Helicase: Difference between revisions

→Active and passive helicases: The Boltzmann police nab another one |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

Many cellular processes ([[DNA replication]], [[Transcription (genetics)|transcription]], [[translation (biology)|translation]], [[Genetic recombination|recombination]], [[DNA repair]], [[ribosome biogenesis]]) involve the separation of nucleic acid strands. Helicases are often utilized to separate strands of a [[DNA]] [[double helix]] or a self-annealed [[RNA]] molecule using the energy from [[Adenosine triphosphate|ATP]] hydrolysis, a process characterized by the breaking of [[hydrogen bond]]s between [[Base pair|annealed nucleotide bases]]. They also function to remove nucleic acid-associated proteins and catalyze homologous [[DNA recombination]].<ref name="Patel2006">{{cite journal|last1=Patel|first1=S. S.|title=Mechanisms of Helicases|journal=Journal of Biological Chemistry|volume=281|issue=27|year=2006|pages=18265–18268|issn=0021-9258|doi=10.1074/jbc.R600008200}}</ref> Metabolic processes of RNA such as translation, transcription, [[ribosome biogenesis]], [[RNA splicing]], RNA transport, [[RNA editing]], and RNA degradation are all facilitated by helicases.<ref name=Patel2006 /> Helicases move incrementally along one [[nucleic acid]] strand of the duplex with a [[Directionality (molecular biology)|directionality]] and [[processivity]] specific to each particular enzyme. There are many helicases resulting from the great variety of processes in which strand separation must be catalyzed. Approximately 1% of eukaryotic genes code for helicases.<ref name="wu">{{cite journal |author=Wu Y |title=Unwinding and rewinding: double faces of helicase? |journal=J Nucleic Acids |volume=2012 |issue= |pages=140601 |year=2012 |pmid=22888405 |pmc=3409536 |doi=10.1155/2012/140601 |url=}}</ref> In humans, 95 non-redundant helicases are coded for in the genome, 64 RNA helicases and 31 DNA helicases.<ref name="umate">{{cite journal |author=Umate P, Tuteja N, Tuteja R |title=Genome-wide comprehensive analysis of human helicases |journal=Commun Integr Biol |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=118–37 |year=2011 |month=January |pmid=21509200 |pmc=3073292 |doi=10.4161/cib.4.1.13844 |url=}}</ref> |

Many cellular processes ([[DNA replication]], [[Transcription (genetics)|transcription]], [[translation (biology)|translation]], [[Genetic recombination|recombination]], [[DNA repair]], [[ribosome biogenesis]]) involve the separation of nucleic acid strands. Helicases are often utilized to separate strands of a [[DNA]] [[double helix]] or a self-annealed [[RNA]] molecule using the energy from [[Adenosine triphosphate|ATP]] hydrolysis, a process characterized by the breaking of [[hydrogen bond]]s between [[Base pair|annealed nucleotide bases]]. They also function to remove nucleic acid-associated proteins and catalyze homologous [[DNA recombination]].<ref name="Patel2006">{{cite journal|last1=Patel|first1=S. S.|title=Mechanisms of Helicases|journal=Journal of Biological Chemistry|volume=281|issue=27|year=2006|pages=18265–18268|issn=0021-9258|doi=10.1074/jbc.R600008200}}</ref> Metabolic processes of RNA such as translation, transcription, [[ribosome biogenesis]], [[RNA splicing]], RNA transport, [[RNA editing]], and RNA degradation are all facilitated by helicases.<ref name=Patel2006 /> Helicases move incrementally along one [[nucleic acid]] strand of the duplex with a [[Directionality (molecular biology)|directionality]] and [[processivity]] specific to each particular enzyme. There are many helicases resulting from the great variety of processes in which strand separation must be catalyzed. Approximately 1% of eukaryotic genes code for helicases.<ref name="wu">{{cite journal |author=Wu Y |title=Unwinding and rewinding: double faces of helicase? |journal=J Nucleic Acids |volume=2012 |issue= |pages=140601 |year=2012 |pmid=22888405 |pmc=3409536 |doi=10.1155/2012/140601 |url=}}</ref> In humans, 95 non-redundant helicases are coded for in the genome, 64 RNA helicases and 31 DNA helicases.<ref name="umate">{{cite journal |author=Umate P, Tuteja N, Tuteja R |title=Genome-wide comprehensive analysis of human helicases |journal=Commun Integr Biol |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=118–37 |year=2011 |month=January |pmid=21509200 |pmc=3073292 |doi=10.4161/cib.4.1.13844 |url=}}</ref> |

