Healthcare reform debate in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States |

|---|

|

|

| Healthcare in the United States |

|---|

The health care reform debate in the United States has for several decades centered around the questions of whether fundamental reform of the system is needed, what form those reforms should take, and how they should be funded. Issues regarding publicly funded health care are frequently the subject of political debate.[1] Whether or not a publicly funded universal health care system should be implemented is one such example.[2]

The health care reform debate in the United States has been influenced by the teabagger phenomenon, with reporters and politicians spending time reacting to it.[3][4] Supporters of a greater government role in healthcare, such as former insurance PR executive Wendell Potter, argue that the hyperbole generated by this phenomenon is a form of corporate astroturfing which he used to write for CIGNA.[5] Opponents of more government involvement, such as Phil Kerpen whose funding comes mainly from Koch Industries, counter-argue that those corporations oppose a public-plan, but some try to push for government actions that will unfairly benefit them, like employer mandates forcing private companies to buy health insurance.[6]

The case for publicly-funded health care

Democrats are far more supportive of publicly funded health care than are Republicans[7] and argue that it has several advantages over the for-profit, free market system. It has been suggested that the largest obstacle is a lack of political will.[8]

One of the leading organizations in support of single payer in the US is Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), which seeks to establish "a system in which a single public or quasi-public agency organizes health financing, but delivery of care remains largely private."[9]. Different versions, implementations, and variations of such systems exist in every industrialized high income country other than the United States[10][11] including Canada, western Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, as well as some countries classified as "newly developed" or "in transition,"such as in Taiwan.

Converting to a single-payer system is seen by proponents as a solution to the flaws in the current system. The US health care system is the most expensive in the world.[12] Despite this expenditure, the current US system fails to provide universal coverage. Almost 46 million of the American population, more than 15 percent of the total, lacked health insurance in 2007,[13] including 9.7 million who are not American citizens.[14] The lack of universal coverage contributes to another flaw in the current US health care system: on most dimensions of performance, it underperforms relative to other industrialized countries.[15] In a 2007 comparison by the Commonwealth Fund of health care in the U.S. with that of Germany, Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, the US ranked last on measures of quality, access, efficiency, equity, and outcomes.[15]

For example, the US ranks 22nd in infant mortality, between Taiwan and Croatia,[16] 46th in life expectancy, between Saint Helena and Cyprus,[17] and 37th in health system performance, between Costa Rica and Slovenia.[18]

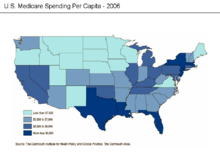

The US system is often compared with that of its northern neighbor, Canada (see Canadian and American health care systems compared). Canada's system is largely publicly funded. In 2006, Americans spent an estimated US$6,714 per capita on health care, while Canadians spent US$3,678.[19] This amounted to 15.3% of US GDP in that year, while Canada spent 10.0% of GDP on health care.

A 2007 review of all studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the US found that "health outcomes may be superior in patients cared for in Canada versus the United States, but differences are not consistent."[20]

Proponents of health care reform argue that moving to a single-payer system would reallocate the money currently spent on the administrative overhead required to run the hundreds[21] of insurance companies in the US to provide universal care.[22] An often-cited study by Harvard Medical School and the Canadian Institute for Health Information determined that some 31 percent of US health care dollars, or more than $1,000 per person per year, went to health care administrative costs.[23]

Advocates argue that shifting the US to a single-payer health care system would provide universal coverage, give patients free choice of providers and hospitals, and guarantee comprehensive coverage and equal access for all medically necessary procedures, without increasing overall spending. Shifting to a single-payer system would also eliminate oversight by managed care reviewers, restoring the traditional doctor-patient relationship.[24]

Quality of care

One political advocacy group has claimed that a free market solution to health care provides a lower quality of care, with higher mortality rates, than publicly funded systems.[25] The quality of health maintenance organizations and managed care have also been criticized by this same political advocacy group.[26]

According to a 2000 study of the World Health Organization, publicly funded systems of industrial nations spend less on health care, both as a percentage of their GDP and per capita, and enjoy superior population-based health care outcomes.[27] However, commentators have criticized the WHO's comparison method for being biased; the WHO study marked down countries for having private or fee-paying health treatment and rated countries by comparison to their expected health care performance, rather than objectively comparing quality of care.[28][29]

While most Americans are generally satisfied with the quality of their own health care,[30] some medical researchers say that patient satisfaction surveys are a poor way to evaluate medical care. Researchers at the RAND Corporation and the Department of Veterans Affairs asked 236 elderly patients in two different managed care plans to rate their care, then examined care in medical records, as reported in Annals of Internal Medicine. There was no correlation. "Patient ratings of health care are easy to obtain and report, but do not accurately measure the technical quality of medical care," said John T. Chang, UCLA, lead author.[31][32][33]

Cost and efficiency

Proponents of publicly funded health care point out that the United States spends a lower proportion of its GDP on health care (16.0%) than any other country in the world, except for East Timor (Timor-Leste).[34] The number of employers who offer health insurance is declining. Costs for employer-paid health insurance are rising rapidly: since 2001, premiums for family coverage have increased 78%, while wages have risen 19% and prices have risen 17%, according to a 2007 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation.[35] Private insurance in the US varies greatly in its coverage; one study by the Commonwealth Fund published in Health Affairs estimated that 16 million U.S. adults were underinsured in 2003. The underinsured were significantly more likely than those with adequate insurance to forgo health care, report financial stress because of medical bills, and experience coverage gaps for such items as prescription drugs. The study found that underinsurance disproportionately affects those with lower incomes — 73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.[36] One indicator of the consequences of Americans' inconsistent health care coverage is a study in Health Affairs that concluded that half of personal bankruptcies involved medical bills,[37] although other sources dispute this.[38]

