Tamil Eelam

This article is currently subject to editing restrictions, following a dispute resolution consensus. Do not insert unreferenced text. Before changing anything that might be controversial, please report the issue at Wikipedia talk:WikiProject Sri Lanka Reconciliation. Please do not remove this message until the restrictions have been removed. |

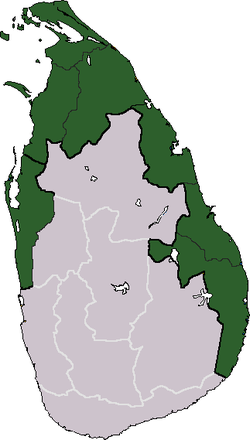

Tamil Eelam தமிழ் ஈழம் tamiḻ īḻam | |

|---|---|

Land area for Tamil Eelam | |

| Ethnic groups | Tamil |

| Area | |

• Total | [convert: invalid number] |

• Water (%) | negligible[citation needed] |

| Population | |

• 2001 census | 3,162,254[1] |

• Density | 162/km2 (419.6/sq mi) |

| |

Tamil Eelam ([தமிழீழம், tamiḻ īḻam] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), generally rendered outside Tamil-speaking areas as தமிழ் ஈழம[citation needed]) is the name given by certain Tamil groups in Sri Lanka to the state which they aspire to create in the north and east of Sri Lanka. The name is derived from the ancient Tamil name for island of Sri Lanka: Eelam. One Tamil militant group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who are a terrorist organisation banned in 31 countries including the United States, India,United Kingdom, European Union, Canada and Australia, ran a virtual mini-state in parts of the area, but is now confined to a 20 square kilometre strip of land in the Mullaithivu District on the north-eastern coast.[2]

Central issue and historic development

Great Britain gained control of the whole island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1815 and administratively unified the island[3] with a legislative council in 1833 with three Europeans and one each for Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamils and Burghers. British Governor William Manning, who arrived in Ceylon in 1919, created a reformed legislative council in 1921 and actively encouraged communal thinking in the legislative council.[4][5] As a result, the Tamils started to develop communal consciousness and began to think of themselves as needing to be represented by Tamil leadership.[4][6] It was this development that made way for the development of the Tamil political organization called the All Ceylon Tamil Congress headed by G. G. Ponnambalam.[7][8]

Ceylon achieved independence from the British in 1948 and in the same year the government of Sri Lanka, with the acceptance vote from G.G. Ponnambalam, passed a new act called the Ceylon Citizen Act which disenfranchised the Indian Tamil plantation workers[9][10][11] Though Ponnambalam did not vote for all the bills pertaining to the Ceylon citizenship act (including the offending bill), his silence in parliament made the Tamil public believe that he was not interested in Indian Tamil rights.[12] . In 1949 a new Tamil political party, named the Federal Party, was formed and was led by S. J. V. Chelvanayakam who earlier broke away from All Ceylon Tamil Congress because of the latter's decision to tie up with the UNP.[9]

In 1956 the government enacted another act called the Official Language Act (better known as the Sinhala Only Act) which made the Sinhala as the sole official language of Sri Lanka.[10][13] The Ceylon Citizen Act and the Sinhala Only Act were seen as discriminatory policies towards the minorities and led to increased ethnic and political tensions between the two communities. The Federal Party (FP) opposed both the Ceylon Citizenship Act and the Sinhala Only Act and as a result became popular amongst the Tamil population[10][14] . As a result of their popularity the Federal party became the most dominant party in the Tamil districts after the 1956 elections.

Concept

Federal Party (FP) became the most dominant Tamil political party in 1956 and it lobbied for a unitary state which gave Tamil and Sinhalese equal rights, including recognition of two official languages (Tamil and Sinhala) and considerable autonomy for the Tamil areas.[15][16] It was against this backdrop that the Federal party decided to sign the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam pact on July 1957. However soon afterwards, the agreement was not implemented by the Sinhala party. On 1965 another pact called Dudey-Chelvanayakam pact was also signed but was also not implemented.[17] The failure of the Sinhalese dominated government to implement devolutionary agreements through the 1950s and 1960s, abrogation of power-sharing promises, worsening economic conditions, and lack of territorial autonomy caused further disillusionment and isolation among northern Tamils.[18]

