Jim Morrison: Difference between revisions

Andrewman327 (talk | contribs) m clean up, typos fixed: november → November, self proclaimed → self-proclaimed using AWB |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

===Films about Morrison=== |

===Films about Morrison=== |

||

[[File:Aydar Akhatov. Jim Morrison - 666. № 1.jpg|right|170px|thumb|Painting by [[Aydar Akhatov]] "Jim Morrison -[[666]]. № 1" (1987): The Demonic image of Morrison]] |

|||

*''[[The Doors (film)|The Doors]]'' (1991), A fiction film by director [[Oliver Stone]], starring [[Val Kilmer]] as Morrison and with cameos by Krieger and Densmore. Kilmer's performance was praised by some critics. [[Ray Manzarek]], The Doors' keyboardist, harshly criticized Stone's portrayal of Morrison, and noted that numerous events depicted in the movie were pure fiction. [[David Crosby]] on an album by [[CPR (band)|CPR]] wrote and recorded a song about the movie with the lyric: ''"And I have seen that movie – and it wasn’t like that – he was mad and lonely – and blind as a bat."''.<ref> |

*''[[The Doors (film)|The Doors]]'' (1991), A fiction film by director [[Oliver Stone]], starring [[Val Kilmer]] as Morrison and with cameos by Krieger and Densmore. Kilmer's performance was praised by some critics. [[Ray Manzarek]], The Doors' keyboardist, harshly criticized Stone's portrayal of Morrison, and noted that numerous events depicted in the movie were pure fiction. [[David Crosby]] on an album by [[CPR (band)|CPR]] wrote and recorded a song about the movie with the lyric: ''"And I have seen that movie – and it wasn’t like that – he was mad and lonely – and blind as a bat."''.<ref>[http://www.sing365.com/music/lyric.nsf/Morrison-lyrics-David-Crosby/D9CF2701F7AE98FA48257011000CFC9C Sing365.com: David Crosby - Morrison Lyrics]</ref> |

||

== Fine art == |

|||

In 1987, the Russian artist [[Aydar Akhatov]] (Russian: Айдар Габдулхаевич Ахатов) painted Jim Morrison in a demonic image of the [[prophet]]-musician, whose life and work have been penetrated by intrusions of [[mysticism]] ([[triptych]] of the paintings of different colors).<ref>[http://www.art-new.ru/photo/7 Gallery of paintings by Aydar Akhatov]</ref><ref>[http://www.people.su/76788_3 Jim Morrison: Biographie]</ref><ref>[http://magneto.elizovo.ru/persona.php?type=show&code=1676 Magneto / Jim Morrison]</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 01:12, 17 May 2013

Jim Morrison | |

|---|---|

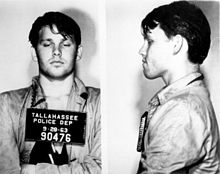

Jim Morrison in 1969 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Douglas Morrison |

| Also known as | The Lizard King, Mr. Mojo Risin' (anagram of "Jim Morrison") |

| Born | December 8, 1943 Melbourne, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | July 3, 1971 (aged 27) Paris, France |

| Genres | Psychedelic rock, blues rock, rock and roll, poetry |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, poet |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, maracas, tambourine, piano, harmonica |

| Years active | 1965–1971 |

| Labels | Elektra, Columbia |

| Website | thedoors.com |

James Douglas "Jim" Morrison (December 8, 1943 – July 3, 1971) was an American singer-songwriter and poet, best remembered as the lead singer of Los Angeles rock band The Doors.[1] From a young age, Morrison developed an alcohol dependency which led to his death at the age of 27 in Paris. He is alleged to have died of a heroin overdose, but as no autopsy was performed, the exact cause of his death is still disputed, as well as rumors floating of him faking his own death to escape the pressures of fame.[2] Morrison was well known for often improvising spoken word poetry passages while the band played live. Due to his wild personality and performances, he is regarded by critics and fans as one of the most iconic, charismatic, and pioneering frontmen in rock music history.[3] Morrison was ranked number 47 on Rolling Stone's list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time",[4] and number 22 on Classic Rock Magazine's "50 Greatest Singers In Rock".[5] Morrison was known as the self-proclaimed "King of Orgasmic Rock".[6]

Early years

James Douglas Morrison was born in Melbourne, Florida, the son of Clara Virginia (née Clarke) and future Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison.[7] Morrison had a sister, Anne Robin, who was born in 1947 in Albuquerque, New Mexico; and a brother, Andrew Lee Morrison, who was born in 1948 in Los Altos, California. His ancestry included English, Scottish, and Irish.[8][9] In 1947, Morrison, then four years old, allegedly witnessed a car accident in the desert, in which a family of Native Americans were injured and possibly killed. He referred to this incident in a spoken word performance on the song "Dawn's Highway" from the album An American Prayer, and again in the songs "Peace Frog" and "Ghost Song". Morrison believed this incident to be the most formative event of his life,[10] and made repeated references to it in the imagery in his songs, poems, and interviews. His family does not recall this incident happening in the way he told it. According to the Morrison biography No One Here Gets Out Alive, Morrison's family did drive past a car accident on an Indian reservation when he was a child, and he was very upset by it. The book The Doors, written by the remaining members of The Doors, explains how different Morrison's account of the incident was from that of his father. This book quotes his father as saying, "We went by several Indians. It did make an impression on him [the young James]. He always thought about that crying Indian." This is contrasted sharply with Morrison's tale of "Indians scattered all over the highway, bleeding to death." In the same book, his sister is quoted as saying, "He enjoyed telling that story and exaggerating it. He said he saw a dead Indian by the side of the road, and I don't even know if that's true."[citation needed]

