User:Teggles/sandbox2

Origins: late 18th century to early 20th century

The use of electricity to manipulate sound begins with modified acoustic keyboards such as the 1753 Denis d'or and the 1761 Clavecin electrique.[1] However, electricity only began to be used for generating sound with Elisha Gray’s accidental discovery of an electromechanical oscillator, which he used to create a basic electromechanical keyboard called "The Musical Telegraph" in 1876.[2] Electricity also began to be used in reproduction of recordings with Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville's 1857 phonautograph records and Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph player.[3][4]

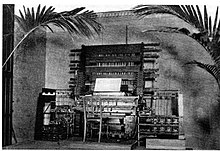

In the late 19th century, further developments were made in the use of electricity. Magnetic wire recorders were invented in the 1890s, while the phonograph and the radio began to gain popularity. The Telharmonium, an electromechnical instrument and the first to use additive synthesis, was developed and publicized by Thaddeus Cahill in the years 1897 to 1912. However, these devices predate the invention of the vacuum tube in 1906, which was almost solely responsible for the electronics revolution of the first half of the 20th century.

The invention of the first vacuum tube by Lee De Forest in 1906 led to the generation and amplification of electrical signals, radio broadcasting, and electronic computation, among other things. Forest used the vacuum tube technology to create the Audion Piano in 1915, while in 1917 Edwin Armstrong and Forest separately invented an electronic oscillator using the audio tube.

A conception of a new music involving electric instruments was proposed by Ferruccio Busoni in 1907. Busoni had read of the Telharmonium, and predicted music necessitating the use of machines and industry.[5][6] The Futurist movement, formed in 1909 by students of Busoni, promoted the use of noise in music and introduced experimental sounds inspired by machines. Futurist Luigi Russolo published his 1913 manifesto “The Art of Noises” and performed in 1914 with “acoustic noise-instruments”.[7][8]

Pioneers: 1920s - 1930s

Growing use of electronic instruments

Leon Theremin developed the theremin, an electronic instrument operated by moving one’s hands in the air, in 1920. He performed a popular tour across Europe, and in 1928 production rights were granted to RCA Victor.

Though not a commercial success, the theremin’s sound and function appealed to listeners. Records featuring it were released from 1929, and thereminist Clara Rockmore performed worldwide in 1932. The theremin was used in Joseph Schillinger’s First Airphonic Suite from 1929, Dmitri Shostakovich’s score to the the 1931 film Odna, the 1934 film Liliom, and the 1936 radio play The Green Hornet.

The Ondes Martenot was invented and first performed in 1928. Like the theremin, it was also used in popular and classical music -- the Ondes Martenot appears in the 1932 film The Idea, the 1936 Sacha Guitry's film by Adolphe Borchard and the 1937 Olivier Messiaen composition Fête des belles eaux.

George Anthiel and Fernand Léger premiered the Futurist-inspired Ballet Mécanique in 1926, which was a mechnical play featuring airplane propellers and electric bells.

Other instruments developed include the Dynaphone in 1928, the Trautonium in 1930, the Rhythmicon in 1931, the Hammond Electric Organ in 1934, the polyphonic Warbo Formant Organ in 1937, and the Melodium in 1938. [were these popular or used at all?]

Turntable music

An early precedent for the use of turntables to create music was at a Dada event in 1920, where Stephan Wolpe played eight gramophones simultaneously at widely different speeds. Darius Milhaud experimented with record manipulation in 1922, as did Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy in 1923 and Edgard Verse in 1936 -- but none ended up using them in a final work.

Paul Hindemith and Ernst Toch composed three recorded studies titled Grammophonmusik between 1929 and 1930.

1939 John Cage published Imaginary Landscape, No. 1, using two variable-speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano, and cymbal, but no electronic means of production.

Graphical sound

Optical sound, a means of storing sound recordings on transparent film, was developed and popularized in the 1920s. In 1929, Arseny Avraamov and Evgeny Sholpo realized the technology could be used to create music, and they experimented with drawing directly onto optical film to synthesize sounds.

[they predicted a future of electronic music] Several methods of the graphical sound technique were developed, such as the 1932 Variophone. From 1930-34 more than 2000 meters of soundtrack and experimental films were produced by the Multzvuk group, only some of which survive.

Experiments with sound art were also conducted, with early practitioners including Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and others. The use of graphical sound continued with works by animators and composers such as Norman McLaren.

Further conceptions of electronic music

In 1933, Edgard Varese attempted to secure funding for an electronic music studio. After failing to do so, he published his 1936 manifesto The Liberation of Sound, which … John Cage also discussed the future of electronic music in 1937, as did Percy Grainger in 1938.

- ^ Collins, Schedel, Scott Wilson 2013 p26

- ^ "Elisha Gray and "The Musical Telegraph"(1876)", 120 Years of Electronic Music, 2005, archived from the original on 2009-02-22, retrieved 2011-08-01

- ^ Rosen 2008

- ^ Publication Images

- ^ Busoni 1962, pp. 76–77

- ^ Russcol 1972, pp. 35–36

- ^ Quoted in Russcol 1972, p. 40.

- ^ Russcol 1972, p. 68.