||

Helicases |

Helicases aWhereas [[DnaB]]-like helicases unwind [[DNA]] as donut-shaped [[hexamer]]s, other enzymes have been shown to be active as [[monomer]]s or [[protein dimer|dimer]]s. Studies have shown that helicases may act passively, waiting for uncatalyzed unwind Spiering MM, Benkovic SJ, Bensimon D, Croquette V|title=Real-time observation of bacteriophage T4 gp41 helicase reveals an unwinding mechanism |journal=PNAS |volume=104 |issue=50 |pages=19790–19795 |year=2007 |pmid=18077411 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0709793104 |pmc=2148377}}</ref> or can play an active role in catalyzing strand separation using the energy generated in ATP hydrolysis.<ref name=Johnson>{{cite journal |author=Johnson DS, Bai L, Smith BY, Patel SS, Wang MD |title=Single-molecule studies reveal dynamics of DNA unwinding by the ring-shaped t7 helicase |journal=Cell |volume=129 |issue=7 |pages=1299–309 |year=2007 |pmid=17604719 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.038 |pmc=2699903}}</ref> In the latter case, the helicase acts comparably to an active motor, unwinding and translocating along its substrate as a direct result of its ATPase activity.<ref name=physorg1>{{cite web |url=http://www.physorg.com/news102663442.html |title=Researchers solve mystery of how DNA strands separate |date=2007-07-03 |accessdate=2007-07-05}}</ref> Helicases may process much faster ''[[in vivo]]'' than ''[[in vitro]]'' due to the presence of accessory proteins that aid in the destabilization of the fork junction.<ref name=physorg1 /> |

||

===Activation barrier in helicase activity=== |

===Activation barrier in helicase activity=== |

||

Revision as of 00:05, 4 December 2012

| DNA helicase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 3.6.4.12 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| RNA helicase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 3.6.4.13 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

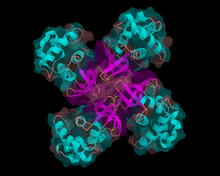

Helicases are a class of enzymes vital to all living organisms. They are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic acid phosphodiester backbone, separating two annealed nucleic acid strands (i.e., DNA, RNA, or RNA-DNA hybrid) using energy derived from ATP hydrolysis.

Function

Many cellular processes (DNA replication, transcription, translation, recombination, DNA repair, ribosome biogenesis) involve the separation of nucleic acid strands. Helicases are often utilized to separate strands of a DNA double helix or a self-annealed RNA molecule using the energy from ATP hydrolysis, a process characterized by the breaking of hydrogen bonds between annealed nucleotide bases. They also function to remove nucleic acid-associated proteins and catalyze homologous DNA recombination.[1] Metabolic processes of RNA such as translation, transcription, ribosome biogenesis, RNA splicing, RNA transport, RNA editing, and RNA degradation are all facilitated by helicases.[1] Helicases move incrementally along one nucleic acid strand of the duplex with a directionality and processivity specific to each particular enzyme. There are many helicases resulting from the great variety of processes in which strand separation must be catalyzed. Approximately 1% of eukaryotic genes code for helicases.[2] In humans, 95 non-redundant helicases are coded for in the genome, 64 RNA helicases and 31 DNA helicases.[3]

Helicases aWhereas DnaB-like helicases unwind DNA as donut-shaped hexamers, other enzymes have been shown to be active as monomers or dimers. Studies have shown that helicases may act passively, waiting for uncatalyzed unwind Spiering MM, Benkovic SJ, Bensimon D, Croquette V|title=Real-time observation of bacteriophage T4 gp41 helicase reveals an unwinding mechanism |journal=PNAS |volume=104 |issue=50 |pages=19790–19795 |year=2007 |pmid=18077411 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0709793104 |pmc=2148377}}</ref> or can play an active role in catalyzing strand separation using the energy generated in ATP hydrolysis.[4] In the latter case, the helicase acts comparably to an active motor, unwinding and translocating along its substrate as a direct result of its ATPase activity.[5] Helicases may process much faster in vivo than in vitro due to the presence of accessory proteins that aid in the destabilization of the fork junction.[5]

Activation barrier in helicase activity

Enzymatic helicase action, such as unwinding nucleic acids, is achieved through the lowering of the activation barrier (B) of each specific action.[6] The activation barrier is a result of various factors, and can be defined using the following equation, where N = number of unwound base pairs (bps), ΔGbp = free energy of base pair formation, Gint = reduction of free energy due to helicase, and Gƒ = reduction of free energy due to unzipping forces.[6]

- B = N (ΔGbp-Gint-Gƒ)

Factors that contribute to the height of the activation barrier include: specific nucleic acid sequence of the molecule involved, the number of base pairs involved, tension present on the replication fork, and destabilization forces.[6]

