Napoleon III's Louvre expansion

The expansion of the Louvre under Napoleon III in the 1850s, known at the time as the Nouveau Louvre[1][2] or Louvre de Napoléon III,[3] was an iconic project of the Second French Empire and a centerpiece of its ambitious transformation of Paris.[4] Its design was initially produced by Louis Visconti and, after Visconti's death in late 1853, modified and executed by Hector Lefuel. It represented the completion of a centuries-long project, sometimes referred to as the grand dessein ("grand design"), to connect the old Louvre Palace around the Cour Carrée with the Tuileries Palace to the west. Following the Tuileries' arson at the end of the Paris Commune in 1871 and demolition a decade later, Napoleon III's nouveau Louvre became the eastern end of Paris's axe historique centered on the Champs-Élysées.

The project was initially intended for mixed ceremonial, museum, housing and administrative use, including the offices of the ministère d’Etat which after 1871 were attributed to the Finance Ministry. Since 1993, all its spaces have been used by the Louvre Museum.

Project development

Following the French Revolution of 1848, the provisional government adopted a decree on the continuation of the rue de Rivoli toward the east and the completion of the Louvre Palace's north wing, building on the steps taken to that effect under Napoleon. Architects Louis Visconti and Émile Trélat produced a draft design for completing the entire palace and presented it to the Legislative Assembly in 1849.[2]: 155 These plans were not implemented, however, until Napoleon III developed them into a more ambitious plan after becoming Emperor following his successful coup d'état on 2 December 1851.[4]

Visconti was made architect to the Tuileries on 7 July 1852. His architectural concept for the New Louvre was swiftly approved by the emperor, and the first stone was laid on 25 July 1852.[2]: 155

After Visconti died of a heart attack on 29 December 1853, Hector Lefuel, by then the architect of the Palace of Fontainebleau, was appointed to replace him. Lefuel modified Visconti's project, keeping its broad architectural outlines but opting for a considerably more exuberant decoration program that came to define the nouveau Louvre in the eyes of many observers. Old houses and other buildings that still encroached on the central space of the Louvre-Tuileries complex, between the Cour Carrée and the place du Carrousel, were swept clear. The project was swiftly executed, and was substantially completed at the time of its inauguration by the emperor on 14 August 1857.[3]

Aiding Lefuel was the young American architect Richard Morris Hunt, who had studied under Lefuel at the École des Beaux-Arts. Following Hunt's graduation, Lefuel made Hunt inspector of the Louvre work and allowed him to design the façade of the pavillon de la Bibliothèque facing the rue de Rivoli.[5]

-

One of many earlier unrealized proposals for the completion of the Louvre, by Percier and Fontaine (1807 or 1808)

-

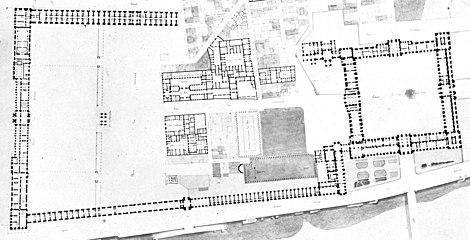

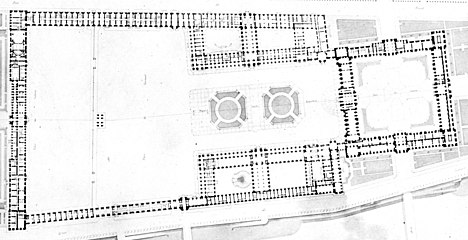

Plan of the unfinished Louvre by Charles Vasserot (1830)

-

Design of the Louvre expansion by Louis Visconti (1853)

-

Visconti presents the plans for the Nouveau Louvre to Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie in 1853 at the Tuileries, painting by Jean-Baptiste-Ange Tissier (1865). Lefuel is the bearded figure in the shadow on the far right-hand side.

