Russian occupation of Crimea: Difference between revisions

m Bot: link syntax and minor changes |

Added a photo of the explosion of the Crimean Bridge. Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

On October 6, 2022, the administration of [[President of the United States]] [[Joe Biden]] assessed the likelihood of the liberation of Crimea by the Ukrainian military, noting that de-occupation for Ukraine is already quite possible. That is why such a scenario of events can no longer be discounted. The official emphasized that the [[2022 Ukrainian southern counteroffensive|pace of advancement of the Ukrainian military in the Kherson Oblast]] gives hope for the liberation of the peninsula temporarily occupied by Russia.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Oliphant |first=Roland |last2=Coughlin |first2=Con |last3=Bowman |first3=Verity |date=2022-10-05 |title=Ukraine could recapture Crimea as fleeing Russians continue to flounder |language=en-GB |work=The Telegraph |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/10/05/ukraine-could-recapture-crimea-fleeing-russians-continue-flounder/ |access-date=2022-10-07 |issn=0307-1235}}</ref> |

On October 6, 2022, the administration of [[President of the United States]] [[Joe Biden]] assessed the likelihood of the liberation of Crimea by the Ukrainian military, noting that de-occupation for Ukraine is already quite possible. That is why such a scenario of events can no longer be discounted. The official emphasized that the [[2022 Ukrainian southern counteroffensive|pace of advancement of the Ukrainian military in the Kherson Oblast]] gives hope for the liberation of the peninsula temporarily occupied by Russia.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Oliphant |first=Roland |last2=Coughlin |first2=Con |last3=Bowman |first3=Verity |date=2022-10-05 |title=Ukraine could recapture Crimea as fleeing Russians continue to flounder |language=en-GB |work=The Telegraph |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/10/05/ukraine-could-recapture-crimea-fleeing-russians-continue-flounder/ |access-date=2022-10-07 |issn=0307-1235}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Вибух-кримський-міст.png|thumb|[[2022 Crimean Bridge explosion|Crimean Bridge explosion]], October 2022]] |

|||

On October 8, a [[2022 Crimean Bridge explosion|fire broke out]] on the [[Crimean Bridge]] in [[Kerch]], the occupation authorities of the peninsula accused Ukraine of [[2022 Crimean Bridge explosion|undermining the crossing]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Crimean Bridge is on fire |url=https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2022/10/8/7370870/ |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=Ukrainska Pravda |language=en}}</ref> The [[Government of Ukraine|Ukrainian government's]] official [[Twitter]] account tweeted "sick burn" in response to the fire, while [[Mykhailo Podolyak|Mykhailo Podoliak]], a Ukrainian presidential advisor, called the damage a "beginning".<ref>{{Cite news |date=2022-10-08 |title=Crimean bridge: Explosion is 'the beginning', says Zelensky adviser |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63183404 |access-date=2022-10-08}}</ref> The [[Ministry of Defence (Ukraine)|Ministry of Defense of Ukraine]] compared the destruction of the Crimean Bridge to the [[Sinking of the Moskva|destruction of the cruiser ''Moskva'']]: "What's next, [[Russians|Russkies]]?".<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-10-08 |title=Key Bridge Linking Crimea to Russia Damaged as Truck Bomb Goes Off; Ukraine Says 'What's Next, Russkies?' |url=https://www.news18.com/news/world/soon-after-ukraine-explosion-fire-breaks-out-at-key-bridge-linking-mainland-russia-to-crimea-6123427.html |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=News18 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Міноборони про Кримський міст: «Що далі на черзі, росіяни?» |url=https://hromadske.radio/news/2022/10/08/minoborony-pro-kryms-kyy-mist-shcho-dali-na-cherzi-rosiiany |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=Громадське радіо |language=uk}}</ref> The Russian authorities in the Crimea accused the Ukrainian side of what happened.<ref name="после дня рождения">{{Cite web |title=Взрыв на Крымском мосту. Движение остановлено. Часть автомобильного моста обрушилась. Это произошло на следующий день после дня рождения Путина |url=https://meduza.io/feature/2022/10/08/vzryv-na-krymskom-mostu-dvizhenie-ostanovleno-chast-avtomobilnogo-mosta-obrushilas |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=[[Meduza]] |lang=ru}}</ref> |

