Eucalyptus: Difference between revisions

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

<references /> |

<references /> |

||

*Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med 2002;347:13-18. |

*Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med 2002;347:13-18. |

||

*Jahn, G. C. |

*Jahn, G. C. 1991a. Ant repellent activity of eucalyptus extracts in choice tests. Insecticide & Acaricide Tests 16:293. |

||

*Jahn, G. C. |

*Jahn, G. C. 1991b. Evaluation of the repellent activity of eucalyptus oil to big-headed ants. Insecticide & Acaricide Tests 16:293-294. |

||

*Jahn, G. C. 1992. Effect of Eucalyptus dives extracts on ''Pheidole megacephala'' (F.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. Hawaiian Entomol. Soc. 31:79-81. |

*Jahn, G. C. 1992. Effect of Eucalyptus dives extracts on ''Pheidole megacephala'' (F.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. Hawaiian Entomol. Soc. 31:79-81. |

||

Revision as of 01:31, 12 December 2006

| Eucalyptus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eucalyptus melliodora foliage and flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Eucalyptus |

| Species | |

|

About 700; see the List of Eucalyptus species | |

Eucalyptus is a diverse genus of trees (and a few shrubs), the members of which dominate the tree flora of Australia. There are more than 700 species of Eucalyptus, mostly native to Australia, with a very small number found in adjacent parts of New Guinea and Indonesia and one as far north as the Philippines. Eucalyptus can be found in almost every part of the Australian continent, adapted to all of its climatic conditions; in fact, no other continent is so characterised by a single genus of tree as Australia is by eucalyptus. Many, but far from all, are known as gum trees; other names for various species include mallee, box, ironbark, stringybark, and ash.

Description

Flowers and leaves

The most readily recognisable characteristics of Eucalyptus species are the distinctive flowers and fruits. The name Eucalyptus, from the Greek words eu-, well, and kaluptos, cover, meaning "well-covered", describes the bud cap (botanically called an operculum). This cap forms from modified petals and falls off as the flower opens. Thus flowers have no petals, decorating themselves instead with many showy stamens. The woody fruits, known as gumnuts, are roughly cone-shaped and have valves at the end which open to release the seeds.

Nearly all eucalypts are evergreen but some tropical species lose their leaves at the end of the dry season. As in other members of the Myrtle family, eucalypt leaves are covered with oil glands. The copious oils produced are an important feature of the genus. Eucalypts also commonly exhibit leaf dimorphism. When young, their leaves are opposite, oval to roundish, and occasionally without a petiole. When one to a few years old, the leaves of most species become alternate, lanceolate to falcate (sickle-shaped), quite slender and pendulous with longer petioles. However there are numerous species such as E. melanophloia and E. setosa that retain the juvenile leaf form throughout their life history. The adult leaves of most species, as well as the juvenile leaves of some, are the same on both sides, lacking the distinction between upper and lower surfaces shown by the leaves of most plants. Most species do not flower until adult foliage starts to appear; E. cinerea and E. perriniana are notable exceptions.

Bark

The bark dies annually and species can be roughly grouped based on its appearance. In smooth-barked trees most of the bark is shed, leaving a smooth surface that is often colourfully mottled. With rough-barked trees the dead bark persists on the tree and dries out. Many trees, however, have smooth bark at the top but rough bark on the trunk or its base. The types of rough bark is often used to broadly label a group of eucalypts.

They are:

- Stringybark - consists of long-fibres and can be pulled off in long pieces. It is usually thick with a spongy texture.

- Ironbark - is hard, rough and deeply furrowed. It is soaked with dried kino (a sap exuded by the tree) which gives a dark red or even black colour.

- Tessellated - bark is broken up into many distinct flakes. They are corkish and can flake off.

- Box - has short fibres. Some also show tessellation.

- Ribbon - this has the bark coming off in long thin pieces but still loosely attached in some places. They can be long ribbons, firmer strips or twisted curls.

Related genera

A small genus of similar trees, Angophora, has also been known since the 18th century. In 1995 new evidence, largely genetic, indicated that some prominent eucalypt species were actually more closely related to Angophora than to the other eucalypts; they were split off into the new genus Corymbia. Although separate, the three groups are allied and it remains acceptable to refer to the members of all three genera Angophora, Corymbia and Eucalyptus as "eucalypts". The coolibah trees, referred to in Waltzing Matilda, are eucalypts E. coolabah and E. microtheca.

Tall timber

Today, specimens of the Australian Mountain Ash, Eucalyptus regnans, are among the tallest trees in the world at up to 92 metres in height [1] and the tallest of all flowering plants; taller trees such as the Coast Redwood are all conifers. There is credible evidence however that at the time of European settlement of Australia some Mountain Ash were indeed the tallest plants in the world.