Proponents of health care reforms involving expansion of government involvement to achieve universal health care argue that the need to provide profits to investors in a predominantly free market health system, and the additional administrative spending, tends to drive up costs, leading to more expensive health care provision.[25]

The case against publicly-funded health care

Those who oppose publicly funded health care argue that there are flaws in publicly funded health care systems, such as those which operate in Canada, the United Kingdom and Germany. They argue that these systems have poor quality of care, long waiting lists, and slow access to new drugs.[28][39][40][41] Potential increased wait times have ironically led many to contend that a move to a single payer system would accelerate the current growth trends of Americans leaving the US for care through medical tourism [42]

Supporters of the for-profit, free market health care system contend that the high level of administrative costs cited by advocates of publicly funded care arise out of the substantial level of government regulation that exists in the United States health care sector.[43] According to a study by the Cato Institute this regulation provides benefits in the amount of $170 billion but costs the public up to $340 billion.[43]

While polling data indicate that US citizens are concerned about health care costs and there is substantial support for some type of reform, most are generally satisfied with the quality of their own health care. According to a Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health in 2003, 86.9% of Americans reported being "satisfied" or "very satisfied" with their health care services, compared to 83.2% of Canadians.[30] In the same study, 93.6% of Americans reported being "satisfied" or "very satisfied" with their physician services, compared to 91.5% of Canadians (according to the study authors, that difference was not statistically significant).

For this reason, some U.S. reformers argue for other, more incremental changes to achieve universal health care, such as tax credits or vouchers.[44] However, proponents of a single-payer system, such as Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, assert that incremental changes in a free-market system are "doomed to fail."[45]

Quality of care

International comparisons of health care quality have yielded mixed results. For example, an international comparison of health systems in six countries by the Commonwealth Fund ranked the UK's publicly funded system first overall and first in quality of care. Systems in the United States and Canada tied for the lowest overall ranking and toward the bottom for quality of care.[46]

Overall, Canadians are quite satisfied with the quality of health care they receive. In a regularly conducted opinion poll, 70% of Canadians reported that they were either very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the quality of care they receive compared to 30% being somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. The main factor of dissatisfaction is waiting times.[47]

In survey data, Canadian and British respondents were three to four times more likely to wait more than 6 months for elective surgery than those in the U.S. However, marginally more people in the U.S. reported wait times over six months than those in the Netherlands and in Germany. U.S. respondents were four to five times more likely than their Canadian counterparts to skip a medical test or treatment recommended by a doctor and twice as likely as their Canadian counterparts to have spent more than US$1000 on medical costs in the previous year and seven times more likely to skip treatment or have spent more than US$1000 as their British counterparts [48].

Public health care varies significantly from country to country. Many countries allow for private medicine in addition to the public health care system. Some countries, e.g. Norway, have more doctors per capita than the United States.[49] Also, the US does not have any official record for waiting lists, but a 2005 survey by the Commonwealth Fund of sick adults in six nations found that only 47% of US patients could get a same- or next-day appointment for a medical problem, worse than every other country except Canada. [50]

Innovation and development of new treatments

Free market advocates say that the largely free market system of health care in the United States has led to the faster development of more advanced medical treatment and new drugs, and that cancer patients in the United States for many forms of cancer, including those of the breast, thyroid and lung, have higher survival rates than their counterparts in publicly-funded health systems in Europe.[40] Some analysts have pointed out the difficulty of comparing international health statistics. In particular, the mortality rates for cancer in the United States is at about the same level as many other countries, suggesting that the higher survival rates are a function of the way cancer is diagnosed.[51] Market advocates say that public care systems, in which there is more bureaucratic government involvement and less financial incentive in the health care industry, lead to less motivation for medical innovation and invention.[52]

By some criteria, the United States, with its partly free-market health care system, is the world leader in medical innovation.[53] According to economist Tyler Cowen quoted in The New York Times, the American system leads in converting new ideas into workable commercial technologies, and the research environment in the United States, compared with Europe, is richer, more competitive, more meritocratic and less tolerant of waste. Cohen argues that the American government could use its size to bargain down health care prices, but in the longer run it would cost lives because of the reduced innovation. Cohen argues that one reason America's leadership in innovation does not translate into higher life expectancy is that other wealthy countries also benefit from US medical innovations. Economist Arnold Kling says that America's role in medical innovation is crucial not just for Americans, but for the entire world.[54] In June 2008 the Financial Times reported that leading pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, Roche and Merck-Serono, were reducing the amount of clinical research they performed in the United Kingdom. The companies say that the policies of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) result in too few UK patients receiving "gold standard" care to provide the comparison group needed for clinical trials. [55]

Common arguments for and against a national health care system

Template:MultiCol From supporters:

- In most cases, people have little influence on whether or not they will contract an illness. Consequently, illness may be viewed as a fundamental part of what it means to be human and, as such, access to treatment for illness should be based on acknowledgement of the human condition, not the ability to pay[56][57][58][59] or entitlement.[60] Therefore, health care may be viewed as a fundamental human right itself or as an extension of the right to life. [61]

- Since people perceive universal health care as free, they are more likely to seek preventative care which, in the long run, lowers their overall health care expenditure by focusing treatment on small, less expensive problems before they become large and costly.[62]

- A universal health care system allows for a larger capital base than can be offered by free market insurers (without violating antitrust laws). A larger capital base "spreads out" the cost of a payout among more people, lowering the cost to the individual.

