Cap-Haïtien: Difference between revisions

Made consistent with main article on the Citadelle, W Hemisphere includes large areas of W Europe & Africa |

→Notable natives: unlinked self-sourced |

||

| (354 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Commune in the department of Nord, Haiti}} |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

| official_name = Cap-Haïtien |

|||

| native_name = {{lang|ht|Kap Ayisyen}} |

|||

| settlement_type = [[List of communes of Haiti|Commune]] |

|||

| image_skyline = View of Cap-Haitien.jpg |

|||

| nicknames = Le Paris des Antilles<br />''The Paris of the Antilles'' |

|||

| map_caption = Location in [[Nord Department (Haiti)|Nord]], [[Haiti]] |

|||

| image_skyline = View of Cap-Haitien.jpg |

|||

| pushpin_map=Haiti |

|||

| image_caption = Skyline of Cap-Haïtien |

|||

| pushpin_label_position=bottom |

|||

| pushpin_map = Haiti <!-- the name of a location map as per http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Location_map --> |

|||

| coordinates_region = HT |

|||

| pushpin_relief = |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[Country]] |

|||

| pushpin_label_position = bottom |

|||

| subdivision_name = [[Haiti]] |

|||

| pushpin_map_caption = Location in Haiti |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[Department (country subdivision)|Department]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|19|45|36|N|72|12|00|W|region:HT|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Nord Department (Haiti)|Nord]] |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[Country]] |

|||

|subdivision_type2 = [[Arrondissements of Haiti|Arrondissement]] |

|||

| subdivision_name = [[Haiti]] |

|||

|subdivision_name2 = [[Cap-Haïtien Arrondissement|Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[Department (country subdivision)|Department]] |

|||

| leader_title = [[Mayor]] |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Nord (Haitian department)|Nord]] |

|||

| leader_name = Michel St Croix |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = [[Arrondissements of Haiti|Arrondissement]] |

|||

|population_as_of = 8 August 2005 |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = [[Cap-Haïtien Arrondissement|Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

|population_footnotes = <ref>''Institut Haïtien de Statistique et d'Informatique'' (IHSI)</ref> |

|||

| |

| established_title = Founded |

||

| established_date = 1670 |

|||

| timezone = [[Eastern Standard Time Zone|Eastern]] |

|||

| leader_title = [[Mayor]] |

|||

| utc_offset = -5 |

|||

| leader_name = Jean Renaud |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Eastern Standard Time Zone|Eastern]] |

|||

| elevation_m = 0 |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = -4 |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 53.5 |

|||

|latd=19 |latm=45 |lats= |latNS=N |

|||

| population_as_of = March, 2015 |

|||

|longd=72 |longm=12 |longs= |longEW=W |

|||

| |

| population_total = 274,404 |

||

| population_footnotes = <ref>''Institut Haïtien de Statistique et d'Informatique'' (IHSI)</ref> |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 5129 |

|||

| population_demonym = Capois(e) |

|||

| timezone = [[Eastern Standard Time Zone|Eastern]] |

|||

| utc_offset = -5 |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Eastern Standard Time Zone|Eastern]] |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = -4 |

|||

| website = https://visithaiti.com/destinations/cap-haitien-city-guide/ |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Sister cities |

{{Sister cities |

||

|boxname=Sister cities<ref>[http://www.sister-cities.org/icrc/directory/Caribbean/Haiti/index Sister Cities International<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|boxname=Sister cities<ref>[http://www.sister-cities.org/icrc/directory/Caribbean/Haiti/index Sister Cities International<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080921032749/http://www.sister-cities.org/icrc/directory/Caribbean/Haiti/index |date=September 21, 2008 }}</ref> |

||

|city1=[[Old San Juan, Puerto Rico]] |

|city1=[[Old San Juan, Puerto Rico]] |

||

|country1=Puerto Rico |

|country1=Puerto Rico |

||

|city2=[[Portland, Maine]], |

|city2=[[Portland, Maine]], United States<ref>{{cite web|url=http://portlandmaine.gov/1196/Portlands-Sister-Cities|title=Portland's Sister Cities - Portland, ME|website=portlandmaine.gov}}</ref> |

||

|country2=United States |

|country2=United States |

||

|city3=[[New Orleans, Louisiana]], |

|city3=[[New Orleans, Louisiana]], United States |

||

|country3=United States |

|country3=United States |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Cap-Haïtien''' ({{IPA|fr|kap a.isjɛ̃|lang}}; {{lang-ht|Kap Ayisyen}}; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled '''Cape Haitien''' in English and often locally referred to as {{lang|fr|'''Le Cap'''}}, {{lang|ht|'''Okap'''|link=no}} or {{lang|fr|'''Au Cap'''|link=no}}, is a [[List of communes of Haiti|commune]] of about 274,000 people on the north coast of [[Haiti]] and capital of the [[Departments of Haiti|department]] of [[Nord (Haitian department)|Nord]]. Previously named ''Cap‑Français'' ({{lang-ht|Kap-Fransè|link=no}}; initially ''Cap-François''<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ncDQSIG6mlMC&pg=PA177 |title=Haiti |editor=Clammer, Paul |page=177|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=978-1-84162-415-0|date=2012}}</ref> {{lang-ht|Kap-Franswa|link=no}}) and ''Cap‑Henri'' ({{lang-ht|Kap-Enri|link=no}}) during the rule of [[Henri Christophe|Henri I]], it was historically nicknamed the ''Paris of the Antilles'', because of its wealth and sophistication, expressed through its architecture and artistic life.<ref name="Knight1991">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FEW8MwZawu8C&pg=PA91 |title=Atlantic Port Cities: Economy, Culture, and Society in the Atlantic World, 1650–1850 |last1=Knight |first1=Franklin W. |last2=Liss |first2=Peggy K. |page=91 |date=1991|publisher=Univ. of Tennessee Press |isbn=9780870496578 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ESy9AQAAQBAJ&pg=PA23 |title=Blue Coat or Powdered Wig: Free People of Color in Pre‑revolutionary Saint Domingue |last=King |first=Stewart R. |page=23 |date=2001|publisher=University of Georgia Press |isbn=9780820342351 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uspTNzJ_NoYC&pg=PA257 |title=Music in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Encyclopedic History |last=Kuss |first=Malena |page=254 |date=2007|publisher=University of Texas Press |isbn=9780292784987 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/dominicanrepubli00clam |url-access=registration |title=Dominican Republic & Haiti |last1=Clammer |first1=Paul |last2=Grosberg |first2=Michael |last3=Porup |first3=Jens |page=[https://archive.org/details/dominicanrepubli00clam/page/331 331] |date=2008 |publisher=Lonely Planet |isbn=978-1-74104-292-4 |series=Country Guide Series}}</ref> It was an important city during the colonial period, serving as the capital of the French Colony of [[Saint-Domingue]] from the city's formal foundation in 1711 until 1770 when the capital was moved to [[Port-au-Prince]]. After the Haitian Revolution, it became the capital of the [[Kingdom of Haiti]] under King Henri I until 1820. |

|||

'''Cap-Haïtien''' (''Okap'' or ''Kapayisyen'' in [[Haitian Creole language|Kréyòl]]) is a city of about 190,000 people on the north coast of [[Haiti]]. Previously, named as '''Cap-Français''' and '''Cap-Henri''', it was an important city during the colonial period and was the first capital of the [[Kingdom of Northern Haiti]] under King [[Henri Christophe]]. |

|||

Cap-Haïtien's |

Cap-Haïtien's long history of independent thought was formed in part by its relative distance from Port-au-Prince, the barrier of mountains between it and the southern part of the country, and a history of large African populations. These contributed to making it a legendary incubator of independent movements since slavery times. For instance, from February 5–29, 2004, the city was taken over by militants who opposed the rule of the Haïtian president [[Jean-Bertrand Aristide]]. They eventually created enough political pressure to force him out of office and the country. |

||

Cap-Haïtien is near the historic Haitian town of [[Milot, Haiti|Milot]], which lies {{convert|12|mi|km|order=flip}} to the southwest along a gravel road. Milot was Haiti's first capital under the self-proclaimed King [[Henri Christophe]], who ascended to power in 1807, three years after Haiti had gained independence from France. He renamed Cap‑Français as Cap‑Henri. Milot is the site of his [[Sans-Souci Palace]], wrecked by the 1842 earthquake. The [[Citadelle Laferrière]], a massive stone fortress bristling with cannons, atop a nearby mountain is {{convert|5|mi|km|0|order=flip|spell=in}} away. On clear days, its silhouette is visible from Cap‑Haïtien. |

