Kyrgyz in China: Difference between revisions

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

At the end of the 3rd century BC, the Xiongnu conquered the ancestors of the Kyrgyz people who lived around the Kyrgyz Lake to the north of the Xiongnu. |

At the end of the 3rd century BC, the Xiongnu conquered the ancestors of the Kyrgyz people who lived around the Kyrgyz Lake to the north of the Xiongnu. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the Kyrgyz people were ruled by the Turks, and after the Tang Empire defeated the Turks, they belonged to the Protectorate of Yanran. Later, it was conquered by the Huihe Khanate, and it was called Xigas. In the 9th century, Xigas gradually became stronger. In 840 AD, it defeated the Uyghur Khanate, killed the khans and executed Khorabh, and established the Migas Khanate in the Tuva area. In the 10th century, with the rise of Khitan, Xigas became its vassal state. In the Yuan Dynasty, the Kyrgyz people were called Qierjisi or Jilijisi. At the end of the 16th century, the Junggar tribe in Mongolia gradually became stronger, and at the beginning of the 17th century, most of the Kyrgyz people became the tribes and territories of the Junggar.<ref name=1we3/><ref name=":0" /> |

||

The Kyrgyz traditional domain between the expanding Russia and the Qing Empire was gradually attacked by foreign forces, and shrank with the annexation of Russia and the Qing Dynasty.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zUIkDwAAQBAJ&q=qing+china+kyrgyz&pg=PT72|title=China's Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia|last=Parham|first=Steven|date=2017-02-14|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=9781786721259|language=en}}</ref> In the autumn of 1703, most of the four Kyrgyz tribes of Tuva, Yezer, Aletir and Aletisar in the Yenisei River in Siberia moved to the Issyk-Kul region and the Fergana Basin on the edge of the Qing Empire. and the nearby mountainous areas,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat5/4sub6/entry-4342.html#chapter-3|title=KYRGYZ IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE {{!}} Facts and Details|last=Hays|first=Jeffrey|website=factsanddetails.com|language=en|access-date=2018-02-28}}</ref> the Qing Dynasty documents called the Kyrgyz as Brut, and recorded the Kyrgyz tribes as Sayak, Sarbagash, Buku, Hosuochu, Qitai, Salou, Edegna , Monkordoer, Qilik, Baszi, Chongba Gash, Hushqi, Yuevash, Tiyit, Naiman, Shibchak, Neugut, Suletu, etc., The chiefs of the Kirgiz tribes who belonged to the Qing Dynasty were given the tops of the second to seventh grades, which were under the exclusive control of the counselor and minister of Kashgar, and the general Yili sent the leading ministers to inspect once every two years in the area close to Ili.<ref name=1we3/><ref name="CosmoCosmo2005">{{cite book|author1=Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo|author2=Nicola Di Cosmo|author3=Don J Wyatt|title=Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y1mQAgAAQBAJ&q=turki+merchants+gifts&pg=PA362|date=16 August 2005|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-79095-0|pages=362–}}</ref> |

The Kyrgyz traditional domain between the expanding Russia and the Qing Empire was gradually attacked by foreign forces, and shrank with the annexation of Russia and the Qing Dynasty.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zUIkDwAAQBAJ&q=qing+china+kyrgyz&pg=PT72|title=China's Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia|last=Parham|first=Steven|date=2017-02-14|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=9781786721259|language=en}}</ref> In the autumn of 1703, most of the four Kyrgyz tribes of Tuva, Yezer, Aletir and Aletisar in the Yenisei River in Siberia moved to the Issyk-Kul region and the Fergana Basin on the edge of the Qing Empire. and the nearby mountainous areas,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat5/4sub6/entry-4342.html#chapter-3|title=KYRGYZ IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE {{!}} Facts and Details|last=Hays|first=Jeffrey|website=factsanddetails.com|language=en|access-date=2018-02-28}}</ref> the Qing Dynasty documents called the Kyrgyz as Brut, and recorded the Kyrgyz tribes as Sayak, Sarbagash, Buku, Hosuochu, Qitai, Salou, Edegna , Monkordoer, Qilik, Baszi, Chongba Gash, Hushqi, Yuevash, Tiyit, Naiman, Shibchak, Neugut, Suletu, etc., The chiefs of the Kirgiz tribes who belonged to the Qing Dynasty were given the tops of the second to seventh grades, which were under the exclusive control of the counselor and minister of Kashgar, and the general Yili sent the leading ministers to inspect once every two years in the area close to Ili.<ref name=1we3/><ref name="CosmoCosmo2005">{{cite book|author1=Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo|author2=Nicola Di Cosmo|author3=Don J Wyatt|title=Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y1mQAgAAQBAJ&q=turki+merchants+gifts&pg=PA362|date=16 August 2005|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-79095-0|pages=362–}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 24 March 2022