On October 8, a [[2022 Crimean Bridge explosion|fire broke out]] on the [[Crimean Bridge]] in [[Kerch]], the occupation authorities of the peninsula accused Ukraine of [[2022 Crimean Bridge explosion|undermining the crossing]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Crimean Bridge is on fire |url=https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2022/10/8/7370870/ |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=Ukrainska Pravda |language=en}}</ref> The [[Government of Ukraine|Ukrainian government's]] official [[Twitter]] account tweeted "sick burn" in response to the fire, while [[Mykhailo Podolyak|Mykhailo Podoliak]], a Ukrainian presidential advisor, called the damage a "beginning".<ref>{{Cite news |date=2022-10-08 |title=Crimean bridge: Explosion is 'the beginning', says Zelensky adviser |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63183404 |access-date=2022-10-08}}</ref> The [[Ministry of Defence (Ukraine)|Ministry of Defense of Ukraine]] compared the destruction of the Crimean Bridge to the [[Sinking of the Moskva|destruction of the cruiser ''Moskva'']]: "What's next, [[Russians|Russkies]]?".<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-10-08 |title=Key Bridge Linking Crimea to Russia Damaged as Truck Bomb Goes Off; Ukraine Says 'What's Next, Russkies?' |url=https://www.news18.com/news/world/soon-after-ukraine-explosion-fire-breaks-out-at-key-bridge-linking-mainland-russia-to-crimea-6123427.html |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=News18 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Міноборони про Кримський міст: «Що далі на черзі, росіяни?» |url=https://hromadske.radio/news/2022/10/08/minoborony-pro-kryms-kyy-mist-shcho-dali-na-cherzi-rosiiany |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=Громадське радіо |language=uk}}</ref> The Russian authorities in the Crimea accused the Ukrainian side of what happened.<ref name="после дня рождения">{{Cite web |title=Взрыв на Крымском мосту. Движение остановлено. Часть автомобильного моста обрушилась. Это произошло на следующий день после дня рождения Путина |url=https://meduza.io/feature/2022/10/08/vzryv-na-krymskom-mostu-dvizhenie-ostanovleno-chast-avtomobilnogo-mosta-obrushilas |access-date=2022-10-08 |website=[[Meduza]] |lang=ru}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:09, 12 October 2022

A request that this article title be changed to Russian occupation of Crimea is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

| Part of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | |

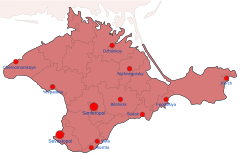

Territory in dark red has been controlled by the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol since 2014. | |

| Date | 20 February 2014[note 1] (10 years, 6 months, 2 weeks and 2 days) |

|---|---|

| Standort | Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol, Ukraine |

The Russian occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol is an ongoing military occupation within Ukraine by the Russian Federation, which began on 20 February 2014 when the military-political, administrative, economic and social order of Russia was spread to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea[8][9][10] and Sevastopol. The occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol was the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Currently, the recognition of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation is one of the fundamental conditions put forward by Russia to end the Russian invasion of Ukraine of 2022. In turn, Ukraine stated that it was ready to de-occupy Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol by military means.[11][12][13]

Occupation

On the night of February 26-27, Russian special forces seized and blocked the Supreme Soviet of Crimea and the Council of Ministers of Crimea. Representatives of the so-called Crimean militia, with the support of military personnel of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, seized other administrative buildings, airports in Simferopol and Sevastopol, communications facilities, the mass media, etc. autonomy of Crimea May 25, 2014 — on the day of the presidential elections in Ukraine. At the same time, the presence of a quorum is doubtful, since the media were not allowed to attend the meeting.[14] The Russian saboteur Igor Girkin, on the air of one of the Russian TV programs, admitted that the deputies of the Verkhovna Rada of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea to vote for the decision on the separation of Crimea from Ukraine were forcibly driven away by the so-called “militia”, and he personally was one of the commanders of this “militia”. Soon, the date of the referendum was changed twice: first moved to March 30, and then to March 16. The wording of the question was also changed - instead of expanding autonomy, it was about joining Russia. In fact, both "alternative" questions were formulated in such a way that they excluded Crimea's belonging to Ukraine.[15] At the same time, according to Ukrainian legislation, since Ukraine is a unitary state, the issue of separating the region can only be resolved at a national referendum. Given this, even before the referendum was held, the leaders of Australia, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, the United States and many others considered it illegal, and its results invalid.