- Universal health care would provide for uninsured adults who may forgo treatment needed for chronic health conditions.[63]

- In most free-market situations, the consumer of health care is entirely in the hands of a third party who has a direct personal interest in persuading the consumer to spend money on health care in his or her practice. The consumer is not able to make value judgments about the services judged to be necessary because he or she may not have sufficient expertise to do so.[64] This, it is claimed, leads to a tendency to over produce. In socialized medicine, hospitals are not run for profit and doctors work directly for the community and are assured of their salary. They have no direct financial interest in whether the patient is treated or not, so there is no incentive to over provide. When insurance interests are involved this furthers the disconnect between consumption and utility and the ability to make value judgments. [65] Others argue that the reason for over production is less cynically driven but that the end result is much the same.[66].

- The profit motive in medicine values money above public benefit.[67] For example, pharmaceutical companies have reduced or dropped their research into developing new antibiotics, even as antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are increasing, because there's less profit to be gained there than in other drug research.[68] Those in favor of universal health care posit that removing profit as a motive will increase the rate of medical innovation.[69]

- Paul Krugman and Robin Wells say that in response to new medical technology, the American health care system spends more on state-of-the-art treatment for people who have good insurance, and spending is reduced on those lacking it.[70]

- The profit motive adversely affects the cost and quality of health care. If managed care programs and their concomitant provider networks are abolished, then doctors would no longer be guaranteed patients solely on the basis of their membership in a provider group and regardless of the quality of care they provide. Theoretically, quality of care would increase as true competition for patients is restored.[71]

- Wastefulness and inefficiency in the delivery of health care would be reduced.[72] A single payer system could save $286 billion a year in overhead and paperwork.[73] Administrative costs in the U.S. health care system are substantially higher than those in other countries and than in the public sector in the US: one estimate put the total administrative costs at 24 percent of U.S. health care spending.[74] It might only take one government agent to do the job of two health insurance agents.[75] According to one estimate roughly 50% of health care dollars are spent on health care, the rest go to various middlemen and intermediaries. A streamlined, non-profit, universal system would increase the efficiency with which money is spent on health care.[76]

- About 60% of the U.S. health care system is already publicly financed with federal and state taxes, property taxes, and tax subsidies - a universal health care system would merely replace private/employer spending with taxes. Total spending would go down for individuals and employers.[77]

- Several studies have shown a majority of taxpayers and citizens across the political divide would prefer a universal health care system over the current U.S. system[78][79][80]

- America spends a far higher percentage of GDP on health care than any other country but has worse ratings on such criteria as quality of care, efficiency of care, access to care, safe care, equity, and wait times, according to the Commonwealth Fund.[46]

- A universal system would align incentives for investment in long term health-care productivity, preventive care, and better management of chronic conditions.[62]

- The Big Three of U.S. car manufacturers have cited health-care provision as a financial disadvantage. The cost of health insurance to U.S. car manufacturers adds between USD 900 and USD 1,400 to each car made in the U.S.A.[81]

- In countries in Western Europe with public universal health care, private health care is also available, and one may choose to use it if desired. Most of the advantages of private health care continue to be present, see also Two-tier health care.[82]

- Universal health care and public doctors would protect the right to privacy between insurance companies and patients.[83]

- Public health care system can be used as independent third party in disputes between employer and employee.[84]

- A study of hospitals in Canada found that death rates are lower in private not-for-profit hospitals than in private for-profit hospitals.[85]

| class="col-break " |

From opponents:

- Health care is not a right. [86][87] Thus, it is not the responsibility of government to provide health care.[88]

- Free health care can lead to overuse of medical services, and hence raise overall cost.[89][90]

- Universal health coverage does not in practice guarantee universal access to care. Many countries offer universal coverage but have long wait times or ration care.[91]

- The federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act requires hospitals and ambulance services to provide emergency care to anyone regardless of citizenship, legal status or ability to pay.[92][93][94][95]

- Eliminating the profit motive will decrease the rate of medical innovation.[96]

- It slows down innovation and inhibits new technologies from being developed and utilized. This simply means that medical technologies are less likely to be researched and manufactured, and technologies that are available are less likely to be used.[97]

- Publicly-funded medicine leads to greater inefficiencies and inequalities. [86][96][98] Opponents of universal health care argue that government agencies are less efficient due to bureaucracy.[98] Universal health care would reduce efficiency because of more bureaucratic oversight and more paperwork, which could lead to fewer doctor-patient visits. [99] Advocates of this argument claim that the performance of administrative duties by doctors results from medical centralization and over-regulation, and may reduce charitable provision of medical services by doctors.[87]

- Converting to a single-payer system could be a radical change, creating administrative chaos.[100]

- Data on liver and heart transplants suggest that access to transplants (especially the sickest patients) and outcomes in the US are as among the best in the world.[101]

- The extra spending in the US is justified if expected life span increases by only about half a year as a result.[102]

- Unequal access and health disparities still exist in universal health care systems.[103]

- The problem of rising health care costs is occurring all over the world; this is not a unique problem created by the structure of the US system.[91]