Active and passive helicases

The size of the activation of barrier to overcome by the helicase contributes to its classification of an active or passive helicase. In passive helicases, a significant activation barrier exists (which can be evaluated by finding B > kbT, where kb is Boltzmann's constant and T is temperature of the system).[6] Because of this significant activation barrier, its unwinding progression is largely affected by the sequence of nucleic acids within the molecule to unwind, and the presence of destabilization forces acting on the replication fork.[6] Certain nucleic acid combinations will decrease unwinding rates (i.e. guanine and cytosine), while various destabilizing forces can increase the unwinding rate.[6] In passive systems, the rate of unwinding (Vun) is less than the rate of translocation (Vtrans) (translocation along the single-stranded nucleic acid, ssNA).[6] Another way to view the passive helicase is its reliance on the transient unraveling of the base pairs at the replication fork to determine its rate of unwinding.[6] In active helicases, B < kbT, where the system lacks a significant barrier as the helicase is able to destabilize the nucleic acids, unwinding the double-helix at a constant rate, regardless of the nucleic acid sequence.[6] In active helicases, Vun is approximately equal to Vtrans.[6] Another way to view the active helicase is its ability to directly destabilize the replication fork to promote unwinding.[6]

Active helicases will show similar behavior when acting on both double-stranded nucleic acids, dsNA, or ssNA in regards to the rates of unwinding and rates of translocation, where in both systems Vun and Vtrans are approximately equal, i.e. Vun/ Vtrans ≈ 1.[6]

Structural features

The common function of helicases accounts for the fact that they display a certain degree of amino acid sequence homology; they all possess common sequence motifs located in the interior of their primary structure. These are thought to be specifically involved in ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis and translocation on the nucleic acid substrate. The variable portion of the amino acid sequence is related to the specific features of each helicase.

Based on the presence of defined helicase motifs, it is possible to attribute a putative helicase activity to a given protein, though the presence of a motif does not confirm the protein as a helicase. Conserved motifs do, however, support an evolutionary homology among enzymes. Based on the presence and the form of helicase motifs, helicases have been separated in 4 superfamilies and 2 smaller families. Some members of these families are indicated, with the organism from which they are extracted, and their function.

Superfamilies

Helicases have been classified in 6 major groups (superfamilies) based on the motifs and consensus sequences shared by the molecules.[7] Helicases that do not form a ring structure are included in superfamilies 1 and 2 and the ring forming helicases form part of superfamilies 3 to 6.[8] Helicases are also classified as α or β depending on if they work with single or double stranded DNA, α helicases work with single stranded DNA and β helicases work with double stranded DNA. They are also classified by translocation polarity. If translocation occurs 3’-5’ then the helicase is a Type A helicase or if translocation occurs 5’-3’ then it is a type B Helicase.[7]

- Superfamily 1 (SF1): In this group helicases can have either 3’-5’ or 5’-3’ translocation polarity.[7] This subgroup is at the same time subdivided in SF1A and SF1B Helicases.[7] The most known SF1A helicases are Rep and UvrD in gram-negative bacteria and PcrA helicase from gram-positive bacteria.[7] The most known Helicases in the SF1B group are RecD and Dda helicases.[7]

- Superfamily 2 (SF2): This is the largest group of helicases that are involved in varied cellular processes.[9][7] They are characterized by the presence of nine conserved motifs: Q, I, Ia, Ib and from II to VI.[9] This group is mainly composed of DEAD-box RNA helicases.[8] Some other helicases included in SF2 are the RecQ-like family and the Snf2-like enzymes.[7] Most ot the SF2 helicases are type A with a few exceptions such as the XPD family.[7]

- Superfamily 3 (SF3): Superfamily 3 consists of helicases encoded mainly by small DNA viruses and some large nucleocytoplasmic DNA viruses.[10][11] They have a 3’-5’ translocation directionality, meaning that they are all type A helicases.[7] The most known SF3 helicase is the papilloma virus E1 helicase.[7]

- Superfamily 4 (SF4): All SF4 family helicases have a type B polarity (5’-3’).[7] The most studied SF4 helicase is gp4 from bacteriophage T7.[7]

- Superfamily 6 (SF6): They contain the core AAA+ that is not included in the SF3 classification.[7] Some proteins in the SF6 group are: mini chromosome maintenance MCM, RuvB, RuvA and RuvC.[7]