With his father in the United States Navy, Morrison's family moved often. He spent part of his childhood in San Diego. While his father was stationed at NAS Kingsville, he attended Flato Elementary in Kingsville, Texas.[citation needed] In 1958, Morrison attended Alameda High School in Alameda, California. He graduated from George Washington High School (now George Washington Middle School) in Alexandria, Virginia in June 1961.[citation needed] His father was also stationed at Mayport Naval Air Station in Jacksonville, Florida.[citation needed] Morrison was inspired by the writings of philosophers and poets. He was influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, whose views on aesthetics, morality, and the Apollonian and Dionysian duality would appear in his conversation, poetry and songs.[citation needed] He read Plutarch’s "Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans". He read the works of the French Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, whose style would later influence the form of Morrison’s short prose poems.[citation needed] He was influenced by Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Charles Baudelaire, Molière, and Franz Kafka.[citation needed] Honoré de Balzac and Jean Cocteau, along with most of the French existentialist philosophers.[citation needed] His senior-year English teacher said, "Jim read as much and probably more than any student in class, but everything he read was so offbeat I had another teacher, who was going to the Library of Congress, check to see if the books Jim was reporting on actually existed. I suspected he was making them up, as they were English books on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century demonology. I’d never heard of them, but they existed, and I’m convinced from the paper he wrote that he read them, and the Library of Congress would’ve been the only source."[11] Morrison went to live with his paternal grandparents in Clearwater, Florida, where he attended classes at St. Petersburg College (then known as a junior college). In 1962, he transferred to Florida State University (FSU) in Tallahassee, where he appeared in a school recruitment film.[12] While attending FSU, Morrison was arrested for a prank, following a home football game.[13]

In January 1964, Morrison moved to Los Angeles to attend the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He enrolled in Jack Hirschman's class on Antonin Artaud in the Comparative Literature program within the UCLA English Department. Artaud's brand of surrealist theatre had a profound impact on Morrison's dark poetic sensibility of cinematic theatricality.[citation needed] Morrison completed his undergraduate degree at UCLA's film school within the Theater Arts department of the College of Fine Arts in 1965. He never went to the graduation ceremony, instead having his degree diploma mailed to him.[citation needed] He made several short films while attending UCLA. First Love, the first of these films, made with Morrison's classmate and roommate Max Schwartz, was released to the public when it appeared in a documentary about the film Obscura. During these years, while living in Venice Beach, he became friends with writers at the Los Angeles Free Press. Morrison was an advocate of the underground newspaper until his death in 1971. He later conducted a lengthy and in-depth interview with Bob Chorush and Andy Kent, both working for the Free Press at the time (January 1971), and was planning on visiting the headquarters of the busy newspaper shortly before leaving for Paris.[14]

The Doors

In the summer of 1965, after graduating with a degree from the UCLA film school, Morrison led a bohemian lifestyle in Venice Beach. Living on the rooftop of a building inhabited by his old UCLA cinematography friend, Dennis Jakobs, he wrote the lyrics of many of the early songs the Doors would later perform live and record on albums, the most notable being "Moonlight Drive" and "Hello, I Love You".[citation needed] According to Jakobs, he lived on canned beans and LSD for several months.[citation needed] Morrison and fellow UCLA student, Ray Manzarek, were the first two members of the Doors, forming the group during that same summer of 1965. They had previously met months earlier as fellow cinematography students. The now-legendary story claims that Manzarek was lying on the beach at Venice one day, where he accidentally encountered Morrison.[citation needed] He was impressed with Morrison's poetic lyrics, claiming that they were "rock group" material. Subsequently, drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger joined. Krieger auditioned at Densmore's recommendation and was then added to the lineup. All three musicians shared a common interest in the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's meditation practices at the time, attending scheduled classes, but Morrison was not involved in this series of classes, claiming later that he "did not meditate".[citation needed]

The Doors took their name from the title of Aldous Huxley's book The Doors of Perception (a reference to the unlocking of doors of perception through psychedelic drug use). Huxley's own title was a quotation from William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which Blake wrote: "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite." Although Morrison was known as the lyricist of the group, Krieger also made significant lyrical contributions, writing or co-writing some of the group's biggest hits, including "Light My Fire", "Love Me Two Times", "Love Her Madly", and "Touch Me".[15] On the other hand, Morrison, who didn't write most songs using an instrument, would come up with vocal melodies for his own lyrics, with the other band members contributing chords and rhythm nor did he play an instrument live (except for maracas and tambourine for most shows, and harmonica on a few occasions) or in the studio (excluding maracas, tambourine, handclaps, and whistling). However, he did play the grand piano on "Orange County Suite" and a Moog synthesizer on "Strange Days". In June 1966, Morrison and the Doors were the opening act at the Whisky a Go Go on the last week of the residency of Van Morrison's band Them.[16] Van's influence on Jim's developing stage performance was later noted by John Densmore in his book Riders On The Storm: "Jim Morrison learned quickly from his near-namesake's stagecraft, his apparent recklessness, his air of subdued menace, the way he would improvise poetry to a rock beat, even his habit of crouching down by the bass drum during instrumental breaks."[17] On the final night, the two Morrisons and their two bands jammed together on "Gloria".[18][19][20] In November 1966, Morrison and the Doors produced a promotional film for "Break on Through (To the Other Side)", which was their first single release. The video featured the four members of the group playing the song on a darkened set with alternating views and close-ups of the performers while Morrison lip-synched the lyrics. Morrison and the Doors continued to make music videos, including "The Unknown Soldier", "Moonlight Drive", and "People Are Strange".