- Universal health care suffers from the same financial problems as any other government planned economy. It requires governments to greatly increase taxes as costs rise year over year. Universal health care essentially tries to do the economically impossible.[104] Empirical evidence on the Medicare single payer-insurance program demonstrates that the cost exceeds the expectations of advocates.[105] As an open-ended entitlement, Medicare does not weigh the benefits of technologies against their costs. Paying physicians on a fee-for-service basis also leads to spending increases. As a result, it is difficult to predict or control Medicare's spending.[103] The Washington Post reported in July 2008 that Medicare had "paid as much as $92 million since 2000" for medical equipment that had been ordered in the name of doctors who were dead at the time.[106] Medicare's administrative expense advantage over private plans is less than is commonly believed.[107][108][109][110] Large market-based public program such as the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program and CalPERS can provide better coverage than Medicare while still controlling costs as well.[111][112]

- National health systems tend to be more effective as they incorporate market mechanisms and limit centralized government control.[91]

- Some commentators have opposed publicly-funded health systems on ideological grounds, arguing that public health care is a step towards socialism and involves extension of state power and reduction of individual freedom.[113]

- The right to privacy between doctors and patients could be eroded if government demands power to oversee the health of citizens.[114]

- Universal health care systems, in an effort to control costs by gaining or enforcing monopsony power, sometimes outlaw medical care paid for by private, individual funds.[115][116]

Reform strategies

Overall strategy

Mayo Clinic President and CEO Denis Cortese has advocated an overall strategy to guide reform efforts. He argued that the U.S. has an opportunity to redesign its healthcare system and that there is a wide consensus that reform is necessary. He articulated four "pillars" of such a strategy:[117]

- Focus on value, which he defined as the ratio of quality of service provided relative to cost;

- Pay for and align incentives with value;

- Cover everyone;

- Establish mechanisms for improving the healthcare service delivery system over the long-term, which is the primary means through which value would be improved.

Writing in The New Yorker, surgeon Atul Gawande further distinguished between the delivery system, which refers to how medical services are provided to patients, and the payment system, which refers to how payments for services are processed. He argued that reform of the delivery system is critical to getting costs under control, but that payment system reform (e.g., whether the government or private insurers process payments) is considerably less important yet gathers a disproportionate share of attention. Gawande argued that dramatic improvements and savings in the delivery system will take "at least a decade." He recommended changes that address the over-utilization of healthcare; the refocusing of incentives on value rather than profits; and comparative analysis of the cost of treatment across various healthcare providers to identify best practices. He argued this would be an iterative, empirical process and should be administered by a "national institute for healthcare delivery" to analyze and communicate improvement opportunities.[118]

Use of comparative effectiveness research

Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. Writing in the New York Times, David Leonhardt described how the cost of treating the most common form of early-stage, slow-growing prostate cancer ranges from an average of $2,400 (watchful waiting to see if the condition deteriorates) to as high as $100,000 (radiation beam therapy):[119]

Some doctors swear by one treatment, others by another. But no one really knows which is best. Rigorous research has been scant. Above all, no serious study has found that the high-technology treatments do better at keeping men healthy and alive. Most die of something else before prostate cancer becomes a problem.

According to economist Peter A. Diamond and research cited by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.[120]

Although the Mayo Clinic scores above the other two [in terms of quality of outcome], its cost per beneficiary for Medicare clients in the last six months of life ($26,330) is nearly half that at the UCLA Medical Center ($50,522) and significantly lower than the cost at Massachusetts General Hospital ($40,181)...The American taxpayer is financing these large differences in costs, but we have little evidence of what benefit we receive in exchange.

Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. OMB Director Peter Orszag stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."[121]

Reform of doctor's incentives

Critics have argued that the healthcare system has several incentives that drive costly behavior. Two of these include:[122]

- Doctors are typically paid for services provided rather than with a salary. This provides a financial incentive to increase the costs of treatment provided.

- Patients that are fully insured have no financial incentive to minimize the cost when choosing from among alternatives. The overall effect is to increase insurance premiums for all.

Gawande quoted one surgeon who stated: "We took a wrong turn when doctors stopped being doctors and became businessmen." Gawande identified various revenue-enhancing approaches and profit-based incentives that doctors were using in high-cost areas that may have caused the over-utilization of healthcare. He contrasted this with lower-cost areas that used salaried doctors and other techniques to reward value, referring to this as a "battle for the soul of American medicine."[123]

Tax reform

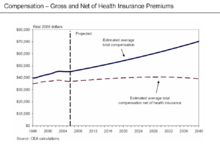

The Congressional Budget Office has also described how the tax treatment of insurance premiums may affect behavior:[124]

One factor perpetuating inefficiencies in health care is a lack of clarity regarding the cost of health insurance and who bears that cost, especially employment-based health insurance. Employers’ payments for employment-based health insurance and nearly all payments by employees for that insurance are excluded from individual income and payroll taxes. Although both theory and evidence suggest that workers ultimately finance their employment-based insurance through lower take-home pay, the cost is not evident to many workers...If transparency increases and workers see how much their income is being reduced for employers’ contributions and what those contributions are paying for, there might be a broader change in cost-consciousness that shifts demand.

Peter Singer wrote in the New York Times that the current exclusion of insurance premiums from compensation represents a $200 billion subsidy for the private insurance industry and that it would likely not exist without it.[125] In other words, taxpayers might be more inclined to change behavior or the system itself if they were paying $200 billion more in taxes each year related to health insurance. To put this amount in perspective, the federal government collected $1,146 billion in income taxes in 2008,[126] so $200 billion represents a 17.5% increase in the effective tax rate.