Helicase disorders and diseases

ATRX helicase mutations

The ATRX gene encodes the ATP-dependent helicase, ATRX (also known as XH2 and XNP) of the SNF2 subgroup family, that is thought to be responsible for functions such as chromatin remodeling, gene regulation, and DNA methylation.[12][13][14][15] These functions assist in prevention of apoptosis, resulting in cortical size regulation, as well as a contribution to the survival of hippocampal and cortical structures, affecting memory and learning.[12] This helicase is located on the X chromosome (Xq13.1-q21.1), in the pericentromeric heterochromatin and binds to Heterochromatin protein 1.[12][14] Studies have shown that ATRX plays a role in rDNA methylation and is essential for embyonic development.[16] Mutations have been found throughout the ATRX protein, with over 90% of them being located in the zinc finger and helicase domains.[17] Mutations of ATRX can result in X-linked-alpha-thalassaemia-mental retardation (ATR-X syndrome).[12]

Various types of mutations found in ATRX have been found to be associated with ATR-X, including most commonly single-base missense mutations, as well as nonsense, frameshift, and deletion mutations.[15] Characteristics of ATR-X include: microcephaly, skeletal and facial abnormalities, mental retardation, genital abnormalities, seizures, limited language use and ability, and alpha-thalassemia.[12][16][18] The phenotype seen in ATR-X suggests that the mutation of ATRX gene causes the downregulation of gene expression, such as the alpha-globin genes.[18] It is still unknown what causes the expression of the various characteristics of ATR-X in different patients.[16]

XPD helicase point mutations

XPD (Xeroderma pigmentosum factor D, also known as protein ERCC2) is a 5'-3', Superfamily II, ATP-dependent helicase containing iron-sulphur cluster domains.[19][20] Inherited point mutations in XPD helicase have been shown to be associated with accelerated aging disorders such as Cockayne syndrome (CS) and trichothiodystrophy (TTD).[21] Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy are both developmental disorders involving sensitivity to UV light and premature aging, and Cockayne syndrome exhibits severe mental retardation from the time of birth.[21] The XPD helicase mutation has also been implicated in xeroderma pigmentosa (XP), a disorder characterized by sensitivity to UV light and resulting in a several 1000-fold increase in the development of skin cancer.[21]

XPD is an essential component of the TFIIH complex, a transcription and repair factor in the cell.[21][22][23][24][25] As part of this complex, it facilitates nucleotide excision repair by unwinding DNA.[21] TFIIH assists in repairing damaged DNA such as sun damage.[21][22][23][24][25] A mutation in the XPD helicase which helps form this complex and contributes to its function causes the sensitivity to sunlight seen in all three diseases, as well as the increased risk of cancer seen in XP and premature aging seen in trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome.[21]

XPD helicase mutations leading to trichothiodystrophy are found throughout the protein in various locations involved in protein-protein interactions.[21] This mutation results in an unstable protein due to its inability to form stabilizing interactions with other proteins at the points of mutations.[21] This, in turn, destabilizes the entire TFIIH complex which leads to defects with transcription and repair mechanisms of the cell.[21]

It has been suggested that XPD helicase mutations leading to Cockayne syndrome could be the result of mutations within XPD causing rigidity of the protein and subsequent inability to switch from repair functions to transcription functions due to a "locking" in repair mode.[21] This could cause the helicase to cut DNA segments meant for transcription.[21] Although current evidence points to a defect in the XPD helicase resulting in a loss of flexibility in the protein in cases of Cockayne syndrome, it is still unclear how this protein structure leads to the symptoms described in Cockayne syndrome.[21]

In xeroderma pigmentosa, the XPD helicase mutation exists at the site of ATP or DNA binding.[21] This results in a structurally functional helicase able to facilitate transcription, however it inhibits its function in unwinding DNA and DNA repair.[21] The lack of cell's ability to repair mutations, such as those caused by sun damage, is the cause of the high cancer rate in xeroderma pigmentosa patients.

RecQ family mutations

RecQ helicases (3'-5') belong to the Superfamily II group of helicases, which help to maintain stability of the genome and supress inappropriate recombination.[26][27] Deficiencies and/or mutations in RecQ family helicases display aberrant genetic recombination and/or DNA replication, which leads to chromosomal instability and an overall decreased ability to proliferate.[26] Mutations in RecQ family helicases BLM, RECQL4, and WRN, which play a role in regulating homologous recombination, have been shown to result in the autosomal recessive diseases Bloom syndrome (BS), Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (RTS), and Werner syndrome (WS), respectively.[27][28]

Bloom syndrome is characterized by a predisposition to cancer with early onset, with a mean age-of-onset of 24 years.[27][29] Cells of Bloom syndrome patients show a high frequency of reciprocal exchange between sister chromatids (SCEs) and excessive chromosomal damage.[30] There is evidence to suggest that BLM plays a role in rescuing disrupted DNA replication at replication forks.[30]