The Kyrgyz (simplified Chinese: 柯尔克孜族; traditional Chinese: 柯爾克孜族; pinyin: Kē'ěrkèzīzú) are a Turkic ethnic group and form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. Mainly distributed in Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture in the southwest of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, a few are distributed in neighboring Wushi, Aksu City, Shache, Yingjisha, Tashkorgan and Pishan, as well as Turks, Zhaosu, Emin in northern Xinjiang , Bole, Jinghe and Gongliu. According to the fifth national census of the People's Republic of China, there are 160,875 Kyrgyz people in China.[1][2][3]

History

At the end of the 3rd century BC, the Xiongnu conquered the ancestors of the Kyrgyz people who lived around the Kyrgyz Lake to the north of the Xiongnu. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the Kyrgyz people were ruled by the Turks, and after the Tang Empire defeated the Turks, they belonged to the Protectorate of Yanran. Later, it was conquered by the Huihe Khanate, and it was called Xigas. In the 9th century, Xigas gradually became stronger. In 840 AD, it defeated the Uyghur Khanate, killed the khans and executed Khorabh, and established the Migas Khanate in the Tuva area. In the 10th century, with the rise of Khitan, Xigas became its vassal state. In the Yuan Dynasty, the Kyrgyz people were called Qierjisi or Jilijisi. At the end of the 16th century, the Junggar tribe in Mongolia gradually became stronger, and at the beginning of the 17th century, most of the Kyrgyz people became the tribes and territories of the Junggar.[2][4]

The Kyrgyz traditional domain between the expanding Russia and the Qing Empire was gradually attacked by foreign forces, and shrank with the annexation of Russia and the Qing Dynasty.[4] In the autumn of 1703, most of the four Kyrgyz tribes of Tuva, Yezer, Aletir and Aletisar in the Yenisei River in Siberia moved to the Issyk-Kul region and the Fergana Basin on the edge of the Qing Empire. and the nearby mountainous areas,[5] the Qing Dynasty documents called the Kyrgyz as Brut, and recorded the Kyrgyz tribes as Sayak, Sarbagash, Buku, Hosuochu, Qitai, Salou, Edegna , Monkordoer, Qilik, Baszi, Chongba Gash, Hushqi, Yuevash, Tiyit, Naiman, Shibchak, Neugut, Suletu, etc., The chiefs of the Kirgiz tribes who belonged to the Qing Dynasty were given the tops of the second to seventh grades, which were under the exclusive control of the counselor and minister of Kashgar, and the general Yili sent the leading ministers to inspect once every two years in the area close to Ili.[2][6]

The attitude of the Kyrgyz towards Russia was initially neutral as their first interaction with the Russian Empire was in the context of the Russo-Kazakh war, before Russia expanded into traditional Kyrgyz territory, the Kazakhs had begun to settle the Kyrgyz A series of raids were carried out, so the Kyrgyz were happy to gain an ally militarily superior to the Kazakhs, especially the Russian raids in the 1850s on the Kokand Khanate, which was hostile to the Kyrgyz clans. But in 1860 Cossacks from the Russian Empire sacked the Kyrgyz city of Bishkek and annexed the area for the Russian Empire, and by 1865 Kyrgyzstan was completely subordinate to Russia.[7][8]

With the increasing conflict between Russian settlers who move into traditional Kyrgyz lands and nomadic Kyrgyz people, the Kyrgyz people are sure that China will defeat Russia in the coming war due to China's greater benefits to the Kyrgyz people compared to Russia, Many Kyrgyz people moved to China, and Russia also believed that the Kyrgyz people would be the cause of a potential conflict with China, and began to drive the Kyrgyz people to China, causing their population in China to continue to increase. In 1916, in order to avoid massacres by the Russians, about 150,000 Kyrgyz people fled to China on a large scale, moving to Yili in the north, Aksu, Ushi, Kashgar, and Jiashi in the south.[9][10][11]