The Doors achieved national recognition after signing with Elektra Records in 1967.[21] The single "Light My Fire" spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in July/August 1967.[22] Later, the Doors appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, a popular Sunday night variety series that had introduced the Beatles and Elvis Presley to the United States. Ed Sullivan requested two songs from the Doors for the show, "People Are Strange" and "Light My Fire". Sullivan's censors insisted that the Doors change the lyrics of the song "Light My Fire" from "Girl we couldn't get much higher" to "Girl we couldn't get much better" for the television viewers; this was reportedly due to what was perceived as a reference to drugs in the original lyrics. After giving assurances of compliance to the producer in the dressing room, Morrison told the band "we're not changing a word" and proceeded to sing the song with the original lyrics. Sullivan was not happy and he refused to shake hands with Morrison or any other band member after their performance. He had a show producer tell the band that they will never do The Ed Sullivan Show again. Morrison reportedly said to the producer, in a defiant tone, "Hey man. We just did the Sullivan Show!"[23]

By the release of their second album, Strange Days, the Doors had become one of the most popular rock bands in the United States. Their blend of blues and dark rock tinged with psychedelia included a number of original songs and distinctive cover versions, such as their rendition of "Alabama Song", from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's opera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. The band also performed a number of extended concept works, including the songs "The End", "When the Music's Over", and "Celebration of the Lizard". In 1966, photographer Joel Brodsky took a series of black-and-white photos of Morrison, in a photo shoot known as "The Young Lion" photo session. These photographs are considered among the most iconic images of Jim Morrison and are frequently used as covers for compilation albums, books, and other memorabilia of the Doors and Morrison.[24][25] In 1968, the Doors released their third studio album, Waiting for the Sun. The band performed on July 5 at the Hollywood Bowl, this performance became famous with the DVD: Live at the Hollywood Bowl. It's also this year that the band played, for the first time, in Europe. Their fourth album, The Soft Parade, was released in 1969. It was the first album where the individual band members were given credit on the inner sleeve for the songs they had written. Previously, each song on their albums had been credited simply to "The Doors". On September 6 and 7, 1968, the Doors played four performances at The Roundhouse, London, England with Jefferson Airplane which were filmed by Granada for a television documentary "The Doors are Open" directed by John Sheppard. Around this time, Morrison—who had long been a heavy drinker—started showing up for recording sessions visibly inebriated.[citation needed] He was also frequently late for live performances. As a result, the band would play instrumental music or force Manzarek to take on the singing duties to subdue the impatient audience.

By 1969, the formerly svelte singer had gained weight, grown a beard and mustache, and had begun dressing more casually—abandoning the leather pants and concho belts for slacks, jeans and T-shirts. During a March 1, 1969 concert at the Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami, Morrison attempted to spark a riot in the audience. He failed, but a warrant for his arrest was issued by the Dade County Police department three days later for indecent exposure. Consequently, many of The Doors' scheduled concerts were canceled.[26][27] In September 1970, Morrison was convicted of indecent exposure and profanity.[6] Morrison, who attended the sentencing "in a wool jacket adorned with Indian designs", silently listened as he was sentenced for six months in prison and had to pay a $500 fine.[6] Morrison remained free on a $50,000 bond.[6] At the sentencing, Judge Murray Goodman told Morrison that he was a "person graced with a talent" admired by many of his peers.[6] In 2007 Florida Governor Charlie Crist suggested the possibility of a posthumous pardon for Morrison, which was announced as successful on December 9, 2010.[28][29] Drummer John Densmore denied Morrison ever exposed himself on stage that night.[30] Following The Soft Parade, The Doors released Morrison Hotel. After a lengthy break the group reconvened in October 1970 to record what would become their final album with Morrison, entitled L.A. Woman. Shortly after the recording sessions for the album began, producer Paul A. Rothchild—who had overseen all of their previous recordings—left the project. Engineer Bruce Botnick took over as producer.

Poetry and film

Morrison began writing in earnest during his adolescence. At UCLA he studied the related fields of theater, film, and cinematography.[31] He self-published two separate volumes of his poetry in 1969, entitled The Lords / Notes on Vision and The New Creatures. The Lords consists primarily of brief descriptions of places, people, events and Morrison's thoughts on cinema. The New Creatures verses are more poetic in structure, feel and appearance. These two books were later combined into a single volume titled The Lords and The New Creatures. These were the only writings published during Morrison's lifetime. Morrison befriended Beat poet Michael McClure, who wrote the afterword for Danny Sugerman's biography of Morrison, No One Here Gets Out Alive. McClure and Morrison reportedly collaborated on a number of unmade film projects, including a film version of McClure's infamous play The Beard, in which Morrison would have played Billy the Kid.[32] After his death, a further two volumes of Morrison's poetry were published. The contents of the books were selected and arranged by Morrison's friend, photographer Frank Lisciandro, and girlfriend Pamela Courson's parents, who owned the rights to his poetry.

The Lost Writings of Jim Morrison Volume I is entitled Wilderness, and, upon its release in 1988, became an instant New York Times Bestseller. Volume II, The American Night, released in 1990, was also a success. Morrison recorded his own poetry in a professional sound studio on two separate occasions. The first was in March 1969 in Los Angeles and the second was on December 8, 1970. The latter recording session was attended by Morrison's personal friends and included a variety of sketch pieces. Some of the segments from the 1969 session were issued on the bootleg album The Lost Paris Tapes and were later used as part of the Doors' An American Prayer album,[33] released in 1978. The album reached No. 54 on the music charts. Some poetry recorded from the December 1970 session remains unreleased to this day and is in the possession of the Courson family. Morrison's best-known but seldom seen cinematic endeavor is HWY: An American Pastoral, a project he started in 1969. Morrison financed the venture and formed his own production company in order to maintain complete control of the project. Paul Ferrara, Frank Lisciandro and Babe Hill assisted with the project. Morrison played the main character, a hitchhiker turned killer/car thief. Morrison asked his friend, composer/pianist Fred Myrow, to select the soundtrack for the film.[34]

Personal life

Morrison's family

Morrison's early life was a nomadic existence typical of military families.[35] Jerry Hopkins recorded Morrison's brother, Andy, explaining that his parents had determined never to use physical corporal punishment such as spanking on their children. They instead instilled discipline and levied punishment by the military tradition known as dressing down. This consisted of yelling at and berating the children until they were reduced to tears and acknowledged their failings. Once Morrison graduated from UCLA, he broke off most contact with his family. By the time Morrison's music ascended to the top of the charts (in 1967) he had not been in communication with his family for more than a year and falsely claimed that his parents and siblings were dead (or claiming, as it has been widely misreported, that he was an only child).

