Perseverance (rover)

| Perseverance | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mars 2020 | |

Self-portrait by Perseverance in September 2021 at Rochette, a rock and the site of the first core samples of the Mars 2020 mission. | |

| Typ | Mars rover |

| Owner | NASA |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Specifications | |

| Dimensions | 2.9 m × 2.7 m × 2.2 m (9 ft 6 in × 8 ft 10 in × 7 ft 3 in) |

| Dry mass | 1,025 kilograms (2,260 lb) |

| Communication | |

| Power | MMRTG; 110 W (0.15 hp) |

| Rocket | Atlas V 541 |

| Instruments | |

| History | |

| Launched |

|

| Deployed |

|

| Standort | Jezero crater, Mars |

| Travelled | 2.83 km (1.76 mi) on Mars as of 9 December 2021[update][1] |

Perseverance, nicknamed Percy,[2] is a car-sized Mars rover designed to explore the crater Jezero on Mars as part of NASA's Mars 2020 mission. It was manufactured by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and launched on 30 July 2020, at 11:50 UTC.[3] Confirmation that the rover successfully landed on Mars was received on 18 February 2021, at 20:55 UTC.[4][5] As of 3 September 2024, Perseverance has been active on Mars for 1258 sols (1293 Earth days) since its landing. Following the rover's arrival, NASA named the landing site Octavia E. Butler Landing.[6][7]

Perseverance has a similar design to its predecessor rover, Curiosity, from which it was moderately upgraded. It carries seven primary payload instruments, nineteen cameras, and two microphones.[8] The rover also carried the mini-helicopter Ingenuity to Mars, an experimental aircraft and technology showcase that made the first powered flight on another planet on 19 April 2021.[9] Since its first flight, Ingenuity has made 14 more flights for a total of 15 powered flights on another planet.[10][11]

The rover's goals include identifying ancient Martian environments capable of supporting life, seeking out evidence of former microbial life existing in those environments, collecting rock and soil samples to store on the Martian surface, and testing oxygen production from the Martian atmosphere to prepare for future crewed missions.[12]

Mission

Science objectives

The Perseverance rover has four main science objectives[13] that support the Mars Exploration Program's science goals:[12]

- Looking for habitability: identify past environments that were capable of supporting microbial life.

- Seeking biosignatures: seek signs of possible past microbial life in those habitable environments, particularly in specific rock types known to preserve signs over time.

- Caching samples: collect core rock and regolith ("soil") samples and store them on the Martian surface.

- Preparing for humans: test oxygen production from the Martian atmosphere.

In the first science campaign Perseverance performs an arching drive southward from its landing site to the Séítah unit to perform a "toe dip" into the unit to collect remote-sensing measurements of geologic targets. After that it will return to the Crater Floor Fractured Rough to collect the first core sample there. Passing by the Octavia B. Butler landing site concludes the first science campaign.

The second campaign will include several months of travel towards the "Three Forks" where Perseverance can access geologic locations at the base of the ancient delta of Neretva river, as well as ascend the delta by driving up a valley wall to the northwest.[14]

History

Despite the high-profile success of the Curiosity rover landing in August 2012, NASA's Mars Exploration Program was in a state of uncertainty in the early 2010s. Budget cuts forced NASA to pull out of a planned collaboration with the European Space Agency which included a rover mission.[15] By the summer of 2012, a program that had been launching a mission to Mars every two years suddenly found itself with no missions approved after 2013.[16]

In 2011, the Planetary Science Decadal Survey, a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine containing an influential set of recommendations made by the planetary science community, stated that the top priority of NASA's planetary exploration program in the decade between 2013 and 2022 should be to begin a Mars Sample Return campaign, a three-mission project to collect, launch, and safely return samples of the Martian surface to Earth. The report stated that NASA should invest in a sample-caching rover as the first step in this effort, with the goal of keeping costs under US$2.5 billion.[17]

After the success of the Curiosity rover and in response to the recommendations of the decadal survey, NASA announced its intent to launch a new Mars rover mission by 2020 at the American Geophysical Union conference in December 2012.[18]

