and Economy in Modern Britain 1700-1850. London: Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-203-40252-8.

- ^ "Speed Control Systems" (PDF). Ain Sham University. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b William S Hammack (6 September 2011). How Engineers Create the World: Thee Public Radio Commentaries of Bill Hammack. Bill Hammack. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-9839661-0-4. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ "1958 Chrysler / Imperial brochure". http://www.oldcarbrochures.com. 1958. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ "GM Heritage Center". Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bellis, Mary. "The History of Airbags". About.com. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ McCormick, Lisa Wade (September 25, 2006). "A Short History of the Airbag". Consumer Affairs. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ U.S. patent 1,203,910, May 21, 1915, Vehicle Tire, Inventor Arthur W. Savage

- ^ "Radial tire spawned industry revolution" (PDF). itec-tireshow.com. 1988. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "The Ford V8 "Flathead"". Ford Motor Company. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mike Meuller (2005). p.10

- ^ "Chevy Corvette 1955 Technical Specifications". Unique Cars and Parts.

- ^ Mike Meuller (2005). p.35

- ^ Mike Meuller (2005). p.19

- ^ Mike Meuller (2005). p.73

- ^ a b c McMasters, Tim. "About The Y-Block Ford". Yblockguy.com. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Jon G. Robinson (2006). p.15

- ^ Jim Glastonbury (2004). p.18

- ^ Melissen,Wouter (December 17, 2007). "Duesenberg Model A Phaeton". Ultimate Car Page.com. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Bill Jahl, Biography of Jackie Brenston, Allmusic,com

- ^ Neil, Dan. "Bob Lutz's hits and misses at GM". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Chevrolet Suburban History". Edmonds. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Michael L. Berger (2001). The Automobile in American History and Culture: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-313-24558-9. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Randy Leffingwell (4 June 2012). Corvette Sixty Years. MotorBooks International. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-7603-4231-2. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "History of the Chevrolet Impala 1958-2011". Chevy Impala Forum. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "1994 Impala SS". Motor Trend. 1994. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c John Gunnell (1 January 2004). Standard Catalog of Thunderbird: 1955-2004. Krause Publications. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-87349-756-5. Retrieved 1 December 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Gunnell2004" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ford Motor Company (2007-05-25). "Ford's Best Selling Pickups Add More Features For 2008". Truck Trend. Auto News.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Chrysler 300". CHRYSLER 300 CLUB INTERNATIONAL, INC. September 18, 2012. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Chrysler 300 History". Edmunds. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Loh, Edward (December 14, 2010). "First Test: 2011 Chrysler 200 Limited - Sebring is Dead, Long Live the 200". Motor Trend. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mermel, Harold. "Woodie Years". Allpar. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Chrysler Town and Country History". Edmunds. Retrieved December 02, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ John Gunnell (2004). p.104

Bibliography

- Consumer Guide (2007). American Cars of the 1950s, published by Publications International, Ltd. Template:ISBN-13

- Jon G. Robinson (2006). Standard Catalog of 1950s Chrysler, published by Krause Publications, Template:ISBN-13

- Mike Meuller (2005). Chevy's Small Block V-8: Five Decades of Power and Performance, published by National Street Machine Club Template:ISBN-13

- Jim Gastonbury (2004). The Ultimate Guide to Muscle Cars, published by Chartwell Books, Inc. Template:ISBN-13

- John Gunnell (2004). Standard Guide To 1950s American Cars, published by Krause Publications, Template:ISBN-13

- Rusty McClure (2006). Crosley - Two Brothers and a Business Empire That Transformed the Nation, published by Clerisy Press, Template:ISBN-13

- Robert Genat and David Newhardt (2008). American Cars of the 1950s, published by Motorbooks, MBI Publishing Company, LLC, Template:ISBN-13

- Dennis Adler (1996). Fifties Flashback, The American Car, published by Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers, Template:ISBN-10

External links

- HOT ROD Covers - The 1950s - A look back at the covers of HOT ROD Magazine from The 1950s

- Old Car Brochures - The old car manual project