This misinformation was published as part of the materials distributed with The Doors' self-titled debut album. George Morrison was not supportive of his son's career choice in music. One day, an acquaintance brought over a record thought to have Jim on the cover. The record was the Doors self-titled debut. The young man played the record for Morrison's father and family. Upon hearing the record, Morrison's father wrote him a letter telling him "to give up any idea of singing or any connection with a music group because of what I consider to be a complete lack of talent in this direction."[36] In a letter to the Florida Probation and Parole Commission District Office dated October 2, 1970, Morrison's father acknowledged the breakdown in family communications as the result of an argument over his assessment of his son's musical talents. He said he could not blame his son for being reluctant to initiate contact and that he was proud of him nonetheless.[37]

Relationships

Morrison met his long-term companion,[38] Pamela Courson, well before he gained any fame or fortune,[39] and she encouraged him to develop his poetry. At times, Courson used the surname "Morrison" with his apparent consent or at least lack of concern. After Courson's death on April 25, 1974, the probate court in California decided that she and Morrison had what qualified as a common-law marriage (see below, under "Estate Controversy"). Morrison and Courson's relationship was a stormy one, with frequent loud arguments and periods of separation. Biographer Danny Sugerman surmised that part of their difficulties may have stemmed from a conflict between their respective commitments to an open relationship and the consequences of living in such a relationship.

In 1970, Morrison participated in a Celtic Pagan handfasting ceremony with rock critic and science fiction/fantasy author Patricia Kennealy. Before witnesses, one of them a Presbyterian minister,[40] the couple signed a document declaring themselves wed,[41] but none of the necessary paperwork for a legal marriage was filed with the state. Kennealy discussed her experiences with Morrison in her autobiography Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison and in an interview reported in the book Rock Wives.

Morrison also reportedly regularly had sex with fans ("groupies") such as Josépha Karcz who wrote a novel about their night together, and had numerous short flings with females connected with the music business or the print media. They included Nico, the singer associated with The Velvet Underground, a one night stand with singer Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane, an on-again-off-again relationship with 16 Magazine's Gloria Stavers as well as an alleged alcohol-fueled encounter with Janis Joplin. David Crosby said many years later Morrison treated Joplin meanly at a party at the home of John Davidson while Davidson was out of town.[42][43] She allegedly attacked him with a bottle of booze in front of witnesses, and that ended their only encounter.[42][43] Alice Cooper declared on his syndicated radio show that Morrison was scrupulously true to Pamela on tour, eschewing all sexual encounters.[citation needed] Linda Ashcroft, in her book, Wild Child: My Life With Jim Morrison details her life with Morrison as well. Judy Huddleston also recalls her relationship with Morrison in This is The End...My Only Friend: Living and Dying with Jim Morrison. At the time of his death there were as many as twenty paternity actions pending against him, although no claims were made against his estate by any of the putative paternity claimants.

Death

Morrison joined Courson in Paris in March 1971. They took up residence in the city in a rented apartment on the rue Beautreillis (in the 4th arrondissement of Paris on the Right Bank), and went for long walks throughout the city,[44] admiring the city's architecture. During this time, Morrison shaved his beard and lost some of the weight he had gained in the previous months.[45] His last studio recording was with two American street musicians—a session dismissed by Manzarek as "drunken gibberish".[46] The session included a version of a song-in-progress, "Orange County Suite", which can be heard on the bootleg The Lost Paris Tapes. Morrison died on July 3, 1971 at age 27.[47] In the official account of his death, he was found in a Paris apartment bathtub (at 17–19 rue Beautreillis, 4th arrondissement) by Courson.[48] Pursuant to French law, no autopsy was performed because the medical examiner stated that there was no evidence of foul play.[48] The absence of an official autopsy has left many questions regarding Morrison's cause of death.[2] In Wonderland Avenue, Danny Sugerman discussed his encounter with Courson after she returned to the United States. According to Sugerman's account, Courson stated that Morrison had died of a heroin overdose, having inhaled what he believed to be cocaine. Sugerman added that Courson had given him numerous contradictory versions of Morrison's death, saying at times that she had killed Morrison, or that his death was her fault. Courson's story of Morrison's unintentional ingestion of heroin, followed by his accidental overdose, is supported by the confession of Alain Ronay, who has written that Morrison died of a hemorrhage after snorting Courson's heroin, and that Courson nodded off instead of phoning for medical help, leaving Morrison bleeding to death.[49]

