Origin of the Moon: Difference between revisions

Atethnekos (talk | contribs) Reverted 1 good faith edit by 174.31.227.243 using STiki |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[http://www.astrobio.net/pressrelease/4673/titanium-paternity-test-says-earth-is-the-moons-only-parent Titanium Paternity Test Says Earth is the Moon's Only Parent (University of Chicago)]</ref> which [[Giant impact hypothesis#Difficulties|conflicts]] with the moon forming far from Earth's orbit. |

[http://www.astrobio.net/pressrelease/4673/titanium-paternity-test-says-earth-is-the-moons-only-parent Titanium Paternity Test Says Earth is the Moon's Only Parent (University of Chicago)]</ref> which [[Giant impact hypothesis#Difficulties|conflicts]] with the moon forming far from Earth's orbit. |

||

To help explain problems with this, a new theory published in late 2012 posits two bodies five-times the size of Mars collided, then re-collided, forming a large disc of debris that eventually formed the Earth and Moon.<ref name=nasa1/> The paper was called “Forming a Moon with an Earth-like composition via a Giant Impact,” by R.M Canup.<ref name=nasa1/> |

To help explain problems with this, a new theory published in late 2012 posits two bodies five-times the size of Mars collided, then re-collided, forming a large disc of debris that eventually formed the Earth and Moon.<ref name=nasa1/> The paper was called “Forming a Moon with an Earth-like composition via a Giant Impact,” by R.M Canup.<ref name=nasa1/> |

||

A late 2012 study on the depletion of [[zinc]] isotopes on the Moon, supported "the giant impact origin for the Earth and moon".<ref>[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v490/n7420/full/nature11507.html Paniello, et al. - Zinc isotopic evidence for the origin of the Moon]</ref> |

A late 2012 study on the depletion of [[zinc]] isotopes on the Moon, supported "the giant impact origin for the Earth and moon".<ref>[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v490/n7420/full/nature11507.html Paniello, et al. - Zinc isotopic evidence for the origin of the Moon]</ref> |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

In 2013, a study was released that indicated water in lunar magma was 'indistinguishable' from [[carbonaceous chondrite]]s and nearly the same as Earth's, based on the [[Isotopic signature|composition of isotopes]].<ref>http://blogs.airspacemag.com/moon/2013/05/earth-moon-a-watery-double-planet/ Earth-Moon: A Watery “Double-Planet”]</ref><ref>[http://www.sciencemag.org/content/340/6138/1317.abstract A. Saal, et al - Hydrogen Isotopes in Lunar Volcanic Glasses and Melt Inclusions Reveal a Carbonaceous Chondrite Heritage]</ref> |

In 2013, a study was released that indicated water in lunar magma was 'indistinguishable' from [[carbonaceous chondrite]]s and nearly the same as Earth's, based on the [[Isotopic signature|composition of isotopes]].<ref>http://blogs.airspacemag.com/moon/2013/05/earth-moon-a-watery-double-planet/ Earth-Moon: A Watery “Double-Planet”]</ref><ref>[http://www.sciencemag.org/content/340/6138/1317.abstract A. Saal, et al - Hydrogen Isotopes in Lunar Volcanic Glasses and Melt Inclusions Reveal a Carbonaceous Chondrite Heritage]</ref> |

||

GIH theory was again challenged in September 2013,<ref>{{cite journal | journal = Science | author = Daniel Clery | title = Impact Theory Gets Whacked | volume = 342 | page = 183 | date = 11 October 2013}}</ref> with a growing sense that lunar origins are more complicated.<ref name=clery>http://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6155/183 Daniel Clery -Impact Theory Gets Whacked]</ref> |

|||

==Other hypotheses== |

==Other hypotheses== |

||

Revision as of 22:38, 9 December 2013

Origin of the Moon refers to any of the various explanations for the formation of the Moon, Earth's natural satellite. The leading theory has been the giant impact hypothesis.[1] However, research continues on this matter, and there are a number of variations and alternatives.[1] Other proposed scenarios include captured body, fission, formed together (condensation theory), planetesimal collisions (formed from asteroid-like bodies), and collision theories.[2]

The standard GIH (Giant Impact Hypothesis) suggests a Mars-sized body called Theia impacted Earth, creating a large debris ring around the Earth which then formed the system.[1] However, the Moon's oxygen isotopic ratios seem to be essentially identical to Earth's.[3] Oxygen isotopic ratios, which may be measured very precisely, yield a unique and distinct signature for each solar system body.[4] If Theia had been a separate proto-planet, it probably would have had a different oxygen isotopic signature from Earth, as would the ejected mixed material.[5] Also, the Moon's titanium isotope ratio (50Ti/47Ti) appears so close to the Earth's (within 4 ppm), that little if any of the colliding body's mass could likely have been part of the Moon.[6][7]

Giant impact hypothesis

One of the challenges to the longstanding theory of the collision, is that a Mars-sized impacting body, whose composition likely would have differed substantially from that of Earth, likely would have left Earth and the moon with different chemical compositions, which they are not.