Independent advisory panels

President Obama has proposed an "Independent Medicare Advisory Panel" (IMAC) to make recommendations on Medicare reimbursement policy and other reforms. Comparative effectiveness research would be one of many tools used by the IMAC. The IMAC concept was endorsed in a letter from several prominent healthcare policy experts, as summarized by OMB Director Peter Orszag:[127]

Their support of the IMAC proposal underscores what most serious health analysts have recognized for some time: that moving toward a health system emphasizing quality rather than quantity will require continual effort, and that a key objective of legislation should be to put in place structures (like the IMAC) that facilitate such change over time. And ultimately, without a structure in place to help contain health care costs over the long term as the health market evolves, nothing else we do in fiscal policy will matter much, because eventually rising health care costs will overwhelm the federal budget.

Both Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. Denis Cortese and Surgeon/Author Atul Gawande have argued that such panel(s) will be critical to reform of the delivery system and improving value. Washington Post columnist David Ignatius has also recommended that President Obama engage someone like Cortese to have a more active role in driving reform efforts.[128]

Arguments regarding rationing of care

Healthcare rationing may refer to the restriction of medical care service delivery based on any number of objective or subjective criteria. Republican Newt Gingrich argued that the reform plans supported by President Obama expand the control of government over healthcare decisions, which he referred to as a type of healthcare rationing.[129] However, President Obama has argued that U.S. healthcare is already rationed, based on income, type of employment, and pre-existing medical conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured. He argued that millions of Americans are denied coverage or face higher premiums as a result of pre-existing medical conditions.[130]

Peter Singer wrote in the New York Times in July 2009 that healthcare is rationed in the United States and argued for improved rationing processes:[131]

Health care is a scarce resource, and all scarce resources are rationed in one way or another. In the United States, most health care is privately financed, and so most rationing is by price: you get what you, or your employer, can afford to insure you for...Rationing health care means getting value for the billions we are spending by setting limits on which treatments should be paid for from the public purse. If we ration we won’t be writing blank checks to pharmaceutical companies for their patented drugs, nor paying for whatever procedures doctors choose to recommend. When public funds subsidize health care or provide it directly, it is crazy not to try to get value for money. The debate over health care reform in the United States should start from the premise that some form of health care rationing is both inescapable and desirable. Then we can ask, What is the best way to do it?"

David Leonhardt also wrote in the New York Times in June 2009 that rationing is a part of economic reality: "The choice isn’t between rationing and not rationing. It’s between rationing well and rationing badly. Given that the United States devotes far more of its economy to health care than other rich countries, and gets worse results by many measures, it’s hard to argue that we are now rationing very rationally."[132]

During 2009, former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin wrote against rationing by government entities, referring to what she interpreted as such an entity in current reform legislation as a "death panel" and "downright evil." Defenders of the plan indicated that the proposed legislation H.R. 3200 would allow Medicare for the first time to cover patient-doctor consultations about end-of-life planning, including discussions about drawing up a living will or planning hospice treatment. Patients could seek out such advice on their own, but would not be required to. The provision would limit Medicare coverage to one consultation every five years.[133] However, Palin also had supported such end of life counseling and advance directives from patients during 2008.[134]

Others, such as former Republican Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson, have indicated that some form of rationing is inevitable and desirable considering the state of U.S. finances and the trillions of dollars of unfunded Medicare liabilities. He estimated that 25-33% of healthcare services are provided to those in the last months or year of life and advocated restrictions in cases where quality of life cannot be improved. He also recommended that a budget be established for government healthcare expenses, through establishing spending caps and pay-as-you-go rules that require tax increases for any incremental spending. He has indicated that a combination of tax increases and spending cuts will be required. All of these issues would be addressed under the aegis of a fiscal reform commission.[135]

Medical malpractice costs

Critics have argued that medical malpractice costs are significant and should be addressed in healthcare reform.[136] However, none of the three major bills under consideration address this issue. Medical malpractice, such as doctor errors resulting in harm to patients, has several direct and indirect costs that ultimately increase insurance premiums for patients:

- higher malpractice insurance premiums for doctors;

- additional tests or procedures to avoid potential lawsuits, called "defensive medicine";

- direct costs of jury awards, which affect malpractice premiums;

- doctors leaving the profession or specialty area, creating lesser supply and therefore higher costs, due to prohibitively expensive insurance; and

- reduced worker productivity as a result of injury.

How much these costs are is a matter of debate. Some have argued that malpractice lawsuits are a major driver of medical costs.[137] However, the direct cost of malpractice suits amounts to only about 0.5% of all healthcare spending, and a 2006 Harvard study showed that over 90% of the malpractice suits examined contained evidence of injury to the patient and that frivolous suits were generally readily dismissed by the courts.[138]

Other studies place the direct and indirect costs of malpractice between 5% and 10% of total U.S. medical costs, as described below:[139]

"About 10 percent of the cost of medical services is linked to malpractice lawsuits and more intensive diagnostic testing due to defensive medicine, according to a January 2006 report prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP for the insurers’ group America’s Health Insurance Plans...The figures were taken from a March 2003 study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that estimated the direct cost of medical malpractice was 2 percent of the nation’s health-care spending and said defensive medical practices accounted for 5 percent to 9 percent of the overall expense."

Consequences of not controlling healthcare costs

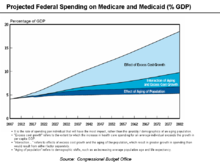

The Congressional Budget Office reported in June 2008 that:[140]

"Future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid—the federal government’s major health care programs—will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs—which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices—is ultimately the nation’s central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy...total federal Medicare and Medicaid outlays will rise from 4 percent of GDP in 2007 to 12 percent in 2050 and 19 percent in 2082—which, as a share of the economy, is roughly equivalent to the total amount that the federal government spends today. The bulk of that projected increase in health care spending reflects higher costs per beneficiary rather than an increase in the number of beneficiaries associated with an aging population."