Ronay confessed in an article in Paris that he then helped cover up the circumstances of Morrison's death.[50] In the epilogue of No One Here Gets Out Alive, Hopkins and Sugerman write that Ronay and Agnès Varda say Courson lied to the police who responded to the death scene, and later in her deposition, telling them Morrison never took drugs. In the epilogue to No One Here Gets Out Alive, Hopkins says that 20 years after Morrison's death, Ronay and Varda broke their silence and gave this account: They arrived at the house shortly after Morrison's death and Courson said that she and Morrison had taken heroin after a night of drinking. Morrison had been coughing badly, had gone to take a bath, and vomited blood. Courson said that he appeared to recover and that she then went to sleep. When she awoke sometime later Morrison was unresponsive, so she called for medical assistance. Hopkins and Sugerman also claim that Morrison had asthma and was suffering from a respiratory condition involving a chronic cough and vomiting blood on the night of his death. This theory is partially supported in The Doors (written by the remaining members of the band) in which they claim Morrison had been coughing up blood for nearly two months in Paris, but none of the members of The Doors were in Paris with Morrison in the months prior to his death. According to a Madame Colinette, who was at the cemetery that day mourning the recent loss of her husband, she witnessed Morrison's funeral at Père Lachaise Cemetery.[51] The ceremony was "pitiful", with several of the attendants muttering a few words, throwing flowers over the casket, then leaving quickly and hastily within minutes as if their lives depended upon it.[51] Those who attended included Alain Ronay, Agnes Varda, Bill Siddons (manager), Courson, and Robin Wertle (Morrison's Canadian private secretary at the time for a few months).[51] In the first version of No One Here Gets Out Alive, published in 1980, Sugerman and Hopkins gave some credence to the rumor that Morrison may not have died at all, calling the fake death theory “not as far-fetched as it might seem”.[52] This theory led to considerable distress for Morrison's loved ones over the years, notably when fans would stalk them, searching for evidence of Morrison's whereabouts.[53][54]

In 1995, a new epilogue was added to Sugerman's and Hopkins's book, giving new facts about Morrison's death and discounting the fake death theory saying, “As time passed, some of Jim and Pamela [Courson]'s friends began to talk about what they knew, and although everything they said pointed irrefutably to Jim's demise, there remained and probably always will be those who refuse to believe that Jim is dead and those who will not allow him to rest in peace.”[55] In July 2007, Sam Bernett, a former manager of the Rock 'n' Roll Circus nightclub, released a (French) book titled "The End: Jim Morrison".[48][56][57] In it Bernett alleges that instead of dying of a heart attack in a bathtub (the official police version of his death) Morrison overdosed on heroin on a toilet seat in the nightclub. He claims that Morrison came to the club to buy heroin for Courson then did some himself and died in the bathroom.[57] Morrison's body was then moved back to his rue Beautreillis apartment and dumped into the bathtub by the two drug dealers from whom Morrison had purchased the heroin.[57] Bernett says those who saw Morrison that night were sworn to secrecy in order to prevent a scandal for the famous club,[58] and that some of the witnesses immediately left the country. There have been many other conspiracy theories surrounding Morrison's death[59][60] but are less supported by witnesses than are the accounts of Ronay and Courson.[61]

Grave site

Morrison is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, one of the city's most visited tourist attractions. The grave had no official marker until French officials placed a shield over it, which was stolen in 1973. The site previous to the 1973 theft (pictured, right) was covered with shells and letters. In 1981, Croatian sculptor Mladen Mikulin[62] placed a bust of Morrison and a new gravestone with Morrison's name at the grave to commemorate the 10th anniversary of his death; the bust was defaced through the years by cemetery vandals and later stolen in 1988.[63] Mikulin later made two more portraits of Jim Morrison: the plaster model for (never finished) bronze bust in 1989,[64] and the bronze death mask in 2001.[65] In the early 1990s Morrison's father George Stephen Morrison, after consulting with E. Nicholas Genovese, Professor Emeritus of Classics, Ancient Greek and Latin languages at San Diego State University, placed a flat stone on the grave. The stone bears the Greek inscription: ΚΑΤΑ ΤΟΝ ΔΑΙΜΟΝΑ ΕΑΥΤΟΥ, literally meaning "according to his own daemon" and usually interpreted as "true to his own spirit".[66][67][68]

Estate controversy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2012) |

In his last will, notarized in Los Angeles on February 12, 1969, Morrison (who described himself as "an unmarried person") bequeathed his entire estate to Pamela Courson, naming her co-executor with his attorney, Max Fink.[citation needed] Subsequently, she inherited everything upon Morrison’s death.[citation needed] Courson died of a heroin overdose in 1974, leaving her parents as her heirs.[citation needed] Like Morrison, she was also 27 years old at the time of her death.[69] Morrison's parents then contested Morrison's will.[citation needed] Courson's parents then produced a document they claimed she had acquired in Colorado, an application for a declaration that she and Morrison had contracted a common-law marriage under the law of that state.[citation needed] Courson, as Morrison's spouse, would inherit even if the will was invalid.[citation needed] The ability to contract a common-law marriage was abolished in California in 1896.[citation needed] However, California's conflict of laws rule provided for recognition of common-law marriages when lawfully contracted in foreign jurisdictions,[citation needed] and Colorado recognizes common-law marriage.[70]

Artistic influences

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2012) |

As a naval family the Morrisons relocated frequently. Consequently Morrison's early education was routinely disrupted as he moved from school to school. Nonetheless he was drawn to the study of literature, poetry, religion, philosophy and psychology, among other fields.[citation needed] Biographers have consistently pointed to a number of writers and philosophers who influenced Morrison's thinking and, perhaps, his behavior.[citation needed] While still in his teens Morrison discovered the work of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.[citation needed] He was also drawn to the poetry of William Blake, Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud.[citation needed] Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac also had a strong influence on Morrison's outlook and manner of expression; Morrison was eager to experience the life described in Kerouac's On the Road.[citation needed] He was similarly drawn to the work of French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline.[citation needed] Céline's book, Voyage au Bout de la Nuit (Journey to the End of the Night) and Blake's Auguries of Innocence both echo through one of Morrison's early songs, "End of the Night".[citation needed] Morrison later met and befriended Michael McClure, a well known beat poet. McClure had enjoyed Morrison's lyrics but was even more impressed by his poetry and encouraged him to further develop his craft.[citation needed] Morrison's vision of performance was colored by the works of 20th century French playwright Antonin Artaud (author of Theater and its Double) and by Julian Beck's Living Theater.[citation needed]