In the 1970 election the United Front (UF) led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike came into power. The new Government in power adapted two new policies that were considered discriminatory by the Tamil people.[19]First the government introduced a dicriminatory system regulating university admissions specifically targeted at reducing the intake of overachieving Tamils and other minorities in the Sri Lankan educational system. The scheme allotted up to 40% of the university placement to rural youth (primarily from Sinhala areas). The government claimed that this was an affirmative action scheme to assist geographically disadvantaged students to gain tertiary education. According to K.M. de Silva, a historian, the system of standardisation of marks, however, required the Tamil students to achieve higher marks than the Sinhalese students to get into university.[3][20] Same sort of policy was adapted for employment in the public sector in which less than 10 percent of Tamil speakers were employed as public servants.[19][21] The Federal Party opposed these policies and Chelvanayakam resigned his parliamentary seat on October 1972. The new constitution in 1972 further exasperated long standing grievances and sense of discrimination for the Sri Lankan Tamil people. This had emboldened younger Tamils to seek ways to form a Tamil homeland (nation) where the rights and freedoms of the Tamil people could be protected and nurtured.[18]

In 1973, Tamil parties' call for regional autonomy was replaced with the demand for a separate state called Tamil Eelam and two years later, in 1975, all Tamil political parties merged together and became known as the Tamil United Liberation Front(TULF). On 1976, the first national convention of the Tamil United Liberation Front was held at Vaddukodai and the Tamil United Liberation Front adapted a unanimous resolution called the Vaddukodai resolution. The Vaddukodai resolution charged that the Sinhalese government, with the use of the constitution of 1972, used its power to "deprive the Tamil nation of its territory, language, citizenship, economic life, opportunities of employment and education thereby destroying all the attributes of nationhood of the Tamil people." The resolution further called for the "Free, Sovereign, Secular Socialist State of TAMIL EELAM".[22]

As a result of the Vaddukodai resolution, the Tamil United Liberation Front became the first Tamil political party to run its campaign on a separatist platform. It swept the parliamentary elections in the Tamil-dominated districts of the North and East in 1977, winning 18 seats and became the largest opposition in parliament.[23][24] The reason for the success of the TULF was seen as the result of growing Tamil agitation for self-determination.[18]

During the time of the Vaddukodai declaration, there were several Tamil militant organizations that believed an armed struggle was the only way to protect the sovereignty of the Tamil areas. TULF, however, believed in peaceful parliamentary ways towards achieving a solution.[25] Though the TULF had adapted a separatist platform they were still open for peaceful negotiations and, as a result, decided to work towards a political agreement with the executive president at that time, J.R Jayewardene. The outcome was the District Development Councils' scheme (DDC) passed 1980. The District Development Councils' scheme was based, to some extent, on decentralization of the government within a united Sri Lanka. The District Development Councils' scheme was soon abandoned because both sides were not able to agree to the number District Ministership in the Tamil districts.[26] In 1983 the Sixth Amendment was passed and required Tamil members of parliament and Tamils in public office to take the oath of allegiance to the unitary state of Sri Lanka. The Sixth Amendment forbade advocating a separate state even by peaceful means. Consequently, the TULF was expelled from the parliament for refusing to take the oath.[27]