|||

The central area of the city is located between the Bay of Cap-Haïtien to the east, and nearby mountainsides to the west, which are increasingly dominated by flimsy urban slums. The streets are generally narrow and arranged in grids. As a legacy of the [[United States|U.S.]] occupation of Haïti from 1915–1934, Cap-Haïtien's north-south streets were renamed as single letters (beginning with Rue A, a major avenue), and its east-west streets with numbers. This system breaks down outside of the central city, which is itself dominated by numerous markets, churches, and low-rise apartment buildings (3–4 floors each) constructed primarily before and during the U.S. occupation. Many such buildings have balconies on the upper floors which overlook the narrow streets below, creating an intimate communal atmosphere during the Haitian dinner hours. |

|||

The small [[Cap-Haïtien International Airport]], located on the southeast edge of the city, is served by several small domestic airlines. It was patrolled by [[Chile]]an [[UN]] troops from the "O'Higgins Base" after the [[2010 Haiti earthquake|2010 earthquake]]. Several hundred UN personnel, including nearby units from [[Nepal]] and [[Uruguay]], are assigned to the city during the 2010-2017 United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti ([[MINUSTAH]]). The airport was the only functioning international airport in the country after the closure of the [[Toussaint Louverture International Airport]] in [[Tabarre]] due to gang violence in March 2024. Significant migration from the capital occurred during the [[Haitian crisis (2018–present)|Haitian crisis]], putting strain on infrastructure and on the educational system.<ref name="capital okap">{{Cite news |newspaper=Independent |title=Haiti's former capital seeks to revive its hey-day as gang violence consumes Port-au-Prince |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/portauprince-ap-haiti-john-french-b2531812.html |last=Coto |first=Dnica |date=2024-04-20 }}</ref> |

|||

Cap-Haïtien is the city of the historic Haïtian town of [[Milot]], which lies 12 miles to the southwest along a gravel road. [[Milot]] was Haïti's first site capital under the self-proclaimed King [[Henri Christophe]], who ascended to power in 1807, three years after Haïti had gained independence from [[France]], renaming the city as Cap-Henri. As a result, [[Milot]] hosts the ruins of the [[Sans-Souci Palace]], wrecked by the 1842 earthquake, as well as the [[Citadelle Laferrière]], a massive stone fortress bristling with cannons. The Citadelle is located five miles from [[Milot]], atop a nearby mountain. On clear days, its silhouette is visible from Cap-Haitien. |

|||

The destruction in 2020 of Shada 2<ref>{{Cite news |newspaper=Le Nouvelliste |title=Démolition de Shada 2 au Cap-Haïtien, bastion du gang « Ajivit » |url=https://lenouvelliste.com/article/217515/demolition-de-shada-2-au-cap-haitien-bastion-du-gang-ajivit |last=Maxineau |first=Gérard |date=2020-06-17 }}</ref> (a slum with 1,500 homes in the southern part of the city) was credited with disrupting gang activity in the former capital.<ref name="capital okap" /> |

|||

The small [[Cap-Haitien International Airport]], located on the southeast edge of the city, is currently served by several small domestic airlines, and is patrolled by [[Chile]]an [[UN]] troops. International service to [[Fort Lauderdale, Florida|Ft. Lauderdale]], [[Florida]] is provided by [[Lynx Air International]]. The city hosts several hundred [[UN]] personnel as part of the ongoing United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti ([[MINUSTAH]]). |

|||

==History== |

|||

[[File:Cathedral of Cap-Haitien.jpg|thumb|The well-preserved Cathedral Notre-Dame of Cap‑Haïtien]] |

|||

The island was occupied for thousands of years by cultures of [[indigenous peoples]], who had migrated from present-day Central and South America. In the 16th century, Spanish explorers in the Caribbean began to colonize [[Hispaniola]]. They adopted the native [[Taíno]] name ''Guárico'' for the area that is today known as "Cap‑Haïtien".<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YbgCAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA152 |title=Notes on Haiti: Made During a Residence in that Republic |volume=1 |last=Mackenzie |first=Charles |page=152 |year=1830}}</ref> Due to the introduction of new infectious diseases, as well as poor treatment, the indigenous peoples population rapidly declined. |

|||

On the nearby coast [[Christopher Columbus|Columbus]] founded his first community in the New World, the short-lived [[La Navidad]]. In 1975, researchers found near Cap‑Haïtien another of the first Spanish towns of Hispaniola: Puerto Real was founded in 1503. It was abandoned in 1578, and its ruins were not discovered until late in the twentieth century.<ref>Florida Museum of Natural History, [http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/histarch/puertoReal.htm Puerto Real].</ref> |

|||

[[File:Caphaitien bike.jpg|thumb|A street scene in Cap‑Haïtien]]The French occupied roughly a third of the island of Hispaniola from the Spanish in the early eighteenth century. They established large [[sugar cane]] [[plantations]] on the northern plains and imported tens of thousands of African slaves to work them. Cap‑Français became an important port city of the French colonial period and the colony's main commercial centre.<ref name="Knight1991"/> It served as the capital of the French colony of [[Saint-Domingue]] from the city's formal founding in 1711 until 1770, when the capital was moved to [[Port-au-Prince]] on the west coast of the island. After the slave revolution, this was the first capital of the Kingdom of Haiti under King Henri I, when the nation was split apart. |

|||

The central area of the city is between the Bay of Cap‑Haïtien to the east and nearby mountainsides, as well as the [[Acul Bay]], to the west; these are increasingly dominated by flimsy urban slums. The streets are generally narrow and arranged in grids. As a legacy of the United States' occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934, Cap‑Haïtien's north–south streets were renamed as single letters (beginning with Rue A, a major avenue) and going to "Q", and its east–west streets with numbers from 1 to 26; the system is not followed outside the central city, where French names predominate. The historic city has numerous markets, churches, and low-rise apartment buildings (of three–four storeys), constructed primarily before and during the U.S. occupation. Much of the infrastructure is in need of repair. Many such buildings have balconies on the upper floors, which overlook the narrow streets below. With people eating outside on the balconies, there is an intimate communal atmosphere during dinner hours. |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

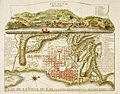

File:Cap_Français_-_Gravure_ancienne_-_1728.jpg|Engraving of [[Cap-Français]] in 1728 |

|||

File:Vue_de_l%27incendie_de_la_ville_du_cap_français_f1.highres.jpg|Fire of [[Cap Français]], 21 June 1793 |

|||

File:Prise du Cap Français par l'Armée Française, sous le Commandement du Général Leclerc, le 15 et 20 Pluviose, An 10 (4-9 Février 1802) - détail.jpg|The French army led by Le Clerc lands in [[Cap Français]] (1802) |

|||

File:American Marines In 1915 defending the entrance gate in Cap-Haitian - 34510.jpg|American Marines in 1915 defending the entrance gate in Cap-Haïten |

|||

File:Marines' base in Cap-Haïtien.jpg|Marine's base at Cap-Haïtien |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Economy== |

==Economy== |

||

[[File:Street view in Cap Haitien, Haiti.jpg|thumb|left|French colonial architecture in Cap]] |

|||

Cap-Haïtien is known as the nation's largest center of Historic monuments and Tourism Finance. from its calm water and picturesque [[Caribbean]] beaches, to its Citadelle Laferiere one of the Great Wonders of the World have made it a resort and vacation destination for Haïti's upper classes, comparable to [[Pétionville]]. Cap-Haïtien has, in general, also seen greater foreign tourist activity than much of Haiti, due to its isolation from political instability. Cap-Haïtien is also unique for its French colonial architecture, which has been uniquely well preserved. After the [[Haitian Revolution]], many craftsmen from Cap-Haïtien fled to French-controlled [[New Orleans]], as a result, the two cities share many similarities in styles of architecture. Especially notable are the many [[gingerbread house]]s lining the city's older streets. |

|||

[[Image:Cathedral of Cap-Haitien.jpg|thumb|200px|The well-preserved Cathedral Notre-Dame of Cap-Haitien.]] |

|||

Cap-Haïtien is known as the nation's largest center of historic monuments and as such, it is a tourist destination. The bay, beaches and monuments have made it a resort and vacation destination for Haiti's upper classes, comparable to [[Pétion-Ville]]. Cap‑Haïtien has also attracted more international tourists at times, as it has been isolated from the political instability in the south of the island. |

|||

==Labadie== |

|||

The walled [[Labadee|Labadie]] beach resort compound is located six miles to the city's northwest, and has served as a brief stopover for [[Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd.|Royal Caribbean]] cruise ships. Today, major Royal Caribbean Cruise ships, including the largest and most luxurious ([[Oasis of the Seas]]), dock weekly at Labadie. It is a private resort leased by Royal Caribbean International. Royal Caribbean International has contributed the largest proportion of tourist revenue to Haiti since 1986, employing 300 locals, allowing another 200 to sell their wares on the premises, and paying the Haitian government US$6 per tourist. The resort is connected to Cap-Haïtien by a mountainous dirt and gravel road. RCI has built a pier at Labadie capable of servicing the Oasis class ships, completed in late 2009, no longer requiring passengers to be tendered from anchored ships.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.expedia.com/daily/cruise/geo/ports.asp?tiid=6024010 |