Other works relating to religion, mysticism, ancient myth and symbolism were of lasting interest, particularly Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces. James Frazer's The Golden Bough also became a source of inspiration and is reflected in the title and lyrics of the song "Not to Touch the Earth".[citation needed] Morrison was particularly attracted to the myths and religions of Native American cultures.[71] While he was still in school, his family moved to New Mexico where he got to see some of the places and artifacts important to the American Southwest indigenous cultures. These interests appear to be the source of many references to creatures and places such as lizards, snakes, deserts and "ancient lakes" that appear in his songs and poetry. His interpretation of the practices of a Native American "shaman" were worked into parts of Morrison's stage routine, notably in his interpretation of the Ghost Dance, and a song on his later poetry album, The Ghost Song. Jim Morrison's vocal influences included Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra, which is evident in his own baritone crooning style used in several of The Doors songs and in the 1981 documentary The Doors: A Tribute to Jim Morrison, Producer Paul Rothchild refers his first impression of Morrison as being a "Rock and Roll Bing Crosby". It is mentioned within the pages of No One Here Gets Out Alive by Danny Sugerman, that Morrison as a teenager was such a fan of Presley's music that he demanded people be quiet when Elvis was on the radio. The Frank Sinatra influence is mentioned in the pages of The Doors, The Illustrated History also by Sugerman, where Frank Sinatra is listed on Morrison's Band Bio as being his favorite singer. Reference to this can also be found in a Rolling Stone article about Jim Morrison, regarding the Top 100 rock singers of all time.[72]

Legacy

Morrison was, and continues to be, one of the most popular and influential singer-songwriters in rock history. The Doors' catalog has become an unequivocal staple of classic rock radio stations. To this day Morrison is widely regarded as the prototypical rock-star: surly, sexy, scandalous, and mysterious.[73] The leather pants he was fond of wearing both onstage and off have since become stereotyped as rock-star apparel.[74] In 2011, a Rolling Stone readers' pick placed Jim Morrison in fifth place of the magazine's "Best Lead Singers of All Time".[75] Iggy and the Stooges are said to have formed after lead singer Iggy Pop was inspired by Morrison while attending a Doors concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[76] One of Pop's most popular songs, "The Passenger", is said to be based on one of Morrison's poems.[77] After Morrison's death, Pop was considered as a replacement lead singer for The Doors; the surviving Doors gave him some of Morrison's belongings and hired him as a vocalist for a series of shows. Wallace Fowlie, professor emeritus of French literature at Duke University, wrote Rimbaud and Jim Morrison, subtitled "The Rebel as Poet – A Memoir". In this he recounts his surprise at receiving a fan letter from Morrison who, in 1968, thanked him for his latest translation of Arthur Rimbaud's verse into English. "I don't read French easily", he wrote, "...your book travels around with me." Fowlie went on to give lectures on numerous campuses comparing the lives, philosophies and poetry of Morrison and Rimbaud.

Layne Staley, the late vocalist of Alice in Chains, Scott Weiland, the vocalist of Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver, Julian Casablancas of The Strokes, James LaBrie of Dream Theater, as well as Scott Stapp of Creed, have all claimed Morrison to be their biggest influence and inspiration. Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver have both covered "Roadhouse Blues" by The Doors. Weiland also filled in for Morrison to perform "Break On Through (To The Other Side)" with the rest of The Doors. Stapp filled in for Morrison for "Light My Fire", "Riders on the Storm" and "Roadhouse Blues" on VH1 Storytellers. Creed performed their version of "Roadhouse Blues" with Robby Krieger for the 1999 Woodstock Festival. The book The Doors by the remaining Doors quotes Morrison's close friend Frank Lisciandro as saying that too many people took a remark of Morrison's that he was interested in revolt, disorder, and chaos “to mean that he was an anarchist, a revolutionary, or, worse yet, a nihilist. Hardly anyone noticed that Jim was restating Rimbaud and the Surreal poets.”[78] Jim's recital of his poem "Bird Of Prey" can be heard throughout the song "Sunset" by Fatboy Slim. Rock band Bon Jovi featured Morrison's grave in their "I'll Sleep When I'm Dead" video clip. Professional wrestler John Hennigan's persona John Morrison was inspired by Jim Morrison, and the name of his finishing move was taken from The Doors' Moonlight Drive. The band Radiohead mentions Jim Morrison in their song "Anyone Can Play Guitar", stating "I wanna be wanna be wanna be Jim Morrison". Singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey mentions Jim Morrison in the song "Gods & Monsters" from the album "Born To Die: Paradise Edition". Alice Cooper in the liner notes of the album Killer stated that the song "Desperado" is about Jim Morrison. The leather pants of U2's Bono's "The Fly" persona for the Achtung Baby era and subsequent Zoo TV Tour is attributed to Jim Morrison.

Discography

The Doors

- The Doors (1967)

- Strange Days (1967)

- Waiting for the Sun (1968)

- The Soft Parade (1969)

- Absolutely Live (1970)

- Morrison Hotel (1970)

- L.A. Woman (1971)

- An American Prayer (1978)

Books

By Morrison

- The Lords and the New Creatures (1969). 1985 edition: ISBN 0-7119-0552-5

- An American Prayer (1970) privately printed by Western Lithographers. (Unauthorized edition also published in 1983, Zeppelin Publishing Company, ISBN 0-915628-46-5. The authenticity of the unauthorized edition has been disputed.)