As a tribal alliance composed of various tribal groups, each Kyrgyz tribal group has its own leader. After Xinjiang was established as a province in 1884 and the Kyrgyz area was completely incorporated into the administrative management system in the 1930s, the traditional Kyrgyz nationality The clan and tribal system began to disintegrate gradually, but the influence of tribal concepts and tribal leaders still existed, which was more obvious in pastoral areas. On July 14, 1954, the Kyzilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture was announced.[2][12]

Culture

The majority of the Kyrgyz in China are herders, mainly raising camels and sheep. Their language and culture is very similar to the Kazakhs in China.Kyrgyz language is the mother tongue of the Kyrgyz nationality. The Kyrgyz people living in Aktao and other counties and the Uyghur people commonly use Uyghur language or both. Most of the Kyrgyz people in Turks and Zhaosu also use Kazakh and Chinese. Most of the Kyrgyz people who live in Kazakh and Mongolian ethnic groups commonly use or combine Kazakh, Mongolian and Chinese.[13][2][14]

Common dress for Kyrgyz men includes black or blue sleeveless long gowns made out of camel hair, sheep skin, or cotton cloth (in the summer). This robe is usually worn over a white embroidered shirt and leather trousers. Both genders wear leather boots but women's boots are embroidered as well. Kyrgyz women commonly wear a wide collarless jacket and vest over a long dress. Clothing accessories include leather belts which nomadic Kyrgyz tend to hang a flint (to start a fire) or a small knife on. Women routinely wear silver chains in their hair. Both the men and women wear a small corduroy skullcap which is sometimes placed over a high-topped leather hat. Women occasionally wear a bright headscarf over their cap.[15]

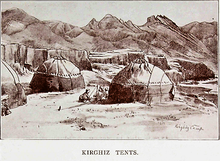

The Kyrgyz people first believed in shamanism. By the 18th century, most of the Kyrgyz people believed in Islam, and they combined many elements of shamanism and primitive beliefs. The Kut belief was the primitive religion of the Kyrgyz people. Most of the Kyrgyz people in Tacheng and Emin are influenced by the Mongolian people and believe in Tibetan Buddhism. The traditional handicraft industries of the Kyrgyz nationality include wood ware making, metal processing, textile embroidery, etc. They are famous for making felt products. There are many kinds of grass weaving, and most of them are made of Achnatherum splendens. The villages in the rural areas are mainly flat-roofed houses with brick and wood structures, and the pastoral areas use white felts to cover the yurts. The epic "Manas" occupies the primary place in Kyrgyz folk literature. The Kyrgyz people call the dance "Biyi", and the traditional musical instruments include Kumuzi, Ozkumuzi, Keyak, Qiuur, Doul, Bas, and Bandaru.[2][15]

References

- ^ "The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары". Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.173–191. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- ^ a b c d e f "柯尔克孜族". 中华人民共和国中央人民政府. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局:2000年第五次人口普查数据

- ^ a b Parham, Steven (2017-02-14). China's Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781786721259.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "KYRGYZ IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo; Don J Wyatt (16 August 2005). Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History. Routledge. pp. 362–. ISBN 978-1-135-79095-0.

- ^ Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 51. ISBN 9780313340130.

- ^ Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 9780313340130.

- ^ Alexander Douglas Mitchell Carruthers, Jack Humphrey Miller (1914). Unknown Mongolia: a record of travel and exploration in north-west Mongolia and Dzungaria, Volume 2. Lippincott. p. 345. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Alex Marshall (22 November 2006). The Russian General Staff and Asia, 1860-1917. Routledge. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-1-134-25379-1.

- ^ Sydykova, Zamira (20 January 2016). "Commemorating the 1916 Massacres in Kyrgyzstan? Russia Sees a Western Plot". The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst.

- ^ Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313340130.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (1996). China's Muslims. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. pp. 10. ISBN 0195875044.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (1996). China's Muslims. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. pp. 10. ISBN 0195875044.

- ^ a b Elliot, Sheila Hollihan (2006). Muslims in China. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. pp. 63-64. ISBN 1-59084-880-2.