Tolerance

Most eucalypts are not tolerant of frost, or only tolerate light frosts down to -3°C to -5°C; the hardiest, are the so-called Snow Gums such as Eucalyptus pauciflora which is capable of withstanding cold and frost down to about -20°C. Two sub-species, E. pauciflora niphophila and E. pauciflora debeuzevillei in particular are even hardier and can tolerate even quite severe winters.

Several other species, especially from the high plateau and mountains of central Tasmania such as E. coccifera, E. subcrenulata, and E. gunnii have produced extreme cold hardy forms and it is seed procured from these genetically hardy strains that are planted for ornament in colder parts of the world.

Animal relationships

An essential oil extracted from eucalypt leaves contains compounds that are powerful natural disinfectants and which can be toxic in large quantities. Several marsupial herbivores, notably koalas and some possums, are relatively tolerant of it. The close correlation of these oils with other more potent toxins called formylated phloroglucinol compounds allows koalas and other marsupial species to make food choices based on the smell of the leaves. However, it is the formylated phloroglucinol compounds that are the most important factor in choice of leaves by koalas.

Eucalypts support the larvae of a number of Lepidoptera species - see list of Lepidoptera which feed on Eucalyptus.

Hazards

Eucalypts have a habit of dropping entire branches off as they grow. Eucalyptus forests are littered with dead branches. The Australian Ghost Gum Eucalyptus papuana is also termed the "widow maker", due to the high number of pioneer tree-felling workers who were killed by falling branches. Many deaths were actually caused by simply camping under them, as they shed whole and very large branches to conserve water during periods of drought. For this reason, one should never camp under an overhanging branch. This may be the real reason behind the drop bear story told to children - the idea is to keep them away from being under dangerous branches.

Fire

On warm days vapourised eucalyptus oil rises above the bush to create the characteristic distant blue haze of the Australian landscape. Eucalyptus oil is highly flammable (trees have been known to explode) and bush fires can travel easily through the oil-rich air of the tree crowns. The dead bark and fallen branches are also flammable. Eucalypts are well adapted for periodic fires, in fact most species are dependent on them for spread and regeneration, both from reserve buds under the bark, and from fire-germinated seeds sprouting in the ashes.

Eucalypts originated between 35 and 50 million years ago, not long after Australia-New Guinea separated from Gondwana, their rise coinciding with an increase in fossil charcoal deposits (suggesting that fire was a factor even then), but they remained a minor component of the Tertiary rainforest until about 20 million years ago when the gradual drying of the continent and depletion of soil nutrients led to the development of a more open forest type, predominantly Casuarina and Acacia species. With the arrival of the first humans about 50 thousand years ago, fires became much more frequent and the fire-loving eucalypts soon came to account for roughly 70% of Australian forest.

Eucalypts regenerate quickly after fire. After the Canberra bushfires of 2003, hectares of imported species were killed, but in a matter of weeks the gum trees were putting out suckers and looking generally healthy.

The two valuable timber trees, Alpine Ash E. delegatensis and Mountain Ash E. regnans, are killed by fire and only regenerate from seed. The same fire that has had little impact on forests around Canberra has resulted in thousands of hectares of dead ash forests. There has been some debate as to whether to leave the stands, or attempt to harvest the mostly undamaged timber.

Cultivation and uses

Eucalypts have many uses which have made them economically important trees. Perhaps the Karri and the Yellow box varieties are the best known. Due to their fast growth the foremost benefit of these trees is the wood. They provide many desirable characteristics for use as ornament, timber, firewood and pulpwood. Fast growth also makes eucalypts suitable as windbreaks.

Eucalypts draw a tremendous amount of water from the soil through the process of transpiration. They have been planted (or re-planted) in some places to lower the water table and reduce soil salination. Eucalypts have also been used as a way of reducing malaria by draining the soil in Algeria, Sicily[2] and also in Europe and California[3]. Drainage removes swamps which provide a habitat for mosquito larvae, but such drainage can also destroy ecologically productive areas.

Eucalyptus oil is readily steam distilled from the leaves and can be used for cleaning, deodorising, and in very small quantities in food supplements; especially sweets, cough drops and decongestants. Eucalyptus oil has insect repellent properties (Jahn 1991 a, b; 1992), and is an active ingredient in some commercial mosquito repellents (Fradin and Day 2002).

The nectar of some eucalyptus produces high quality monofloral honey. In the western United States the flowering is in late January, before the flowering of commercial nut and fruit trees, thus it is easily segragated and the honey produced has a flavour described as "buttery [citation needed].