In other words, all other federal spending categories (e.g., Social Security, Defense, Education, and Transportation) would require borrowing to be funded, which is not feasible.

President Obama stated in May 2009: "But we know that our families, our economy, and our nation itself will not succeed in the 21st century if we continue to be held down by the weight of rapidly rising health care costs and a broken health care system...Our businesses will not be able to compete; our families will not be able to save or spend; our budgets will remain unsustainable unless we get health care costs under control."[141]

See also

- Health care compared - tabular comparisons of the US, Canada, and other countries.

- Health care reform

- Health economics

- Health insurance cooperative

- Health insurance exchange

- Health policy analysis

- Health care politics

- History of health care reform in the United States

- List of healthcare reform advocacy groups in the United States

- Public opinion on health care reform in the United States

- Uninsured in the United States

- Wendell Potter

- Worldchanging's simple argument for Why We Need Government-Run, Universal, Socialized, (call it whatever you want) Health Insurance (4.5 stars on YouTube with 34K views) from Andy Lubershane at Worldchanging

References

- ^ Democracy Now! | Election Issue 2004: A Debate on Healthcare

- ^ "The Great Health Care Debate of 1993-94"

- ^ Bowser, Andre (August 22, 2009). "TEA Party protests health care reform plan". East Valley Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Copeland, Mike (August 15, 2009). "Local Tea Party members protest Obama health care plan at Chet Edwards' Waco office". Waco Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Wendell Potter. "Commentary: How insurance firms drive debate". CNN. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "The Grass Is AstroTurf-er on the Other Side". Fox News. August 12, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Poll Finds Americans Split by Political Party Over Whether Socialized Medicine Better or Worse Than Current System" (Press release). Harvard School of Public Health. 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Timid ideas won't fix health mess. By Marie Cocco, Sacramento Bee, February 10, 2007

- ^ Single-Payer National Health Insurance

- ^ [1]

- ^ [http://www.medicareforall.org/pages/List_of_Industrialized_Countries 27 free-market, high-income industrialized countries: 26 have health care for all; 1 does not: the U.S.]

- ^ "Expenditure on Health". OECD Health Division. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007." U.S. Census Bureau. Issued August 2008.

- ^ "White House Claim of 46 Million Uninsured 'Americans' Includes Almost 10 Million Foreigners". Cybercast News Service. 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ a b "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care". Report by the Commonwealth Fund. 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "Rank Order - Infant Mortality Rate". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Rank Order - Life Expectancy at Birth". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "The World Health Report 2000" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ OECD Health Data 2008: How Does Canada Compare

- ^ [2]Open Medicine, Vol 1, No 1 (2007), Research: A systematic review of studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the United States, Gordon H. Guyatt, et al.

- ^ The trade association AHIP, America's Health Insurance Plans, has some 1,300 members.

- ^ "The Health Care Crisis and What to Do About It" By Paul Krugman, Robin Wells, New York Review of Books, March 23, 2006

- ^ Costs of Health Administration in the U.S. and Canada Woolhandler, et al., NEJM 349(8) Sept. 21, 2003

- ^ Physicians for a National Health Program. "What is Single Payer?"

- ^ a b For-Profit Hospitals Cost More and Have Higher Death Rates, Physicians for a National Health Program

- ^ For-Profit HMOs Provide Worse Quality Care, Physicians for a National Health Program

- ^ Prelims i-ixx/E

- ^ a b Why Isn't Government Health Care The Answer?, Free Market Cure, 16 July 2007

- ^ Glen Whitman, "WHO’s Fooling Who? The World Health Organization’s Problematic Ranking of Health Care Systems," Cato Institute, February 28, 2008

- ^ a b Satisfaction with health care and physician services, Canada and United States, 2002 to 2003

- ^ Capital: In health care, consumer theory falls flat David Wessel, Wall Street Journal, September 7, 2006.

- ^ "Rand study finds patients' ratings of their medical care do not reflect the technical quality of their care" (Press release). RAND Corporation. 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Patients' Global Ratings of Their Health Care Are Not Associated with the Technical Quality of Their Care, John T. Chang, et al., Ann Intern Med. 2006 May 2;144(9):665-72. [PMID16670136]

- ^ WHO (2009). "World Health Statistics 2009". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Health Insurance Premiums Rise 6.1 Percent In 2007, Less Rapidly Than In Recent Years But Still Faster Than Wages And Inflation" (Press release). Kaiser Family Foundation. 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Schoen, C. (2005-06-14). "Insured But Not Protected: How Many Adults Are Underinsured?". Health Affairs Web Exclusive. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w5.289. PMID 15956055. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Illness And Injury As Contributors To Bankruptcy", by David U. Himmelstein, Elizabeth Warren, Deborah Thorne, and Steffie Woolhandler, Health Aff (Millwood). 2005 Jan-Jun;Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-63-W5-73. [PMID15689369]

- ^ Todd Zywicki, "An Economic Analysis of the Consumer Bankruptcy Crisis", 99 NWU L. Rev. 1463 (2005)

- ^ The Myths of Single-Payer Health Care, Free Market Cure, 16 July 2007

- ^ a b A Story Michael Moore Didn't Tell, Washington Post, 18 July 2007

- ^ [3], Fraser Institute, 24 July 2007

- ^ http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/us_chs_MedicalTourismStudy(1).pdf

- ^ a b Christopher J. Conover (4-10-2004). "Health Care Regulation: A $169 Billion Hidden Tax" (PDF). Cato Policy Analysis. 527: 1–32.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. Health care vouchers -- a proposal for universal coverage. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1255-1260.

