1889–1890 pandemic: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Matthiaspaul (talk | contribs) m Matthiaspaul moved page 1889–90 flu pandemic to 1889–1890 flu pandemic over redirect: 4-digit years per MOS |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 17:59, 26 March 2020

A request that this article title be changed to 1889–90 influenza pandemic is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

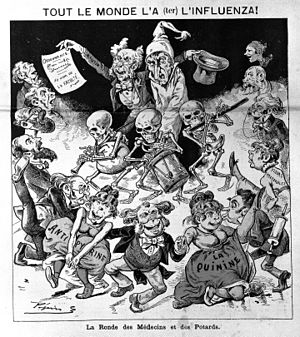

The 1889–1890 flu pandemic, better known as the "Asiatic flu" or "Russian flu" was a deadly influenza pandemic that killed about 1 million people worldwide.[1][2]

This was the last great pandemic of the 19th century.[3] It should not be confused with the 1977–1978 epidemic caused by Influenza A/USSR/90/77 H1N1, which was also called Russian flu.

The most reported effects of the pandemic took place October 1889 – December 1890, with recurrences March – June 1891, November 1891 – June 1892, winter 1893–1894 and early 1895. For some time the virus strain responsible was conjectured (but not proven) to be Influenza A virus subtype H2N2.[4][5] More recently, the strain was asserted to be Influenza A virus subtype H3N8.[6]

Outbreak and spread

Modern transport infrastructure assisted the spread of the 1889 influenza. The 19 largest European countries, including the Russian Empire, had 202,887 km of railroads and transatlantic travel by boat took less than six days (not significantly different than current travel time by air, given the time scale of the global spread of a pandemic).[6]

First reported in Bukhara, Russian Empire, in May 1889,[7][8] by November that year the epidemic had reached Saint Petersburg.[9] In four months it had spread throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Deaths peaked in Saint Petersburg on December 1, 1889, and in the United States during the week of January 12, 1890. The median time between the first reported case and peak mortality was five weeks.[6] In Malta, the Asiatic Flu took hold between January 1889 and March 1890, with a fatality rate of 4% (39 deaths), and a resurgence in January-May 1892 with 66 fatalities (3.3% case fatality).[10] A result of the Asiatic Flu in Malta is that influenza became for the first time a compulsorily notifiable illness.[11]

Identification of virus subtype responsible

Researchers have tried for many years to identify the subtypes of Influenza A responsible for the 1889–1890, 1898–1900 and 1918 epidemics. Initially, this work was primarily based on "seroarcheology"—the detection of antibodies to influenza infection in the sera of elderly people—and it was thought that the 1889–1890 pandemic was caused by Influenza A subtype H2, the 1898–1900 epidemic by subtype H3, and the 1918 pandemic by subtype H1.[13] With the confirmation of H1N1 as the cause of the 1918 flu pandemic following identification of H1N1 antibodies in exhumed corpses,[14] reanalysis of seroarcheological data has indicated that Influenza A subtype H3 (possibly the H3N8 subtype), is the most likely cause for the 1889–1890 pandemic.[6][15]

Notable deaths

Initial pandemic

- 1 January 1890 Henry R. Pierson

- 15 January 1890 Walker Blaine

- 22 January 1890 Adam Forepaugh

- 22 February 1890 Bill Blair

- 12 March 1890 William Allen (VC 1879)

- 26 March 1890 Afrikan Spir

- 23 May 1890 Louis Artan

- 19 July 1890 James P. Walker

Recurrences

- 23 January 1891 Prince Baudouin of Belgium[a]

- 10 February 1891 Sofya Kovalevskaya

- 18 March 1891 William Herndon

- 8 May 1891 Helena Blavatsky

- 15 May 1891 Edwin Long

- 3 June 1891 Oliver St John

- 9 June 1891 Henry Gawen Sutton

- 1 July 1891 Frederic Edward Manby

- 20 December 1891 Grisell Baillie

- 28 December 1891 William Arthur White

- 8 January 1892 John Tay

- 10 January 1892 John George Knight

- 12 January 1892 Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau

- 14 January 1892 Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, grandson of Queen Victoria

- 17 January 1892 Charles A. Spring

- 20 January 1892 Douglas Hamilton

- 12 February 1892 Thomas Sterry Hunt

- 15 April 1892 Amelia Edwards

- 5 May 1892 Gustavus Cheyney Doane

- 24 May 1892 Charles Arthur Broadwater

- 10 June 1892 Charles Fenerty

- 21 April 1893 Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby

- 7 August 1893 Thomas Burges

- 31 August 1893 William Cusins

- 15 December 1893 Samuel Laycock

- 16 December 1893 Tom Edwards-Moss

- 3 January 1894 Hungerford Crewe, 3rd Baron Crewe

- 24 January 1894 Constance Fenimore Woolson[b]