Development

At first, the concept of Tamil Eelam conceived by the Federal party was a state within a united Sri Lanka, but in time the concept developed into complete self-determination. The concept of Tamil Eelam always implied the notion of freedom and self-government for the Tamil people[28] The demand for a separate statehood of Tamil Eelam is believed to have grown as a result of job opportunities and university admissions being severely curtailed for Tamils because of discriminatory government quotas; and continuing decline of economic opportunities[22] As a result the people began to believe that a separate state would win back their opportunities and the concept of Tamil Eelam was welcomed enthusiastically throughout Tamil areas[29] In addition to the economical and social basis for separate state there is also a more fundamental basis for support for a separate statehood - safety[30] In 1977, after the parliamentary election campaign by the TULF which was on a platform of separate state, a riot engulfed the island in which about 300 Tamil civilians were killed[16] Likewise in 1983, another anti-Tamil riot engulfed the island as a result of an IED attack on group of Sri Lankan Soldiers by LTTE rebels. The riot, known as Black July, killed between 1,000[31] and 3,000[32] The call for Tamil Eelam increased as a result of this violence against the Tamil minority perpetrated by the Sinhalese majority[16] Furthermore, allegations of state terrorism and genocide committed by the Sri Lankan government have led to solidification of demand for a separate state for minority Tamils[33][34][35] To add to the Tamil people's separatist sentiments, acts of mass violence, rape, extrajudicial executions, whole scale round ups, forced detention, torture and other forms of inhuman treatment by members of Sinhalese dominated Sri Lankan security forces within the North and East provinces have further created communal tensions among the Tamil people[16] The mistrust in the Sinhala dominated armed forces and the perceived discrimination faced by the Tamil population[36] lead the Tamil people to believe that only Eelam could provide long term safety[18] and came to believe that their very survival was possible only through formation of a separate Tamil state on the island[30]

Current status

Governance

This article needs to be updated. |

The portion of Northern Sri Lanka under the control of the LTTE was run as a de facto quasi-independent state[37][38][39] and it runs a government[40][41][42] in these areas. The Tamil Tigers have also established a military wing[43][44][45] with land combat force, naval force (the Sea Tigers), air wing which they call "Tamil Eelam Air Force",[46] In addition, the LTTE ran a judicial system complete with local, supreme and high courts. The US state department has alleged that the judges had very little standards or training and act as agents to LTTE; it also accuses the LTTE of forcing Tamils under their control to accept their judicial system[47], however, people who have a choice at judicial system sometimes choose to go to the judicial courts of the areas controlled by the LTTE rather than the Sri Lankan courts[24][40][41][42]. Furthermore, Tigers performs state functions such as Police Force, Human Rights organization, humanitarian assistant board[40], health board and education board[41][48][49]. It also ran a Bank (Bank of Tamil Eelam), a radio station (Voice of Tigers) and a Television station (National Television of Tamil Eelam)[42]

Following the Sri Lankan Army's capture of the claimed LTTE administrative capital Kilinochchi[50] on January 2, 2009, the LTTE's administration system has been believed to be dismantled, yet they continue to run their website, radio telecasts. This information is reaching the Tamil diaspora in Britain, Australia and Canada. [51].

Pongu Tamil

Pongu Tamil (or Tamil Uprising) is an event that is held in support of "Tamils Right to Self-Determination" and "Tamil Traditional homeland". Pongu Tamil was first organized in Jaffna on January 2001 by students of the Jaffna University. The event was organized in response to alleged disappearances, mass graves and abuses under the government's military rule and was designed as peaceful protest. The event attracted between 4000-5000 students amid the event being banned in Jaffna, an area controlled by the Sri Lankan Army, and allegations of intimidation and death threats by the police.[52] In 2003, the event was held again and attracted over 150,000 people and has become an annual event in the LTTE held areas of Sri Lanka. In the recent years some members of Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora have also picked up on the notion and it has become an annual event in the countries they reside.[37] In 2008, the event was held in New Zealand, Norway, Denmark, Italy, South Africa, France, Australia, England and Canada. According to Tamilnet, a pro-rebel website, the event attracted thousands of people in these countries including over 7,000 in France[53], 30,000 in England [54] and over 75,000 in Canada.[55] Australia is said to have attracted about 2000 people displayed the Australian flag, Tiger symbol and picture of Velupillai Prabhakaran.[56]

Support

The level of support for the movement within Sri Lanka is difficult to assess, however several individuals and groups across the world support the right to self-determination of the Tamils in an autonomous region of Tamil Eelam.[citation needed]

Lee Kuan Yew said of the movement

The country [Ceylon] will never be put together again. Somebody should have told them - change the system, loosen up, or break off. And looking back, I think the Tunku was wise. (The reference is to Tunku Abdul Rahman the Malaysian Prime Minister under whose rule Singapore separated from Malaysia). I offered a loosening up of the system. He said: "Clean cut, go your way". Had we stayed in, and I look at Colombo and Ceylon, I mean changing names, sometimes maybe you deceive the gods, but I don't think you are deceiving the people who live in them. It makes no great difference to the tragedy that is being enacted. They failed because they had weak or wrong leaders."[57]