|||

|title=Labadie |

|||

|publisher=Expedia.com |

|||

|accessdate=2007-08-02 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Attractions include a Haitian [[flea market]], numerous [[beach]]es, [[watersport]]s, a water-oriented playground, and the popular [[zip-line]].<ref>{{cite news |

|||

|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/19/AR2007011900555.html |

|||

|title=Labadie |

|||

|publisher=The Washington Post |

|||

|accessdate=2007-08-02 |

|||

| date=2007-01-21 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

It has a wealth of French colonial architecture, which has been well preserved. During and after the [[Haitian Revolution]], many craftsmen from Cap‑Haïtien, who were [[free people of color]], fled to French-controlled [[New Orleans]] as they were under attack by the mostly African slaves. As a result, the two cities share many similarities in styles of architecture. Especially notable are the [[gingerbread house (architecture)|gingerbread house]]s lining the city's older streets.{{cn|date=April 2024}} |

|||

==Vertières== |

|||

Vertières is the site of the [[Battle of Vertières]] - the last and defining battle of the [[Haitian Revolution]]. On November 18, 1803, Haitian rebels led by [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] defeated a French colonial army led by the [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau|Comte de Rochambeau]], leading to the independence of Haïti. |

|||

It is also the site that made Capois La Mort famous for his bravery. In the last battle for the Independence he survived all the French bullets that nearly killed him; his horse was killed underhim and his hat fell off but he kept on marching on the French while screaming "En avant!" which means "Let's go forward". As a result, the independent Republic of Haiti was proclaimed on 1 January 1804. 18 November has been widely celebrated since then as a Day of Army and Victory in Haiti. |

|||

Since 2021, there have been significant electrical outages in Cap Haïtien, due in large part to a lack of fuel. Those who can afford it have invested in solar energy.<ref>{{cite news |last=peralta |first=Eyder |work=NPR |date=2024-04-18 |title=A portrait of Haitians trying to survive without a government |url=https://www.npr.org/2024/04/18/1245048299/haiti-haitians-cap-haitien }}</ref><ref name="6monthsinDark">{{cite news| newspaper=Ayibo Post | author=Jameson Francisque |date=2022-06-09 |title=La ville du Cap-Haitien plongée dans le noir depuis six mois |url=https://ayibopost.com/la-ville-du-cap-haitien-plongee-dans-le-noir-depuis-six-mois/ }}</ref> A power plant built in [[Caracol, Haiti#Construction|Caracol]] to provide electricity to the Industrial Park reaches as far as [[Limonade]] 30 minutes from downtown Cap Haïtien.<ref name="6monthsinDark" /> |

|||

[[Image:Citadelle Laferrière.jpg|thumb|200px|View of the Citadelle Laferrière, in northern Haiti]] |

|||

==Tourism== |

|||

==Citadelle Laferrière== |

|||

===Labadie and other beaches=== |

|||

The [[Citadelle Laferrière]] or, Citadelle Henri Christophe, or simply the Citadelle, is a large mountaintop [[fortress]] located approximately {{convert|17|mi|km}} south of the city of Cap-Haïtien and five miles (8 km) beyond the town of [[Milot]]. It is the largest fortress in the Americas and was listed by UNESCO as a [[World Heritage Site]] in 1982—along with the nearby [[Sans-Souci Palace]]. The Citadel was built by [[Henri Christophe]], a leader during the Haitian slave rebellion and subsequently King of Northern Haiti, after the country gained its independence from France at the beginning of the 19th century. |

|||

[[File:Labadee, Haiti Aug 2002.JPG|thumb|left|Labadie beach and village]] |

|||

The walled [[Labadee|Labadie]] (or Labadee) beach resort compound is located {{convert|6|mi|km|0|order=flip|spell=in}} to the city's northwest. It serves as a brief stopover for [[Royal Caribbean International]] (RCI) cruise ships. Major RCI cruise ships dock weekly at Labadie. It is a private resort leased by RCI, which has generated the largest proportion of tourist revenue to Haiti since 1986. It employs 300 locals, allows another 200 to sell their wares on the premises, and pays the Haitian government US$6 per tourist. |

|||

==2010 Haiti Earthquake== |

|||

In the wake of the [[2010 Haiti earthquake]] which destroyed port facilities in Port-au-Prince, Cap-Haïtien's [[container port]] was being used to deliver relief supplies <ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/17/world/americas/17haiti.html Officials Strain to Distribute Aid to Haiti as Violence Rises]</ref>. |

|||

The resort is connected to Cap‑Haïtien by a mountainous, recently paved road. RCI has built a pier at Labadie, completed in late 2009, capable of servicing the luxury-class large ships.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.expedia.com/daily/cruise/geo/ports.asp?tiid=6024010 |title=Labadie |publisher=Expedia.com |access-date=2007-08-02 }}</ref> |

|||

Since the city in general was not as affected in is infrastructure as Port-au-Prince, former Port-au-Prince businessmen and many people have moved to Cap Haitian. |

|||

Attractions include a Haitian market, numerous beaches, watersports, a water-oriented playground, and a [[zip-line]].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/19/AR2007011900555.html |title=Labadie |newspaper=The Washington Post |access-date=2007-08-02 |date=2007-01-21 }}</ref> |

|||

Few damages have been reported as consequence of the 2010 earthquake, such as the collapse of a school classroom that killed 4 children and injured 1. |

|||

[[File:Watertaxis at Labadie beach Haiti.jpg|thumb|Water taxis parked at Labadie beach]] |

|||

[[File:Paradis beach in Haiti.jpg|thumb|A view of the beach at Paradis]] |

|||

Cormier Plage is another beach on the way to Labadie, and there are also water taxis from Labadie to other beaches, like Paradis beach. In addition, Belli Beach is a small sandy cove with boats and hotels. Labadie village can be visited from here.<ref name="Cameron, p. 406">Cameron, p. 406</ref> |

|||

==Higher education== |

|||

A union of 4 Congregational Church Private Schools have been Present for Two decades in Cap-Haitien. They are considered as higher education establishment the mainstream framework of the Public school system. also known as École Normale Supérieure outside, The term is most commonly used to refer of [[Academic]] [[Excellence]], Selectivity in [[University and college admissions|Admissions]], and [[Social]] [[Elitism]]. |

|||

===Vertières=== |

|||

*College Notre-Dame du Perpetuels Secours des Peres de Sainte-Croix |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=April 2024}} |

|||

*Ecole des Freres De L'instruction Chretienne |

|||

*Ecole Saint Joseph De Cluny des Soeurs Anne-Marie Javoue |

|||

Vertières is the site of the [[Battle of Vertières]], the last and defining battle of the [[Haitian Revolution]]. On November 18, 1803, the Haitian army led by [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] defeated a French colonial army led by the [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau|Comte de Rochambeau]]. The French withdrew their remaining 7,000 troops (many had died from yellow fever and other diseases), and in 1804, Dessalines' revolutionary government declared the independence of Haiti. The revolution had been underway, with some pauses, since the 1790s. |

|||

*College Regina Assumpta des Soeurs de Sainte-Croix |

|||

In this last battle for independence, rebel leader Capois La Mort survived all the French bullets that nearly killed him. His horse was killed under him, and his hat fell off, but he kept advancing on the French, yelling, "En avant!" (Go forward!) to his men. He has become renowned as a hero of the revolution. The 18 of November has been widely celebrated since then as a Day of Army and Victory in Haiti. |

|||

*college Martin Luther King |

|||

*College Pratique du Nord |

|||

[[File:Citadelle Laferrière.jpg|thumb|View of the Citadelle Laferrière, in northern Haiti]] |

|||

[[File:Sans Souci Palace Ruins.jpg|thumb|Inside the ruins of [[Sans Souci Palace]]]] |

|||

===Citadelle Henry and Sans-Souci Palace=== |

|||

The [[Citadelle Laferrière]], also known as Citadelle Henry, or the Citadelle, is a large mountaintop [[fortress]] located approximately {{convert|17|mi|km|order=flip}} south of the city of Cap‑Haïtien and {{convert|5|mi|km|order=flip|0|spell=in}} beyond the town of [[Milot, Haiti|Milot]]. It is the largest fortress in the Americas, and was listed by UNESCO as a [[World Heritage Site]] in 1982 along with the nearby [[Sans-Souci Palace]]. The Citadel was built by [[Henry Christophe]], a leader during the Haitian slave rebellion and self-declared King of Northern Haiti, after the country gained its independence from France in 1804. Together with the remains of his [[Sans-Souci Palace]], damaged in the 1842 earthquake, Citadelle Henry has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.<ref>[https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/180 "Citadelle Henry"], UNESCO World Heritage Sites</ref> |

|||

===Bois Caïman=== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Further|Bois Caïman}} |