Werner syndrome is a disorder of premature aging, with symptoms including early onset of atherosclerosis and osteoporosis and other age related diseases, a high occurance of sarcoma, and death often occurring from myocardial infarction or cancer in the 4th to 6th decade of life.[27][31] Cells of Werner syndrome patients exhibit a reduced reproductive lifespan with chromosomal breaks and translocations, as well as large deletions of chromosomal components, causing genomic instability.[31]

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, also known as poikiloderma congenitale, is characterized by premature aging, skin and skeletal abnormalities, rash, poikiloderma, juvenile cataracts, and a predisposition to cancers such as osteosarcomas.[27][32] Chromosomal rearrangements causing genomic instability are found in the cells of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome patients.[32]

RNA helicases

RNA helicases and DNA helicases can be found together in all the helicase superfamilies except for SF6.[33] However, not all RNA helicases exhibit helicase activity as defined by enzymatic function, i.e., proteins of the Swi/Snf family. Although these proteins carry the typical helicase motifs, hydrolize ATP in a nucleic acid-dependent manner, and are built around a helicase core, in general, no unwinding activity is observed.[34]

RNA helicases that do exhibit unwinding activity have been characterized by at least two different mechanisms: canonical duplex unwinding and local strand separation. Canonical duplex unwinding is the stepwise directional separation of a duplex strand, as described above, for DNA unwinding. However, local strand separation occurs by a process wherein the helicase enzyme is loaded at any place along the duplex. This is usually aided by a single-stranded region of the RNA, and the loading of the enzyme is accompanied with ATP binding.[35] Once the helicase and ATP are bound, local strand separation occurs, which requires binding of ATP but not the actual process of ATP hydrolysis.[36] Presented with fewer base pairs the duplex then dissociates without further assistance from the enzyme. This mode of unwinding is used by DEAD-box helicases.[37]

DNA Helicase Discovery History

DNA helicases were first discovered in E. coli in 1976. The discoverers of this helicase described the molecule as a “DNA unwinding enzyme” that is “found to denature DNA duplexes in an ATP-dependent reaction, without detectably degrading”.[38] The first eukaryotic DNA helicase discovery was in 1978 and found in the lily plant.[39] Since then, DNA helicases were discovered and isolated in other bacteria, viruses, yeast, flies, and higher eukaryotes and has such been accordingly named as “prokaryotic”, “eukaryotic”, “bacteriophage”, and “viral”.[40] Below is a short description of the helicase discovery history:

- 1976 – Discovery and isolation of E. coli based DNA helicase[38]

- 1978 – Discovery of the first eukaryotic DNA helicases, isolated from the lily plant[39]

- 1982 – “T4 gene 41 protein” is the first reported bacteriophage DNA helicase[40]

- 1985 – First mammalian DNA helicases isolated from calf thymus[41]

- 1986 – SV40 large tumor antigen reported as a viral helicase (1st reported viral protein that was determined to serve as a DNA helicase)[42]

- 1986 – ATPaseIII, a yeast protein, determined to be a DNA helicase[43]

- 1988 – Discovery of seven conserved amino acid domains determined to be helicase motifs

- 1989 – Designation of DNA helicase Superfamily I and Superfamily II[44]

- 1990 - Isolation of a human DNA helicase[45]

- 1992 – Isolation of the first reported mitochondrial DNA helicase (from bovine brain)[46]

- 1996 – Report of the discovery of the first purified chloroplast DNA helicase from the pea[47]

- 2002 – Isolation and characterization of the first biochemically active malarial parasite DNA helicase - Plasmodium cynomolgi[48]

Diagnostic Tools for Helicase Measurement

Measuring/monitoring helicase activity

Various methods are used to measure helicase activity in vitro. These methods range from assays that are qualitative (assays that usually entail results that do not involve values or measurements) to quantitative (assays with numerical results that can be utilized in statistical and numerical analysis). In 1982-1983, the first direct biochemical assay was developed for measuring helicase activity.[49][50] This method was called a “strand displacement assay”.

- Strand displacement assay involves the radiolabeling of DNA duplexes. Following helicase treatment, the single-stranded DNA is visually detected as separate from the double-stranded DNA by non-denaturing PAGE electrophoresis. Following detection of the single-stranded DNA, the amount of radioactive tag that is on the single-stranded DNA is quantified to give a numerical value for the amount of double-stranded DNA unwinding.

- The strand displacement assay is acceptable for qualitative analysis, its inability to display results for more than a single time point, its time consumption, and its dependance on a radioactive bio-hazard for labeling warranted the need for development of diagnostics that can monitor helicase activity in real time.