-

Engraving dedicated "to His Majesty the Emperor" showcasing Visconti's design, by Rudolf Pfnor (1853)

-

Celebratory tapestry cartoon[3] showing the expanded Louvre between a cherub holding an ribbon inscribed with "LE LOUVRE DE NAPOLEON III" (lower left) and two angels holding the emperor's profile (upper right), by Victor Chavet (1857)

Description

The Nouveau Louvre mostly consists of two sets of buildings or wings, on the north and south sides of a central space now called Cour Napoléon. The new buildings were structured around a sequence of pavilions that were given names of French statesmen from Ancien Régime (North Wing) and Napoleonic times (South Wing), still used to this day: from the northwest to the southwest, pavillon Turgot, pavillion Richelieu, pavillon Colbert, pavillon Sully (the project's new name for the pre-existing pavillon de l'Horloge), pavillon Daru topping the eponymous staircase, pavillon Denon, and pavillon Mollien also featuring a monumental staircase.[2]: 155 (From 1989, the names of the three central pavilions have also been given to the entire respective wings of the Louvre complex. Thus, the Louvre's North Wing is now known as aile Richelieu; its eastern square of buildings around the Cour Carrée is the aile Sully; and the Nouveau Louvre's South Wing is the aile Denon.)

Lefuel created two octagonal gardens at the center of the Cour Napoléon (now replaced by the Louvre Pyramid). Napoleon III intended to adorn these with equestrian statues of, respectively, Louis XIV and Napoleon I, expressing his claim to legitimacy as the inheritor of France's two (royal and imperial) strands of monarchical development - a narrative that was simultaneously developed in the emperor's new Musée des Souverains, also in the Louvre. This program, however, was not realized.[2]: 155 In various other parts of the project, Napoleon III emphasized his role as continuator of the great French monarchs of the past, and as the one who completed their unfinished work. On both sides of the Pavillon Sully, black marble plaques bear gilded inscriptions that read, respectively: "1541. François Ier commence le Louvre. 1564. Catherine de Médicis commence les Tuileries" and "1852-1857. Napoléon III réunit les Tuileries au Louvre."[2]: 156

On the eastern side of the Cour Napoléon, the project entailed no new building but rather the exterior refacing of the pre-existing palace whose interior rooms were left unchanged. For the central pavillon de l'Horloge's new western façade, Visconti took inspiration from both its eastern side designed by Jacques Lemercier in the 1620s and from the central pavilion of the Tuileries Palace. The same inspiration shaped the pavilions named after Richelieu and Denon on the Cour Napoléon's northern and southern sides. Lefuel transformed Visconti's understated original design and added a profusion of elaborate sculptural detail. Despite being criticized by Ludovic Vitet in 1866,[citation needed] Lefuel's treatment of the square-dome-roofed pavilions became a seminal model for Second Empire architecture in France and elsewhere.

Inside the North Wing were prestige apartments for some of the regime's principal figures, including those of Charles de Morny, now known as the appartements Napoléon III, served by a monumental staircase later known as the escalier du ministre; administrative offices for the ministère d'Etat, the ministère de la Maison de l'Empereur (separated from the ministère d'Etat in 1860),[6] and the ministère des Beaux-Arts (created in 1870);[7] barracks; and the Bibliothèque du Louvre, personal property of the emperor but open to the public, on the upper floor between the pavillon Richelieu and the rue de Rivoli.[2]: 176 The latter was acceded by another monumental staircase, known as escalier Lefuel since the late 19th century.

The South Wing was largely devoted to new spaces for the Louvre Museum. These included, on the upper ground floor, a new entrance lobby flanked by two long stone-clad galleries, respectively named after Napoleon's ministers Pierre, comte Daru (galerie Daru) and Nicolas François, Count Mollien (galerie Mollien), with the monumental staircases bearing those same names at both ends; and on the first floor, high-ceilinged exhibition rooms for large paintings, the salle Daru and salle Mollien, with the pavillon Denon in the middle. On the South Wing's first floor, between the pavillon Denon and the Grande Galerie, Lefuel created a large Estates Hall (salle des États) for state events and ceremonies.