|||

[[Bois Caïman]] ({{lang-ht|Bwa Kayiman}}), {{convert|3|km|mi|0|spell=in}} south of road RN 1, is the place where [[Haitian Vodou|Vodou]] rites were performed under a tree at the beginning of the slave revolution. For decades, [[Maroon (people)|maroons]] had been terrorizing slaveholders on the northern plains by poisoning their food and water. Makandal is the legendary (and perhaps historical) figure associated with the growing resistance movement. By the 1750s, he had organized the maroons, as well as many people enslaved on plantations, into a secret army. Makandal was murdered (or disappeared) in 1758, but the resistance movement grew. |

|||

At Bois Caïman, a maroon leader named [[Dutty Boukman]] held the first mass antislavery meeting secretly on August 14, 1791. At this meeting, a Vodou ceremony was performed, and all those present swore to die rather than to endure the continuation of slavery on the island. Following the ritual led by Boukman and a [[Mambo (Vodou)|mambo]] named [[Cécile Fatiman]], the insurrection started on the night of August 22–23, 1791. Boukman was killed in an ambush soon after the revolution began. Jean-François was the next leader to follow Dutty Boukman in the uprising of the slaves, the Haitian equivalent of the [[storming of the Bastille]] in the French Revolution. Slaves burned the plantations and cane fields, and massacred French colonists across the northern plains. They also attacked Cap-Français and some of the free people of color. Eventually the revolution gained the independence of Haiti from France and freedom for the slaves. The site of Dutty Boukman's ceremony is marked by a [[ficus]] tree. Adjoining it is a colonial well, which is credited with mystic powers. |

|||

===Morne Rouge=== |

|||

Morne Rouge is {{convert|8|km|mi|0|spell=in}} to the south of Cap. It is the site of the sugar plantation known as "Habitation Le Normand de Mezy", known for several slaves who led the rebellion against the French.<ref name="Cameron, p. 409">Cameron, p. 409</ref> |

|||

==Disasters== |

|||

===1842 Cap-Haïtien earthquake=== |

|||

{{Main|1842 Cap-Haïtien earthquake}} |

|||

On 7 May 1842, an [[list of earthquakes in Haiti|earthquake]] destroyed most of the city and other towns in the north of Haiti and the neighboring Dominican Republic. Among the buildings destroyed or significantly damaged was the [[Sans-Souci Palace]]. Ten thousand people were killed in the [[earthquake]].<ref>{{Citation |last=Prepetit |first=Claude |title=Tremblements de terre en Haïti, mythe ou réalité ? |date=9 October 2008 |url=http://www.bme.gouv.ht/risques%20geologiques/LeMatin_s%E9ismes.pdf |work=Le Matin |volume=33082}}{{dead link|date=July 2017|bot=InternetArchiveBot|fix-attempted=yes}}, quoting {{Citation |last=Moreau de Saint-Méry |first=Médéric Louis Élie |title=Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'Ile Saint Domingue |author-link=Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry}} and {{Citation |author=J. M. Jan, bishop of Cap-Haïtien |title=Documentation religieuse |year=1972 |publisher=Éditions Henri Deschamps}}. {{cite web |title=Cap-Haitian Earthquake of May 7, 1842 |url=http://haitimega.com/Cap_Haitien-Cap_Haitian_Earthquake_of_May_7_1842/84144788150681600/article_84481504601309194.jsp |url-status=usurped |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111221113349/http://haitimega.com/Cap_Haitien-Cap_Haitian_Earthquake_of_May_7_1842/84144788150681600/article_84481504601309194.jsp |archive-date=2011-12-21 |access-date=2011-09-28}}</ref> Its magnitude is estimated as 8.1 on the Richter scale. |

|||

===2010 Haiti earthquake=== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Main|2010 Haiti earthquake}} |

|||

In the wake of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which destroyed port facilities in Port-au-Prince, the [[Port international du Cap-Haïtien]] was used to deliver relief supplies by ship.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/17/world/americas/17haiti.html?pagewanted=all|title=Officials Strain to Distribute Aid to Haiti as Violence Rises - NYTimes.com|first1=Ginger|last1=Thompson|first2=Damien|last2=Cave|newspaper=The New York Times|date=16 January 2010}}</ref> |

|||

As the city's infrastructure suffered little damage, numerous businessmen and many residents have moved here from Port-au-Prince. The airport is patrolled by [[Chile]]an [[UN]] troops since the 2010 earthquake, and several hundred UN personnel have been assigned to the city as part of the ongoing United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti ([[MINUSTAH]]). They are working on recovery throughout the island. |

|||

After the earthquake, the port of [[Labadee]] was demolished and the pier enlarged and completely re-paved with concrete, which now allows larger cruise ships to dock, rather than [[tendering]] passengers to shore. |

|||

===Cap-Haïtien fuel tanker explosion=== |

|||

{{Main|Cap-Haïtien fuel tanker explosion}} |

|||

On 14 December 2021, over 75 people were killed when a fuel [[tank truck]] overturned and later exploded in the Samari neighborhood of Cap-Haïtien. |

|||

==Transportation== |

|||

===Airports=== |

|||

Cap-Haïtien is served by the [[Cap-Haïtien International Airport|Cap-Haïtien International Airport (CAP)]], Haiti's second busiest airport.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://bigstory.ap.org/article/haiti-renames-airport-hugo-chavez |title=Haiti renames airport for Hugo Chavez |work=The Big Story |access-date=6 June 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715232736/http://bigstory.ap.org/article/haiti-renames-airport-hugo-chavez |archive-date=15 July 2015 }}</ref> It was a hub for [[Salsa d'Haiti]] prior to its cessation in 2013. [[American Airlines]] operated international flights to CAP for a number of years, but canceled their last connection in July, 2020, after the [[COVID-19 pandemic]] significantly reduced passenger demand. American Airlines was the last major US flight operator to provide service to CAP and thereby Northern Haiti—in July, 2020, Cap-Haïtien became only accessible by air travel through limited flights from [[Port-au-Prince|Port-au-Prince's]] [[Toussaint Louverture International Airport]].<ref>{{Cite news|last=Charles|first=Jacqueline|date=July 1, 2020|title=American Airlines reduces service to Haiti, cancels Miami-Cap-Haïtien route|work=Miami Herald|url=https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/haiti/article243930267.html}}</ref> [[Spirit Airlines]], which had previously canceled their service due to political unrest and low demand in 2019, announced in October, 2020 that they would resume limited service to CAP in December of the same year.<ref>{{Cite press release|last=Inc|first=Spirit Airlines|date=2020-10-01|title=Spirit Airlines to Restore Flights to Cap-Haitien, Re-Activate Region's Only Nonstop Service to U.S.|url=http://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/10/01/2102488/0/en/Spirit-Airlines-to-Restore-Flights-to-Cap-Haitien-Re-Activate-Region-s-Only-Nonstop-Service-to-U-S.html|access-date=2020-11-19|website=GlobeNewswire News Room}}</ref> |

|||

===Seaport=== |

|||

The [[Port international du Cap-Haïtien]] is Cap-Haïtien's main [[seaport]]. [[USAID]] financed $24 million of works to renovate the port beginning in May 2024.<ref>{{cite news |last=Sénat |first=Jean Daniel |newspaper=Le Nouvelliste |date=2024-04-12 |url=https://lenouvelliste.com/article/247665/vers-la-rehabilitation-du-port-international-du-cap-haitien |title=Vers la réhabilitation du port international du Cap-Haïtien |lang=fr }}</ref> |

|||

===Roads=== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=April 2024}} |

|||

The [[Route Nationale#1]] connects Cap-Haïtien with the Haitian capital city Port-au-Prince via the cities of [[Saint-Marc]] and [[Gonaïves]]. |

|||

The [[Route Nationale#3]] also connects Cap-Haïtien with Port-au-Prince via the [[Central Plateau (Haiti)|Central Plateau]] and the cities of [[Mirebalais]] and [[Hinche]]. |

|||

Cap-Haïtien has one of the best grid systems in Haiti with its north–south streets were renamed as single letters (beginning with Rue A, a major avenue), and its east–west streets with numbers. |

|||

The [[Boulevard du Cap-Haitian]] (also called the Boulevard Carenage) is Cap‑Haïtien's main [[boulevard]] that runs along the Atlantic Ocean in the northern part of the city. |

|||

===Public transportation=== |

|||

Cap-Haïtien is served by [[tap tap]] and local taxis or motorcycles. |

|||

==Health== |

|||

Cap Haitien is served by the teaching hospital: [[Hôpital Universitaire Justinien]]. |

|||

==Education== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=April 2024}} |

|||

A union of four Catholic Church private schools have been present for two decades in Cap‑Haïtien. They have higher-level grades, equivalent to the lycées that feed the Écoles Normale Supérieure in France. They have high standards of academic excellence, selectivity in [[University and college admissions|admissions]], and generally their students come from the social and economic elite. Also, the lyceé Philippe Guerrier that was built in 1844 by the Haitian President, Philippe Guerrier, has been a fountain of knowledge for more than a century. |

