Crop factor: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m wording clarification |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

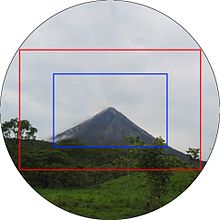

[[Image:Crop Factor.JPG|thumb|The outer, red box displays what a 24×36 mm sensor would see, the inner, blue box displays what a 15×23 mm sensor would see. The actual image circle of most lenses designed for 35 mm SLR format |

[[Image:Crop Factor.JPG|thumb|The outer, red box displays what a 24×36 mm sensor would see, the inner, blue box displays what a 15×23 mm sensor would see. (The actual image circle of most lenses designed for 35 mm SLR format would actually extend further beyond the red box than shown in the above image.)]] |

||

In [[digital photography]], a '''crop factor''' is related to the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format (actually it is the square root of this ratio of areas, since it is defined as the ratio of the diagonals instead of the ratio of the areas, see just below); most often, this term is applied to [[digital camera]]s, relative to [[135 film|35 mm film format]] as a standard. In the case of digital cameras, the imaging device would be a [[digital sensor]]. The most commonly used definition of crop factor is the ratio of a 35 mm frame's diagonal (43.3 mm) to the diagonal of the [[image sensor]] in question; that is, CF=diag<sub>35mm</sub> / diag<sub>sensor</sub>. Given the same 3:2 aspect ratio as 35mm's 36mm x 24mm area, this is equivalent to the ratio of heights or ratio of widths; the ratio of sensor areas is the ''square'' of the crop factor. |

In [[digital photography]], a '''crop factor''' is related to the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format (actually it is the square root of this ratio of areas, since it is defined as the ratio of the diagonals instead of the ratio of the areas, see just below); most often, this term is applied to [[digital camera]]s, relative to [[135 film|35 mm film format]] as a standard. In the case of digital cameras, the imaging device would be a [[digital sensor]]. The most commonly used definition of crop factor is the ratio of a 35 mm frame's diagonal (43.3 mm) to the diagonal of the [[image sensor]] in question; that is, CF=diag<sub>35mm</sub> / diag<sub>sensor</sub>. Given the same 3:2 aspect ratio as 35mm's 36mm x 24mm area, this is equivalent to the ratio of heights or ratio of widths; the ratio of sensor areas is the ''square'' of the crop factor. |

||

Revision as of 21:25, 11 May 2009

In digital photography, a crop factor is related to the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format (actually it is the square root of this ratio of areas, since it is defined as the ratio of the diagonals instead of the ratio of the areas, see just below); most often, this term is applied to digital cameras, relative to 35 mm film format as a standard. In the case of digital cameras, the imaging device would be a digital sensor. The most commonly used definition of crop factor is the ratio of a 35 mm frame's diagonal (43.3 mm) to the diagonal of the image sensor in question; that is, CF=diag35mm / diagsensor. Given the same 3:2 aspect ratio as 35mm's 36mm x 24mm area, this is equivalent to the ratio of heights or ratio of widths; the ratio of sensor areas is the square of the crop factor.

This ratio is also commonly referred as a focal length multiplier ("FLM") since multiplying a lens focal length by the crop factor or FLM gives the focal length of a lens that would yield the same field of view if used on the reference format.

The term format factor is sometimes also used, and is a more neutral term that corresponds to the German word for this concept, Formatfaktor.

Einführung

The terms crop factor and focal length multiplier were coined in recent years in an attempt to help 35 mm film format SLR photographers understand how their existing ranges of lenses would perform on newly introduced DSLR cameras which had sensors smaller than the 35 mm film format, but often utilized existing 35 mm film format SLR lens mounts. Using an FLM of 1.5, for example, a photographer might say that a 50 mm lens on his DSLR "acts like" its focal length has been multiplied by 1.5, by which he means that it has the same field of view as a 75 mm lens on the film camera that he is more familiar with. Of course, the actual focal length of a photographic lens is fixed by its optical construction, and does not change with the format of the sensor that is put behind it.

Most DSLRs on the market have nominally APS-C-sized image sensors, smaller than the standard 24×36 mm (35 mm) film frame. For example, many Canon DSLRs use a sensor that measures 22.5 mm × 15 mm. The result is that the image sensor captures image data from a smaller area than a 35 mm film SLR camera would, effectively cropping out the corners and sides that would be captured by the 36 mm × 24 mm 'full-size' film frame.

Because of this crop, the effective field of view (FOV) is reduced by a factor proportional to the ratio between the smaller sensor size and the 35 mm film format (reference) size.

For most DSLR cameras, this factor is 1.3–2.0×. For example, a 28 mm lens delivers a moderately wide-angle FOV on a 35 mm format full-frame camera, but on a camera with a 1.6 crop factor, an image made with the same lens will have the same field of view that a full-frame camera would make with a ~45 mm lens (28 × 1.6 = 44.8). This narrowing of the FOV is a disadvantage to photographers when a wide FOV is desired. Ultra-wide lens designs become merely wide; wide-angle lenses become 'normal'. However, the crop factor can be an advantage to photographers when a narrow FOV is desired. It allows photographers with long-focal-length lenses to fill the frame more easily when the subject is far away. A 300 mm lens on a camera with a 1.6 crop factor delivers images with the same FOV that a 35 mm film format camera would require a 480 mm lens to capture.

