People's Liberation Army Rocket Force: Difference between revisions

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

=== Intercontinental ballistic missiles === |

=== Intercontinental ballistic missiles === |

||

<ref>{{cite web |title = Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces |url = https://fas.org/blogs/security/2016/05/chinareport2016/ |publisher = Federation of American Scientists }}</ref> |

<ref>{{cite web |title = Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces |url = https://fas.org/blogs/security/2016/05/chinareport2016/ |publisher = Federation of American Scientists }}</ref> |

||

* [[DF-41]] - 10~20(deployed) |

* [[DF-41]] - 10~20 (deployed) |

||

* [[DF-31#DF-31B|DF-31B]] - 20~30 |

* [[DF-31#DF-31B|DF-31B]] - 20~30 |

||

* [[DF-31#DF-31A|DF-31A]] - 30~50 |

* [[DF-31#DF-31A|DF-31A]] - 30~50 |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

* [[DF-4]] - 20~35 |

* [[DF-4]] - 20~35 |

||

=== Intermediate-range ballistic |

=== Intermediate-range ballistic missiles === |

||

* [[DF-26]] - 80 |

* [[DF-26]] - 80 |

||

Revision as of 05:15, 13 October 2019

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

| People's Liberation Army Rocket Force | |

|---|---|

| 中国人民解放军火箭军 | |

Emblem of the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force | |

| Active | 1966–2015 (Second Artillery Corps) 2016–present (Rocket Force) |

| Land | |

| Allegiance | |

| Typ | Tactical and strategic missile force |

| Role | Strategic deterrence, second strike |

| Size | 100,000 personnel |

| Part of | |

| Hauptsitz | Qinghe, Haidian District, Beijing, China |

| Colors | Red, gold, dark green |

| March | "March of the Rocket Force" (《火箭军进行曲》) |

| Equipment | Ballistic missiles, cruise missiles |

| Engagements | Third Taiwan Strait Crisis |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Lt. General Zhou Yaning |

| Political Commissar | General Wang Jiasheng |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Badge |  |

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF; Chinese: 中国人民解放军火箭军), formerly the Second Artillery Corps (SAC; Chinese: 第二炮兵), is the strategic and tactical missile forces of the People's Republic of China. The PLARF is a component part of the People's Liberation Army and controls the nation's arsenal of land-based ballistic missiles—both (thermo)nuclear and conventional. The military arm was established on 1 July 1966 and made its first public appearance on 1 October 1984. The headquarters for operations is located at Qinghe, Beijing. The PLARF is under the direct command of the Chinese Central Military Commission.

In total, China is estimated to be in possession of 280 nuclear warheads, with an unknown number of them active and ready to deploy.[2] However, as of 2013, United States Intelligence estimates the Chinese active ICBM arsenal to range between 50 and 75 land and sea-based missiles.[3] The PLARF comprises approximately 100,000 personnel and six ballistic missile brigades. The six brigades are independently deployed in different military regions throughout the country. Currently it has 1,833 ballistic missiles and 350 cruise missiles in its arsenal.

The name was changed to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force on 1 January 2016.[4] Several reports have suggested that the PLARF may control the whole triad of China's nuclear missiles, including sea-based ballistic missiles.[5][6]

China has the largest land-based missile arsenal in the world. According to Pentagon estimates, this includes 1,200 conventionally armed short-range ballistic missiles, two hundred to three hundred conventional medium-range ballistic missiles and an unknown number of conventional intermediate-range ballistic missiles, as well as two to three hundred ground-launched cruise missiles. Many of these are extremely accurate, which would allow them to destroy targets even without nuclear warheads.[7]

History

In the late 1980s, China was the world's third-largest nuclear power, possessing a small but credible nuclear deterrent force of approximately 100 to 400 nuclear weapons. Beginning in the late 1970s, China deployed a full range of nuclear weapons and acquired a nuclear second-strike capability. The nuclear forces were operated by the 100,000-person Strategic Missile Force, which was controlled directly by the Joint staff.

China began developing nuclear weapons in the late 1950s with substantial Soviet assistance. With the Sino-Soviet split in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union withheld plans and data for an atomic bomb, abrogated the agreement on transferring defense and nuclear technology, and began the withdrawal of Soviet advisers in 1960. Despite the termination of Soviet assistance, China committed itself to continue nuclear weapons development to break "the superpowers' monopoly on nuclear weapons," to ensure Chinese security against the Soviet and United States threats, and to increase Chinese prestige and power internationally.