NASA[1]

The most widely accepted explanation for the origin of the Moon involves a collision of two protoplanetary bodies during the early accretional period of Solar System evolution. This "giant impact hypothesis", which became popular in 1984, satisfies the orbital conditions of the Earth and Moon and can account for the relatively small metallic core of the Moon. Collisions between planetesimals are now recognized to lead to the growth of planetary bodies early in the evolution of the Solar System, and in this framework it is inevitable that large impacts will sometimes occur when the planets are nearly formed. It is thought to have originated in the 1940s with Reginald Aldworth Daly, a Canadian professor at Harvard.

The hypothesis requires a collision between a body about 90% the present size of the Earth, and another the diameter of Mars (half of the terrestrial radius and a tenth of its mass). The colliding body has sometimes been referred to as Theia, the mother of Selene, the Moon goddess in Greek mythology. This size ratio is needed in order for the resulting system to possess sufficient angular momentum to match the current orbital configuration. Such an impact would have put enough material into orbit about the Earth to have eventually accumulated to form the Moon.

Computer simulations show a need for a glancing blow, which causes a portion of the collider to form a long arm of material that then shears off. The asymmetrical shape of the Earth following the collision then causes this material to settle into an orbit around the main mass. The energy involved in this collision is impressive: trillions of tons of material would have been vaporized and melted. In parts of the Earth the temperature would have risen to 10,000°C (18,000°F).

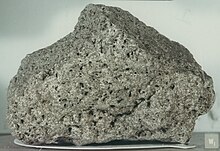

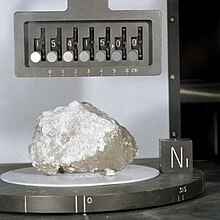

The Moon's relatively small iron core is explained by Theia's core accreting into Earth's. The lack of volatiles in the lunar samples is also explained in part by the energy of the collision. The energy liberated during the reaccreation of material in orbit about the Earth would have been sufficient to melt a large portion of the Moon, leading to the generation of a magma ocean.

The newly formed moon orbited at about one-tenth the distance that it does today, and became tidally locked with the Earth, where one side continually faces toward the Earth. The geology of the Moon has since been more independent of the Earth. While this hypothesis explains many aspects of the Earth-Moon system, there are still a few unresolved problems facing it, such as the Moon's volatile elements not being as depleted as expected from such an energetic impact.[8]

Another issue is Lunar and Earth isotope comparisons. In 2011, the most precise measurement yet of the isotopic signatures of lunar rocks was published.[3] Surprisingly, the Apollo lunar samples carried an isotopic signature identical to Earth rocks, but different from other Solar system bodies. Since most of the material that went into orbit to form the Moon was thought to come from Theia, this observation was unexpected. In 2007, researchers from Caltech showed that the likelihood of Theia having an identical isotopic signature as the Earth was very small (<1 percent).[9] Published in 2012, an analysis of titanium isotopes in Apollo lunar samples showed that the Moon has the same composition as the Earth[10] which conflicts with the moon forming far from Earth's orbit.

To help explain problems with this, a new theory published in late 2012 posits two bodies five-times the size of Mars collided, then re-collided, forming a large disc of debris that eventually formed the Earth and Moon.[1] The paper was called “Forming a Moon with an Earth-like composition via a Giant Impact,” by R.M Canup.[1]

A late 2012 study on the depletion of zinc isotopes on the Moon, supported "the giant impact origin for the Earth and moon".[11]

In 2013, a study was released that indicated water in lunar magma was 'indistinguishable' from carbonaceous chondrites and nearly the same as Earth's, based on the composition of isotopes.[12][13]

GIH theory was again challenged in September 2013,[14] with a growing sense that lunar origins are more complicated.[15]

Other hypotheses

| Density[16] | |||||||

| Body | Density | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 5.4 g/cm3 | ||||||

| Venus | 5.2 g/cm3 | ||||||

| Earth | 5.5 g/cm3 | ||||||

| the Moon | 3.3 g/cm3 | ||||||

Capture

This hypothesis states that the Moon was captured by the Earth.[17] This was popular until the 1980s, and some things in favor of this model include the Moon's size, orbit, and tidal locking.[17]