Digital lenses

Most SLR camera and lens manufacturers have addressed the concerns of wide-angle lens users by designing lenses with shorter focal lengths, optimized for the DSLR formats. In most cases, these lenses are designed to cast a smaller image circle that would not cover a 24×36 mm frame, but is large enough to cover the smaller 16×24 mm (or smaller) sensor in most DSLRs. Because they cast a smaller image circle, the lenses can be optimized to use less glass and are sometimes physically smaller and lighter than those designed for full-frame cameras.

Lenses designed for the smaller digital formats include Canon EF-S lenses, Nikon DX lenses, Olympus Four Thirds System lenses, Sigma DC lenses, Tamron Di-II lenses, Pentax DA lenses, and Sony Alpha (SAL) DT lenses. Such lenses usually project a smaller image circle than lenses that were designed for the full-frame 35 mm format. Nevertheless, the crop factor or FLM of a camera has the same effect on the relationship between field of view and focal length with these lenses as with any other lens, even though the projected image is not as severely "cropped". In this sense, the term crop factor sometimes has confusing implications; the alternative term "focal length multiplier" is sometimes used for this reason.

Crop factor of point-and-shoot cameras

Smaller, non-DSLR, consumer cameras, typically referred to as point-and-shoot cameras, can also be characterized as having a crop factor or FLM relative to 35 mm format, even though they do not use interchangeable lenses or lenses designed for a different format. For example, the so-called "1/1.8-inch" format with a 9 mm sensor diagonal has a crop factor of almost 5 relative to the 43.3 mm diagonal of 35 mm film. Therefore, these cameras are equipped with lenses that are about one-fifth of the focal lengths that would be typical on a 35 mm point-and-shoot film camera. In most cases, manufacturers label their cameras and lenses with their actual focal lengths, but in some cases they have chosen to instead multiply by the crop factor (focal length multiplier) and label the 35 mm equivalent focal length. Reviewers also sometimes use the 35 mm-equivalent focal length as a way to characterize the field of view of a range of cameras in common terms.

For example, the Canon Powershot SD600 lens is labeled with its actual focal length range of 5.8–17.4 mm. But it is sometimes described in reviews as a 35–105 mm lens, since it has a crop factor of about 6 ("1/2.5-inch" format).[1]

Magnification factor

The crop factor is sometimes referred to as "magnification factor."[2] This usage reflects the observation that lenses of a given focal length seem to produce greater magnification on crop-factor cameras than they do on full-frame cameras. It should be noted that the lens casts the same image no matter what camera it is attached to, and therefore produces the same magnification on all cameras. It is only because the image sensor is smaller in many DSLRs that a narrower FOV is achieved. The end result is that while the lens produces the same magnification it always did, the image produced on small-sensor DSLRs will be enlarged more to produce output (print or screen) that matches the output of a longer focal length lens on a full-frame camera. That is, the magnification as usually defined, from subject to focal plane, is unchanged, but the system magnification from subject to print is increased.

For similar reasons, the crop factor is sometimes referred to as a "focal length factor" or "focal length multiplier".[3]

Secondary effects

When a lens designed for 35 mm format is used on a smaller-format DSLR, besides the obvious reduction in field of view, there may be secondary effects on depth of field, perspective, camera-motion blur, and other photographic parameters.

The depth of field may change, depending on what conditions are compared. Shooting from the same position, with same f-number, but enlarging the image to a given reference size, will yield a reduced depth of field. On the other hand, compared to the 35 mm-equivalent focal length shooting a similarly-framed shot, the smaller camera's depth of field is greater.

Perspective is a property that depends only on viewpoint (camera position). But if moving a lens to a smaller-format camera causes a photographer to move further from the subject, then the perspective will be affected.

The extra amount of enlargement required with smaller-format cameras increases the blur due to defocus, and also increases the blur due to camera motion (shake). As a result, the focal length that can be reliably hand-held at a given shutter speed for a sharp image is reduced by the crop factor. The old rule of thumb that shutter speed should be at least equal to focal length for hand-holding will work equivalently if the actual focal length is multiplied by the FLM first before applying the rule.

Many photographic lenses produce a superior image in the center of the frame than around the edges. When using a lens designed to expose a 35mm film frame with a smaller-format sensor, only the central "sweet spot" of the image is used; a lens that is unacceptably soft or dark around the edges when used in 35mm format may produce acceptable results on a smaller sensor.

See also

References

- ^ Canon SD600 specs. Dpreview.com

- ^ Dan Heller (2007). Digital Travel Photography: Shooting People and Places Like the Pros. Sterling Publishing Co. ISBN 1579909736.

- ^ Tom Ang (2003). Advanced Digital Photography. Amphoto Books. ISBN 0817432736.

External links

- FF vs APS : Real Crop Factor explained. In depth article on the crop factor in digital photography.

- DSLR Crop/Magnification Factor on The Luminous-Landscape

- "Focal Length Multiplier" on Digital Photography Review

- Digital Crop Factor About Lens Multiplication Factors and Apparent Focal Length Increase