|||

* Collège Notre-Dame du Perpetuel Secours des Pères de Sainte-Croix |

|||

* Collège Regina Assumpta des Sœurs de Sainte-Croix |

|||

* École des Frères de l'instruction Chrétienne |

|||

* École Saint Joseph de Cluny des Sœurs Anne-Marie Javoue |

|||

* Lyceé Philippe Guerrier built by the Haitian President, Philippe Guerrier in 1844. |

|||

===Universities=== |

|||

Cap Haitien is home to the Cap-Haitien Faculty of Law, Economics and, Management; the Public University of the North in Cap Haitien (UPNCH). The new [[Université Roi Henry Christophe]] is nearby in [[Limonade]]. |

|||

==Sport== |

|||

Cap Haitien has the [[Parc Saint-Victor]] home of three major league teams: [[Football Inter Club Association]], [[AS Capoise]], and [[Real du Cap]]. |

|||

== Communal sections == |

|||

The commune consists of three [[communal section]]s, namely: |

|||

* [[Bande du Nord]], urban (part of the commune of Cap-Haïtien) and rural |

|||

* [[Haut du Cap]], urban (part of the commune of Cap-Haïtien) and rural |

|||

* [[Petit Anse (communal section)|Petit Anse]], urban (commune of Petit Anse) and rural |

|||

==Notable natives== |

==Notable natives== |

||

* [[Pierre Nord Alexis]] (1820 – 1910), [[List of heads of state of Haiti|President of Haiti]], 1902–1908. |

|||

[[Tyrone Edmond]], Haitian-born model. |

|||

* [[Tancrède Auguste]] (1856 – 1913), the 20th [[List of heads of state of Haiti|President of Haiti]], 1912–1913. |

|||

* [[Étienne Chavannes]] (born 1939), a Haitian painter of crowd scenes |

|||

* [[Tyrone Edmond]], Haitian-born model. |

|||

* [[Arly Larivière]], Haitian [[Kompa]] musician and composer |

|||

* [[Yolette Lévy]] (1938–2018), Haitian-born Canadian politician and activist |

|||

* [[Lewis Page Mercier]] (1820–1875), Haitian educator and educator |

|||

* [[Alfred Auguste Nemours]] (1883–1955), military historian and diplomat |

|||

* [[Philomé Obin]] (1892–1986), artist and painter |

|||

* [[Leonel Saint-Preux]] (born 1985), footballer, played 41 games for [[Haiti national football team|Haiti]] |

|||

* [[Bruny Surin]] (born 1967), track and field runner, Olympic medalist, lives in Canada |

|||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<center> |

<gallery class="center"> |

||

File:Sans-Souci Palace front.jpg|Front view of [[Sans-Souci Palace]] |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:Cap-Haitiens city council.jpg|''Hotel de Ville'' (City Hall), site of the City Council, Cap-Haïtien. |

|||

Image:Sans-Souci Palace front.jpg|Front view of Sans-Souci Palace |

|||

File:Cruise ship Labadee Haïti.jpg|A cruise ship at Labadie. |

|||

Image:Cap-Haitiens city council.jpg|Cap Haitien's City Council. (Not a hotel) |

|||

Image:Cruise ship Labadee Haïti.jpg|A Cruise ship at Labadee. |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

</center> |

|||

==Television== |

==Television== |

||

{{Div col| |

{{Div col|colwidth=22em}} |

||

*Télé Vénus |

* Télé Vénus Ch 5 |

||

*Télé Paradis <ref> |

* Télé Paradis Ch 16<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radioteleparadis.com/|title=Radio Tele Pardadis|website=www.radioteleparadis.com}}</ref> |

||

*Chaîne 6 |

* Chaîne 6 |

||

*Chaîne 7 |

* Chaîne 7 |

||

*Chaîne 11 |

* Chaîne 11 |

||

* |

* Télé Capoise Ch 8 |

||

* |

* Télé Africa Ch 12<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.radioteleafrica.com/ |title=Home |website=radioteleafrica.com}}</ref> |

||

* HMTV Ch 20 |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

* Télé Union Ch 22 |

|||

* Télé Apocalypse Ch 24 |

|||

* Télévision Nationale d'Haiti Ch 4<ref>[http://www.tnh.ht/ Index of /<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150217153602/http://www.tnh.ht/ |date=February 17, 2015 }}</ref> |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

== |

==Radio stations== |

||

{{Div col| |

{{Div col|colwidth=22em}} |

||

* [[Bon Déjeuner! Radio (Haiti)|Bon Déjeuner! Radio]], an internet radio station in [[Haiti]], broadcasting from [[Cap-Haitien]]. |

|||

*Radyo Atlantik, 92.5 FM <ref>www.atlantikhaiti.com</ref> |

|||

* Radyo Atlantik, 92.5 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.atlantikhaiti.com|title=AtLanTikHaiti.com|website=www.atlantikhaiti.com}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio 4VEH (4VEF), 840 AM <ref>[http://www.radio4veh.org/ Radio 4VEH, La Voix Évangélique d’Haïti<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

* Radio 4VEH (4VEF), 840 AM <ref name="radio4veh.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.radio4veh.org/|title=Radio 4VEH - La Voix Évangélique d'Haïti|website=www.radio4veh.org|access-date=2008-06-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080515210614/http://www.radio4veh.org/|archive-date=2008-05-15|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio 4VEH, 94.7 FM <ref>http://www.radio4veh.org/</ref> |

|||

* Radio 4VEH, 94.7 FM <ref name="radio4veh.org"/> |

|||

*Radio 7 FM, 92.7 <ref>[http://www.tele7.com/ Tele7 - Inicio<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

* Radio 7 FM, 92.7 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tele7.com/|title=Tele7 - Portada|website=www.tele7.com}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio Cap-Haïtien |

|||

*Radio |

* Radio Cap-Haïtien |

||

*Radio |

* Radio Citadelle, 91.1 FM |

||

* Radio Étincelle |

|||

*Radio Gamma, 99.7 (Based in Fort Liberté) <ref>[http://www.gammafm.com/ Radio Gamma fm, 99.7 Mhz - Bienvenue<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*Radio |

* Radio Gamma, 99.7 (based in Fort-Liberté) <ref>[http://www.gammafm.com/ Radio Gamma fm, 99.7 MHz - Bienvenue<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081204115539/http://www.gammafm.com/ |date=December 4, 2008 }}</ref> |

||

* [[Radio Lumiere|Radio Lumière]], 98.1 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radiolumiere.org/|title=Radio Lumiere - Home|website=www.radiolumiere.org}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio Méga,103.7 FM |

|||

*Radio |

* Radio Méga, 103.7 FM |

||

* Radio Sans-Souci FM, 106.9 FM |

|||

*Radio VASCO, 93.7 FM <ref>[http://radiovascofmhaiti.com/ Homestead | Build, Make & Create Your Own Website – FREE! Website Hosting & Website Building Software<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

* Radio VASCO, 93.7 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://radiovascofmhaiti.com/|title=Radio Vasco|access-date=2008-06-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080517015953/http://radiovascofmhaiti.com/|archive-date=2008-05-17|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio Vénus FM |

|||

* Radio Vénus FM, 104.3 FM |

|||

*Sans Souci FM, 106.9 <ref>[http://www.radiosanssouci.com/ Sans Souci FM<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

* Sans Souci FM, 106.9 <ref>[http://www.radiosanssouci.com/ Sans Souci FM<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080619123800/http://www.radiosanssouci.com/ |date=2008-06-19 }}</ref> |

|||

*Voix de l’Ave Maria |

|||

*Voix |

* Voix de l'Ave Maria, 98.5 FM |

||

* Voix du Nord, 90.3 FM |

|||

*Radio Paradis <ref>http://www.radioteleparadis.com</ref> |

|||

*Radio |

* Radio Intermix, 93.1 FM: La Reference Radio en Haïti # 1 |

||

* Radio Paradis <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radioteleparadis.com|title=Radio Tele Pardadis|website=www.radioteleparadis.com}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio Hispaniola |

|||

* Radio Nirvana, 97.3 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radionirvanafm.com|title=Welcome radionirvanafm.com - BlueHost.com|website=www.radionirvanafm.com}}</ref> |

|||

*Radio Passion Haïti <ref>[http://www.radiopassionhaiti.com/ Radio Passion Haiti :: Sport Haiti, Actualités Haiti, Économie Haiti, Santé Haiti, Météo Haiti, Politique Haiti, Culture Haiti<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

* Radio Hispaniola |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

* Radio Maxima, 98.1.FM <ref>[http://www.radiomaximahaiti.com/<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{Cite web |url=http://www.radiomaximahaiti.com/ |title=Radio Maxima 98.1 Fm |access-date=January 15, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140116131946/http://www.radiomaximahaiti.com/ |archive-date=January 16, 2014 |url-status=bot: unknown |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