Virginia Judge, who visited the North East area noted that in a three year period Tamils had developed a virtual state within a state. She has stated she supports a genuine federal Tamil Eelam that guarantees the right of the Tamil minority to autonomy so their culture is protected and they enjoy full economic and political rights. She has voiced support to a federal structure with equity and self determination for the Tamil people.[58] The MP John Murphy stated that the targeting of Tamil civilians by the Sri Lankan Government's forces in airstrikes "clearly demonstrates that it does not regard the Tamil people to be part of its population." It strengthened his support for the Tamil people's case for self determination.[59] In 2008, he handed a petition of 4000 signatories to the Australian House of Representatives accusing the Government of Sri Lanka of being guilty of the crime of genocide, supporting the Tamil right to self-determination.[60]

A 1981 resolution adopted by the US Massachusetts House of Representatives called for the restoration and reconstitution of the separate sovereign state of Tamil Eelam, supporting the right to self-determination of the Tamils of Eelam.[61]

The ANC of the Government of South Africa, noting in January 2009 that the continued conflict on the island has been cited on international monitoring mechanisms as reaching genocidal proportions described the conflict as a liberation war between the Tamil Tigers for self determination and the Sri Lankan Government that had led to the deaths of thousands of lives, and called for an end to hostilities and a political solution.[62] Willis Mchunu of the state legislature of KwaZulu-Natal condemned the genocide of Tamils and expressed support to the Tamil struggle for freedom. Mtandeni Dlungwana, leader of the province's branch of the African National Congress Youth League stated they were fully backing the Tamil Eelam struggle.[63]

British Tamils Forum, a conglomeration of British Tamil diaspora organizations states as its aim to "highlight the humanitarian crises and human rights violations perpetrated by the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL), and to advance the Tamil national cause through democratic means."[64] The forum has garnered recognition and appraisal from several prominent figures in public life during its tenure. Annual political rallys are organised by the BTF and in June, July, September and October 2008, the forum organised and participated in several public demonstrations in London.[65] It worked in union with the NSSP, the TYO (Tamil Youth Organisation), S4P (Solidarity for Peace), the UK Socialist Party, International Socialist Group and South Asia Solidarity Group in supporting the right to self determination of the Tamil people in Tamil Eelam. All Party debates in UK Parliament have highlighted gatherings organised by the BTF and the issues the forum has raised.[66][67] The Norwegian Tamil Forum and related groups have organised similar protests in Norway with MP support for Tamil self-determination, as has the Canadian Tamil Congress in Canada.

A survey in late 2008 by the Tamil Nadu daily Ananda Vikatan found 55.4% of Indian Tamils in the state supported the separation of Tamil Eelam, while 34.63% supported a federal Tamil Eelam.

Other notable supporters of independence include politicians Vaiko and Thirumavalavan. Directors Bharathiraaja, Seeman and Ameer Sultan are strong advocates of the independence of Tamil Eelam. Bruce Fein, former associate deputy attorney general of Ronald Reagan, has condemned the actions of the Sri Lankan state against Tamils as genocide, strongly voicing support for the separation of Tamil Eelam under a UN referendum.[68][69] Muthukumar(Self-immolation of Muthukumar), a DTP operator for a Tamil magazine 'Penne Nee' doused himself with kerosene at the Regional Passport Office, Chennai,Tamilnadu, India and set himself on fire to highlight the Tamil plight.[70]

self-immolations for Tamil Eelam

1.Muthukumar(Self-immolation of Muthukumar)

2. Murugathasan [71]

3. Amaresan

[72]

4.Pallapatti Ravi

[73]

5.Gokularathinam

[74]

6.Tamilvendhan

[75]

7.Sivaprakasam [76]

8.Raja [77]

9.Ravichandran [78]

10.Ramu [79]

11.Sivanandam [80]