On March 1, 2014, the Federation Council of the Russian Federation supported the appeal of President of Russia Vladimir Putin on permission to use the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation on the territory of Ukraine. The National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, in connection with the aggression from Russia, decided to put the Armed Forces of Ukraine on full alert and developed a "detailed plan of action in the event of direct war aggression from the Russian Federation."[16]

Annexation

On March 16, 2014, a “referendum on the status of Crimea” took place, where, according to official data, 96.77% of the inhabitants of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol voted for the reunification of the respective territories with the Russian Federation. On March 17, the Verkhovna Rada of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea proclaimed the independence of the Republic of Crimea, and on March 18, in the Georgievsky Hall of the Kremlin, President of Russia Vladimir Putin, together with the self-proclaimed Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov, the Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea Vladimir Konstantinov and the self-proclaimed life of Sevastopol Aleksei Chalyi, signed the Treaty on the Adoption of the Republic Crimea to Russia. On March 21, the Federation Council adopted a law on the ratification of the Treaty of March 18 and a law on the formation of new subjects of the federation — the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol, securing the annexation of these regions by Russia.

On March 27, 2014, the United Nations General Assembly supported the territorial integrity of Ukraine, recognizing Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol as its integral parts. 100 UN member states out of 194 voted for the relevant resolution. Only 11 countries voted against (Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela and Zimbabwe), 58 abstained.[17] The forced annexation of Crimea is not recognized by Ukraine,[18] is not recognized by the UN General Assembly, PACE,[19] OSCE PA, and also contradicts the decision of the Venice Commission, while the Russian authorities interpret it as “the return of Crimea to Russia.” According to the Law of Ukraine "On Ensuring the Rights and Freedoms of Citizens and the Legal Regime in the Temporarily Occupied Territory of Ukraine", the territory of the Crimean Peninsula is considered temporarily occupied territory as a result of Russian occupation.

Kerch Strait incident

On November 25, 2018, ships of the Ukrainian Navy, consisting of two small armored artillery boats "Berdyansk" and "Nikopol" and a raid tug "Yany Kapu" carried out a planned transition from the port of Odessa on the Black Sea to the port of Mariupol on the Sea of Azov. The Ukrainian side informed in advance about the route in accordance with international standards in order to ensure the safety of navigation. In the area of the Kerch Strait, they were stopped by a Russian tanker, which blocked the passage under the Crimean Bridge built by the occupying authorities. Contrary to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Treaty between Ukraine and the Russian Federation on Cooperation in the Use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait, the border ships of the Russian Federation (patrol border boats of the Sobol type, the Don PSKR, the Mongoose type boats, the Suzdalets MPK) committed aggressive actions against the ships of the Navy of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The border ship "Don" rammed a Ukrainian raid tug, as a result of which the ship's main engine, plating and railing were damaged, and a life raft was lost. Dispatching service of infidels refused to ensure the right of freedom of navigation, guaranteed by international agreements.[20] All three Ukrainian ships were captured by the Russians. 24 sailors were captured, 6 of whom were wounded. In Ukraine, on the same day, an urgent meeting of the National Security and Defense Council was convened to discuss the introduction of martial law. The next day, November 26, they approved the decision to introduce martial law for 30 days.[21]

Situation of ethnic Ukrainians under occupation

In the fall of 2014, the Russian authorities conducted a population census in the occupied Crimea, according to which there were 344.5 thousand Ukrainians on the peninsula (15.7%), and the native language was Ukrainian only 3.3% of the Crimean population is native. According to sociologist Iryna Bekeshkina, this reduction in the number of Ukrainians was due to the change in identification of part of the Ukrainian population from Ukrainians to Russians.[22] After the occupation, many ethnic Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars began to leave Crimea for mainland Ukraine.[13] As of August 15, 2019, 40,733 displaced people from the occupied peninsula were officially registered on the mainland of Ukraine.[23] In parallel with this, as the activists of the Crimean Tatar movement drew attention in 2018, several hundreds of thousands of Russians moved to Crimea with the assistance of the Russian authorities during the 4 years of occupation.[13][11] All this creates grounds for further fundamental changes in the ethnic structure of the peninsula.[13]