Though initially hesitant to commit to an ambitious sample-caching capability (and subsequent follow-on missions), a NASA-convened science definition team for the Mars 2020 project released a report in July 2013 that the mission should "select and store a compelling suite of samples in a returnable cache."[19]

Design

The Perseverance design evolved from its predecessor, the Curiosity rover. The two rovers share a similar body plan, landing system, cruise stage, and power system, but the design was improved in several ways for Perseverance. Engineers designed the rover wheels to be more robust than Curiosity's wheels, which have sustained some damage.[20] Perseverance has thicker, more durable aluminum wheels, with reduced width and a greater diameter, 52.5 cm (20.7 in), than Curiosity's 50 cm (20 in) wheels.[21][22] The aluminum wheels are covered with cleats for traction and curved titanium spokes for springy support.[23] The heat shield for the rover was made out of phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator (PICA), to allow it to withstand up to 2,400 °F (1,320 °C) of heat.[24] Like Curiosity, the rover includes a robotic arm, although Perseverance's arm is longer and stronger, measuring 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in). The arm hosts an elaborate rock-coring and sampling mechanism to store geologic samples from the Martian surface in sterile caching tubes.[25] There is also a secondary arm hidden below the rover that helps store the chalk-sized samples. This arm is known as the Sample Handling Assembly (SHA), and is responsible for moving the soil samples to various stations within the Adaptive Caching Assembly (ACA) on the underside of the rover. These stations include volume assessment, imaging, seal dispensing, and hermetic seal station, among others.[26] Owing to the small space in which the SHA must operate, as well as load requirements during sealing activities, the Sample Caching System "is the most complicated, most sophisticated mechanism that we have ever built, tested and readied for spaceflight."[27]

The combination of larger instruments, new sampling and caching system, and modified wheels makes Perseverance heavier, weighing 1,025 kg (2,260 lb) compared to Curiosity at 899 kg (1,982 lb)—a 14% increase.[29]

The rover's radioisotope thermoelectric power generator (MMRTG) has a mass of 45 kg (99 lb) and uses 4.8 kg (11 lb) of Plutonium-238 oxide as its power source. The natural decay of plutonium-238, which has a half-life of 87.7 years, gives off heat which is converted to electricity—approximately 110 watts at launch.[30] This will decrease over time as its power source decays.[30] The MMRTG charges two lithium-ion rechargeable batteries which power the rover's activities, and must be recharged periodically. Unlike solar panels, the MMRTG provides engineers with significant flexibility in operating the rover's instruments even at night, during dust storms, and through winter.[30]

The rover's computer uses the BAE Systems RAD750 radiation-hardened single board computer based on a ruggedized PowerPC G3 microprocessor (PowerPC 750). The computer contains 128 megabytes of volatile DRAM, and runs at 133 MHz. The flight software runs on the VxWorks Operating System, is written in C and is able to access 4 gigabytes of NAND non-volatile memory on a separate card.[31] Perseverance relies on three antennas for telemetry, all of which are relayed through craft currently in orbit around Mars. The primary Ultra High Frequency (UHF) antenna can send data from the rover at a maximum rate of two megabits per second.[32] Two slower X-band antennas provide communications redundancy.

Twin rover

JPL built a copy of the Perseverance; a twin rover used for testing and problem solving, OPTIMISM (Operational Perseverance Twin for Integration of Mechanisms and Instruments Sent to Mars), a vehicle system test bed (VSTB). It is housed at the JPL Mars Yard and is used to test operational procedures and to aid in problem solving should any issues arise with Perseverance.[33]

Mars Ingenuity helicopter experiment

The Ingenuity helicopter, powered by solar-charged batteries, was sent to Mars in the same bundle with Perseverance. With a mass of 1.8 kg (4.0 lb), it demonstrated the possibility of flight in the rarefied Martian atmosphere and the potential usefulness of aerial scouting for rover missions. Its experimental test window was expected to last only about a month, but it successfully made flights that extended its mission for the remainder of 2021. It carries two cameras but no scientific instruments[34][35][36] and communicates with Earth via a base station onboard Perseverance.[37] The first takeoff was attempted on 19 April 2021 at 07:15 UTC, with livestreaming three hours later at 10:15 UTC confirming the flight.[38][39][40][41][42] It was the first powered flight by an aircraft on another planet.[9] Ingenuity made additional incrementally more ambitious flights, several of which were recorded by Perseverance's cameras.