See also

- Eelam War IV

- Self-determination

- North Eastern Province, Sri Lanka

- Origins of the Sri Lankan civil war

- Policy of standardization

References

- ^ According to the 2001 Sri Lankan census, for all districts of North Eastern Province and Puttalam District in North Western Province.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b Stokke, K. (2000). "The Struggle for Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka". A Journal of Urban and Regional Policy. 3 (2): 285–304. doi:10.1111/0017-4815.00129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b K. M. de Sila, History of Sri Lanka, Penguin 1995 Cite error: The named reference "kms" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ K. M. de Silva, Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, vol 2(1), p 114 (1972)

- ^ K. M. de Silva, Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, vol 2(1), p 114 (1972)

- ^ Gunasingham, M.Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism: A study of its origins, p.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.1-12

- ^ a b "Missed Opportunities and the Loss of Democracy".

- ^ a b c De Silva, P.L. (1997). "The growth of Tamil paramilitary nationalisms: Sinhala Chauvinism and Tamil responses" (PDF). South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 20: 97–118. doi:10.1080/00856409708723306. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.66-81

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.80

- ^ Tambiah, S.J. Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy, p.

- ^ Tambiah, S.J. Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy, p.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.82-90

- ^ a b c d Kearney, R.N. (1985). "Ethnic Conflict and the Tamil Separatist Movement in Sri Lanka". Asian Survey. 25 (9): 898–917. doi:10.1525/as.1985.25.9.01p0303g. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.81-110

- ^ a b c d Kleinfeld, M. (2005). "Destabilizing the identity--territory nexus: Rights-based discourse in Sri Lanka's new political geography" (PDF). GeoJournal. 64 (4): 287–295. doi:10.1007/s10708-005-5806-0. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ a b Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p.102-103

- ^ De Silva, K.M. (1984). "University Admissions and Ethnic Tension in Sri Lanka, 1977—1982". From Independence to Statehood: Managing Ethnic Conflict in Six African and Asian States. London: Francis Pinter: 97.

- ^ Goldman, R.B. and Wilson, A.J. From Independence to Statehood, p.173-184

- ^ a b Pfaffenberger, B. (1981). "The Cultural Dimension of Tamil Separatism in Sri Lanka". Asian Survey. 21 (11): 1145–1157. doi:10.1525/as.1981.21.11.01p0322p. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ DBS Jeyaraj. "TULF leader passes away". Hindu News. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ a b Nadarajah, S. (2005). "Liberation struggle or terrorism? The politics of naming the ltte". Third World Quarterly. 26 (1): 87–100. doi:10.1080/0143659042000322928.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schalk, P. (2002). "Ilavar and Lankans, Emerging Identities in a Fragmented Island" (PDF). Asian Ethnicity. 3 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/14631360120095865. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. The Break-up of Sri Lanka: The Sinhalese-Tamil Conflict, p.142-143

- ^ Wilson, A.J. The Break-up of Sri Lanka: The Sinhalese-Tamil Conflict, p.228

- ^ Matthews, B. (1982). "District Development Councils in Sri Lanka". Asian Survey. 22 (11): 1117–1134. doi:10.1525/as.1982.22.11.01p04282. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. (1998). "The de facto state of Tamil Eelam". Wilson & Chandrakanthan, Demanding Sacrifice: War and Negotiation in Sri Lanka, London: Conciliation Resources.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gambetta, D. (2005). Making sense of suicide missions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780199276998.

- ^ "President Kumaratunga's speech on the 21st Anniversary of 'Black July'". South Asia Terrorism Portal. 2004-07-23.

- ^ BBC NEWS | South Asia | Twenty years on - riots that led to war

- ^ Rupesinghe, Ethnic Conflict in South Asia: The Case of Sri Lanka and the Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF), pp.337

- ^ Hattotuwa, From violence to peace: Terrorism and Human Rights in Sri Lanka, pp.11-13

- ^ "Sri Lanka: testimony to state terror". Race & Class. 26 (4). Institute of Race Relations: 71–84. 1985. doi:10.1177/030639688502600405.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Shastri, A. (1990). "The Material Basis for Separatism: The Tamil Eelam Movement in Sri Lanka". Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (1): 56–77. doi:10.2307/2058433. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ a b "SFrom relief, rehabilitation to peace". Retrieved 2008-06-21. Cite error: The named reference "sunday" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Independence-seeking Tigers already run shadow state". Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ "'War victory party' in Sri Lanka". Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ a b c Stokke, K. (2006). "Building the Tamil Eelam State: emerging state institutions and forms of governance in LTTE-controlled areas in Sri Lanka". Third World Quarterly. 27 (6): 1021–1040. doi:10.1080/01436590600850434.