- Wilderness: The Lost Writings Of Jim Morrison (1988). 1990 edition: ISBN 0-14-011910-8

- The American Night: The Writings of Jim Morrison (1990). 1991 edition: ISBN 0-670-83772-5

About Morrison

- Dylan Jones, Jim Morrison: Dark Star, (1990) ISBN 0-7475-0951-4

- Linda Ashcroft, Wild Child: Life with Jim Morrison, (1997) ISBN 1-56025-249-9

- Lester Bangs, "Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later" in Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, John Morthland, ed. Anchor Press (2003) ISBN 0-375-71367-0

- Stephen Davis, Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend, (2004) ISBN 1-59240-064-7

- John Densmore, Riders on the Storm: My Life With Jim Morrison and the Doors (1991) ISBN 0-385-30447-1

- Dave DiMartino, Moonlight Drive (1995) ISBN 1-886894-21-3

- Wallace Fowlie, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison (1994) ISBN 0-8223-1442-8

- Jerry Hopkins, The Lizard King: The Essential Jim Morrison (1995) ISBN 0-684-81866-3

- Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980) ISBN 0-85965-138-X

- Patricia Kennealy, Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison (1992) ISBN 0-525-93419-7

- Gerry Kirstein, "Some Are Born to Endless Night: Jim Morrison, Visions of Apocalypse and Transcendence" (2012) ISBN 1451558066

- Frank Lisciandro, Morrison: A Feast of Friends (1991) ISBN 0-446-39276-6, Morrison — Un festin entre amis (1996) (French)

- Frank Lisciandro, Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic (A Photojournal) (1982) ISBN 0-85965-246-7, James Douglas Morrison (2005) (French)

- Ray Manzarek, Light My Fire (1998) ISBN 0-446-60228-0L. First by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman (1981)

- Peter Jan Margry, The Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison's Grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery: The Social Construction of Sacred Space. In idem (ed.), Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World. New Itineraries into the Sacred. Amsterdam University Press, 2008, p. 145–173.

- Thanasis Michos, The Poetry of James Douglas Morrison (2001) ISBN 960-7748-23-9 (Greek)

- Daveth Milton, We Want The World: Jim Morrison, The Living Theatre, and the FBI, (2012) ISBN 978-0957051188

- Mark Opsasnick, The Lizard King Was Here: The Life and Times of Jim Morrison in Alexandria, Virginia (2006) ISBN 1-4257-1330-0

- James Riordan & Jerry Prochnicky, Break on through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison (1991) ISBN 0-688-11915-8

- Adriana Rubio, Jim Morrison: Ceremony...Exploring the Shaman Possession (2005) ISBN

- The Doors (remaining members Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore) with Ben Fong-Torres, The Doors (2006) ISBN 1-4013-0303-X

Films

Documentaries featuring Morrison

- The Doors Are Open (1968)

- Live in Europe (1968)

- Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1968)

- Feast of Friends (1970)

- The Doors: A Tribute to Jim Morrison (1981)

- The Doors: Dance on Fire (1985)

- The Soft Parade, a Retrospective (1991)

- Final 24: Jim Morrison (2007), The Biography Channel[79]

- The Doors: No One Here Gets Out Alive (2009)

- When You're Strange (2009)

- Morrison's Mustang – A Vision Quest to Find The Blue Lady (2011, in production)

- Mr. Mojo Risin': The Story of L.A. Woman (2012)

Films about Morrison

- The Doors (1991), A fiction film by director Oliver Stone, starring Val Kilmer as Morrison and with cameos by Krieger and Densmore. Kilmer's performance was praised by some critics. Ray Manzarek, The Doors' keyboardist, harshly criticized Stone's portrayal of Morrison, and noted that numerous events depicted in the movie were pure fiction. David Crosby on an album by CPR wrote and recorded a song about the movie with the lyric: "And I have seen that movie – and it wasn’t like that – he was mad and lonely – and blind as a bat.".[80]

Fine art

In 1987, the Russian artist Aydar Akhatov (Russian: Айдар Габдулхаевич Ахатов) painted Jim Morrison in a demonic image of the prophet-musician, whose life and work have been penetrated by intrusions of mysticism (triptych of the paintings of different colors).[81][82][83]

References

- ^ "See e.g., Morrison poem backs climate plea", BBC News, January 31, 2007.

- ^ a b Doland, Angela (November 11, 2007). "New questions about Jim Morrison's death". Associated Press Writer Verena von Derschau in Paris contributed to this report. USA Today. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ Steve Huey. Jim Morrison: Biography. Allmusic.

- ^ "100 Greatest Singers: Jim Morrison". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ May 2009. Classic Rock Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e "Rock Singer Sentenced". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. October 30, 1970. p. 15. Retrieved 05-07-2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ http://ivbc.free.fr/AA-Histoire-9999-99-96.htm

- ^ "Dead Famous: Jim Morrison." The Biography Channel. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ http://mg.co.za/article/2003-09-01-riding-the-storm-again-without-morrison

- ^ Davis, Stephen (2004). Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. Ebury Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-09-190042-7.

It was the first time I discovered death, he recounted many years later, as the tape rolled in a darkened West Hollywood Recording studio.

- ^ Hopkins (1980). No One Here Gets Out Alive. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-69733-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Florida State University: Toward a Greater University". Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "FSU Arrest". Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn. "Criticism Lighting His Fire: Perspectives on Jim Morrison from the Los Angeles Free Press, Down Beat, The Miami Herald (master's thesis, Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts, Louisiana State University, 2007). Available at "http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-11162007-105056/."

- ^ Getlen, Larry. "Opportunity Knocked So The Doors Kicked It Down". Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Lawrence, Paul (2002). "The Doors and Them: Twin Morrisons of Different Mothers". waiting-forthe-sun.net. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hinton (1997), page 67.