* Radio Voix de l'ile, 94.5 FM <ref>[http://www.rvihaiti.com/<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{Cite web |url=http://www.rvihaiti.com/ |title=Lavpoix de l'ile |access-date=January 15, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140116114902/http://www.rvihaiti.com/ |archive-date=January 16, 2014 |url-status=bot: unknown |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

* Radio Digital, 101.3 FM <ref>{{cite web|url=http://radioteledigital.fr.ht/%3C!--|title=Radio Tele Digital 101.3 FM Haiti, Musique, Actualites, Interview, Infos, Foot-ball, Education, Culture|first=Jackendy R.|last=Noel|website=radioteledigital.fr.ht}}</ref> |

|||

* Radio Oxygene, 103.3 FM <ref>[http://www.oxygenecaphaitien.com//<!-- Bot generated title -->] {{Cite web |url=http://www.oxygenecaphaitien.com/ |title=Radio Oxygene Cap-Haitien - ACCEUIL |access-date=January 15, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140125082933/http://www.oxygenecaphaitien.com/ |archive-date=January 25, 2014 |url-status=bot: unknown |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

* Radio Passion, 101.7 FM Haïti <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radiopassionhaiti.com/|title=Radio Passion Haiti :: Sport Haiti, Actualités Haiti, Économie Haiti, Santé Haiti, Météo Haiti, Politique Haiti, Culture Haiti<!-- Bot generated title -->}}</ref> |

|||

* Radio City Inter Haïti |

|||

* La Radio de l'éducation |

|||

* Radio Multivers FM Cap haitien |

|||

* Toujours plus hauts |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Battle of Cap-Français]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{reflist|30em}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

* Dubois, Laurent [http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/648922902 Haiti : the aftershocks of history]. New York : Metropolitan Books, 2012. |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

* Popkin, Jeremy D. [http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/123284761 ''Facing racial revolution : eyewitness accounts of the Haitian Insurrection''] Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2007. |

|||

* Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall. [http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/754733419 Haitian history : new perspectives.] New York : Routledge, 2012. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{ |

{{commons category|Cap-Haitien}} |

||

* {{wikivoyage inline|Cap-Haïtien}} |

|||

*[http://www.caphaitien.info Cap Haitien Haiti] |

|||

*[http://www.bartleby.com/65/ca/CapHaiti.html short article] - Columbia encyclopedia |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20000817164556/http://www.bartleby.com/65/ca/CapHaiti.html short article] - Columbia encyclopedia |

||

* [http://thelouvertureproject.org/wiki |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20080821111613/http://thelouvertureproject.org/wiki The Louverture Project]: [https://web.archive.org/web/20060717231918/http://www.thelouvertureproject.org/wiki/index.php?title=Le_Cap Cap Haïtien] - Article from Haitian history wiki. |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120122033548/http://konbitsante.org/cap-haitien-haiti Konbit Sante's page on Cap-Haitien. Konbit Sante is a non-denominational mixed NGO.] |

|||

{{coord|19|45|N|72|12|W|region:HT_type:city|display=title}} |

|||

{{Communes of Haiti}} |

{{Communes of Haiti}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

* http://ramoolive.blogspot.com/ |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cap-Haitien}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cap-Haitien}} |

||

[[Category:Populated places in Haiti]] |

|||

[[Category:Nord Department]] |

|||

[[Category:Communes of Haiti]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Cap-Haïtien| ]] |

||

[[Category:1711 establishments in the French colonial empire]] |

|||

[[da:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[Category:Communes of Haiti]] |

|||

[[de:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[Category:Populated places in Nord (Haitian department)]] |

|||

[[et:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[Category:Port cities in the Caribbean]] |

|||

[[es:Cabo Haitiano]] |

|||

[[eo:Haitia Kabo]] |

|||

[[fa:کاپ-هائیتین]] |

|||

[[fr:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[hr:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[id:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[it:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[ht:Kap Ayisyen (komin)]] |

|||

[[nl:Cap-Haïtien (stad)]] |

|||

[[ja:カパイシャン]] |

|||

[[no:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[nn:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[pl:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[pt:Cabo Haitiano]] |

|||

[[ru:Кап-Аитьен]] |

|||

[[simple:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[fi:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[sv:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[uk:Кап-Аїтьєн]] |

|||

[[war:Cap-Haïtien]] |

|||

[[zh:海地角]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 13:49, 3 September 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Cap-Haïtien

Kap Ayisyen | |

|---|---|

Skyline of Cap-Haïtien | |

| Nicknames: Le Paris des Antilles The Paris of the Antilles | |

| Coordinates: 19°45′36″N 72°12′00″W / 19.76000°N 72.20000°W | |

| Land | Haiti |

| Department | Nord |

| Arrondissement | Cap-Haïtien |

| Gegründet | 1670 |

| Regierung | |

| • Mayor | Jean Renaud |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53.5 km2 (20.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (March, 2015)[1] | |

| • Total | 274,404 |

| • Density | 5,129/km2 (13,280/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Capois(e) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| Website | https://visithaiti.com/destinations/cap-haitien-city-guide/ |

| Sister cities[2] |

|---|

|

Cap-Haïtien (French: [kap a.isjɛ̃]; Haitian Creole: Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as Le Cap, Okap oder Au Cap, is a commune of about 274,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previously named Cap‑Français (Haitian Creole: Kap-Fransè; initially Cap-François[4] Haitian Creole: Kap-Franswa) and Cap‑Henri (Haitian Creole: Kap-Enri) during the rule of Henri I, it was historically nicknamed the Paris of the Antilles, because of its wealth and sophistication, expressed through its architecture and artistic life.[5][6][7][8] It was an important city during the colonial period, serving as the capital of the French Colony of Saint-Domingue from the city's formal foundation in 1711 until 1770 when the capital was moved to Port-au-Prince. After the Haitian Revolution, it became the capital of the Kingdom of Haiti under King Henri I until 1820.

Cap-Haïtien's long history of independent thought was formed in part by its relative distance from Port-au-Prince, the barrier of mountains between it and the southern part of the country, and a history of large African populations. These contributed to making it a legendary incubator of independent movements since slavery times. For instance, from February 5–29, 2004, the city was taken over by militants who opposed the rule of the Haïtian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. They eventually created enough political pressure to force him out of office and the country.

Cap-Haïtien is near the historic Haitian town of Milot, which lies 19 kilometres (12 mi) to the southwest along a gravel road. Milot was Haiti's first capital under the self-proclaimed King Henri Christophe, who ascended to power in 1807, three years after Haiti had gained independence from France. He renamed Cap‑Français as Cap‑Henri. Milot is the site of his Sans-Souci Palace, wrecked by the 1842 earthquake. The Citadelle Laferrière, a massive stone fortress bristling with cannons, atop a nearby mountain is eight kilometres (5 mi) away. On clear days, its silhouette is visible from Cap‑Haïtien.

The small Cap-Haïtien International Airport, located on the southeast edge of the city, is served by several small domestic airlines. It was patrolled by Chilean UN troops from the "O'Higgins Base" after the 2010 earthquake. Several hundred UN personnel, including nearby units from Nepal and Uruguay, are assigned to the city during the 2010-2017 United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). The airport was the only functioning international airport in the country after the closure of the Toussaint Louverture International Airport in Tabarre due to gang violence in March 2024. Significant migration from the capital occurred during the Haitian crisis, putting strain on infrastructure and on the educational system.[9]

The destruction in 2020 of Shada 2[10] (a slum with 1,500 homes in the southern part of the city) was credited with disrupting gang activity in the former capital.[9]

History

[edit]

The island was occupied for thousands of years by cultures of indigenous peoples, who had migrated from present-day Central and South America. In the 16th century, Spanish explorers in the Caribbean began to colonize Hispaniola. They adopted the native Taíno name Guárico for the area that is today known as "Cap‑Haïtien".[11] Due to the introduction of new infectious diseases, as well as poor treatment, the indigenous peoples population rapidly declined.

On the nearby coast Columbus founded his first community in the New World, the short-lived La Navidad. In 1975, researchers found near Cap‑Haïtien another of the first Spanish towns of Hispaniola: Puerto Real was founded in 1503. It was abandoned in 1578, and its ruins were not discovered until late in the twentieth century.[12]

The French occupied roughly a third of the island of Hispaniola from the Spanish in the early eighteenth century. They established large sugar cane plantations on the northern plains and imported tens of thousands of African slaves to work them. Cap‑Français became an important port city of the French colonial period and the colony's main commercial centre.[5] It served as the capital of the French colony of Saint-Domingue from the city's formal founding in 1711 until 1770, when the capital was moved to Port-au-Prince on the west coast of the island. After the slave revolution, this was the first capital of the Kingdom of Haiti under King Henri I, when the nation was split apart.