After the occupation of Crimea, Ukrainians became one of the ethnic communities of the peninsula most discriminated against by the occupying Russian authorities. The occupying power persecutes Ukrainian public figures, carries out anti-Ukrainian propaganda, makes xenophobic and chauvinist statements, persecutes Ukrainian religious communities, bans the activities of Ukrainian public and political organizations, restricts the use of the Ukrainian language and Ukrainian national symbols.[11][12] Thus, as early as the first half of 2014, Ukrainian-language signs were replaced with Russian ones,[12] in April 2014, the monument to Petro Sahaydachny and a commemorative sign in honor of the 10th anniversary of the Naval Forces of Ukraine were dismantled in Sevastopol,[24] in August 2014, it was announced that 250 Ukrainian language and literature teachers would be retrained in Russian,[25] in September 2014, the Faculty of Ukrainian Language was liquidated at the Tavri University (a department of Ukrainian philology was created instead),[26] in November 2014, the Crimean Academic Ukrainian Musical Theater was renamed the State Academic Musical Theater of the Republic of Crimea, and the only Ukrainian school-gymnasium in Simferopol was transferred to the Russian language of instruction and renamed to Simferopol Academic Gymnasium,[27] in December 2014, the Ukrainian children's theater studio "Svitanok" closed due to pressure,[28] in March 2016, the Lesia Ukrainka Museum in Yalta was closed for renovation,[29] in the same month, the Russian FSB searched the premises of the Ukrainian society "Prosvita" in Sevastopol, where they seized more than 250 "extremist materials".[30] The power structures of the occupation authorities detained a number of Ukrainian figures, in particular, Andriy Shchekun, Anatoliy Kovalskyi and others, some of the detainees were tortured.[25] The Russian military seized most of the churches of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine —as of October 2018, 38 out of 46 Ukrainian parishes in Crimea stopped working.[31] As of June 2019, only one OCU church remained in operation, but it was also looted by a court decision under the guise of repairs. According to Archbishop of Simferopol and Crimea Klyment, these hostile actions of the Russian occupying power towards the Ukrainian Church are aimed at the complete destruction of Ukrainian identity and Ukrainians as a separate nation in Crimea.[32]

In May 2015, the Ukrainian Cultural Center was established in Crimea, whose participants aimed to preserve Ukrainian culture and language on the peninsula.[33][34][35] Members of the center were repeatedly detained by Russian law enforcement agencies for conducting events to celebrate Ukrainian commemorative dates, some of the participants were searched at home, several were held administratively liable by a Russian court, and they were persecuted for their views at the everyday level.[33][34][36] In August 2017, the center started publishing the newspaper "Krymsky Teren" in Ukrainian and Russian.[36]

In 2015, after the persecution of members of the UCC, the organization "Ukrainian Community of Crimea" was created, headed by Oleg Usyk, a member of "United Russia", but it later ceased to exist. In 2018, a new legal public organization "Ukrainian Community of Crimea" was founded in Crimea, headed by Anastasia Hrydchyna, a member of the Young Guard of United Russia. This organization expresses support for the actions of the Russian authorities, denies the persecution of Ukrainians on the peninsula, participates in official events of the local occupation authorities, holds several congresses of the Ukrainian diaspora in Crimea, and created the Ukrainian-language website "Pereyaslavska rada 2.0". According to historian Andrii Ivanets and journalists of the Krim.Realii project, in fact this organization does not care about the problems of Ukrainians in Crimea and was created as a means of information warfare.[37]

According to the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea adopted in April 2014, Ukrainian became one of the official languages of this subject (along with Russian and Crimean Tatar).[38] Despite this, the sphere of use of the Ukrainian language is constantly shrinking. After the occupation of 2014, the study of the Ukrainian language on the peninsula was made optional, and its use in official records was stopped altogether.[39] The number of students with Ukrainian language of instruction continues to decrease. According to official Russian statistics, 12,892 students studied Ukrainian in the 2016/2017 academic year, and 6,400 students in the 2017/2018 academic year.[40] At the same time, according to Ukrainian and international observers, the real number of students with the Ukrainian language of instruction is much lower than officially declared. According to Crimean human rights group, during the occupation, the number of students studying Ukrainian decreased 31 times —from 13,589 students in 2013 to 371 students in 2016.[41] In April 2017, following Ukraine's appeal, the International Court of Justice UN in The Hague considered the case of Russia's violation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and adopted a decision according to which Russia should provide opportunities for teaching in the Ukrainian language on the peninsula.[42] According to the UN, in the 2017/2018 school year, there were 318 students in Crimea who studied in Ukrainian.[43] Before the occupation, there were 7 Ukrainian schools in Crimea, but by 2018 all of them were translated into Russian.[40] According to official data of the Russian Ministry of Education of the Crimea, in the 2018/2019 school year in the Crimea, out of 200,700 children, only 249 (0.2%) studied in the Ukrainian language, there was one Ukrainian-language school and 5 schools with 8 classes with the Ukrainian language of instruction. According to the report of the Crimean human rights group in 2019, not a single school remained in Crimea with the Ukrainian language of instruction, and there were even fewer Ukrainian-language classes than officially claimed.[44]