China made fast progress in the 1960s in developing nuclear weapons. In a 32-month period, China successfully tested its first atomic bomb on October 16, 1964 at Lop Nor, launched its first nuclear missile on October 25, 1966 and detonated its first hydrogen bomb on June 14, 1967. Deployment of the Dongfeng-1 conventionally armed short-range ballistic missile and the Dongfeng-2 (CSS-1) medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) occurred in the 1960s. The Dongfeng-3 (CCS-2) intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) was successfully tested in 1969. Although the Cultural Revolution disrupted the strategic weapons program less than other scientific and educational sectors in China, there was a slowdown in succeeding years.

Gansu hosted a missile launching area.[8] China destroyed 9 U-2 surveillance craft while two went missing when they attempted to spy on it.[9]

In the 1970s the nuclear weapons program saw the development of MRBM, IRBM and ICBMs and marked the beginning of a deterrent force. China continued MRBM deployment, began deploying the Dongfeng-3 IRBM and successfully tested and commenced deployment of the Dongfeng-4 (CSS-4) limited-range ICBM.

By 1980 China had overcome the slowdown in nuclear development caused by the Cultural Revolution and had successes in its strategic weapons program. In 1980 China successfully test launched its full-range ICBM, the Dongfeng-5 (CCS-4); the missile flew from central China to the Western Pacific, where it was recovered by a naval task force. The Dongfeng-5 possessed the capability to hit targets in the western Soviet Union and the United States. In 1981 China launched three satellites into space orbit from a single launch vehicle, indicating that China might possess the technology to develop multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). China also launched the Xia-class SSBN in 1981, and the next year it conducted its first successful test launch of the CSS-NX-4 submarine-launched ballistic missile. In addition to the development of a sea-based nuclear force, China began considering the development of tactical nuclear weapons. PLA exercises featured the simulated use of tactical nuclear weapons in offensive and defensive situations beginning in 1982. Reports of Chinese possession of tactical nuclear weapons had remained unconfirmed in 1987.

In 1986 China possessed a credible deterrent force with land, sea and air elements. Land-based forces included ICBMs, IRBMs, and MRBMs. The sea-based strategic force consisted of SSBNs. The Air Force's bombers were capable of delivering nuclear bombs but would be unlikely to penetrate the sophisticated air defenses of modern military powers.

China's nuclear forces, in combination with the PLA's conventional forces, served to deter both nuclear and conventional attacks on the Chinese lands. Chinese leaders pledged to not use nuclear weapons first (no first use), but pledged to absolutely counter-attack with nuclear weapons if nuclear weapons are used against China. China envisioned retaliation against strategic and tactical attacks and would probably strike countervalue rather than counterforce targets. The combination of China's few nuclear weapons and technological factors such as range, accuracy, and response time limited the effectiveness of nuclear strikes against counterforce targets. China has been seeking to increase the credibility of its nuclear retaliatory capability by dispersing and concealing its nuclear forces in difficult terrain, improving their mobility, and hardening its missile silos.

The CJ-10 long-range cruise missile made its first public appearance during the military parade on the 60th Anniversary of the People's Republic of China; the CJ-10 represents the next generation in rocket weapons technology in the PLA.

In late 2009, it was reported that the Corps was constructing a 3,000–5,000-kilometre (1,900–3,100 mi) long underground launch and storage facility for nuclear missiles in the Hebei province.[10] 47 News reported that the facility was likely located in the Taihang Mountains.[11]

On 9 January 2014, a Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) referred to as the WU-14 was allegedly spotted flying at high speeds over the country. The flight was confirmed by the Pentagon as a hypersonic missile delivery vehicle capable of penetrating the U.S. missile defense system and delivering nuclear warheads. The WU-14 is reportedly designed to be launched as the final stage of a Chinese ICBM traveling at Mach 10, or 12,360 km/h (7,680 mph). Two Chinese technical papers from December 2012 and April 2013 show the country has concluded hypersonic weapons pose "a new aerospace threat" and that they are developing satellite directed precision guidance systems. China is the third country to enter the "hypersonic arms race" after Russia and the United States. Russia is jointly developing with India the Mach 6 (7,300 km/h (4,500 mph)) scramjet-powered Brahmos-II. The U.S. Air Force has flown the X-51A Waverider technology demonstrator and the U.S. Army has flight tested the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon.[12] China later confirmed the successful test flight of a "hypersonic missile delivery vehicle," but claimed it was part of a scientific experiment and not aimed at a target.[13]