The central area of the city is between the Bay of Cap‑Haïtien to the east and nearby mountainsides, as well as the Acul Bay, to the west; these are increasingly dominated by flimsy urban slums. The streets are generally narrow and arranged in grids. As a legacy of the United States' occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934, Cap‑Haïtien's north–south streets were renamed as single letters (beginning with Rue A, a major avenue) and going to "Q", and its east–west streets with numbers from 1 to 26; the system is not followed outside the central city, where French names predominate. The historic city has numerous markets, churches, and low-rise apartment buildings (of three–four storeys), constructed primarily before and during the U.S. occupation. Much of the infrastructure is in need of repair. Many such buildings have balconies on the upper floors, which overlook the narrow streets below. With people eating outside on the balconies, there is an intimate communal atmosphere during dinner hours.

-

Engraving of Cap-Français in 1728

-

Fire of Cap Français, 21 June 1793

-

The French army led by Le Clerc lands in Cap Français (1802)

-

American Marines in 1915 defending the entrance gate in Cap-Haïten

-

Marine's base at Cap-Haïtien

Economy

[edit]

Cap-Haïtien is known as the nation's largest center of historic monuments and as such, it is a tourist destination. The bay, beaches and monuments have made it a resort and vacation destination for Haiti's upper classes, comparable to Pétion-Ville. Cap‑Haïtien has also attracted more international tourists at times, as it has been isolated from the political instability in the south of the island.

It has a wealth of French colonial architecture, which has been well preserved. During and after the Haitian Revolution, many craftsmen from Cap‑Haïtien, who were free people of color, fled to French-controlled New Orleans as they were under attack by the mostly African slaves. As a result, the two cities share many similarities in styles of architecture. Especially notable are the gingerbread houses lining the city's older streets.[citation needed]

Since 2021, there have been significant electrical outages in Cap Haïtien, due in large part to a lack of fuel. Those who can afford it have invested in solar energy.[13][14] A power plant built in Caracol to provide electricity to the Industrial Park reaches as far as Limonade 30 minutes from downtown Cap Haïtien.[14]

Tourism

[edit]Labadie and other beaches

[edit]

The walled Labadie (or Labadee) beach resort compound is located ten kilometres (6 mi) to the city's northwest. It serves as a brief stopover for Royal Caribbean International (RCI) cruise ships. Major RCI cruise ships dock weekly at Labadie. It is a private resort leased by RCI, which has generated the largest proportion of tourist revenue to Haiti since 1986. It employs 300 locals, allows another 200 to sell their wares on the premises, and pays the Haitian government US$6 per tourist.

The resort is connected to Cap‑Haïtien by a mountainous, recently paved road. RCI has built a pier at Labadie, completed in late 2009, capable of servicing the luxury-class large ships.[15]

Attractions include a Haitian market, numerous beaches, watersports, a water-oriented playground, and a zip-line.[16]

Cormier Plage is another beach on the way to Labadie, and there are also water taxis from Labadie to other beaches, like Paradis beach. In addition, Belli Beach is a small sandy cove with boats and hotels. Labadie village can be visited from here.[17]

Vertières

[edit]Vertières is the site of the Battle of Vertières, the last and defining battle of the Haitian Revolution. On November 18, 1803, the Haitian army led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines defeated a French colonial army led by the Comte de Rochambeau. The French withdrew their remaining 7,000 troops (many had died from yellow fever and other diseases), and in 1804, Dessalines' revolutionary government declared the independence of Haiti. The revolution had been underway, with some pauses, since the 1790s. In this last battle for independence, rebel leader Capois La Mort survived all the French bullets that nearly killed him. His horse was killed under him, and his hat fell off, but he kept advancing on the French, yelling, "En avant!" (Go forward!) to his men. He has become renowned as a hero of the revolution. The 18 of November has been widely celebrated since then as a Day of Army and Victory in Haiti.

Citadelle Henry and Sans-Souci Palace

[edit]The Citadelle Laferrière, also known as Citadelle Henry, or the Citadelle, is a large mountaintop fortress located approximately 27 kilometres (17 mi) south of the city of Cap‑Haïtien and eight kilometres (5 mi) beyond the town of Milot. It is the largest fortress in the Americas, and was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1982 along with the nearby Sans-Souci Palace. The Citadel was built by Henry Christophe, a leader during the Haitian slave rebellion and self-declared King of Northern Haiti, after the country gained its independence from France in 1804. Together with the remains of his Sans-Souci Palace, damaged in the 1842 earthquake, Citadelle Henry has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[18]

Bois Caïman

[edit]Bois Caïman (Haitian Creole: Bwa Kayiman), three kilometres (2 mi) south of road RN 1, is the place where Vodou rites were performed under a tree at the beginning of the slave revolution. For decades, maroons had been terrorizing slaveholders on the northern plains by poisoning their food and water. Makandal is the legendary (and perhaps historical) figure associated with the growing resistance movement. By the 1750s, he had organized the maroons, as well as many people enslaved on plantations, into a secret army. Makandal was murdered (or disappeared) in 1758, but the resistance movement grew.

At Bois Caïman, a maroon leader named Dutty Boukman held the first mass antislavery meeting secretly on August 14, 1791. At this meeting, a Vodou ceremony was performed, and all those present swore to die rather than to endure the continuation of slavery on the island. Following the ritual led by Boukman and a mambo named Cécile Fatiman, the insurrection started on the night of August 22–23, 1791. Boukman was killed in an ambush soon after the revolution began. Jean-François was the next leader to follow Dutty Boukman in the uprising of the slaves, the Haitian equivalent of the storming of the Bastille in the French Revolution. Slaves burned the plantations and cane fields, and massacred French colonists across the northern plains. They also attacked Cap-Français and some of the free people of color. Eventually the revolution gained the independence of Haiti from France and freedom for the slaves. The site of Dutty Boukman's ceremony is marked by a ficus tree. Adjoining it is a colonial well, which is credited with mystic powers.

Morne Rouge

[edit]Morne Rouge is eight kilometres (5 mi) to the south of Cap. It is the site of the sugar plantation known as "Habitation Le Normand de Mezy", known for several slaves who led the rebellion against the French.[19]

Disasters

[edit]1842 Cap-Haïtien earthquake

[edit]On 7 May 1842, an earthquake destroyed most of the city and other towns in the north of Haiti and the neighboring Dominican Republic. Among the buildings destroyed or significantly damaged was the Sans-Souci Palace. Ten thousand people were killed in the earthquake.[20] Its magnitude is estimated as 8.1 on the Richter scale.

2010 Haiti earthquake

[edit]In the wake of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which destroyed port facilities in Port-au-Prince, the Port international du Cap-Haïtien was used to deliver relief supplies by ship.[21]

As the city's infrastructure suffered little damage, numerous businessmen and many residents have moved here from Port-au-Prince. The airport is patrolled by Chilean UN troops since the 2010 earthquake, and several hundred UN personnel have been assigned to the city as part of the ongoing United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). They are working on recovery throughout the island.

After the earthquake, the port of Labadee was demolished and the pier enlarged and completely re-paved with concrete, which now allows larger cruise ships to dock, rather than tendering passengers to shore.

Cap-Haïtien fuel tanker explosion

[edit]On 14 December 2021, over 75 people were killed when a fuel tank truck overturned and later exploded in the Samari neighborhood of Cap-Haïtien.

Transport

[edit]Airports

[edit]Cap-Haïtien is served by the Cap-Haïtien International Airport (CAP), Haiti's second busiest airport.[22] It was a hub for Salsa d'Haiti prior to its cessation in 2013. American Airlines operated international flights to CAP for a number of years, but canceled their last connection in July, 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced passenger demand. American Airlines was the last major US flight operator to provide service to CAP and thereby Northern Haiti—in July, 2020, Cap-Haïtien became only accessible by air travel through limited flights from Port-au-Prince's Toussaint Louverture International Airport.[23] Spirit Airlines, which had previously canceled their service due to political unrest and low demand in 2019, announced in October, 2020 that they would resume limited service to CAP in December of the same year.[24]

Seaport

[edit]The Port international du Cap-Haïtien is Cap-Haïtien's main seaport. USAID financed $24 million of works to renovate the port beginning in May 2024.[25]

Roads

[edit]The Route Nationale#1 connects Cap-Haïtien with the Haitian capital city Port-au-Prince via the cities of Saint-Marc and Gonaïves.

The Route Nationale#3 also connects Cap-Haïtien with Port-au-Prince via the Central Plateau and the cities of Mirebalais and Hinche. Cap-Haïtien has one of the best grid systems in Haiti with its north–south streets were renamed as single letters (beginning with Rue A, a major avenue), and its east–west streets with numbers. The Boulevard du Cap-Haitian (also called the Boulevard Carenage) is Cap‑Haïtien's main boulevard that runs along the Atlantic Ocean in the northern part of the city.

Public transportation

[edit]Cap-Haïtien is served by tap tap and local taxis or motorcycles.

Health

[edit]Cap Haitien is served by the teaching hospital: Hôpital Universitaire Justinien.