Some activists (in particular, the Crimean Tatars, who have a smaller but more organized community than Ukrainians) note that, despite the large statistical number, the majority of ethnic Ukrainians in Crimea rarely have pro-Ukrainian political views. At the same time, a number of Crimean Ukrainians do not agree with this opinion.[45]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

Shortly before the start of negotiations, Vladimir Putin's press secretary Dmitry Peskov, in an interview with Reuters, outlined the main requirements for Ukraine, one of which was the recognition of Crimea as Russian.[46] President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy said on the air of the ABC TV channel that he was ready to discuss the issues of Crimea and Donbas, but as part of Ukraine.[47]

On March 29, 2022, the head of the Ukrainian delegation, Mykhailo Podoliak, proposed to negotiate the status of Crimea and Sevastopol for 15 years.[48] At the same time, both Moscow and Kyiv should refrain from resolving this issue by military means throughout this period. Vladimir Medinsky, in turn, said that this does not correspond to the Russian position.[49] According to the statements of Mykhailo Podoliak and David Arakhamia after the negotiations, Ukraine proposed to freeze the issue of the status of Crimea for 15 years, proposed the conclusion of an international treaty on security guarantees, which would be signed and ratified by all countries acting as guarantors of Ukraine's security.[50][51] But the negotiation process was suspended in May 2022.[52]

On August 9, 2022, explosions occurred at the Saky military airfield in Crimea.[53] As a result of a fire and explosions at the airfield used as the main air force base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, from 7 to 11 Su-24 and Su-30SM aircraft were destroyed.[54][55][56][57][58] On September 7, 2022, the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Valerii Zaluzhnyi announced that it had launched a missile attack on the airfield.[59][60]

On August 23, 2022, due to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation, the second summit of the Crimea Platform was held online. The event was attended by more than 60 participants — leaders of countries and international organizations. They made statements in support of Ukraine.[61][62]

On August 29, 2022, President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky said that the Russian-Ukrainian war would end exactly where it began in 2014 - with the entry of Ukrainian troops to the state border in 1991, the liberation of the previously occupied territories of Ukraine, including Donbass and Crimea from the Russians.[63][64]

On September 28, 2022, the commander of the US Army in Europe, retired Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, is convinced that the Armed Forces of Ukraine will be able to push the Russian military back to their positions on February 23 by the end of this year, and by mid-2023 the Defense Forces can enter the temporarily occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea.[65] On September 30, 2022, the head of the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense, Kyrylo Budanov, stated that “Ukraine will return to the occupied Crimea - this will happen with weapons and pretty soon. The liberation of Crimea will not take place in the summer, but before the end of spring, perhaps a little earlier.”[66]

On October 6, 2022, the administration of President of the United States Joe Biden assessed the likelihood of the liberation of Crimea by the Ukrainian military, noting that de-occupation for Ukraine is already quite possible. That is why such a scenario of events can no longer be discounted. The official emphasized that the pace of advancement of the Ukrainian military in the Kherson Oblast gives hope for the liberation of the peninsula temporarily occupied by Russia.[67]

On October 8, a fire broke out on the Crimean Bridge in Kerch, the occupation authorities of the peninsula accused Ukraine of undermining the crossing.[68] The Ukrainian government's official Twitter account tweeted "sick burn" in response to the fire, while Mykhailo Podoliak, a Ukrainian presidential advisor, called the damage a "beginning".[69] The Ministry of Defense of Ukraine compared the destruction of the Crimean Bridge to the destruction of the cruiser Moskva: "What's next, Russkies?".[70][71] The Russian authorities in the Crimea accused the Ukrainian side of what happened.[72]

Analytics

Ukrainian historians and politicians assumed a similar development of events back in 2008 during the Russo-Georgian War. Experts pointed out that the Russian Federation only needed a pretext to start annexing the peninsula. The events at the Euromaidan and the Revolution of Dignity became such an occasion.[73]

On March 2, 2014, in an address to the UN Security Council, Ukrainian Ambassador Yuri Sergeyev called on the international community to "do everything possible" to stop the Russian act of aggression. He stressed that the number of Russian troops in Crimea is growing "by the hour." Russian Ambassador Vitaly Churkin said "colder heads must prevail" and the West must stop escalating the conflict by encouraging the protesters. US Ambassador Samantha Power told the session that Russia allowing the use of force is "dangerous and destabilizing."[74]

On March 2, 2014, The Wall Street Journal indicated that Putin's actions had brought the threat of war to the heart of Europe for the first time since the Cold War.