- 14 March 1894 John T. Ford

- 19 June 1894 William Mycroft

- 19 February 1895 John Hulke

- 1 March 1895 Frederic Chapman

- 5 March 1895 Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet

- 20 March 1895 James Sime

- 24 March 1895 John L. O'Sullivan

- 2 August 1895 Joseph Thomson

See also

- Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company – Case in English contract law, concerning an advertisement of 1891 for a putative flu remedy

Footnotes

References

- ^ "influenza". Volume 2 of Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Social Issues. ABC-CLIO. 2010. p. 1510. ISBN 0313392056. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic flu killed roughly one million individuals

- ^ Michelle Harris Williams; Michael Anne Preas. "Influenza and Pneumonia Basics Facts and Fiction" (PDF). DDA health - Maryland.gov. University of Maryland. p. "Pandemics". Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Asiatic Flu 1889-1890 1 million

- ^ FARSHID S. GARMAROUDI (30 October 2007). "THE LAST GREAT UNCONTROLLED PLAGUE OF MANKIND". Science Creative Quarterly. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic flu, 1889-1890: It was the last great pandemic of the nineteenth century.

- ^ Hilleman 2002, p. 3068.

- ^ Madrigal 2010.

- ^ a b c d Valleron et al. 2010.

- ^ Jeffrey R. Ryan, ed. (2008). Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Planning and Community Preparedness. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 1420060880. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic Flu of 1889-1890 was first reported in Bukhara, Russia

- ^ "Pandemic Planning: Information for Georgia Public School Districts" (PDF). Georgia Department of Education. Richard Woods, State School Superintendent GDE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic Flu was first reported in May of 1889 in Russia

- ^ "THE 1889 RUSSIAN FLU IN THE NEWS". Circulating Now from the N.I.H. National Institutes of Health. 13 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

In November 1889, a rash of cases of influenza-like-illness appeared in St. Petersburg, Russia. Soon, the "Russia Influenza" spread

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles (2005). "Past Influenza pandemics and their effect in Malta". Malta Medical Journal. 17 (3): 16–19. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

1889-90 pandemic – The Asiatic Flu [...] by the end of March 1890. The case fatality rate approximated 4.0% [Table 1]. A resurgence of the infection became apparent in January-May 1892 with a total of 2017 reported cases and 66 deaths [case fatality rate 3.3%]

- ^ Rebekah Cilia (15 March 2020). "How Malta dealt with past influenza pandemics, with today's being 'inevitable'". The Malta Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Compulsory notification of infectious disease [...] Influenza was made a notifiable infection on the 20th January 1890 with the appearance of 1889-90, Asiatic Flu

- ^ Parsons 1891.

- ^ Dowdle 1999, p. 820.

- ^ Dowdle 1999, p. 821.

- ^ Dowdle 1999, p. 825.

Sources

- Bäumler, Christian (1890), Ueber die Influenza von 1889 und 1890 [On the influenza of 1889 and 1890)] (in German)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 552–556.

- Dowdle, W.R. (1999), "Influenza A virus recycling revisited", Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 77 (10), Geneva: WHO: 820–8, PMC 2557748, PMID 10593030

- Hilleman, Maurice R. (August 19, 2002), "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control.", Vaccine, 20 (25–26), Elsevier: 3068–3087, doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2, PMID 12163258

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Madrigal, Alexis (April 26, 2010). "1889 Pandemic Didn't Need Planes to Circle Globe in 4 Months". Wired Science. Archived from the original on April 29, 2010.

- Parsons, H. Franklin (1891), Report on the Influenza Epidemic of 1889–90, Local Government Board, retrieved June 19, 2013

- Parsons, H. Franklin; Klein, Edward Emmanuel (1893), Further Report and Papers on Epidemic Influenza, 1889–92, Local Government Board, retrieved June 19, 2013

- Valleron, Alain-Jacques; Cori, Anne; Valtat, Sophie; Meurisse, Sofia; Carrat, Fabrice; Boëlle, Pierre-Yves (May 11, 2010). "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". PNAS. 107 (19): 8778–8781. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000886107. PMC 2889325. PMID 20421481. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- Ziegler, Michelle (January 3, 2011). "Epidemiology of the Russian flu, 1889–1890". Contagions: Thoughts on Historic Infectious Disease. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.