History of the Georgia Institute of Technology

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology began shortly after the American Civil War and extends nearly 150 years. In that time, the Institute has undergone significant change, expanding from a small trade school to the largest technological institution in the Southeastern United States. A number of influential leaders and events create obvious divisions in the timeline of Georgia Tech's history. These divisions include the Institute's establishment, its early years, the transformation from trade school to research institute, and its modern history. The National Register of Historic Places has listed the Georgia Tech Historic District since 1978.

Establishment

The idea of Georgia Institute of Technology was introduced in 1865 during the Reconstruction period. Two former Confederate officers, Major John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who had become prominent citizens in the town of Macon, Georgia after the war, strongly believed that the South needed to improve its technology to compete with the industrial revolution that was occurring throughout the North. Many Southerners at this time agreed with this idea. However, because the American South of that era was mainly comprised of agricultural workers and few technical developments were occurring, a technology school was needed.[1]

In 1882, prominent Georgians, authorized by the Georgia state legislature and led by Harris, formed a committee and visited the Northeast to see firsthand how technology schools worked. Using examples from the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science (now Worcester Polytechnic Institute) and Boston Tech (now Massachusetts Institute of Technology), the Atlanta technology school began development on the Worcester Free Institute model, which stressed a combination of "theory and practice." The latter component included student employment and production of consumer items to generate revenue for the school.[2]

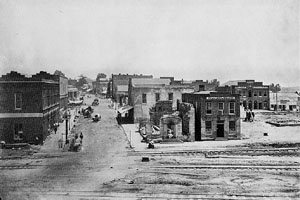

Patrick Hues Mell, the president of the University of Georgia at that time, was a firm believer that it should be located at Athens with the University's main campus, like the Agricultural and Mechanical School. Despite Mell's arguments, the new school was an independent institution.[3] The school was located near the northern city limits of Atlanta at the time of its founding (the city has now expanded several miles beyond it). A historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus notes that the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held fortifications built to protect Atlanta during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. The surrender of the city took place on the southwestern boundary of the modern Georgia Tech campus in 1864.[4]

Early Years

- Includes the administrations of Lyman Hall (1896–1905), Isaac S. Hopkins (1888–1896), and Kenneth G. Matheson (1906–1922)

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1885 with only two buildings. One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a workshop with a foundry, forge, boiler room and engine room. It was designed specifically for students to work and produce goods to sell, creating revenue for the school while learning vocational skills. The two buildings were equal in size to show the importance of teaching both the mind and the hands;[1] at the time, however, there was some disagreement as to whether the machine shop should have been used to turn a profit.[2] The only degree offered was a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering.[5] The initial enrollment consisted of 95 men, with all but two from Georgia.[5]

In 1887, Atlanta pioneer Richard Peters sold five acres of his extensive land holdings to the state for $10,000 and donated another four to expand the campus.[6] In February 1899, Georgia Tech opened the first textile engineering school in the south.[7] It was housed in the A. French building, named after the chief donor, Aaron French. The textile engineering program would remain in the A. French building until the Harrison Hightower Textile Engineering Building was completed in 1949.[7][8]

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Georgia Tech campus. On the steps of Tech Tower, Roosevelt presented a speech about the importance of technological education.[9] He then shook hands with every student.[10]

The Technique, the weekly student newspaper, began publication on November 17, 1911.[11]

The Evening School of Commerce began holding classes in 1912.[11]

From Trade School to Technological University

- Includes the administration of Marion L. Brittain (1922–1944)

During its first fifty years, Tech grew from a narrowly focused trade school to a regionally recognized technological university. It was also the home of early radio station WGST AM (Georgia School of Technology) from 1924 to 1930.[12]

In 1931, the Board of Regents transferred control of the Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia and moved the civil and electrical engineering courses at UGA to Tech.[13] Tech replaces the commerce school with what will later become the College of Management. The commerce school will later split from UGA and eventually become Georgia State University.[11] See also: History of Georgia State University

The State Engineering Experiment Station (EES) was chartered by the Georgia Legislature in 1919,[11] but didn't begin operation until 1934 with three researchers and a $12,000 annual budget. The station was created to develop the resources, industries, and commerce of Georgia by providing high-quality research while assisting with national science, technology, and preparedness programs.[14] EES's initial areas of focus were textiles, ceramics, and helicopter engineering. Much early research was conducted in the Hinman Building, which now houses GTRI's Machine Services Department.[14]

Until the mid 1940s, the school required students to be able to create a simple electric motor regardless of their major.[15] During the second world war, as an engineering school with strong military ties through its ROTC program, Georgia Tech was swiftly enlisted for the war effort. In early 1942 the traditional nine-month semester system was replaced by a year-round trimester year, enabling students to complete their degrees a year earlier. Under the plan, students were allowed to complete their engineering degrees while on active duty.[16] During World War II, Georgia Tech was one of only five U.S. colleges feeding the U.S. Navy's officer program.

From Technological University to Research Institute

- Includes the administrations of Blake R. Van Leer (1944–1956), Edwin D. Harrison (1957–1969), and Arthur G. Hansen (1969–1971), and Joseph M. Pettit (1972–1986)

Founded as the Georgia School of Technology, it assumed its present name in 1948 to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research.[17] Unlike similarly-named universities (such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology), the Georgia Institute of Technology is a public institution.

The Southern Technical Institute (STI) was established in 1948 in barracks on the campus of the Naval Air Station Atlanta (now DeKalb Peachtree Airport) in Chamblee, northeast of Atlanta.[18] At that time, all colleges in Georgia were considered extensions of the state's four research universities, and the Southern Technical Institute belonged to Georgia Tech. STI was begun as an engineering technology school, to help military personnel returning from World War II gain a hands-on experience in technical fields. Around 1958, the school moved to Marietta, to land donated by Dobbins Air Force Base.