On April 15, 2014, British diplomat Charles Crawford wrote that he believed that Ukraine was Putin's testbed in his plans to revive the Russian Empire. The annexation of Crimea took place immediately, but the further conquest of Ukraine will be carried out by the method of a thousand cuts.

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Danylo Liubkivskyi:

In Crimea, Russia introduced censorship as a disease, intolerance of minorities, restriction freedom of Speech, unfair justice, administrative pressure and intimidation dissenters.

— Danylo Liubkivskyi, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, July 8, 2014

In November 2014, Andrey Illarionov, a former adviser to President of Russia Vladimir Putin, claimed that planning for a Russian invasion began long before Yanukovych's appeal.[75]

In January 2017, Ilya Ponomarev, a Russian politician and member of the State Duma of Russia (Fair Russia faction), claimed that the leadership of the annexation of Crimea was entrusted to Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Vladimir Putin's aide Vladislav Surkov.[76]

On December 17, 2019, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine recalled that Russia's actions in Crimea and Donbas fully fall under the definition of aggression in accordance with UN General Assembly Resolution 1976:[77]

Since 2014, Ukraine has been constantly qualifying the internationally illegal actions of the Russian Federation in Crimea and Donbas as an act of aggression. We clearly and consistently prove that such actions of the Russian Federation fully fall within the definition of aggression in accordance with paragraphs a), b), c), d), e) and g) of Article 3 of the Annex to UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (XXIX) “Definition aggression”, adopted 45 years ago.

— Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, December 17, 2019, statement

Control of settlements

See also

- Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine

- Russian occupation of Chernihiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Donetsk Oblast

- Russian occupation of Kharkiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Kherson Oblast

- Russian occupation of Kyiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Luhansk Oblast

- Russian occupation of Mykolaiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Sumy Oblast

- Russian occupation of Zaporizhzhia Oblast

- Russian occupation of Zhytomyr Oblast

- Snake Island during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Annexation of Southern and Eastern Ukraine

- Day of Resistance to Occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol

References

- ^ a b McDermott, Roger N. (2016). "Brothers Disunited: Russia's use of military power in Ukraine". In Black, J.; Johns, Michael (eds.). The Return of the Cold War: Ukraine, the West and Russia. London. pp. 99–129. doi:10.4324/9781315684567-5. ISBN 9781138924093. OCLC 909325250.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "7683rd meeting of the United Nations Security Council. Thursday, 28 April 2016, 3 p.m. New York".

Mr. Prystaiko (Ukraine): ... In that regard, I have to remind the Council that the official medal that was produced by the Russian Federation for the so-called return of Crimea has the dates on it, starting with 20 February, which is the day before that agreement was brought to the attention of the Security Council by the representative of the Russian Federation. Therefore, the Russian Federation started – not just planned, but started – the annexation of Crimea the day before we reached the first agreement and while President Yanukovych was still in power.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) "'Nasha' Poklonsky promises to the 'Berkut' fighters to punish the participants of the Maidan", Segodnya (20 March 2016)

- ^ "Putin describes secret operation to seize Crimea". Yahoo News. 8 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Putin reveals secrets of Russia's Crimea takeover plot". BBC News. 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin describes secret meeting when Russia decided to seize Crimea". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Russia's Orwellian 'diplomacy'". unian.info. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine clarified the date of the beginning of the Russian occupation of Crimea — February 20, 2014 // Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, September 15, 2015