- ^ a b c McConnell, D. (2008). "The Tamil people's right to self-determination" (PDF). Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 21 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1080/09557570701828592. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ a b c Ranganathan, M. (2002). "Nurturing a Nation on the Net: The Case of Tamil Eelam". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 8 (2): 51–66. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ Winn, N. (2004). Neo-Medievalism and Civil Wars. Frank Cass Publishers. p. 130.

- ^ Rizas, S. (2005). "Neo-medievalism and Civil Wars Neil Winn". Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 5 (1): 157.

- ^ McDowell, C. (1996). A Tamil Asylum Diaspora: Sri Lankan Migration, Settlement and Politics in Switzerland. Berghahn Books.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rowland Buerk. "Tamil Tigers unveil latest tactic". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ "US slams police, Karuna and LTTE". BBC News.

- ^ Goodhand, J. (2000). "Social Capital and the Political Economy of Violence: A Case Study of Sri Lanka". Disasters. 24 (4): 390–406. doi:10.1111/1467-7717.00155.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wilson, A. J. (1988). The Break-up of Sri Lanka: The Sinhalese-Tamil Conflict. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850650330.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ Orjuela, C. (2003). "Building Peace in Sri Lanka: a Role for Civil Society?". Journal of Peace Research. 40 (2): 195. doi:10.1177/0022343303040002004.

- ^ "Pongku Thamizh rally in France draws 7000". Tamilnet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ "Grand finale for Pongku Thamizh in London". Tamilnet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ "Spontaneous show of solidarity in Canada". Tamilnet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ "Tiger territory". 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ Fook Kwag, Han (1998). Lee Kuan Yew - The Man and his Ideas. Times Editions. ISBN 9789812040497.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Virginia Judge. "SRI LANKA CIVIL, POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC RIGHTS" (PDF). Parliamentary debates - Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ "Indiscriminate Attacks strengthen case for Tamil self-rule- Aussie MP". TamilNet. 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ "Australian parliamentarian calls for ceasefire". TamilNet. 2008-17-02. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Resolution of US Massachusetts House of Representatives Calling for the Restoration of the Separate Sovereign State of Tamil Eelam". TamilNation.org. 1981-06-18. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 56 (help) - ^ ""ANC urges immediate ceasefire between GoSL, LTTE, citing genocide"". TamilNet. January 29, 2009.

- ^ "KwaZulu condemns genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka". TamilNet. 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ^ "UK Tamils Forum Index Page". British Tamils Forum. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ "Diaspora Tamils seek solidarity with British Public". TamilNet. 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ British Tamils Forum. "President Rajapakse will think twice before visiting London next time - British Tamils Forum" (html). Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 14th October 2008". UKParliament.co.uk. 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ ""Fein: Hold Referendum to test support for Tamil statehood"". TamilNet. May 26, 2008.

- ^ ""Bruce Fein: U.S. declaration of independence validates Tamil statehood"". TamilNet. January 29, 2008.

Applying the 'self-evident' truths celebrated in the Declaration of Independence, the United States should recognize the right of Sri Lanka's long oppressed Tamil people to independent statehood from the racial supremacist Sinhalese... Fein argues, the history of the persecution of the Tamil people "easily justifies Tamil statehood, with boundaries to be negotiated," and points out, "The Declaration of Independence proclaims: "[W]hen a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a design to reduce [a people] under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security."

- ^ ""Suicide at Chennai passport office over Lanka Tamil plight"". Indian Express. January 29,2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [http://www.lankanewspapers.com/news/2009/2/39361_space.html MURUGATHASAN IMMOLATED INFRONT OF THE UN IN GENEVA IN PROTEST OF TAMIL SUFFERINGS ]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [ http://news.webindia123.com/news/Articles/India/20090225/1185659.html ]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ [7]

- ^ [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ [10]

- ^ [11]