Other methods were later developed that incorporated some, if not all of the following: high throughput mechanics, the use of less hazardous nucleotide labeling, faster reaction time/less time consumption, real-time monitoring of helicase activity (using kinetic measurement instead of endpoint/single point analysis). These methodologies include: "a rapid quench flow method, fluorescence based assays, filtration assays, a scintillation proximity assay, a time resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay, an assay based on flashplate technology, homogenous time-resolved fluorescence quenching assays, and electrochemiluminescence-based helicase assays".[51] With the used of specialized mathematical equations, some of these assays can be utilized to determine how many base paired nucleotides a helicase can break per hydrolysis of 1 ATP molecule.[52]

Commercially available diagnostic kits are also available. One such kit is the "Trupoint" diagnostic assay from PerkinElmer, Inc. This assay is a time-resolved fluorescence quenching assay that utilizes the PerkinEmer "SignalClimb" technology that is based on two labels which bind in close proximity to one another but on opposite DNA strands . One label is a fluorescent lanthanide chelate which serves as the label that is monitored through a adequate 96/384 well plate reader. The other label is a organic quencher molecule. The basis of this assay is the "quenching" or repressing of the lanthanide chelate signal by the organic quencher molecule when the two are in close proximity - as they would be when the DNA duplex is in its native state. Upon helicase activity on the duplex the quencher and lanthanide labels get separated as the DNA is unwound. This loss in proximity negates the quenchers ability to repress the lanthanide signal, causing a detectable increase in fluorescence that is representative of the amount of unwound DNA and can be used as a quantifiable measurement of helicase activity.

Determining Helicase Polarity

Helicase polarity, which is also deemed "directionality", is defined as the direction (characterized as 5'→3' or 3'→5') of helicase movement on single stranded DNA. This determination of polarity is vital in determining whether the tested helicase attaches to the DNA leading strand, or the DNA lagging strand. To characterize this helicase feature, a partially duplex DNA is utilized as the substrate which has a central single-stranded DNA region with different lengths of duplex regions of DNA (1 short region that runs 5'→3' and 1 longer region that runs 3'→5') on both sides of this region.[53] Once the helicase is added to that central single-stranded region, the polarity is determined by characterization on the newly formed single-stranded DNA.

See also

- chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein: CHD1, CHD1L, CHD2, CHD3, CHD4, CHD5, CHD6, CHD7, CHD8, CHD9

- DEAD box/DEAD/DEAH box helicase: DDX3X, DDX5, DDX6, DDX10, DDX11, DDX12, DDX58, DHX8, DHX9, DHX37, DHX40, DHX58

- ASCC3, BLM, BRIP1, DNA2, FBXO18, FBXO30, HELB, HELLS, HELQ, HELZ, HFM1, HLTF, IFIH1, NAV2, PIF1, RECQL, RTEL1, SHPRH, SMARCA4, SMARCAL1, WRN, WRNIP1

References

- ^ a b Patel, S. S. (2006). "Mechanisms of Helicases". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (27): 18265–18268. doi:10.1074/jbc.R600008200. ISSN 0021-9258.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wu Y (2012). "Unwinding and rewinding: double faces of helicase?". J Nucleic Acids. 2012: 140601. doi:10.1155/2012/140601. PMC 3409536. PMID 22888405.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Umate P, Tuteja N, Tuteja R (2011). "Genome-wide comprehensive analysis of human helicases". Commun Integr Biol. 4 (1): 118–37. doi:10.4161/cib.4.1.13844. PMC 3073292. PMID 21509200.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson DS, Bai L, Smith BY, Patel SS, Wang MD (2007). "Single-molecule studies reveal dynamics of DNA unwinding by the ring-shaped t7 helicase". Cell. 129 (7): 1299–309. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.038. PMC 2699903. PMID 17604719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Researchers solve mystery of how DNA strands separate". 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Manosas M, Xi XG, Bensimon D, Croquette V (2010). "Active and passive mechanisms of helicases". Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (16): 5518–26. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq273. PMC 2938219. PMID 20423906.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Martin Singleton, Mark S. Dillingham, and Dale B. Wigley (2007). "Structure and mechanism of Helicases and Nucleic Acid Translocases". The Annual Review of Biochemistry. 76: 23–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. PMID 17506634.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Margaret E. Fairman-Williams, Ulf-Peter Guenther and Echard Jankowsky (2010). "SF1 and SF2 helicases: family matters". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 20: 313–324. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.011. PMID 20456941.

- ^ a b Pavan Umate, Narendra Tuteja and Renu Tuteja (2011). "Genome-wide comprehensive análisis of human helicases". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 4: 118–137. doi:10.4161/cib.4.1.13844. PMID 21509200.