- ^ "Are we in a health care crisis?". PBS companion website: The Health Care Crisis: Who's At Risk?. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care" by Karen Davis, Ph.D., Cathy Schoen, M.S., Stephen C. Schoenbaum, M.D., M.P.H., Michelle M. Doty, Ph.D., M.P.H., Alyssa L. Holmgren, M.P.A., Jennifer L. Kriss, and Katherine K. Shea Commonwealth Fund, May 15, 2007.

- ^ http://www.mediresource.com/e/pages/hcc_survey/pdf/HCiC_1998-2003_retro.pdf A POLLARA Report: Health Care in Canada Survey: Retrospective 1998-2003

- ^ http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/26/6/w717?ijkey=26910bb1cf98fbaeea34afeb08f3e8f18fc98a7c#SEC2

- ^ Core Health Indicators

- ^ The Doctor Will See You—In Three Months

- ^ Ezra Klein: Rudy and "Socialized Medicine"

- ^ Pipes, S. Border Crossings, Pacific Research Institute, October 17, 2003. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ^ Tyler Cowen, "Poor U.S. Scores in Health Care Don’t Measure Nobels and Innovation", The New York Times, October 5, 2006.

- ^ Kling, Arnold (June 30, 2007), "Two heath-care documentaries", The Washington Times

- ^ Andrew Jack, "Big drugs companies shift trials from UK," The Financial Times, June 26, 2008

- ^ Center for Economic and Social Rights. "The Right to Health in the United States of America: What Does it Mean?" October 29, 2004.

- ^ The Right to Health in the United States of America: What Does it Mean?, Center for Economic and Social Rights, October 2004

- ^ Human Rights, Homelessness and Health Care, National Health Care for the Homeless Council

- ^ National Health Care for the Homeless Council. "Human Rights, Homelessness and Health Care".

- ^ Kereiakes DJ, Willerson JT. "US health care: entitlement or privilege?." Circulation. 2004 March 30;109(12):1460-2.

- ^ United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948. Article 25 states: "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control."

- ^ a b "The Best Care Anywhere" by Phillip Longman, Washington Monthly, January 2005.

- ^ http://covertheuninsured.org/media/docs/release050205a.pdf

- ^ Blomqvist, Åke; Léger, Pierre Thomas (2005)“Information asymmetry, insurance and the decision to hospitalize,” Journal of Health Economics, Vol 24(4), pp. 775-793.

- ^ British National Party - Chairman Nick Griffin - Working to secure a future for British children

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=15233303 NPR discussion with author Shannon Brownlee who argues that the system overly rewards doing stuff

- ^ Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Angell M, Young QD (2003). "Proposal of the Physicians' Working Group for Single-Payer National Health Insurance". JAMA. 290 (6): 798–805. doi:10.1001/jama.290.6.798. PMID 12915433. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Russell, Sabin (2008-01-20). "Bacteria race ahead of drugs". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ For example, the recent discovery that dichloroacetate (DCA) can causes regression in several cancers, including lung, breast and brain tumors.Alberta scientists test chemotherapy alternative Last Updated: Wednesday, January 17, 2007 The DCA compound is not patented or owned by any pharmaceutical company, and, therefore, would likely be an inexpensive drug to administer, Michelakis added. The bad news, is that while DCA is not patented, Michelakis is concerned that it may be difficult to find funding from private investors to test DCA in clinical trials.University of Alberta - Small molecule offers big hope against cancer. January 16, 2007

- ^ Paul Krugman, Robin Wells, "The Health Care Crisis and What to Do About It"

- ^ Pajamas Media

- ^ Paul Krugman and Robin Wells, The Health Care Crisis and What to Do About It, New York Review of Books, 2006-03-23, accessed 2007-10-28

- ^ Public Citizen. "Study Shows National Health Insurance Could Save $286 Billion on Health Care Paperwork:" http://www.citizen.org.

- ^ http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/3/10 Reinhardt, Hussey and Anderson, "U.S. Health Care Spending In An International Context", Health Affairs, 23, no. 3 (2004): 10-25

- ^ William F. May. "The Ethical Foundations of Health Care Reform," The Christian Century, June 1-8, 1994, pp. 572-576.

- ^ Statement of Dr. Marcia Angell introducing the U.S. National Health Insurance Act, Physicians for a National Health Program, February 4, 2003. Accessed March 4, 2008

- ^ "Won’t this raise my taxes?" PHNP.org.

- ^ Teixeira , Ruy. "Healthcare for All?" MotherJones September 27, 2005 .

- ^ CBSNews. "Poll: The Politics Of Health Care" CBSNews March 1, 2007 .

- ^ Blake, Aaron. "Poll shows many Republicans favor universal health care, gays in military" TheHill.com June 28, 2007.

- ^ "Detroit's big three seek White House help" Guardian Unlimited, November 15, 2006

- ^

""Uguali e diversi" davanti alla salute" (PDF) (in Template:It). Retrieved 2008-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^

"Il segreto professionale nella relazione medico-paziente" (PDF) (in Template:It). Retrieved 2008-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^

"LEGGE 20 maggio 1970, n. 300 (Statuto dei lavoratori)" (in Template:It). pp. ART. 5. and ART. 6. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, Lacchetti C, Weaver B, Schunemann HJ, Haines T, Lavis JN, Grant BJ, Haslam DR, Bhandari M, Sullivan T, Cook DJ, Walter SD, Meade M, Khan H, Bhatnagar N, Guyatt GH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. CMAJ. 2002 May 28;166(11):1399-406. PMID 12054406. Free Full Text.