- ^ "The President signed the Law, which defines February 20, 2014 as the date of the beginning of the temporary occupation of the territory of Ukraine". Archived from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Annexation, occupation, "accession" of Crimea or "establishment of Russian control" over Crimea - which term is correct? / Why are the phrases "annexed Crimea", "annexation of Crimea" not quite correct?". Crimea in the context of occupation: Q&A guide for the media (PDF). Kyiv: Human rights center ZMINA — Crimean human rights group — Presidential representative of Ukraine in Crimea. 2020. pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b c "Zelenskyi: War started in Donbas and Crimea, it will end there". Slovo i Dilo (in Ukrainian) (published 2022-08-30). 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06. Cite error: The named reference ":1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Oliphant, Roland (2022-10-05). "Ukraine could recapture Crimea as fleeing Russians continue to flounder". The Telegraph. 0307-1235. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) Cite error: The named reference ":2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d "Ukraine may enter occupied Crimea by late spring, says intelligence chief". Ukrainska Pravda (published 2022-09-30). 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Media: The Verkhovna Rada of the ARC cannot consider the issue of the all-Ukrainian referendum - the deputies do not have a quorum". www.unian.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "The issue of the Crimean referendum leaves no choice - only exit from Ukraine, the lawyer said". espreso.tv (in Ukrainian). March 6, 2014 [March 6, 2014]. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Turchynov instructed to bring the Armed Forces to full combat readiness". Українська правда (in Ukrainian). March 1, 2014. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "General Assembly resolution demands end to Russian offensive in Ukraine". UN News. 2022-03-02. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Ukraine never to recognize annexation Crimea by Russia – Yatseniuk". www.unian.info. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "PACE condemns illegal annexation of the Crimea". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ Pickrell, Ryan. "Shocking video shows the exact moment a suspected Russian ship rams a Ukrainian boat during a tense naval clash". Business Insider. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Ukraine Declares Martial Law Along Borders With Russia, Black Sea". VOA. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Перепис населення в Криму: чому росіян стало більше, а українців – менше" [Population census in Crimea: why there are more Russians and fewer Ukrainians]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "На материковій Україні на обліку перебуває 40 733 переселенця з Криму і Севастополя – міністерство" [40,733 migrants from Crimea and Sevastopol are registered in mainland Ukraine - the ministry]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "У Севастополі пам'ятники Сагайдачному і ВМС України замінять російським адміралом" [In Sevastopol, the monuments to Sahaidachny and the Navy of Ukraine will be replaced by a Russian admiral]. Українська правда (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b "В анексованому Криму вчителів української перекваліфікують на вчителів російської" [In the annexed Crimea, Ukrainian teachers are being retrained as Russian teachers]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "В Таврическом университете ликвидировали факультет украинской филологии" [The faculty of Ukrainian philology was liquidated at the Tavri University]. Центр журналістських розслідувань (in Ukrainian). 2014-09-13. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Українське в Криму? Знищити!" [Ukrainian in Crimea? Destroy!]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Придушити все українське? У Криму закрилася дитяча театральна студія" [Suppress everything Ukrainian? A children's theater studio was closed in Crimea]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Музей Лесі Українки у Ялті закрили. Назавжди?" [The museum of Lesya Ukrainka in Yalta was closed, the Russian authorities say - for repairs, writers - forever]. Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ Цензор.НЕТ. "ФСБ провела обшуки в українській "Просвіті" в окупованому Севастополі: вилучено 250 томів "екстремістської літератури". ВІДЕО". Цензор.НЕТ (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "В оккупированном Крыму 38 из 46 парафий УПЦ КП прекратили существование". www.ukrinform.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ a b "У Сімферополі запрацював Український культурний центр – DW – 29.05.2015". dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b "Долі кримських активістів - через два роки після анексії – DW – 16.03.2016". dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Український центр у Криму: "Ми втомилися боятись" – DW – 25.03.2016". dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b "У Криму обшукали активістку Українського культурного центру – DW – 29.08.2018". dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Чим займається російська «Українська громада Криму»". Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ Конституция Республики Крым от 11.04.2014