Bildung

[edit]A union of four Catholic Church private schools have been present for two decades in Cap‑Haïtien. They have higher-level grades, equivalent to the lycées that feed the Écoles Normale Supérieure in France. They have high standards of academic excellence, selectivity in admissions, and generally their students come from the social and economic elite. Also, the lyceé Philippe Guerrier that was built in 1844 by the Haitian President, Philippe Guerrier, has been a fountain of knowledge for more than a century.

- Collège Notre-Dame du Perpetuel Secours des Pères de Sainte-Croix

- Collège Regina Assumpta des Sœurs de Sainte-Croix

- École des Frères de l'instruction Chrétienne

- École Saint Joseph de Cluny des Sœurs Anne-Marie Javoue

- Lyceé Philippe Guerrier built by the Haitian President, Philippe Guerrier in 1844.

Universitäten

[edit]Cap Haitien is home to the Cap-Haitien Faculty of Law, Economics and, Management; the Public University of the North in Cap Haitien (UPNCH). The new Université Roi Henry Christophe is nearby in Limonade.

Sport

[edit]Cap Haitien has the Parc Saint-Victor home of three major league teams: Football Inter Club Association, AS Capoise, and Real du Cap.

Communal sections

[edit]The commune consists of three communal sections, namely:

- Bande du Nord, urban (part of the commune of Cap-Haïtien) and rural

- Haut du Cap, urban (part of the commune of Cap-Haïtien) and rural

- Petit Anse, urban (commune of Petit Anse) and rural

Notable natives

[edit]- Pierre Nord Alexis (1820 – 1910), President of Haiti, 1902–1908.

- Tancrède Auguste (1856 – 1913), the 20th President of Haiti, 1912–1913.

- Étienne Chavannes (born 1939), a Haitian painter of crowd scenes

- Tyrone Edmond, Haitian-born model.

- Arly Larivière, Haitian Kompa musician and composer

- Yolette Lévy (1938–2018), Haitian-born Canadian politician and activist

- Lewis Page Mercier (1820–1875), Haitian educator and educator

- Alfred Auguste Nemours (1883–1955), military historian and diplomat

- Philomé Obin (1892–1986), artist and painter

- Leonel Saint-Preux (born 1985), footballer, played 41 games for Haiti

- Bruny Surin (born 1967), track and field runner, Olympic medalist, lives in Canada

Gallery

[edit]-

Front view of Sans-Souci Palace

-

Hotel de Ville (City Hall), site of the City Council, Cap-Haïtien.

-

A cruise ship at Labadie.

Television

[edit]Radio stations

[edit]- Bon Déjeuner! Radio, an internet radio station in Haiti, broadcasting from Cap-Haitien.

- Radyo Atlantik, 92.5 FM [29]

- Radio 4VEH (4VEF), 840 AM [30]

- Radio 4VEH, 94.7 FM [30]

- Radio 7 FM, 92.7 FM [31]

- Radio Cap-Haïtien

- Radio Citadelle, 91.1 FM

- Radio Étincelle

- Radio Gamma, 99.7 (based in Fort-Liberté) [32]

- Radio Lumière, 98.1 FM [33]

- Radio Méga, 103.7 FM

- Radio Sans-Souci FM, 106.9 FM

- Radio VASCO, 93.7 FM [34]

- Radio Vénus FM, 104.3 FM

- Sans Souci FM, 106.9 [35]

- Voix de l'Ave Maria, 98.5 FM

- Voix du Nord, 90.3 FM

- Radio Intermix, 93.1 FM: La Reference Radio en Haïti # 1

- Radio Paradis [36]

- Radio Nirvana, 97.3 FM [37]

- Radio Hispaniola

- Radio Maxima, 98.1.FM [38]

- Radio Voix de l'ile, 94.5 FM [39]

- Radio Digital, 101.3 FM [40]

- Radio Oxygene, 103.3 FM [41]

- Radio Passion, 101.7 FM Haïti [42]

- Radio City Inter Haïti

- La Radio de l'éducation

- Radio Multivers FM Cap haitien

- Toujours plus hauts

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Institut Haïtien de Statistique et d'Informatique (IHSI)

- ^ Sister Cities International Archived September 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Portland's Sister Cities - Portland, ME". portlandmaine.gov.

- ^ Clammer, Paul, ed. (2012). Haiti. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-84162-415-0.

- ^ a b Knight, Franklin W.; Liss, Peggy K. (1991). Atlantic Port Cities: Economy, Culture, and Society in the Atlantic World, 1650–1850. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780870496578.

- ^ King, Stewart R. (2001). Blue Coat or Powdered Wig: Free People of Color in Pre‑revolutionary Saint Domingue. University of Georgia Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780820342351.

- ^ Kuss, Malena (2007). Music in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Encyclopedic History. University of Texas Press. p. 254. ISBN 9780292784987.

- ^ Clammer, Paul; Grosberg, Michael; Porup, Jens (2008). Dominican Republic & Haiti. Country Guide Series. Lonely Planet. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-74104-292-4.

- ^ a b Coto, Dnica (2024-04-20). "Haiti's former capital seeks to revive its hey-day as gang violence consumes Port-au-Prince". Independent.

- ^ Maxineau, Gérard (2020-06-17). "Démolition de Shada 2 au Cap-Haïtien, bastion du gang « Ajivit »". Le Nouvelliste.

- ^ Mackenzie, Charles (1830). Notes on Haiti: Made During a Residence in that Republic. Vol. 1. p. 152.

- ^ Florida Museum of Natural History, Puerto Real.

- ^ peralta, Eyder (2024-04-18). "A portrait of Haitians trying to survive without a government". NPR.

- ^ a b Jameson Francisque (2022-06-09). "La ville du Cap-Haitien plongée dans le noir depuis six mois". Ayibo Post.

- ^ "Labadie". Expedia.com. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Labadie". The Washington Post. 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ Cameron, p. 406

- ^ "Citadelle Henry", UNESCO World Heritage Sites

- ^ Cameron, p. 409

- ^ Prepetit, Claude (9 October 2008), "Tremblements de terre en Haïti, mythe ou réalité ?" (PDF), Le Matin, vol. 33082[permanent dead link], quoting Moreau de Saint-Méry, Médéric Louis Élie, Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'Ile Saint Domingue and J. M. Jan, bishop of Cap-Haïtien (1972), Documentation religieuse, Éditions Henri Deschamps. "Cap-Haitian Earthquake of May 7, 1842". Archived from the original on 2011-12-21. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Thompson, Ginger; Cave, Damien (16 January 2010). "Officials Strain to Distribute Aid to Haiti as Violence Rises - NYTimes.com". The New York Times.

- ^ "Haiti renames airport for Hugo Chavez". The Big Story. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Charles, Jacqueline (July 1, 2020). "American Airlines reduces service to Haiti, cancels Miami-Cap-Haïtien route". Miami Herald.

- ^ Inc, Spirit Airlines (2020-10-01). "Spirit Airlines to Restore Flights to Cap-Haitien, Re-Activate Region's Only Nonstop Service to U.S." GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved 2020-11-19.

{{cite press release}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Sénat, Jean Daniel (2024-04-12). "Vers la réhabilitation du port international du Cap-Haïtien". Le Nouvelliste (in French).

- ^ "Radio Tele Pardadis". www.radioteleparadis.com.

- ^ "Home". radioteleafrica.com.

- ^ Index of / Archived February 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "AtLanTikHaiti.com". www.atlantikhaiti.com.

- ^ a b "Radio 4VEH - La Voix Évangélique d'Haïti". www.radio4veh.org. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ "Tele7 - Portada". www.tele7.com.

- ^ Radio Gamma fm, 99.7 MHz - Bienvenue Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Radio Lumiere - Home". www.radiolumiere.org.

- ^ "Radio Vasco". Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ Sans Souci FM Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Radio Tele Pardadis". www.radioteleparadis.com.

- ^ "Welcome radionirvanafm.com - BlueHost.com". www.radionirvanafm.com.

- ^ [1] "Radio Maxima 98.1 Fm". Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ [2] "Lavpoix de l'ile". Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Noel, Jackendy R. "Radio Tele Digital 101.3 FM Haiti, Musique, Actualites, Interview, Infos, Foot-ball, Education, Culture". radioteledigital.fr.ht.

- ^ [3] "Radio Oxygene Cap-Haitien - ACCEUIL". Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Radio Passion Haiti :: Sport Haiti, Actualités Haiti, Économie Haiti, Santé Haiti, Météo Haiti, Politique Haiti, Culture Haiti".

References

[edit]- Dubois, Laurent Haiti : the aftershocks of history. New York : Metropolitan Books, 2012.

- Popkin, Jeremy D. Facing racial revolution : eyewitness accounts of the Haitian Insurrection Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall. Haitian history : new perspectives. New York : Routledge, 2012.

External links

[edit] Cap-Haïtien travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cap-Haïtien travel guide from Wikivoyage- short article - Columbia encyclopedia

- The Louverture Project: Cap Haïtien - Article from Haitian history wiki.

- Konbit Sante's page on Cap-Haitien. Konbit Sante is a non-denominational mixed NGO.