Name

Associate Administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Thomas Zurbuchen selected the name Perseverance following a nationwide K-12 student "name the rover" contest that attracted more than 28,000 proposals. A seventh-grade student, Alexander Mather from Lake Braddock Secondary School in Burke, Virginia, submitted the winning entry at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In addition to the honor of naming the rover, Mather and his family were invited to NASA's Kennedy Space Center to watch the rover's July 2020 launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) in Florida.[43]

Mather wrote in his winning essay:

Curiosity. InSight. Spirit. Opportunity. If you think about it, all of these names of past Mars rovers are qualities we possess as humans. We are always curious, and seek opportunity. We have the spirit and insight to explore the Moon, Mars, and beyond. But, if rovers are to be the qualities of us as a race, we missed the most important thing. Perseverance. We as humans evolved as creatures who could learn to adapt to any situation, no matter how harsh. We are a species of explorers, and we will meet many setbacks on the way to Mars. However, we can persevere. We, not as a nation but as humans, will not give up. The human race will always persevere into the future.[43]

Mars transit

The Perseverance rover lifted off successfully on 30 July 2020, at 11:50:00 UTC aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas V launch vehicle from Space Launch Complex 41, at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) in Florida.[44]

The rover took about seven months to travel to Mars and made its landing in Jezero Crater on 18 February 2021, to begin its science phase.[45]

Landing

(February 2021)

The successful landing of Perseverance in Jezero Crater was announced at 20:55 UTC on 18 February 2021,[4] the signal from Mars taking 11 minutes to arrive at Earth. The rover touched down at 18°26′41″N 77°27′03″E / 18.4446°N 77.4509°E,[46] roughly 1 km (0.62 mi) southeast of the center of its 7.7 × 6.6 km (4.8 × 4.1 mi)[47] wide landing ellipse. It came down pointed almost directly to the southeast,[48] with the RTG on the back of the vehicle pointing northwest. The descent stage ("sky crane"), parachute and heat shield all came to rest within 1.5 km of the rover (see satellite image). The landing was more accurate than any previous Mars landing; a feat enabled by the experience gained from Curiosity's landing and the use of new steering technology.[47]

One such new technology is Terrain Relative Navigation (TRN), a technique in which the rover compares images of the surface taken during its descent with reference maps, allowing it to make last minute adjustments to its course. The rover also uses the images to select a safe landing site at the last minute, allowing it to land in relatively unhazardous terrain. This enables it to land much closer to its science objectives than previous missions, which all had to use a landing ellipse devoid of hazards.[47]

The landing occurred in the late afternoon, with the first images taken at 15:53:58 on the mission clock (local mean solar time).[49] The landing took place shortly after Mars passed through its northern vernal equinox (Ls = 5.2°), at the start of the astronomical spring, the equivalent of the end of March on Earth.[50]

The parachute descent of the Perseverance rover was photographed by the HiRISE high-resolution camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).[51]

Jezero Crater is a paleolake basin.[52][53] It was selected as the landing site for this mission in part because paleolake basins tend to contain perchlorates.[52][53] Astrobiologist Dr. Kennda Lynch's work in analog environments on Earth suggests that the composition of the crater, including the bottomset deposits accumulated from three different sources in the area, is a likely place to discover evidence of perchlorates-reducing microbes, if such bacteria are living or were formerly living on Mars.[52][53]

A few days after landing, Perseverance released the first audio recorded on the surface of Mars, capturing the sound of Martian wind[54][55]

Instruments

NASA considered nearly 60 proposals[56][57] for rover instrumentation. On 31 July 2014, NASA announced the seven instruments that would make up the payload for the rover:[58][59]

- Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE), an exploration technology investigation to produce a small amount of oxygen (O2) from Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). On 20 April 2021, 5.37 grams of oxygen were produced in an hour, with nine more extractions planned over the course of two Earth years to further investigate the instrument.[60] This technology could be scaled up in the future for human life support or to make the rocket fuel for return missions.[61][62]

- Planetary Instrument for X-Ray Lithochemistry (PIXL), an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer to determine the fine scale elemental composition of Martian surface materials.[63][64][65]

- Radar Imager for Mars' subsurface experiment (RIMFAX), a ground-penetrating radar to image different ground densities, structural layers, buried rocks, meteorites, and detect underground water ice and salty brine at 10 m (33 ft) depth. The RIMFAX is being provided by the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI).[66][67][68][69]

- Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer (MEDA), a set of sensors that measure temperature, wind speed and direction, pressure, relative humidity, radiation, and dust particle size and shape. It is provided by Spain's Centro de Astrobiología.[70]

- SuperCam, an instrument suite that can provide imaging, chemical composition analysis, and mineralogy in rocks and regolith from a distance. It is an upgraded version of the ChemCam on the Curiosity rover but with two lasers and four spectrometers that will allow it to remotely identify biosignatures and assess the past habitability. Los Alamos National Laboratory, the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology (IRAP) in France, the French Space Agency (CNES), the University of Hawaii, and the University of Valladolid in Spain cooperated in the SuperCam's development and manufacture.[71][72]

- Mastcam-Z, a stereoscopic imaging system with the ability to zoom.[73][74] Many photos were included in the published NASA photogallery. (Including Raw)

- Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals (SHERLOC), an ultraviolet Raman spectrometer that uses fine-scale imaging and an ultraviolet (UV) laser to determine fine-scale mineralogy and detect organic compounds.[75][76]

There are additional cameras and two audio microphones (the first working microphones on Mars), that will be used for engineering support during landing,[77] driving, and collecting samples.[78][79] For a full look at Perseverance's components look at Learn About the Rover.

- Wie es funktioniert

Traverse

Perseverance is planned to visit the bottom and upper parts of the 3.4 to 3.8 billion-year-old Neretva Vallis delta, the smooth and etched parts of the Jezero Crater floor deposits interpreted as volcanic ash or aeolian airfall deposits, emplaced before the formation of the delta; the ancient shoreline covered with Transverse Aeolian Ridges (dunes) and mass wasting deposits, and finally, it is planned to climb onto the Jezero Crater rim.[81]

In its progressive commissioning and tests, Perseverance made its first test drive on Mars on 4 March 2021. NASA released photographs of the rover's first wheel tracks on the Martian soil.[82]

Samples cached for the Mars sample-return mission

In support of the Mars sample-return mission, soil samples are being cached by Perseverance. Currently, out of 43 sample tubes, soil sample tubes cached: 5,[83] gas sample tubes cached: 1,[84] witness tubes cached: 1,[85] tubes due to be cached: 36. Before launch, 5 of the 43 tubes were designated “witness tubes” and filled with materials that would capture particulates in the ambient environment of Mars.[86]

Cost

NASA plans to invest roughly US$2.75 billion in the project over 11 years, including US$2.2 billion for the development and building of the hardware, US$243 million for launch services, and US$291 million for 2.5 years of mission operations.[8][87]

Adjusted for inflation, Perseverance is NASA's sixth-most expensive robotic planetary mission, though it is cheaper than its predecessor, Curiosity.[88] Perseverance benefited from spare hardware and "build-to print" designs from the Curiosity mission, which helped reduce development costs and saved "probably tens of millions, if not 100 million dollars" according to Mars 2020 Deputy Chief Engineer Keith Comeaux.[89]

Commemorative artifacts

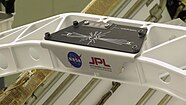

"Send Your Name to Mars"

NASA's "Send Your Name to Mars" campaign invited people from around the world to submit their names to travel aboard the agency's next rover to Mars. 10,932,295 names were submitted. The names were etched by an electron beam onto three fingernail-sized silicon chips, along with the essays of the 155 finalists in NASA's "Name the Rover" contest. The first name to be engraved was "Angel Santos".[citation needed] The three chips share space on an anodized plate with a laser engraved graphic representing Earth, Mars, and the Sun. The rays emanating from the Sun contain the phrase "Explore As One" written in Morse code.[90] The plate was then mounted on the rover on 26 March 2020.[91]

(26 March 2020)

(28 February 2021)

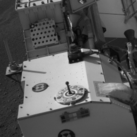

Geocaching in Space Trackable

Part of Perseverance's cargo is a geocaching trackable item viewable with the SHERLOC's WATSON camera.[92]

In 2016, NASA SHERLOC co-investigator Dr. Marc Fries — with help from his son Wyatt — was inspired by Geocaching's 2008 placement of a cache on the International Space Station to set out and try something similar with the rover mission. After floating the idea around mission management, it eventually reached NASA scientist Francis McCubbin, who would join the SHERLOC instrument team as a collaborator to move the project forward. The Geocaching inclusion was scaled-down to a trackable item that players could search for from NASA camera views and then log on to the site.[93] In a manner similar to the "Send Your Name to Mars" campaign, the geocaching trackable code was carefully printed on a one-inch, polycarbonate glass disk serving as part of the rover's calibration target. It will serve as an optical target for the WATSON imager and a spectroscopic standard for the SHERLOC instrument. The disk is made of a prototype astronaut helmet visor material that will be tested for its potential use in manned missions to Mars. Designs were approved by the mission leads at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), NASA Public Affairs, and NASA HQ, in addition to Groundspeak Geocaching HQ.[94][95]

Tribute to healthcare workers

Perseverance launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, which began to affect the mission planning in March 2020. To show appreciation for healthcare workers who helped during the pandemic, an 8 cm × 13 cm (3.1 in × 5.1 in) plate with a staff-and-serpent symbol (a Greek symbol of medicine) was placed on the rover. The project manager, Matt Wallace, said he hoped that future generations going to Mars would be able to appreciate healthcare workers during 2020.[96]

Family portrait of NASA Mars rovers

One of the external plates of Perseverance includes a simplified representation of all previous NASA Martian rovers, Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, as well as Perseverance and Ingenuity, similar to the trend of automobile window decals used to show a family's makeup.[97]

NASA outreach to students

In December 2021, the NASA team announced a program to students who have persevered with academic challenges. Those nominated will be rewarded with a personal message beamed back from Mars by the Perseverance rover.

(9 December 2021)

Media, cultural impact, and legacy

Parachute with coded message

The orange-and-white parachute used to land the rover on Mars contained a coded message that was deciphered by Twitter users. NASA's systems engineer Ian Clark used binary code to hide the message "dare mighty things" in the parachute color pattern. The 70-foot-wide parachute consisted of 80 strips of fabric that form a hemisphere-shape canopy, and each strip consisted of four pieces. Dr. Clark thus had 320 pieces with which to encode the message. He also included the GPS coordinates for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's headquarters in Pasadena, California (34°11’58” N 118°10’31” W). Clark said that only six people knew about the message before landing. The code was deciphered a few hours after the image was presented by Perseverance's team.[98][99][100]

"Dare mighty things" is a quote attributed to U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt and is the unofficial motto of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[101] It adorns many of the JPL center's walls.

Gallery

(February 2021)

R210 is the rover position on sol 210;

H163

1, H174

2 and H193

3 means 1st, 2nd and 3rd landing sites of Ingenuity on the Field H on sols 163, 174 and 193 respectively

Notes

See also

References

- ^ "Where is Perseverance?". Mars 2020 Mission Perseverance Rover. NASA. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ Landers, Rob (17 February 2021). "It's landing day! What you need to know about Perseverance Rover's landing on Mars". Florida Today. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Launch Windows". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b mars.nasa.gov. "Touchdown! NASA's Mars Perseverance Rover Safely Lands on Red Planet". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (19 February 2021). "Perseverance's Pictures From Mars Show NASA Rover's New Home – Scientists working on the mission are eagerly scrutinizing the first images sent back to Earth by the robotic explorer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ NASA's Perseverance Drives on Mars' Terrain for First Time Archived 6 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine NASA, 2021-03-05.

- ^ Staff (5 March 2021). "Welcome to 'Octavia E. Butler Landing'". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Mars Perseverance Landing Press Kit" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (19 April 2021). "NASA's Mars Helicopter Achieves First Flight on Another World - The experimental Ingenuity vehicle completed the short but historic up-and-down flight on Monday morning". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "After Six Months On Mars, NASA's Tiny Helicopter Is Still Flying High". NDTV.com. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ Wall, Mike (9 November 2021). "Mars helicopter Ingenuity aces 15th Red Planet flight". Space.com. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Overview". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Objectives". 2020 Mission Perseverance Rover. NASA. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Perseverance’s First Road Trip

- ^ "Europe To Press Ahead with ExoMars Plans Without NASA". SpaceNews. 13 February 2012.

- ^ Kremer, Ken (11 February 2012). "Budget Axe to Gore America's Future Exploration of Mars and Search for Martian Life". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Vision and Voyages for Planetary Science in the Decade 2013–2022. National Research Council. 7 March 2011. doi:10.17226/13117. ISBN 978-0-309-22464-2. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Wall, Mike (4 December 2012). "NASA to Launch New Mars Rover in 2020". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Mustard, J.F.; Adler, M.; Allwood, A.; et al. (1 July 2013). "Report of the Mars 2020 Science Definition Team" (PDF). Mars Exploration Program Anal. Gr. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (19 August 2014). "Curiosity wheel damage: The problem and solutions". planetary.org. The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Wehner, Mike (7 April 2020). "NASA's Perseverance rover got some sweet new wheels". BGR. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Mars 2020 – Body: New Wheels for Mars 2020". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Mars 2020 Rover – Wheels". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Meyer, Mal (19 February 2021). "Biddeford company creates critical part for Mars rover 'Perseverance' to land safely". WGME. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Mars 2020 Rover's 7-Foot-Long Robotic Arm Installed". mars.nasa.gov. 28 June 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

The main arm includes five electrical motors and five joints (known as the shoulder azimuth joint, shoulder elevation joint, elbow joint, wrist joint and turret joint). Measuring 7 feet (2.1 meters) long, the arm will allow the rover to work as a human geologist would: by holding and using science tools with its turret, which is essentially its hand.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Inside Perseverance: How Maxar Robotics Will Enable a Historic Mars…".

- ^ "The Extraordinary Sample-Gathering System of NASA's Perseverance Mars". 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Staff (2021). "Messages on Mars Perseverance Rover". NASA. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "NASAfacts: Mars 2020/Perseverance" (PDF). 26 July 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Mars 2020 Rover Tech Specs". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Prototyping an Onboard Scheduler for the Mars 2020 Rover" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Communications". NASA. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Amanda Kooser (5 September 2020). "NASA's Perseverance Mars rover has an Earth twin named Optimism". C/Net. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Mars mission readies tiny chopper for Red Planet flight". BBC News. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth. "A Helicopter on Mars? NASA Wants to Try". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Gush, Loren (11 May 2018). "NASA is sending a helicopter to Mars to get a bird's-eye view of the planet – The Mars Helicopter is happening, y'all". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Volpe, Richard. "2014 Robotics Activities at JPL" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ First Flight of the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter: Live from Mission Control. NASA. 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Work Progresses Toward Ingenuity's First Flight on Mars". NASA Mars Helicopter Tech Demo. NASA. 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Mars Helicopter completed full-speed spin test". Twitter. NASA. 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Mars Helicopter Tech Demo". Watch Online. NASA. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Mccurdy, Christen (17 April 2021). "Mars Ingenuity flight scheduled for Monday, NASA says". Mars Daily. ScienceDaily. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Name the Rover". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (30 July 2020). "NASA's newest Mars rover begins its journey to hunt for alien life". nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "Mission Timeline > Cruise". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Perseverance Rover Landing Site Map". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Mehta, Jatan (17 February 2021). "How NASA Aims to Achieve Perseverance's High-Stakes Mars Landing". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Al Chen (26:11) (22 February 2021). "NASA Press Conference Transcript February 22: Perseverance Rover Searches for Life on Mars". Rev. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ NASA/JPL-Caltech (18 February 2021). "Images from the Mars Perseverance Rover – Mars Perseverance Sol 0: Front Left Hazard Avoidance Camera (Hazcam)". mars.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (28 January 2021). "Coming Soon: Perseverance Sol 0". Patreon.

- ^ "HiRISE Captured Perseverance During Descent to Mars". NASA. 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Smith, Yvette (2021-02-02). "Astrobiologist Kennda Lynch Uses Analogs on Earth to Find Life on Mars" Archived 1 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. NASA. Retrieved 2021-03-02.

- ^ a b c Daines, Gary (2020-08-14). "Season 4, Episode 15 Looking For Life in Ancient Lakes". Archived 19 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine Gravity Assist. NASA. Podcast. Retrieved 2021-03-02.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (23 February 2021). "NASA shares first video and audio, new images from Mars Perseverance rover". CNN. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Crane, Leah (22 February 2021). "Perseverance rover has sent back stunning video and audio from Mars". New Scientist. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (21 January 2014). "NASA Receives Mars 2020 Rover Instrument Proposals for Evaluation". NASA. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Timmer, John (31 July 2014). "NASA announces the instruments for the next Mars rover". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne (31 July 2014). "Release 14-208 – NASA Announces Mars 2020 Rover Payload to Explore the Red Planet as Never Before". NASA. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne (31 July 2014). "NASA Announces Mars 2020 Rover Payload to Explore the Red Planet as Never Before". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Potter, Sean (21 April 2021). "NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover Extracts First Oxygen from Red Planet". NASA. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). "Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE)". techport.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Hecht, M.; Hoffman, J.; Rapp, D.; McClean, J.; SooHoo, J.; Schaefer, R.; Aboobaker, A.; Mellstrom, J.; Hartvigsen, J.; Meyen, F.; Hinterman, E. (2021). "Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE)". Space Science Reviews. 217 (1): 9. Bibcode:2021SSRv..217....9H. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00782-8. ISSN 0038-6308. S2CID 106398698. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Webster, Guy (31 July 2014). "Mars 2020 Rover's PIXL to Focus X-Rays on Tiny Targets". NASA. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Adaptive sampling for rover x-ray lithochemistry" (PDF). David Ray Thompson. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014.

- ^ Allwood, Abigail C.; Wade, Lawrence A.; Foote, Marc C.; Elam, William Timothy; Hurowitz, Joel A.; Battel, Steven; Dawson, Douglas E.; Denise, Robert W.; Ek, Eric M.; Gilbert, Martin S.; King, Matthew E. (2020). "PIXL: Planetary Instrument for X-Ray Lithochemistry". Space Science Reviews. 216 (8): 134. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..134A. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00767-7. ISSN 0038-6308. S2CID 229416825. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "RIMFAX, The Radar Imager for Mars' Subsurface Experiment". NASA. July 2016. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Chung, Emily (19 August 2014). "Mars 2020 rover's RIMFAX radar will 'see' deep underground". cbc.ca. Canadian Broadcasting Corp. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ "University of Toronto scientist to play key role on Mars 2020 Rover Mission". Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Hamran, Svein-Erik; Paige, David A.; Amundsen, Hans E. F.; Berger, Tor; Brovoll, Sverre; Carter, Lynn; Damsgård, Leif; Dypvik, Henning; Eide, Jo; Eide, Sigurd; Ghent, Rebecca (2020). "Radar Imager for Mars' Subsurface Experiment—RIMFAX". Space Science Reviews. 216 (8): 128. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..128H. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00740-4. ISSN 0038-6308.

- ^ "In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ "NASA Administrator Signs Agreements to Advance Agency's Journey to Mars". NASA. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Manrique, J. A.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Cousin, A.; Rull, F.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R. C.; Madsen, M. B.; Madariaga, J. M.; Gasnault, O.; Aramendia, J.; Arana, G. (2020). "SuperCam Calibration Targets: Design and Development". Space Science Reviews. 216 (8): 138. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..138M. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00764-w. ISSN 0038-6308. PMC 7691312. PMID 33281235.

- ^ Kinch, K. M.; Madsen, M. B.; Bell, J. F.; Maki, J. N.; Bailey, Z. J.; Hayes, A. G.; Jensen, O. B.; Merusi, M.; Bernt, M. H.; Sørensen, A. N.; Hilverda, M. (2020). "Radiometric Calibration Targets for the Mastcam-Z Camera on the Mars 2020 Rover Mission". Space Science Reviews. 216 (8): 141. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..141K. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00774-8. ISSN 0038-6308.

- ^ Bell, J. F.; Maki, J. N.; Mehall, G. L.; Ravine, M. A.; Caplinger, M. A.; Bailey, Z. J.; Brylow, S.; Schaffner, J. A.; Kinch, K. M.; Madsen, M. B.; Winhold, A. (2021). "The Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover Mast Camera Zoom (Mastcam-Z) Multispectral, Stereoscopic Imaging Investigation". Space Science Reviews. 217 (1): 24. Bibcode:2021SSRv..217...24B. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00755-x. ISSN 0038-6308. PMC 7883548. PMID 33612866.

- ^ Webster, Guy (31 July 2014). "SHERLOC to Micro-Map Mars Minerals and Carbon Rings". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "SHERLOC: Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals, an Investigation for 2020" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Microphones on Mars 2020". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (15 July 2016). "New Mars 2020 rover will be able to "hear" the Red Planet". cnn.com. CNN News. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Maki, J. N.; Gruel, D.; McKinney, C.; Ravine, M. A.; Morales, M.; Lee, D.; Willson, R.; Copley-Woods, D.; Valvo, M.; Goodsall, T.; McGuire, J. (2020). "The Mars 2020 Engineering Cameras and Microphone on the Perseverance Rover: A Next-Generation Imaging System for Mars Exploration". Space Science Reviews. 216 (8): 137. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..137M. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00765-9. ISSN 0038-6308. PMC 7686239. PMID 33268910.

- ^ "Sounds of Perseverance Mars Rover Driving – Sol 16 (16 minutes)". nasa.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Erik Klemetti (18 February 2021). "Jezero Crater: Perseverance rover will soon explore geology of ancient crater lake". Astronomy.com. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov (5 March 2021). "Perseverance Is Roving on Mars – NASA's Mars Exploration Program". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "3rd soil sample tube cached". nasa.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov. "NASA's Perseverance Plans Next Sample Attempt". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Sample Caching Dry Run, 1st sample tube cached". Twitter. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov. "Perseverance Sample Tube 266". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Cost of Perseverance". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "The Cost of Perseverance, in Context". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Answering Your (Mars 2020) Questions: Perseverance vs. Curiosity Rover Hardware". TechBriefs. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover (official account) [@NASAPersevere] (30 March 2020). "Some of you spotted the special message I'm carrying to Mars along with the 10.9+ million names you all sent in. "Explore As One" is written in Morse code in the Sun's rays, which connect our home planet with the one I'll explore. Together, we persevere" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "10.9 Million Names Now Aboard NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover". Mars Exploration Program. NASA. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "5 Hidden Gems Are Riding Aboard NASA's Perseverance Rover". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Geocaching on Mars: An Interview with NASA's Dr. Francis McCubbin". Geocaching Official Blog. 9 February 2021. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Geocaching and NASA head to Mars with the Perseverance Rover". Geocaching Official Blog. 28 July 2020. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "NASA's Perseverance rover to test future spacesuit materials on Mars". collectSpace. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Wall, Mike (17 June 2020). "NASA's next Mars rover carries tribute to healthcare workers fighting coronavirus". space.com. SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Weitering, Hanneke (25 February 2021). "NASA's Perseverance rover on Mars is carrying an adorable 'family portrait' of Martian rovers". Space.com. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Mars rover's giant parachute carried a secret message". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "'Dare mighty things': hidden message found on Nasa Mars rover parachute". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "NASA Sent a Secret Message to Mars. Meet the People Who Decoded It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore. "Dare mighty things". Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ updated from the map „Where is the rover”

External links

- Mars 2020 and Perseverance rover official site at NASA

- Mars 2020: Overview (2:58; 27 July 2020; NASA) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: LAUNCH of Rover (6:40; 30 July 2020) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: LAUNCH of Rover (1:11; 30 July 2020; NASA) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: LANDING of Rover (3:25; 18 February 2021; NASA) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: LANDING of Rover (3:55pm/et/usa, 18 February 2021

- Mars 2020 Perseverance Launch Press Kit

- Video: Mars Perseverance rover/Ingenuity helicopter report (9 May 2021; CBS-TV, 60 Minutes; 13:33)