- ^ Koonin EV, Aravind L, Iyer LM (2001). "Common origin of four diverse families of large eukaryotic DNA viruses". J. Virol. 75 (23): 11720–34. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.23.11720-11734.2001. PMC 114758. PMID 11689653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koonin EV, Aravind L, Leipe DD, Iyer LM (2004). "Evolutionary history and higher order classification of AAA+ ATPases". J. Struct. Biol. 146 (1–2): 11–31. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2003.10.010. PMID 15037234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Ropers HH, Hamel BC (2005). "X-linked mental retardation". Nat. Rev. Genet. 6 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1038/nrg1501. PMID 15630421.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gibbons RJ, Picketts DJ, Villard L, Higgs DR (1995). "Mutations in a putative global transcriptional regulator cause X-linked mental retardation with alpha-thalassemia ATR-X syndrome". Cell. 80 (6): 837–45. PMID 7697714.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nextrprot Online Protein Database. " ATRX-Transcriptional regulator ATRX.", Retrieved on 12 November 2012.

- ^ a b Picketts DJ, Higgs DR, Bachoo S, Blake DJ, Quarrell OW, Gibbons RJ (1996). "ATRX encodes a novel member of the SNF2 family of proteins: mutations point to a common mechanism underlying the ATR-X syndrome". Hum. Mol. Genet. 5 (12): 1899–907. PMID 8968741.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Gibbons R (2006). "Alpha thalassaemia-mental retardation, X linked". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 1: 15. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-15. PMC 1464382. PMID 16722615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, Stevenson RE. PMID 20301622.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gibbons RJ, Picketts DJ, Villard L, Higgs DR (1995). "Mutations in a putative global transcriptional regulator cause X-linked mental retardation with alpha-thalassemia (ATR-X syndrome)". Cell. 80 (6): 837–45. PMID 7697714.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Wigley DB (2007). "Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76: 23–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. PMID 17506634.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rudolf J, Rouillon C, Schwarz-Linek U, White MF (2010). "The helicase XPD unwinds bubble structures and is not stalled by DNA lesions removed by the nucleotide excision repair pathway". Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (3): 931–41. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp1058. PMC 2817471. PMID 19933257.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Fan L, Fuss JO, Cheng QJ, Arvai AS, Hammel M, Roberts VA, Cooper PK, Tainer JA (2008). "XPD helicase structures and activities: insights into the cancer and aging phenotypes from XPD mutations". Cell. 133 (5): 789–800. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.030. PMC 3055247. PMID 18510924.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lainé JP, Mocquet V, Egly JM (2006). "TFIIH enzymatic activities in transcription and nucleotide excision repair". Meth. Enzymol. Methods in Enzymology. 408: 246–63. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08015-3. ISBN 9780121828134. PMID 16793373.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tirode F, Busso D, Coin F, Egly JM (1999). "Reconstitution of the transcription factor TFIIH: assignment of functions for the three enzymatic subunits, XPB, XPD, and cdk7". Mol. Cell. 3 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80177-X. PMID 10024882.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sung P, Bailly V, Weber C, Thompson LH, Prakash L, Prakash S (1993). "Human xeroderma pigmentosum group D gene encodes a DNA helicase". Nature. 365 (6449): 852–5. doi:10.1038/365852a0. PMID 8413672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Schaeffer L, Roy R, Humbert S, Moncollin V, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JH, Chambon P, Egly JM (1993). "DNA repair helicase: a component of BTF2 (TFIIH) basic transcription factor". Science. 260 (5104): 58–63. doi:10.1126/science.8465201. PMID 8465201.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hanada K, Hickson ID (2007). "Molecular genetics of RecQ helicase disorders". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64 (17): 2306–22. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7121-z. PMID 17571213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Opresko PL, Cheng WH, Bohr VA (2004). "Junction of RecQ helicase biochemistry and human disease". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (18): 18099–102. doi:10.1074/jbc.R300034200. PMID 15023996.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ouyang KJ, Woo LL, Ellis NA (2008). "Homologous recombination and maintenance of genome integrity: cancer and aging through the prism of human RecQ helicases". Mech. Ageing Dev. 129 (7–8): 425–40. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.003. PMID 18430459.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ellis NA, Groden J, Ye TZ, Straughen J, Lennon DJ, Ciocci S, Proytcheva M, German J (1995). "The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases". Cell. 83 (4): 655–66. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. PMID 7585968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Selak N, Bachrati CZ, Shevelev I, Dietschy T, van Loon B, Jacob A, Hübscher U, Hoheisel JD, Hickson ID, Stagljar I (2008). "The Bloom's syndrome helicase (BLM) interacts physically and functionally with p12, the smallest subunit of human DNA polymerase delta". Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (16): 5166–79. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn498. PMC 2532730. PMID 18682526.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gray MD, Shen JC, Kamath-Loeb AS, Blank A, Sopher BL, Martin GM, Oshima J, Loeb LA (1997). "The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase". Nat. Genet. 17 (1): 100–3. doi:10.1038/ng0997-100. PMID 9288107.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kitao S, Shimamoto A, Goto M, Miller RW, Smithson WA, Lindor NM, Furuichi Y (1999). "Mutations in RECQL4 cause a subset of cases of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome". Nat. Genet. 22 (1): 82–4. doi:10.1038/8788. PMID 10319867.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jankowsky E, Fairman-Williams ME (2010). "An introduction to RNA helicases: superfamilies, families, and major themes". In Jankowsky E (ed.). RNA Helicases (RSC Biomolecular Sciences). Cambridge, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 5. ISBN 1-84755-914-X.