One problem is understanding the capture mechanism.[17] A close encounter with Earth typically results in either collision or altered trajectories. For this hypothesis to function, there might have been a large atmosphere extended around the primitive Earth, which would be able to slow the movement of the Moon before it could escape. That hypothesis may also explain the irregular satellite orbits of Jupiter and Saturn.[18] In addition, this hypothesis has difficulty explaining the essentially identical oxygen isotope ratios of the two worlds.[3]

Fission

This is the idea that an ancient, rapidly spinning Earth expelled a piece of its mass.[17] This was proposed by George Darwin (son of the famous biologist Charles Darwin) in the 1800s and retained some popularity until Apollo.[17] The Austrian Geologist Otto Ampherer in 1925 also suggested the emerging of the moon as cause for continental drift.[19]

It was proposed that the Pacific Ocean represented the scar of this event.[17] However, today it is known that the oceanic crust that makes up this ocean basin is relatively young, about 200 million years old and less, whereas the Moon is much older because it does not consist of oceanic crust but of mantle-material that originated inside the proto-earth in Precambrian.[6] However, the assumption that the Pacific is not the result of lunar creation does not disprove the fission hypothesis.[citation needed] This hypothesis also cannot account for the angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system.[citation needed]

Accretion

This hypothesis states that the Earth and the Moon formed together as a double system from the primordial accretion disk of the Solar System.[citation needed] The problem with this hypothesis is that it does not explain the angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system or why the Moon has a relatively small iron core compared to the Earth (25% of its radius compared to 50% for the Earth).[citation needed]

Georeactor explosion

A more radical alternative hypothesis, published in 2010, proposes that the Moon may have been formed from the explosion of a georeactor located along the core-mantle boundary at the equatorial plane of the rapidly rotating Earth. This hypothesis could explain the compositional similarities.[20]

Additional theories and studies

In 2011, it was theorized that a second moon existed 4.5 billion years ago, and later impacted the Moon, as a part of the accretion process in the formation of the Moon.[21]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f NASA Lunar Scientists Develop New Theory on Earth and Moon Formation

- ^ Theories of Formation for the Moon

- ^ a b c Wiechert, U.; et al. (2001). "Oxygen Isotopes and the Moon-Forming Giant Impact". Science. 294 (12). Science (journal): 345–348. Bibcode:2001Sci...294..345W. doi:10.1126/science.1063037. PMID 11598294. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "wiechert" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Scott, Edward R. D. (December 3, 2001). "Oxygen Isotopes Give Clues to the Formation of Planets, Moons, and Asteroids". Planetary Science Research Discoveries (PSRD). Bibcode:2001psrd.reptE..55S. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Nield, Ted (2009). "Moonwalk" (PDF). Geological Society of London. p. 8. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zhang, Junjun (25 March 2012). "The proto-Earth as a significant source of lunar material". Nature Geoscience. 5: 251–255. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..251Z. doi:10.1038/ngeo1429.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Koppes, Steve (March 28, 2012). "Titanium paternity test fingers Earth as moon's sole parent". Zhang, Junjun. The University of Chicago. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ J. H. Jones. "TESTS OF THE GIANT IMPACT HYPOTHESIS" (PDF). Origin of the Earth and Moon Conference. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Pahlevan, Kaveh; Stevenson, David (2007). "Equilibration in the Aftermath of the Lunar-forming Giant Impact". EPSL. 262 (3–4): 438–449. arXiv:1012.5323. Bibcode:2007E&PSL.262..438P. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.055.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Titanium Paternity Test Says Earth is the Moon's Only Parent (University of Chicago)

- ^ Paniello, et al. - Zinc isotopic evidence for the origin of the Moon

- ^ http://blogs.airspacemag.com/moon/2013/05/earth-moon-a-watery-double-planet/ Earth-Moon: A Watery “Double-Planet”]

- ^ A. Saal, et al - Hydrogen Isotopes in Lunar Volcanic Glasses and Melt Inclusions Reveal a Carbonaceous Chondrite Heritage

- ^ Daniel Clery (11 October 2013). "Impact Theory Gets Whacked". Science. 342: 183.

- ^ http://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6155/183 Daniel Clery -Impact Theory Gets Whacked]

- ^ The Formation of the Moon

- ^ a b c d e f Lunar Origin

- ^ Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007), "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 45: 261–295, arXiv:astro-ph/0703059, Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..261J, doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459

- ^ Die Naturwissenschaften, July 1925 (in German)

- ^ Edwards, Lin (January 28, 2010), "The Moon may have formed in a nuclear explosion", PhysOrg.com, Omicron Technology Limited, retrieved 2012-04-18

- ^ doi:10.1038/nature10289

External links

- Lunar formation Case Western Reserve University

- The Once and Future Moon (September 28, 2012)

- Nature - Moon-forming impact theory rescued