Below these prestige spaces was an extensive complex of stables for up to 149 horses and 34 carriages.[8] At the center of it is the brick-and-stone salle du Manège, a monumental indoor space for horse-riding under the salle des Etats, between the South Wing's two interior courts named after Caulaincourt (west) and Visconti (east). (The cour Caulaincourt was renamed after Lefuel following the architect's death in 1880.) The stables were supervised by a "great equerry" (grand écuyer) whose apartment was on the western side of the Cour Lefuel, adorned with a porticoed balcony. The South wing also included barracks for the Cent-gardes Squadron and lodgings for the palace's service personnel.[2]: 158

-

North Wing

-

Escalier du Ministre

-

Escalier Lefuel

-

Escalier Colbert

-

Appartements Napoléon III

-

Appartements Napoléon III

-

Galerie Daru

-

Salle Daru

-

Pavillon Denon ceiling

-

Escalier Mollien

-

Cour Lefuel with ramps to the salle du Manège

-

Interior of the salle du Manège

-

Pavillon de la Bibliothèque on the rue de Rivoli

Statuary

Sculptural profusion was one of the defining features of Lefuel's approach. Arguably the most salient component is the series of 86 statues of celebrated figures (hommes illustres) from French history and culture, each one labelled with their name. These include, following the order of the wings from northwest to southwest:

- North Wing, western side: La Fontaine, by Jean-Louis Jaley; Pascal, by François Lanno; Mézeray, by Louis-Joseph Daumas; Molière, by Bernard Seurre; Boileau, by Charles Émile Seurre; Fénelon, by Jean-Marie Bonnassieux; La Rochefoucauld, by Noël-Jules Girard; and Corneille, by Henri Lemaire.

- North Wing, southern side: Gregory of Tours, by Jean Marcellin; François Rabelais, by Élias Robert (now a copy); Malherbe, by Jean-Jules Allasseur; Abelard, by Jules Cavelier; Colbert, by Raymond Gayrard (copy); Mazarin, by Pierre Hébert; Buffon, by Eugène André Oudiné; Froissart, by Henri Lemaire; Rousseau, by Jean-Baptiste Farochon; Montesquieu, by Charles-François Lebœuf; Mathieu Molé, by Charles-François Lebœuf; Turgot, by Pierre Travaux; Saint Bernard, by François Jouffroy; La Bruyère, by Joseph-Stanislas Lescorné; Suger, by Nicolas Raggi; Jacques Auguste de Thou, by Auguste-Louis Deligand; Bourdaloue, by Louis Desprez; Racine, by Michel-Pascal; Voltaire, by Antoine Desboeufs; Bossuet, by Louis Desprez; Condorcet, by Pierre Loison (sculpteur); Denis Papin, by Jean-François Soitoux; Sully, by Vital-Dubray (copy); Vauban, by Gustave Crauck; Lavoisier, by Jacques-Léonard Maillet; and Jérôme Lalande, by Jean-Joseph Perraud.

- Eastern side of the Cour Napoléon: Louvois, by Aimé Millet; Saint-Simon, by Pierre Hébert; Joinville, by Jean Marcellin; Esprit Fléchier, by François Lanno; Commynes, by Eugène-Louis Lequesne; Jacques Amyot, by Pierre Travaux; Mignard, by Debay fils; Massillon, by François Jouffroy; Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau, by Georges Diebolt; Jean Goujon, by Bernard Seurre; Claude Lorrain, by Auguste-Hyacinthe Debay; Grétry, by Victor Vilain; Jean-François Regnard, by Théodore-Charles Gruyère; Jacques Cœur, by Élias Robert; Enguerrand de Marigny, by Nicolas Raggi; Chénier, by Auguste Préault; Jean-Balthazar Keller, by Pierre Robinet; and Antoine Coysevox, by Jules-Antoine Droz.

- South Wing, northern side: Jean Cousin the Younger, by Napoléon Jacques; Le Nôtre, by Jean-Auguste Barre; Clodion, by Vital-Dubray; Germain Pilon, by Louis Desprez; Ange-Jacques Gabriel, by Augustin Courtet; Le Pautre, by Bosio the Younger; Michel de l'Hôpital, by Eugène Guillaume; Lemercier, by Antoine Laurent Dantan; Descartes, by Gabriel Garraud; Ambroise Paré, by Michel-Pascal; Richelieu, by Jean-Auguste Barre; Montaigne, by Jean-François Soitoux; Houdon, by François Rude (copy); Étienne Dupérac, by Jacques Ange Cordier; Jean de Brosse, by Auguste Ottin; Cassini de Thury, by Hippolyte Maindron; d'Aguesseau, by Louis-Denis Caillouette; Hardouin-Mansart, by Jean-Joseph Perraud; Poussin, by François Rude (copy); Gérard Audran, by Jacques-Léonard Maillet; Jacques Sarazin, by Honoré-Jean-Aristide Husson; Nicolas Coustou, by Augustin Courtet; Le Sueur, by Honoré-Jean-Aristide Husson; Claude Perrault, by Auguste-Hyacinthe Debay; Philippe de Champaigne, by Louis-Adolphe Eude; and Puget, by Antoine Étex.

- South Wing, western side: Lescot, by Henri de Triqueti; Bullant, by Pierre Robinet; Le Brun, by Jean-Claude Petit; Pierre Chambiges, by Jules-Antoine Droz; Libéral Bruand, by Armand Toussaint; Philibert de l'Orme, by Jean-Pierre Dantan; Palissy, by Victor Huguenin; and Rigaud, by Victor Thérasse.

Among the abundant architectural sculpture of the Nouveau Louvre, the pediments of the three main pavilions stand out:[2]: 156 [9]

- Pavillon Richelieu: "France distributing crowns to its worthiest children", by Francisque Joseph Duret;

- Pavillon Sully: "Napoleon I above History and Arts", by Antoine-Louis Barye and Pierre-Charles Simart;

- Pavillon Denon: "Napoleon III surrounded by Agriculture, Industry, Commerce and the Fine Arts", by Simart.

The latter group includes the depiction of a steam locomotive, then representing cutting-edge technological progress, and the only surviving public portrayal of Napoleon III in Paris.[10]

-

Pediment, Pavillon Richelieu

-

Pediment, Pavillon Sully

-

Pediment, Pavillon Denon

The salle du Manège in the South Wing was another opportunity for Lefuel to foster a rich structural program, which was only executed in 1861 after the Nouveau Louvre's inauguration. Outside in the Cour Lefuel, four bronze groups of wild animals by Pierre Louis Rouillard stand at the start of the two horse ramps : Chienne et ses petits, Loup et petit chien, Chien combattant un loup, and Chien combattant un sanglier. At the top of the ramps above the entrance to the manège, a monumental group, also by Rouillard, features three surging horses that echo Robert Le Lorrain's chevaux du soleil at the Hôtel de Rohan (Paris). Inside, the idiosyncratic hunting-themed capitals feature heads of horses and other animals, by Emmanuel Frémiet, Rouillard, Alfred Jacquemart, Germain Demay, and Houguenade.[11]

-

Rouillard's wild animals in the Cour Lefuel

-

Rouillard's "dog fighting a wolf"

-

Rouillard's "wolf and puppy"

-

Rouillard's three horses above the Manège's entrance

-

One of the capitals of the Salle du Manège

Later history

In 1861, the Pavillon de Flore was in serious disrepair. Following the successful completion of the Louvre expansion, Napoleon III commissioned Lefuel to rebuild it and the wing that connected it to the Nouveau Louvre's South Wing, on the first floor of which was the Grande Galerie. Part of the project involved the creation of a new salle des Etats closer to the Tuileries, in a protruding wing known as the pavillon des Sessions, in the place of the western third of the Grande Galerie which was correspondingly cut short. The Southern façade was completely changed, as Lefuel replaced Louis Le Vau's colossal order with a replica of the earlier design further to the east. At the eastern end of the new project, Lefuel created monumental archways for the road connecting the Pont du Carrousel to the south with the rue de Rohan to the north, known as the guichets du Louvre or guichets du Carrousel. The project was completed in 1869 as an equestrian statue of Napoleon III by Antoine-Louis Barye was placed above the arches of the guichets. Further west are pairs of monumental lions by Antoine-Louis Barye and lionesses by Auguste Cain, respectively on the South and North side of the porte des Lions, with two additional lionesses by Cain in front of the nearby porte Jaujard.

That setting, however, did not last long, as the Second Empire came to its abrupt end. On 6 September 1870, days after the emperor’s capture at the Battle of Sedan, Barye's equestrian statue was topped and destroyed.[12] At the end of the Paris Commune on 23 May 1871, the Tuileries Palace was burned down, as also was the Bibliothèque du Louvre. Lefuel, together with Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, defended the option of repairing the ruins, but shortly after both dies the French parliament decided to tear them down in 1882, largely for political reasons associated with the termination of the monarchy. After the remains of the Tuileries were razed in 1883, the layout that had been created by Napoleon III and Lefuel was fundamentally altered.

In the context of the Grand Louvre project initiated by President François Mitterrand in the 1980s, the French Finance Ministry was compelled to leave the Louvre's North Wing. While most of the interior spaces were gutted and rebuilt, the more artistically and historically significant ones were preserved and renovated. These included three monumental staircases, the escalier Lefuel, escalier du ministre and escalier Colbert; the former ministerial office, rebranded as Café Richelieu; and the palatial suite of rooms created by Lefuel and his team for the Duke of Morny, rebranded as appartements Napoléon III. The Café Marly, located outside of the Louvre museum in the same wing and opened in 1994, has been designed by Olivier Gagnère in a reinterpretation of the Second Empire style.[13] Meanwhile, the Cour Napoléon was radically transformed with the erection of the Louvre Pyramid and of the copy in lead of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's equestrian statue of Louis XIV.

Influence

The nouveau Louvre was highly influential and became the exemplar of the Napoleon III style, also known as Second Empire architecture, subsequently adopted in numerous buildings in France as well as elsewhere in Europe and in the world. Prominent examples in the United States include the Old City Hall in Boston (built 1862-1865), the State, War, and Navy Building in Washington DC (built 1871-1888), and the Philadelphia City Hall (built 1871-1901).

See also

Notes

- ^ Théodore de Banville (1857). Paris et le Nouveau Louvre. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Galignani's New Paris Guide, for 1870: Revised and Verified by Personal Inspection, and Arranged on an Entirely New Plan. Paris: A. and W. Galignani and C°. 1870.

- ^ a b c Karine Huguenaud. "Le Louvre de Napoléon III". Fondation Napoléon.

- ^ a b David H. Pinkney (June 1955). "Napoleon III's Transformation of Paris: The Origins and Development of the Idea". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ William Roscoe Thayer, ed. (1893), "Richard Morris Hunt", The Harvard Graduates' Magazine, I, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association

- ^ Xavier Mauduit (2008). "Le ministère du faste : la Maison de l'Empereur Napoléon III". Parlement[s], Revue d'histoire politique.

- ^ "Les prémices du Ministère : Tentatives éphémères d'une administration des Beaux Arts autonome à partir du Second Empire". Ministère de la Culture.

- ^ Frédéric Lewino; Anne-Sophie Jahn (16 May 2015). "Visite interdite du Louvre #4 : la magnifique rampe en fer à cheval de la cour des Écuries". Le Point.

- ^ Georges Poisson (1994), "Quand Napoléon III bâtissait le Grand Louvre", Revue du Souvenir Napoléonien: 22-27

- ^ "Le Louvre et Napoléon III". Paris Autrement. 14 January 2014.

- ^ Geneviève Bresc-Bautier (1995), The Louvre: An Architectural History, New York: The Vendome Press, p. 144, 154

- ^ Michèle Beaulieu (1946). "Les esquisses de la décoration du Louvre au Département des sculptures". Bulletin Monumental.

- ^ Dominique Poiret (28 November 2012). "Les terres cuites d'Olivier Gagnère valorisent Vallauris". Libération.

![Celebratory tapestry cartoon[3] showing the expanded Louvre between a cherub holding an ribbon inscribed with "LE LOUVRE DE NAPOLEON III" (lower left) and two angels holding the emperor's profile (upper right), by Victor Chavet [fr] (1857)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/Lens_-_Inauguration_du_Louvre-Lens_le_4_d%C3%A9cembre_2012%2C_la_Galerie_du_Temps%2C_n%C2%B0_205.JPG/600px-Lens_-_Inauguration_du_Louvre-Lens_le_4_d%C3%A9cembre_2012%2C_la_Galerie_du_Temps%2C_n%C2%B0_205.JPG)