The school's first female students were admitted in 1952,[19] although it wasn't until 1968 that women could enroll in all programs at Tech (with Industrial Engineering being the last program to open to women).[19][20] The first women's dorm, Fulmer Hall, opened in 1969.[20] Women constituted 28.6% of the undergraduates and 25.8% of the graduate students enrolled in Fall 2006.[21]

In 1961, Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to desegregate without a court order.[22] However, Lester Maddox chose to close his restaurant (located near the modern-day Burger Bowl) rather than desegregate after losing a year-long legal battle in which he challenged the constitutionality of the public accommodations section of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[23]

In 1981, the Southern Technical Institute was split from Georgia Tech, around the same time most of the other regional schools were separated from University of Georgia, Georgia State University, and Georgia Southern University.

Modern history

- Includes the administrations of John Patrick Crecine (1987–1994) and G. Wayne Clough (1994–present)

In 1988, John Patrick Crecine proposed a controversial restructuring of the university. The Institute at that point had three colleges: the College of Engineering, the College of Management, and the catch-all COSALS, the College of Sciences and Liberal arts. Crecine reorganized the latter two into the College of Computing, the College of Sciences, and the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs.[24] Crecine announced the changes without asking for input, and consequently many faculty members disliked him for his top-down management style.[24] In 1989, the administration sent out ballots, and the proposed changes passed, with very slim margins.[24] The restructuring took effect in January 1990. While Crecine was seen in a poor light at the time, the changes he made are considered visionary.[24]

There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire.

In October 1990,[25] Tech's first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL), opened.[26] It is a non-profit corporation operating under French law. GTL is primarily focused on graduate education, sponsored research, and an undergraduate summer program. In 1997, GTL was sued under Toubon Law because all course descriptions on its internet site were in English; these course descriptions constituted an advertisement for this private college and thus fell under the Toubon law.[27] The case was dismissed on a technicality.[28] See also: Toubon Law and The Georgia Tech Lorraine case.

The 1992 Vice-Presidential Candidates Debate between Al Gore, Dan Quayle, and Admiral James Stockdale, held on October 13 1992, took place on the Georgia Tech campus at the Ferst Center for the Arts.[29]

John Patrick Crecine was instrumental in securing the 1996 Summer Olympics for Atlanta. A dramatic amount of construction occurred, creating most of what is now considered "West Campus" in order for Tech to serve as the Olympic Village. The new Undergraduate Living Center, Woodruff Residence Halls and Dining Hall, Eighth Street Apartments, Hemphill Apartments, and Center Street Apartments housed athletes and journalists. The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center was built for swimming events, and the Alexander Memorial Coliseum was renovated.[26]

In 1994, G. Wayne Clough became the first Tech alumnus to serve as the President of the Institute, and was in office during the 1996 Summer Olympics. In 1998, he separated the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs into the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and returned the College of Management to "College" status. His tenure has been focused on a dramatic expansion of the institute, a revamped Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), and the creation of an International Plan.[30][31]

See also

References

- ^ a b "The Hopkins Administration, 1888-1895". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion": The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b Brittain, James E. (1977). "Engineers and the New South Creed: The Formation and Early Development of Georgia Tech". Technology and Culture. 18 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 175–201. doi:10.2307/3103955.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mell, P.H., Jr. (1895). "CHAPTER XIX. Efforts Towards Completing the Technological School as a Department of the University of Georgia". Life of Patrick Hues Mell. Baptist Book Concern. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lenz, Richard J. (2002). "Surrender Marker, Fort Hood, Change of Command Marker". The Civil War in Georgia, An Illustrated Travelers Guide. Sherpa Guides. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "GT Buildings: GTVA-UKL999-A". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "A Walk Through Tech's History". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b "Splendid Growth" - The Textile Educational Enterprise at Georgia Tech

- ^ French Building has unique history, old world flavor

- ^ Selman, Sean (2002-03-27). "Presidential Tour of Campus Not the First for the Institute". A Presidential Visit to Georgia Tech. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "One Hundred Years Ago Was Eventful Year at Tech". BuzzWords. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. 2005-10-01. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d "Tech Timeline: 1910s". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "Tech Timeline: 1920s". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "Tech Timeline: 1930s". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b "GTRI History". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Guertin, Karl (2004-02-13). "Tech's moniker reveals its true history". The Technique. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ World War II and the Tech Connection

- ^ Georgia Tech History & Traditions

- ^ Southern Polytechnic State University. "Southern Polytechnic: History".

- ^ a b Terraso, David (2003-03-21). "Georgia Tech Celebrates 50 Years of Women". Georgia Institute of Technology News Room. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Tech Timeline: 1960s". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Office of Institutional Research & Planning: Facts and Figures: Enrollment by Gender

- ^ "Georgia Tech is Nation's No. 1 Producer of African-American Engineers in the Nation" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2001-09-13. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nystrom, Justin (2004-04-20). "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Lester Maddox". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b c d Joshi, Nikhil (2006-03-10). "Geibelhaus lectures on controversial president". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire.

- ^ "About Georgia Tech Lorraine". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b "Tech Timeline: 1990s". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Wiggins, Mindy (1997-01-17). "GT Lorraine sued over Web site". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "GlobalVision :: Toubon Law". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "The Gore-Quayle-Stockdale Vice Presidential Debate". Commission on Presidential Debates.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Joshi, Nikhil (2005-03-04). "International plan takes root". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Chen, Inn Inn (2005-09-23). "Research, International Plan Fair hits Skiles Walkway". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.