Homosexuality in ancient Greece: Difference between revisions

Josiah Rowe (talk | contribs) authorship of OCD entry |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{disputed}} |

|||

{{unreferenced}} |

|||

In [[classical antiquity]], writers such as [[Herodotus]],<ref>Herodotus ''Histories'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Hdt.+1.135&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126 1.135]</ref> [[Plato]],<ref>Plato, ''Phaedrus'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0174:text=Phaedrus 227a]</ref> [[Xenophon]],<ref>Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Xen.+Mem.+2.6.28&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0208 2.6.28], ''Symposium'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Xen.+Sym.+8&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0212 8]</ref> [[Athenaeus]]<ref>Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistae'' [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/pwh/athenaeus13.html 13:601-606]</ref> and many others explored aspects of same-sex love in ancient Greece. |

In [[classical antiquity]], writers such as [[Herodotus]],<ref>Herodotus ''Histories'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Hdt.+1.135&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126 1.135]</ref> [[Plato]],<ref>Plato, ''Phaedrus'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0174:text=Phaedrus 227a]</ref> [[Xenophon]],<ref>Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Xen.+Mem.+2.6.28&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0208 2.6.28], ''Symposium'' [http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Xen.+Sym.+8&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0212 8]</ref> [[Athenaeus]]<ref>Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistae'' [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/pwh/athenaeus13.html 13:601-606]</ref> and many others explored aspects of same-sex love in ancient Greece. |

||

Revision as of 12:05, 28 August 2006

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. |

In classical antiquity, writers such as Herodotus,[1] Plato,[2] Xenophon,[3] Athenaeus[4] and many others explored aspects of same-sex love in ancient Greece.

The most widespread and socially significant form of same-sex sexual relations in ancient Greece was between between adult men and adolescent boys, known as pederasty. Love between adult men was generally discouraged and ridiculed, but there are many records of such couples. It is unclear how love between women was regarded in the general society, but examples do exist as far back as the time of Sappho.[5]

Context

The ancient Greeks did not conceive of sexual orientation as a social identifier, as Western societies do today. In the ancient Greek context, the terms "homosexual" and "heterosexual" are properly used only to describe activities, not identities. Greek society did not distinguish sexual desire or behavior by to the gender of the participants, but by the extent to which such desire or behavior conformed to social norms. These norms were based on gender, age and social status.[5]

The understanding of male sexual activity in ancient Greek society was highly polarized into "active" and "passive" partners, penetrator and penetrated. (There is little extant source material on how females viewed sexual activity.) This active/passive polarization was associated with dominant and submissive social roles: the active role was associated with masculinity, higher social status and adulthood, while the passive role was associated with femininity, lower social status and youth. This, not the gender of the partners, was the most important form of categorization for sexual roles and activities.[5]

In general, any sexual activity in which a male penetrated a social inferior was regarded as normal. "Social inferiors" could include women, male youths, foreigners, prostitutes and/or slaves. Being penetrated, especially by a social inferior, was considered potentially shameful.[5]

Pederasty

- Main article: Pederasty in ancient Greece

The most common form of same-sex relationships between males in Greece was "paiderastia" meaning "boy love". It was a relationship between an older male and a youth around twelve to twenty. In Athens the older man was called erastes, he was to educate, protect, love, and provide a role model for his beloved. His beloved was called eromenos whose reward for his lover lay in his beauty, youth, and promise.

Elaborate social protocols existed to protect youths from the shame associated with being sexually penetrated. The eromenos was supposed to respect and honor the erastes, but not to desire him sexually. Although being courted by an older man was practically a rite of passage for young men, a youth who was seen to reciprocate the erotic desire of his erastes faced considerable social stigma.[5]

The ancient Greeks, in the context of the pederastic city-states, were the first to describe, study, systematize, and establish pederasty as a social and educational institution. It was an important element in civil life, the military, philosophy and the arts.[6] There is some debate between scholars about whether pederasty was widespread in all social classes, or largely limited to the aristocracy.

The morality of pederasty was largely unquestioned in ancient Greece. One notable exception is Plato's Laws, in which both pederasty and female homosexuality are described as "against nature"; however, the speakers in this dialogue acknowledge that an effort to abolish pederasty would be unpopular in most Greek city-states.[7]

In the military

- Main article:Homosexuality in the militaries of ancient Greece.

The Sacred Band of Thebes, a separate military unit reserved only for men and their beloved boys, is usually considered as the prime example of how the ancient Greeks used relationships between soldiers in a troop to boost their fighting spirit. The Thebans attributed to the Sacred Band the power of Thebes for the generation before its fall to Philip II of Macedon, who was so impressed with their bravery during battle, he erected a monument that still stands today on their gravesite. He also gave a harsh criticism of the Spartan views of the band:

- "Perish miserably they who think that these men did or suffered aught disgraceful."

Pammenes' opinion, according to Plutarch, was that

- "Homer's Nestor was not well skilled in ordering an army when he advised the Greeks to rank tribe and tribe... he should have joined lovers and their beloved. For men of the same tribe little value one another when dangers press; but a band cemented by friendship grounded upon love is never to be broken."

These bonds, perhaps somewhat inspired by episodes from Greek mythology, such as the heroic relationship between Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad, were thought to boost morale as well as bravery. They typically took the form of pederasty, with more egalitarian relationships being rarer. Such relationships were documented by many Greek historians and in philosophical discourses, as well as in offhand remarks such as Philip II of Macedon's recorded by Plutarch demonstrates:

- "It is not only the most warlike peoples, the Boeotians, Spartans, and Cretans, who are the most susceptible to this kind of love but also the greatest heroes of old: Meleager, Achilles, Aristomenes, Cimon, and Epaminondas."