The ghost gum's leaves were used by Aborigines to catch fish. Soaking the leaves in water releases a mild tranquiliser which stuns fish temporarily.

Eucalyptus is also used to make the digeridoo, a musical wind instrument made popular by the Aborigines of Australia.

Plantation and ecological problems

Eucalyptus were first introduced to the rest of the world by Sir Joseph Banks, botanist on the Cook expedition in 1770. They have subsequently been introduced to many parts of the world, notably California, Brazil, Morocco, Portugal, South Africa, Israel and Galicia. Several species have become invasive and are causing major problems for local ecosystems. In Spain, they have been planted in pulpwood plantations, replacing native oak woodland. As in other such areas, while the original woodland supports numerous species of native animal life (insects, birds, salamanders, etc.), the eucalypt groves are inhospitable to the local wildlife which is not adapted to them, leading to silent forests and the decline of wildlife populations. On the other hand, eucalyptus are the basis for several industries, such as sawmilling, pulp, charcoal and others.

California

In the 1850s many Australians traveled to California to take part in the California Gold Rush. Much of California has similar climate to parts of Australia and some people got the idea of introducing eucalyptus. By the early 1900s thousands of acres of eucalyptus were planted with the encouragement of the state government. It was hoped that they would provide a renewable source of timber for construction and furniture making. However this did not happen partly because the trees were cut when they were too young and partly because the Americans did not know how to process the cut trees to prevent the wood from twisting and splitting.[1]

One way in which the eucalyptus, mainly the blue gum E. globulus, proved valuable in California was in providing windbreaks for highways, orange groves, and other farms in the mostly treeless central part of the state. They are also admired as shade and ornamental trees in many cities and gardens.

Eucalyptus forests in California have been criticized because they drive out the native plants and do not support native animals. Fire is also a problem. The 1991 Oakland Hills firestorm which destroyed almost 3,000 homes and killed 25 people was partly fueled by large numbers of eucalyptus in the area close to the houses.[2]

In some parts of California eucalyptus forests are being removed and native trees and plants restored. Individuals have also illegally destroyed some trees and are suspected of introducing insect pests from Australia which attack the trees.[3]

References

- ^ J.E. Hickey, P. Kostoglou, G.J. Sargison. "Tasmania's Tallest Trees" (PDF). Forestry Tasmania. Retrieved 2005-01-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|media=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mrs. M. Grieve. "A Modern Herbal:Eucalyptus". Retrieved 2005-01-27.

- ^ Santos, Robert L. "The Eucalyptus of California". Alley-Cass Publications. Retrieved 2005-01-27.

- Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med 2002;347:13-18.

- Jahn, G. C. 1991a. Ant repellent activity of eucalyptus extracts in choice tests. Insecticide & Acaricide Tests 16:293.

- Jahn, G. C. 1991b. Evaluation of the repellent activity of eucalyptus oil to big-headed ants. Insecticide & Acaricide Tests 16:293-294.

- Jahn, G. C. 1992. Effect of Eucalyptus dives extracts on Pheidole megacephala (F.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. Hawaiian Entomol. Soc. 31:79-81.

External links

- EUCLID Sample, CSIRO

- The Eucalyptus Page

- EucaLink

- Currency Creek Arboretum - Eucalypt Research

- [4] Duke, James A. Handbook of Energy Crops. 1983.

- [5] Henter, Heather. "Tree Wars: The Secret Life of Eucalyptus"

- [6] Santos, Robert. "The Eucalyptus of Califonia: Seeds of Good or Seeds of Evil?" 1997 Denair, CA : Alley-Cass Publications

- [7] Williams, Ted. "America's Largest Weed" Audubon Magazine, January 2002

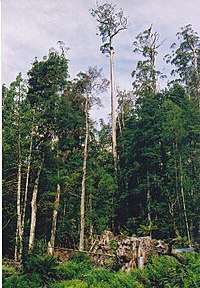

Photo gallery

-

Eucalyptus forest in East Gippsland, Victoria. Mostly Eucalyptus albens (white box).

-

Eucalyptus forest in East Gippsland, Victoria. Mostly Eucalyptus albens (white box).

-

Eucalyptus forest in East Gippsland, Victoria. Mostly Eucalyptus albens (white box).

-

A eucalyptus tree with the sun shining through its branches.

-

Eucalyptus bridgesiana (Apple box) on Red Hill, Australian Capital Territory.

-

Eucalyptus cinerea x pulverulenta - National Botanical Gardens Canberra

-

Eucalyptus leuxoxylon 'Rosea'

-

Eucalyptus gall

-

Eucalyptus grandis. Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina.