Jean Joseph Marie Amiot

Jean Joseph Marie Amiot | |

|---|---|

Painting of Amiot | |

| Born | February 8, 1718 |

| Died | October 8, 1793 (aged 75) |

| Occupation | Jesuit missionary |

Jean Joseph Marie Amiot (Chinese: 錢德明; pinyin: Qián Démíng; February 8, 1718 – October 8, 1793) was a French Jesuit priest who worked in Qing China, during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

Born in Toulon, Amiot entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus at the age of 19. After he was ordained in 1746, he aspired to serve in an overseas mission. He was assigned a mission in China, and left France in 1749. He arrived at Beijing in 1751, and remained there for the rest of his life.

Amiot served as an intermediary between the academics of Europe and China. His correspondence provided insight on the culture of China to Europe. He translated Chinese works into French. His translation of Sun Tzu's The Art of War is the first translation of the work into a Western language.

Early life

Amiot was born in Toulon on February 8, 1718 to Louis Amiot, the royal notary of Toulon,[1] and Marie-Anne Serre. He was the eldest of ten children: five boys and five girls.[2] His brother Pierre-Jules-Roch Amiot would go on to become the lieutenant-general of the admiralty of Toulon.[3] His sister, Marguerite-Claire was an Ursuline sister.[4] Amiot maintained contact with both.[5]

After finishing his studies in philosophy and theology at the Jesuit seminary in Toulon, Amiot entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Avignon on September 27, 1737.[5] He remained a novice for two years.[5] Afterwards, he taught at the Jesuit colleges of Besançon, Arles, Aix-en-Provence, and finally at Nîmes, where he was professor of rhetoric in the academic year of 1744–1745. He completed his theological studies at Dôle from 1745 to 1748.[6] He was ordained as a priest on December 22, 1746.[6]

Arrival at China

Amiot requested Franz Retz, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus at that time, to serve in an overseas mission. He was given a mission to China.[7] In a letter to his brother, he had expressed his desire to serve in a mission to China.[8] He left France in 1749, accompanied by Chinese Jesuits Paul Liu and Stanislas Kang,[7] who were sent to study in France and were returning to their home country. Kang died at sea, before the party could reach China.[9]

They arrived at Macau on July 27, 1750.[7] The Jesuits of Beijing announced Amiot's arrival, along with Portuguese Jesuits José d'Espinha and Emmanuel de Mattos[7][10] to Emperor Qianlong, who ordered that they be taken to the capital.[11] On March 28, 1751, they left Macau for Guangzhou, and arrived five days later.[12] They left Canton on June 2, and arrived at Beijing on August 22.[13]

After his arrival, he was put in charge of the children's congregation of the Holy Guardian Angels. Alongside this, he studied the Chinese language.[11] He adopted the Chinese name Qian Deming (錢德明)[14] and wore Chinese clothing in order to adapt himself to Chinese culture.[15] In 1754, Amiot made a young Chinese man by the name of Yang Ya-Ko-Pe his assistant.[15] Amiot instructed him in the European manner. Yang died in 1784, after working with Amiot for over thirty years.[11]

Suppression of the Jesuits

In 1762 the Parliament of Paris ordered the suppression of the Society of Jesus and the confiscation of its property.[16] The society was abolished in France two years later, confirmed by King Louis XV.[17] The Jesuit mission in China survived for a while after their suppression, being protected by the Qianlong Emperor himself.[18] The final blow, however, would be Pope Clement XIV's brief, Dominus ac Redemptor. The brief reached the French Jesuits on September 22, 1775.[19] A German Carmelite named Joseph de Sainte-Thérèse brought the legal brief to the Jesuits.[20] The Jesuits of Beijing surrendered to the brief, resigned from the Society of Jesus, and became secular priests.[18][21] Wishing to keep the French mission alive, King Louis XVI sent financial aid to the mission and appointed François Bourgeois as the administrator of the French mission.[22][23] Amiot was named as Bourgeois' replacement.[24]

Amiot turned his attention to writing. He maintained contact with Henri Bertin, the foreign minister of France. His correspondences were published from 1776 to 1791 in the Mémoires concernant l’histoire, les sciences, les arts, les mœurs et les usages des Chinois.[25] He also corresponded with other European Academies, including brief contacts Imperial Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society.[26]

Later life and death

Amiot's health gradually worsened; the development of the French revolution distressed him.[27] He was too ill to meet George Macartney's embassy.[28] Instead, he sent Macartney his portrait and a letter.[29] On October 8, 1793, the news of King Louis XVI's death reached Amiot. He celebrated Mass for the deceased king, and visited the tombs of the Jesuits. He died on that same night.[26]

Works

In 1772 Amiot's translation of Sun Tzu's The Art of War was published. It includes a translation of the Yongzheng Emperor's Ten Precepts. This translation is the first translation of The Art of War in the West. The next translation of the work in a Western language would not be made until Everard Calthrop published his translation of the work in English in 1905.[30]

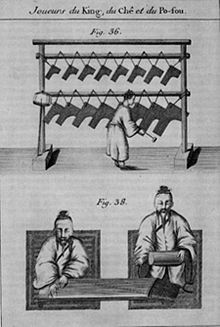

Amiot sent his translation of Li Guangdi's Guyue Jingzhuan (古樂經傳) to Paris in 1754.[31] He later acknowledged that the translation contained errors and was incomplete.[32] The translation was referenced by Jean-Philippe Rameau it in his treatises.[33] Amiot's own work on Chinese music, Mémoire sur la musique des Chinois was published twice by Pierre-Joseph Roussier in 1779 and 1780.[34] Amiot's supplements to the work were not published until 1997.[35] Amiot also sent collections of Chinese music and instruments to France.[36] In 1777, he sent a Sheng, which contributed to the development of the harmonica in Europe.[37]

Amiot could play the harpsichord and the flute. He tried to win over Chinese listeners by playing pieces by French baroque composers, including Rameau's Les sauvages and Les cyclopes. These attempts were not successful.[38] When Amiot asked the Chinese musicians for their opinions, they remarked that "your music was not made for our ears, nor our ears for your music".[39] Lester Hu, assistant professor of musicology at the University of California, Berkeley has doubted the veracity of this story.[40]

Amiot could speak in Manchu, the language of the emperor.[41] He wrote a Manchu-French dictionary, which was published from 1789 to 1790 with the help of Bertin.[42] Prince Hongwu, a member of the imperial family, praised the dictionary.[43] Amiot also wrote a Manchu grammar, which was never published.[42]

Amiot carried out scientific observations and experiments while working in China. He made a record of the weather in Beijing, which was published by Charles Messier in 1774.[44] Amiot tried to build a hot air balloon, but was discouraged by Prince Hongwu, for fear of disseminating the discovery.[45]

Notes

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 6.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 225–226.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 226.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Rochemonteix 1915, p. 7.

- ^ a b Hermans 2019, p. 232.

- ^ a b c d Hermans 2019, p. 233.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 10.

- ^ Pfister 1932b, p. 861.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Pfister 1932a, p. 838.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 40.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 41.

- ^ Pfister 1932a, p. 837.

- ^ a b Hermans 2019, p. 236.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 99.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 251.

- ^ a b Marin 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 180.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, pp. 151, 193.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 194.

- ^ Marin 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 219.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 253.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 254.

- ^ a b Hermans 2019, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Rochemonteix 1915, p. 427.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 263.

- ^ Peyrefitte 1992, p. 158.

- ^ Dobson 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Irvine 2020, p. 33.

- ^ Davin 1961, p. 389.

- ^ Irvine 2020, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 258.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 259.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 260.

- ^ Chen et al. 2022, p. 237.

- ^ Irvine 2020, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Lindorff 2004, p. 411.

- ^ Hu 2021.

- ^ Davin 1961, p. 383.

- ^ a b Davin 1961, p. 388.

- ^ Statman 2017, p. 101.

- ^ Hermans 2019, p. 244.

- ^ Statman 2017, p. 108.

References

- Chen, Shouxiang; et al. (October 3, 2022). "The Art of Instrumental Music in the Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasties". In Li, Xifan (ed.). A General History of Chinese Art. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110790924.

- Davin, Emmanuel (1961). "Un éminent sinologue toulonnais du XVIIIe siècle, le R. P. Amiot, S. J. (1718-1793)". Bulletin de l'Association Guillaume Budé. 1 (3): 380–395. doi:10.3406/bude.1961.3962.

- Dobson, Sebastian (2013). "Lt.Col. E.F. Calthrop (1876–1915)". In Cortazzi, Hugh (ed.). Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits. Vol. 8. Brill. pp. 85–101. ISBN 9789004246461.

- Hermans, Michael (September 28, 2019). "Appendix 2 Amiot's Life". The Mandate of Heaven. Brill. pp. 224–274. doi:10.1163/9789004416215_009. ISBN 9789004416215.

- Hu, Zhuqing (Lester) S. (December 2021). "Chinese Ears, Delicate or Dull? Toward a Decolonial Comparativism". online.ucpress.edu. 74 (3): 501–569. doi:10.1525/jams.2021.74.3.501. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- Irvine, Thomas (2020). Listening to China: Sound and the Sino-Western Encounter, 1770-1839. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226667263.

- Lindorff, Joyce (2004). "Missionaries, Keyboards and Musical Exchange in the Ming and Qing Courts". Early Music. 32 (3): 403–414. doi:10.1093/em/32.3.403. ISSN 0306-1078.

- Marin, Catherine (2008). "La mission française de Pékin après la suppression de la compagnie de Jésus en 1773". Transversalités. 107 (3): 11–28. doi:10.3917/trans.107.0009.

- Peyrefitte, Alain (1992). The Immobile Empire. Translated by Rotschild, Jon. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780345803948.

- Pfister, Louis (1932a). "Le P. Jean-Joseph-Marie Amiot". Notices biographiques et bibliographiques sur les Jésuites de l'ancienne mission de Chine. 1552-1773 (in French). Imprimerie de la Mission catholique. pp. 837–860.

- Pfister, Louis (1932b). "Le Fr. Philippe-Stanislas Kang". Notices biographiques et bibliographiques sur les Jésuites de l'ancienne mission de Chine. 1552-1773 (in French). Imprimerie de la Mission catholique. pp. 861–862.

- Rochemonteix, Camille de (1915). Joseph Amiot et les derniers survivants de la mission française à Pékin (1750-1795). Paris: A. Picard et fils.

- Statman, Alexander (2017). "A Forgotten Friendship: How a French Missionary and a Manchu Prince Studied Electricity and Ballooning in Late Eighteenth Century Beijing". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (46): 89–118. ISSN 1562-918X.