During the Lelantine War between the Eretrians and the Chalcidians, before a decisive battle the Chalcidians called for the aid of a warrior named Cleomachus. Cleomachus answered their request and brought his lover along with him to watch. He charged against the Eretians and brought the Chalcidians to victory at the cost of his own life. It was said he was inspired with love during the battle. Afterwards the Chalcidians erected a tomb for him in their marketplace and adopted pederasty.

Love between adult men

- Main article: Homosexuality

Given the importance of asymmetry in the ancient Greek concept of sexuality, love between adult men of comparable social status was considered highly problematic, and often associated with social stigma. However, examples of such love are occasionally found in the historical record.

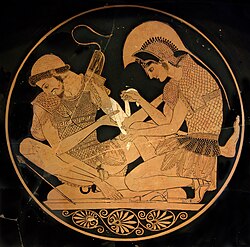

Achilles and Patroclus

- Main article: Achilles and Patroclus

The first recorded appearance of love between adult men, albeit in a non-sexual form, was in the Iliad (800 BC). The intentions of the Iliad have been a subject of much debate. An abundance of evidence exists that by the beginning of the Hellenistic era (480 BC) the Iliad’s heroes Achilles and Patroclus were pederastic icons. Since the ancient Greeks were uncomfortable with any perception of Patroclus and Achilles as adult equals, they tried to establish a clear age difference between the two. There was disagreement on whom to make the erastes and whom the eromenos, since the Homeric tradition made Patroclus out to be older but Achilles dominant. Other ancients claimed that Achilles and Patroclus were simply close friends.

Aeschylus in the tragedy Myrmidons made Achilles the protector since he had avenged his love’s death even though the gods told him it would cost his own life. However Phaedrus asserts that Homer emphasized the beauty of Achilles which would qualify him, not Patroclus, as “eromenos”.

Another mythical couple who are represented as coevals is that of Orestes and Pylades.

Historical adult male couples

Many historical male couples are known, where both partners were adults. Among these is the love between Euripides, in his seventies, and Agathon, already in his forties. The love between Alexander the Great and his childhood friend, Hephaistion is generally regarded as being of the same order.

Sapphic love

- Main article: Lesbian

Sappho, a poet from the island of Lesbos, was mistress of a school of girls and wrote love poems to many of her young students, with whom she often fell in love and who often reciprocated her feelings. She is thought to have written close to 12,000 lines of poetry on her love for other women. Of these, only about 600 lines have survived. As a result of her fame in antiquity, she and her land have become emblematic of love between women. Such pedagogic erotic relationships are also documented for Sparta, together with athletic nudity for women. Another source is Plato's Symposium, which speaks of women who "do not care for men, but have female attachments." In general, however, the historical record of same-sex love between women is sparse.

Scholarship and controversy

After a long hiatus marked by censorship of homosexual themes,[8] modern historians picked up the thread, starting with Erich Bethe in 1907 and continuing with K. J. Dover and many others. These scholars have shown that same-sex relations were openly practiced, largely with official sanction, in many areas of life from the 7th century BC until the Roman era.

Although this perspective is the scholarly consensus in North America and Northern Europe, a small but vocal minority maintains that homosexual behavior was not commonplace in Ancient Greece.[9] These scholars argue that certain parts of Greek literature have been interpreted in such a way to make it seem as if homosexuality was a common practice. Mainstream classics scholars reject these arguments as wilful misinterpretation, but both opponents of LGBT rights and Greek nationalists have latched on to them for political purposes.

The subject has caused controversy in modern Greece. In 2002, a conference on Alexander the Great was stormed as a paper about his homosexuality was about to be presented. When the film Alexander, which depicted Alexander as romantically involved with both men and women, was released in 2004, 25 Greek lawyers threatened to sue the film's makers,[10] but relented after attending an advanced screening of the film.[11] The movie was a financial disaster in Greece, where it played for only four days.

See also

Notes

- ^ Herodotus Histories 1.135

- ^ Plato, Phaedrus 227a

- ^ Xenophon, Memorabilia 2.6.28, Symposium 8

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 13:601-606

- ^ a b c d e Oxford Classical Dictionary entry on homosexuality, pp.720–723; entry by David M. Halperin.

- ^ Golden M. - Slavery and homosexuality in Athens. Phoenix 1984 XXXVIII : 308-324

- ^ Plato, Laws 636, 838–841

- ^ Rictor Norton, Critical Censorship of Gay Literature

- ^ Flaceliere, pp. 140-141

- ^ "Bisexual Alexander angers Greeks". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 2004-11-22. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Greek lawyers halt Alexander case". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 2004-12-03. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

References

- Greek Homosexuality, by Kenneth J. Dover; New York; Vintage Books, 1978. ISBN 0394742249

- One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love by David Halperin; Routeledge, 1989. ISBN 0415900972]]

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary, third edition. Simon Halperin and Antony Spawforth, eds.; Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-866172-X

- Homosexuality in Greece and Rome, by Thomas K. Hubbard; U. of California Press, 2003. [1] ISBN 0520234308

- Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece by William A. Percy, III. University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 0252022092

- Love in Ancient Greece by Flaceliere, Robert; New York; Crown Publications, 1962. ASIN B000H86W2A