- ^ a b Sade RM. "Medical care as a right: a refutation." N Engl J Med. 1971 December 2;285(23):1288-92. PMID 5113728. (Reprinted as "The Political Fallacy that Medical Care is a Right.")

- ^ a b David E. Kelley, A Life of One's Own:Individual Rights and the Welfare State, Cato Institute, October 1998, ISBN 1-882577-70-1

- ^ Michael Tanner, "Individual Mandates for Health Insurance: Slippery Slope to National Health Care," Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 565, April 5, 2006

- ^ Heritage Foundation News Release, "British, Canadian Experience Shows Folly of Socialized Medicine, Analyst Says," Sept. 29, 2000

- ^ The Cure: How Capitalism Can Save American Health Care [4]

- ^ a b c Michael Tanner, "The Grass Is Not Always Greener A Look at National Health Care Systems Around the World," Cato Institute, March 18, 2008

- ^ Text of act

- ^ EMTALA faq

- ^ American College of Emergency Physicians Fact Sheet: EMTALA accessed 10-23-2008

- ^ CMS EMTALA overview

- ^ a b Friedmen, David. The Machinery of Freedom. Arlington House Publishers: New York, 1978. p 65-69.

- ^ Miller, Roger Leroy, Daniel K. Benjamin, and Douglass Cecil North. The Economics of Public Issues. 13th Ed.th ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2003.

- ^ a b Goodman, John. "Five Myths of Socialized Medicine." Cato Institute: Cato's Letter. Winter, 2005.

- ^ Cato Handbook on Policy, "Chapter 7: Health Care," Cato Institute 6th Edition (2005)

- ^ Haase, Leif Wellington (2006-03-09). "Universal Coverage: Many Roads to Rome?". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ Scott Gottlieb, "Edwards and Organ Transplants," The Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2008; Page A11

- ^ Arnold Kling, "Crisis of Abundance: Rethinking How We Pay for Health Care (Paperback)"

- ^ a b Victor R. Fuchs and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, "Health Care Reform: Why? What? When?," Health Affairs, November/December 2005

- ^ Lawrence R. Huntoon, "Universal Health Coverage --- Call It Socialized Medicine"

- ^ Sue Blevins, Universal Health Care Won't Work -- Witness Medicare, The Cato Institute, 2003-04-11, accessed 2007-10-28

- ^ Christopher Lee, "Billings Used Dead Doctors' Names," The Washington Post, July 9, 2008

- ^ Douglas B. Sherlock, "Administrative Expenses of Health Plans", Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, 2009

- ^ Jeff Lemieux, "Perspective: Administrative Costs of Private Health Insurance Plans", America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2005

- ^ Merrill Matthews, "Medicare’s Hidden Administrative Costs: A Comparison of Medicare and the Private Sector," The Council for Affordable Health Insurance, January 10, 2006

- ^ Mark E. Litow, "Medicare versus Private Health Insurance: The Cost of Administration," Milliman, Inc., January 6, 2006

- ^ Michael J. O’Grady, "Health Insurance Spending Growth - How Does Medicare Compare?," Joint Economic Committee, June 17, 2003

- ^ Jeff Lemieux, "Medicare vs. FEHB Spending: A Rare, Reasonable Analysis," Centrists.org, June 2003

- ^ Moore "World of We", National Review, 13 July 2007

- ^ Universal Health Care Won't Work - Witness Medicare

- ^ Cato-at-liberty » Revolt Against Canadian Health Care System Continues

- ^ Kent Masterson Brown, "The Freedom to Spend Your Own Money on Medical Care A Common Casualty of Universal Coverage," Cato Institute, October 15, 2007

- ^ Denis Cortese Interview on Charlie Rose Show-July 2009

- ^ The New Yorker-The Cost Conundrum-June 2009

- ^ NYT-Leonhardt-In Health Reform, A Cancer Offers and Acid Test

- ^ Peter Diamond-Healthcare and Behavioral Economics-May 2008

- ^ The New Yorker-Gawande-The Cost Conundrum-June 2009

- ^ NYT-Leonhardt-In Health Reform, A Cancer Offers and Acid Test-July 2009

- ^ The New Yorker-The Cost Conundrum-June 2009

- ^ CBO-Testimony to Senate Finance Committee-June 2008

- ^ NYT-Singer-Why We Must Ration Healthcare-July 15, 2009

- ^ CBO Historical Tables

- ^ OMB Director Orszag-IMAC

- ^ Washington Post-Paging Dr. Reform-August 2009

- ^ LA Times-Gingrich-Healthcare Rationing-Real Scary

- ^ NYT-President Obama-Why We Need Healthcare Reform-August 15 2009

- ^ NYT-Singer-Why We Must Ration Healthcare-July 2009

- ^ NYT-Leonhardt-Healthcare Rationing Rhetoric Overlooks Reality-June 2009

- ^ CBS News-Palin Weighs In On Healthcare Reform-August 2009

- ^ Office of the Governor of Alaska-Healthcare Decisions Day

- ^ Peter G. Peterson on Charlie Rose-July 3 2009-About 17 min in

- ^ RCP-Roth-The High Cost of Medical Malpractice-August 2009

- ^ Philip K. Howard (Friday, July 31, 2009). "Health Reform's Taboo Topic".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Medical Malpractice Myth".

- ^ Bloomberg-Malpractice Lawsuits are Red Herring in Obama Plan

- ^ CBO Testimony

- ^ President Obama-Weekly Radio Address - May 16 2009