US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimating that by 2022 the number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100.[14]

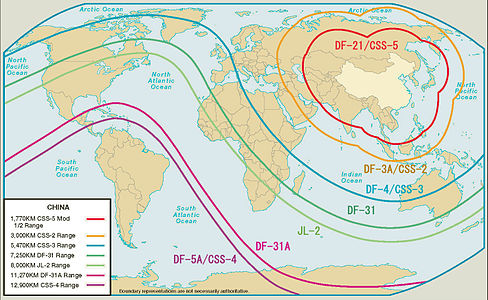

Missile ranges

-

Maximum range for China's conventional SRBM force (2006)

-

Medium and intercontinental ballistic missile ranges (2007)

Active missiles

Intercontinental ballistic missiles

- DF-41 - 10~20 (deployed)

- DF-31B - 20~30

- DF-31A - 30~50

- DF-31 - 8

- DF-5C - 10~15

- DF-5B - 10~20

- DF-5A - 10~20

- DF-4 - 20~35

Intermediate-range ballistic missiles

- DF-26 - 80

Medium-range ballistic missiles

- DF-21D Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile - 50

- DF-21C - 100

- DF-21A - 200

- DF-16 - 50

Short-range ballistic missiles

Cruise missiles

- DF-10A - 500

In Saudi Arabia

The PLARF Gold Wheel Project co-operates the DF-3 and DF-21 missiles in Saudi Arabia since the establishment of Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force in 1984.

See also

- Dongfeng (missile)

- Nuclear triad

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- Qian Xuesen (also known as Tsien Hsue-shen)

References

Citations

- ^ "The PLA Oath" (PDF).

I am a member of the People's Liberation Army. I promise that I will follow the leadership of the Communist Party of China...

- ^ "Federation of American Scientists: Status of World Nuclear Forces". Fas.org. 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ^ 2013 China report, defense.gov

- ^ "China's nuclear policy, strategy consistent: spokesperson - Xinhua | English.news.cn". Xinhua. Beijing: People's Republic of China. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Diplomat, Shannon Tiezzi, The. "The New Military Force in Charge of China's Nuclear Weapons". The Diplomat. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fisher, Richard D., Jr. (6 January 2016). "China establishes new Rocket Force, Strategic Support Force". Jane's Defence Weekly. 53 (9). Surrey, UK: Jane's Information Group. ISSN 0265-3818.

This report also quotes Chinese expert Song Zhongping saying that the Rocket Force could incorporate 'PLA sea-based missile unit[s] and air-based missile unit[s]'.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Keck, Zachary (29 July 2017). "Missile Strikes on U.S. Bases in Asia: Is This China's Real Threat to America?". The National Interest. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Ben R. Rich; Leo Janos (26 February 2013). Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-24693-4.

- ^ Robin D. S. Higham (2003). One Hundred Years of Air Power and Aviation. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-1-58544-241-6.

- ^ "China Builds Underground 'Great Wall' Against Nuke Attack". The Chosun Ilbo. December 14, 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Zhang, Hui (31 January 2012). "China's Underground Great Wall: Subterranean Ballistic Missiles". Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard University. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ China has successfully tested its first hypersonic missile - Army Recognition, 14 January 2014

- ^ Waldron, Greg (16 January 2014). "China confirms test of "hypersonic missile delivery vehicle"". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee (June 2017). Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat (Report). NASIC.

- ^ "Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces". Federation of American Scientists.

Sources

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

Further reading

- Federation of American Scientists et al. (2006): Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

- China Nuclear Forces Guide Federation of American Scientists

- Enrico Fels (February 2008): Will the Eagle strangle the Dragon? An Assessment of the U.S. Challenges towards China's Nuclear Deterrence, Trends East Asia Analysis No. 20.

External links

- Strategic Missile Force SinoDefence.com (WaybackMachine Dec. 2013)

- PLA Second Artillery Corps SinoDefence.com (Dec. 2010)

- Second Artillery Corps FAS.org

- Second Artillery Corps (SAC) NTI.org (WaybackMachine Dec. 2011)