- ^ Jankowsky E (2011). "RNA helicases at work: binding and rearranging". Trends Biochem. Sci. 36 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.008. PMC 3017212. PMID 20813532.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yang Q, Del Campo M, Lambowitz AM, Jankowsky E (2007). "DEAD-box proteins unwind duplexes by local strand separation". Mol. Cell. 28 (2): 253–63. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.016. PMID 17964264.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu F, Putnam A, Jankowsky E (2008). "ATP hydrolysis is required for DEAD-box protein recycling but not for duplex unwinding". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (51): 20209–14. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811115106. PMC 2629341. PMID 19088201.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jarmoskaite I, Russell R (2011). "DEAD-box proteins as RNA helicases and chaperones". Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2 (1): 135–52. doi:10.1002/wrna.50. PMC 3032546. PMID 21297876.

- ^ a b Abdel-Monem M, Dürwald H, Hoffmann-Berling H (1976). "Enzymic unwinding of DNA. 2. Chain separation by an ATP-dependent DNA unwinding enzyme". Eur. J. Biochem. 65 (2): 441–9. PMID 133023.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hotta Y, Stern H (1978). "DNA unwinding protein from meiotic cells of Lilium". Biochemistry. 17 (10): 1872–80. PMID 207302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Venkatesan M, Silver LL, Nossal NG (1982). "Bacteriophage T4 gene 41 protein, required for the synthesis of RNA primers, is also a DNA helicase". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (20): 12426–34. PMID 6288720.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hubscher, U. Stalder, H.P. (1985). Mammalian DNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 5471-5483.

- ^ Stahl H, Dröge P, Knippers R (1986). "DNA helicase activity of SV40 large tumor antigen". EMBO J. 5 (8): 1939–44. PMC 1167061. PMID 3019672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sugino A, Ryu BH, Sugino T, Naumovski L, Friedberg EC (1986). "A new DNA-dependent ATPase which stimulates yeast DNA polymerase I and has DNA-unwinding activity". J. Biol. Chem. 261 (25): 11744–50. PMID 3017945.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Donchenko AP, Blinov VM (1989). "Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes". Nucleic Acids Res. 17 (12): 4713–30. PMC 318027. PMID 2546125.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuteja N, Tuteja R, Rahman K, Kang LY, Falaschi A (1990). "A DNA helicase from human cells". Nucleic Acids Res. 18 (23): 6785–92. PMC 332732. PMID 1702201.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hehman GL, Hauswirth WW (1992). "DNA helicase from mammalian mitochondria". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (18): 8562–6. PMC 49960. PMID 1326759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tuteja N, Phan TN, Tewari KK (1996). "Purification and characterization of a DNA helicase from pea chloroplast that translocates in the 3'-to-5' direction". Eur. J. Biochem. 238 (1): 54–63. PMID 8665952.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuteja R, Malhotra P, Song P, Tuteja N, Chauhan VS (2002). "Isolation and characterization of an eIF-4A homologue from Plasmodium cynomolgi". Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 124 (1–2): 79–83. PMID 12387853.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Venkatesan M, Silver LL, Nossal NG (1982). "Bacteriophage T4 gene 41 protein, required for the synthesis of RNA primers, is also a DNA helicase". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (20): 12426–34. PMID 6288720.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matson SW, Tabor S, Richardson CC (1983). "The gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. Characterization of helicase activity". J. Biol. Chem. 258 (22): 14017–24. PMID 6315716.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuteja N, Tuteja R (2004). "Prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases. Essential molecular motor proteins for cellular machinery". Eur. J. Biochem. 271 (10): 1835–48. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04093.x. PMID 15128294.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sarlós K, Gyimesi M, Kovács M (2012). "RecQ helicase translocates along single-stranded DNA with a moderate processivity and tight mechanochemical coupling". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (25): 9804–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114468109. PMC 3382518. PMID 22665805.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Borowiec, J. (1996) DNA Replication in Eukaryotic Cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 545-574

External links

- DNA+Helicases at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- RNA+Helicases at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)