- ^ Corry Arnold (January 23, 2006). "The History of the Whisky-A-Go-Go". chickenonaunicyle.com. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ^ "Glossary entry for The Doors". Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. from Van Morrison website. Photo of both Morrisons on stage. Access date 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Doors 1966 – June 1966". doorshistory.com. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (April 20, 2007). "Confessions of a Record Label Owner". CNN. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "Billboard.com – Hot 100 – Week of August 12, 1967". Billboard. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Doors". The Ed Sullivan Show (SOFA Entertainment). Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ "Album photographer Joel Brodsky dies – Arts & Entertainment". CBC News. April 2, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "Photographer Brodsky dies". Sun Journal. April 1, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Doors: Biography: Rolling Stone". Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[dead link] - ^ Perpetua, Matthew (December 23, 2010). "The Doors Not Satisfied With Morrison Pardon, Want Formal Apology". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "Fla. officials pardon the late Jim Morrison". Miami Herald. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Florida pardons Doors' Jim Morrison". Reuters. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Drummer says Jim Morrison never exposed himself". Reuters. December 2, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Notable Actors – UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television". Retrieved December 3, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ McClure, Michael. "Michael McClure Recalls an Old Friend". Retrieved September 9, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Morrison, Jim. "American Prayer: Jim Morrison & The Doors: Music". Amazon.com. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Liner Notes for Diane Hildebrand's "Early Morning Blues and Greens". Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Jim Morrison Biography". Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ Soeder, John (May 20, 2007). "Love Them Two Times". Plain Dealer. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ "Letter from Jim's Father to probation department 1970". Idafan.com. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ Hoover, Elizabeth D. (July 3, 2006). "The Death of Jim Morrison". American Heritage. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Jim Morrison Biography". Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ Kennealy, Patricia (1992). Strange Days: My Life With And Without Jim Morrison. New York: Dutton/Penguin. p. 63. ISBN 0-525-93419-7.

- ^ Kennealy (1992) plate 7, p.175

- ^ a b People Weekly citation of 1988 book "Long Time gone" by David Crosby and Carl Gottlieb

- ^ a b Los Angeles Times reference to Morrison/Joplin fight mentioned in #2 Barney's Beanery

- ^ Kennealy (1992) pp.314–16

- ^ Davis, Steven (2004) "The Last Days of Jim Morrison". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- ^ Transcript (April 10, 2002). "Ask Ray Manzarek Transcript". Talk. BBC. Accessed November 18, 2010.

- ^ United Press International (July 9, 1971). "Jim Morrison: Lead rock singer dies in Paris". The Toronto Star. Toronto. UPI. p. 26.

- ^ a b c http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-466947/The-shocking-truth-pal-Jim-Morrison-REALLY-died.html

- ^ Ronay, Alain (2002). "Jim and I – Friends until Death". Originally published in King. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- ^ Kennealy (1992) pp: 385–392 quotes from Ronay's interview in Paris Match.

- ^ a b c http://forum.johndensmore.com/index.php?showtopic=2446

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny. No One Here Gets Out Alive. pg. 373.

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny (1980). No One Here Gets Out Alive. ISBN 0-85965-138-X.

- ^ Kennealy (1992) pp.344–346

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny. No One Here Gets Out Alive pg. 375; also see copyright in front of book on new material added in 1995.

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/THE-END-JIM-MORRISON-Bernett/dp/2350760529

- ^ a b c http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/19714635/ns/today-books/t/did-jim-morrison-really-die-his-bathtub/#.UAiP4bRI98E

- ^ Walt, Vivienne. "How Jim Morrison Died". Time. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ "The shocking truth about Jim Morrison's death surfaces". AndhraNews.net story, July 8, 2007.

- ^ "The Shocking Truth about How My Pal Jim Morrison Really Died". mailonsunday.co.uk. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ^ Doland, Angela. "Morrison Bathtub Death Story Questioned". Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Mladen Mikulin – sculptor". Ars-cartae.com. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ Photo of defaced bust on Morrison's grave before it was stolen.

- ^ "Mladen Mikulin – The Plaster Model of Jim Morrison, 1989". M. E. Lukšić. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ "Mislav E. Lukšić – 'Mladen Mikulin - the Portraitist of Jim Morrison', 2011". M. E. Lukšić. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ Liewer, Steve (November 28, 2008). "George 'Steve' Morrison; Rear Admiral Flew Combat Missions in Lengthy Career". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Accessed November 18, 2010.

- ^ Davis, Stephen (2005). Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. Gotham. p. 472. ISBN 978-1-59240-099-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Olsen, Brad (2007). Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-888729-12-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?GRid=4355&page=gr

- ^ Marriage license Laws in the state of Colorado

- ^ "Jim Morrison". UXL Newsmakers. 2005. Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ http://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/6027/32782/33583

- ^ Andy Bennett (2004), Remembering Woodstock, Ashgate Publishing, p.52.

- ^ Kurt Hemmer (2007), Encyclopedia of beat literature, Infobase Publishing, p.217.

- ^ Rolling Stone Readers Pick the Best Lead Singers of All Time (5.Jim Morrison). Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 5, 2011

- ^ "The Stooges: Biography: Rolling Stone". Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Webb, Robert. "ROCK & POP: STORY OF THE SONG – 'THE PASSENGER' Iggy Pop (1977)". Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ The Doors (remaining members Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore) with Ben Fong-Torres, The Doors, page 104

- ^ "Biography Channel documentary". Biography.com. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ Sing365.com: David Crosby - Morrison Lyrics

- ^ Gallery of paintings by Aydar Akhatov

- ^ Jim Morrison: Biographie

- ^ Magneto / Jim Morrison

External links

- 1943 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century American actors

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century American writers

- 20th-century poets

- American baritones

- American expatriates in France

- American male film actors

- American male singer-songwriters

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American poets

- American rock singer-songwriters

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Florida State University alumni

- Military brats

- Obscenity controversies

- People from Melbourne, Florida

- Psychedelic drug advocates

- Recipients of American gubernatorial pardons

- Singers from Florida

- Songwriters from Florida

- The Doors members

- UCLA Film School alumni

- University of California, Los Angeles alumni

- Writers from Florida