- ^ "«Щасливі українці» і українська мова в окупованому Криму". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b "У Криму не залишилось україномовних шкіл – DW – 28.08.2018" [There are no Ukrainian-language schools left in Crimea]. dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Кількість українських класів у Криму скоротилася у 31 раз за три роки – моніторинг" [The number of Ukrainian classes in Crimea decreased 31 times in three years - monitoring]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Київ частково виграв – гаазький експерт" [Kyiv partially won - the Hague expert]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "ООН: У Криму українською навчаються лише 318 дітей – DW – 13.09.2018" [UN: Only 318 children study Ukrainian in Crimea]. dw.com (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "У Криму не залишилося жодної школи з навчанням українською мовою – правозахисники" [There is not a single school left in Crimea with instruction in the Ukrainian language - human rights defenders]. Крым.Реалии (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Правда і неправда про кримських українців" [Truth and falsehood about Crimean Ukrainians]. tyzhden.ua. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Russia no longer requesting Ukraine be 'denazified' as part of ceasefire talks". Financial Times. 2022-03-28. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Video The Zelenskyy Interview: David Muir Reporting | ABC News Exclusive". ABC News. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Ukraine proposes talks on Crimea over the next 15 years". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ Reuters (2022-03-30). "Russia says Ukraine willing to meet core demands, but work continues". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Sukhov, Oleg (2022-03-29). "Ukraine seeks security guarantees 'stronger than NATO's,' outlines other terms for peace deal with Russia". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Украина предложила на 15 лет заморозить вопрос о статусе Крыма. Россия решила «кардинально сократить военную активность» на части фронта Главные итоги переговоров в Стамбуле". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Zelensky's office confirms Ukraine-Russia peace talks suspended". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ Hayda, Julian (2022-08-13). "Who was behind the explosions in Crimea? Ukraine and Russia aren't saying". NPR. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Russian warplanes destroyed in Crimea airbase attack, satellite images show". the Guardian. 2022-08-11. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Wesley Culp (2022-08-13). "Someone Is Lying: Ukraine and Russia Tell Different Tales About Crimean Airbase Blasts". 19FortyFive. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (2022-08-10). "Damage at Air Base in Crimea Worse Than Russia Claimed, Satellite Images Show". The New York Times. 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Jack Buckby (2022-08-12). "Putin Is Angry: Ukraine Special Forces Were Behind Crimea Attack". 19FortyFive. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ Gokul Pisharody (2022-08-12). "Britain says Crimea blasts degrade Russia's Black Sea aviation fleet". Reuters.

- ^ "Saky airfield: Ukraine claims Crimea blasts responsibility after denial". BBC News. 2022-09-07. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Ukraine's General Staff confirms that air bases in Crimea were hit with Ukrainian missiles". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Secretary General took part in Second Summit of Crimea Platform". www.coe.int. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ admin (2022-08-22). "The Second Crimean Platform Summit". GTInvest. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Zelenskyi: War started in Donbas and Crimea, it will end there". Slovo i Dilo (in Ukrainian) (published 2022-08-30). 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Ukraine war must end with liberation of Crimea – Zelensky". BBC News. 2022-08-10. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "JAV generolas: kitų metų viduryje Ukrainos kariuomenė bus Kryme". lrt.lt (in Lithuanian). 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Ukraine may enter occupied Crimea by late spring, says intelligence chief". Ukrainska Pravda (published 2022-09-30). 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland; Coughlin, Con; Bowman, Verity (2022-10-05). "Ukraine could recapture Crimea as fleeing Russians continue to flounder". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Crimean Bridge is on fire". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Crimean bridge: Explosion is 'the beginning', says Zelensky adviser". BBC News. 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Key Bridge Linking Crimea to Russia Damaged as Truck Bomb Goes Off; Ukraine Says 'What's Next, Russkies?'". News18. 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Міноборони про Кримський міст: «Що далі на черзі, росіяни?»". Громадське радіо (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Взрыв на Крымском мосту. Движение остановлено. Часть автомобильного моста обрушилась. Это произошло на следующий день после дня рождения Путина". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ "Крым, Донбасс, Порошенко: какие прогнозы оправдались после Евромайдана - BBC Ukrainian". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- ^ "Ukraine Tells Russia Invasion Means War // bloomberg.com (англ.)". Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Russian insider says Putin openly planned invasion of Ukraine since 2003 |Euromaidan Press |". web.archive.org. 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Ilya Ponomarev named two curators of the seizure of Crimea by Russia". web.archive.org. Khvylia. 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "МЗС: Дії РФ у Криму та на Донбасі підпадають під визначення агресії в резолюції ГА ООН". web.archive.org. 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ There remain "some contradictions and inherent problems" regarding date on which the annexation began.[1] Ukraine claims 20 February 2014 as the date of "the beginning of the temporary occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia", citing timeframe inscribed on the Russian medal "For the Return of Crimea",[2] and in 2015 the Ukrainian parliament officially designated the date as such.[3] In early March 2015, President Putin stated in a Russian film about annexation of Crimea that he ordered the operation to "restore" Crimea to Russia following an all-night emergency meeting of 22–23 February 2014,[1][4][5][6] and in 2018 Russian Foreign Minister claimed that earlier "start date" on the medal was due to "technical misunderstanding".[7]