Methane

The simplest hydrocarbon, methane, is a gas (at standard temperature and pressure, STP) with a chemical formula of CH4. Pure methane is odorless, but when used commercially is usually mixed with small quantities of odorants, strongly-smelling sulfur compounds such as ethanethiol (also called ethyl mercaptan), to enable the detection of leaks.

The principal component of natural gas, methane is a significant and plentiful fuel. Burning one molecule of methane in the presence of oxygen releases one molecule of CO2 (carbon dioxide) and two molecules of H2O (water):

- CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O

Methane's relative abundance and clean burning process makes it a very attractive fuel. However, because it is a gas and not a liquid or solid, methane is difficult to transport from the areas that produce it to the areas that consume it. Converting methane to forms that are more easily transported, such as LNG (Liquified Natural Gas) and methanol, is an active area of research.

Methane is a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential over 100 years of 23.[1] When averaged over 100 years each kg of CH4 warms the earth 23 times as much as the same mass of CO2.

The Earth's crust contains huge amounts of methane. Large amounts of methane are emitted to the atmosphere through mud volcanoes which are connected with deep geological faults or as the main constituent of biogas formed naturally by anaerobic digestion.

Properties

At room temperature and standard pressure, methane is a colorless, odorless gas. It has a boiling point of −162 °C at 1 atmosphere pressure and is extremely flammable.

Potential health effects

Methane is not toxic. The immediate health hazard is that it may cause burns if it ignites. It is highly flammable and may form explosive mixtures with air. Methane is violently reactive with oxidizers, halogens, and some halogen-containing compounds. Methane is also an asphyxiant and may displace oxygen in an enclosed space. Asphyxia may result if the oxygen concentration is reduced to below 18% by displacement. The concentrations at which flammable or explosive mixtures form are much lower than the concentration at which asphyxiation risk is significant. When structures are built on or near landfills, methane off-gas can penetrate the buildings' interiors and expose occupants to significant levels of methane. Some buildings have specially engineered recovery systems below their basements, to actively capture such fugitive off-gas and vent it away from the building. An example of this type of system is in the Dakin building, Brisbane, California.

Reactions of methane

Main reactions with methane are: combustion, hydrogen activation, and halogen reaction. In general, methane reactions are hard to control; partial oxidation to methanol, for example, is difficult to achieve; the reaction typically progresses all the way to carbon dioxide and water.

Combustion

In the combustion of methane, several steps are involved:

Methane is believed to form a methyl radical (CH3·) on heating which reacts with oxygen forming formaldehyde (HCHO or H2CO). The formaldehyde gives a formyl radical (HCO), which then forms carbon monoxide (CO). The process is called oxidative pyrolysis:

- CH4 + O2 → CO + H2 + H2O

Following oxidative pyrolysis, the H2 oxidizes, forming H2O, replenishing the active species, and releasing heat. This occurs very quickly, usually in significantly less than a millisecond.

- H2 + ½O2 → H2O

Finally, the CO oxidizes, forming CO2 and releasing more heat. This process is generally slower than the other chemical steps, and typically requires a few to several milliseconds to occur.

- CO + ½O2 → CO2

Hydrogen activation

The strength of the carbon-hydrogen covalent bond in methane is among the strongest in all hydrocarbons, and thus its use as a chemical feedstock is limited. Despite the high activation barrier for breaking the C-H bond, CH4 is still the principal starting material for manufacture of hydrogen. The search for catalysts which can facilitate C-H bond activation in methane and other low alkanes is an area of research with considerable industrial significance.

Reactions with halogens

Methane undergoes reactions with all the halogens given appropriate conditions. The reactions occur as follows:

- CH4 + X2 → CH3X + HX

Where X is a halogen: fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br) or sometimes iodine (I).

This mechanism for this process is called free radical substitution and it occurs as follows:

Initiation:

- X2 → 2X·

Propagation:

- CH4 + X· → ·CH3 + HX

- ·CH3 + X2 → CH3X + X·

Termination:

- 2X· → X2

- ·CH3 + X· → CH3X

- ·CH3 + ·CH3 → CH3CH3

This reaction can occur as far as CX4 where the halide ions will have completely displaced the hydrogens.

Uses

Fuel

For more on the use of methane as a fuel, see: natural gas

Methane is important for electrical generation by burning it as a fuel in a gas turbine or steam boiler. Compared to other hydrocarbon fuels, burning methane produces less carbon dioxide for each unit of heat released. Also, methane's heat of combustion is about 902 kJ/mol, which is lower than any other hydrocarbon, but if a ratio is made with the atomic weight (16.0 g/mol) divided by the heat of combustion (902 kJ/mol) it is found that methane, being the simplest hydrocarbon, actually produces the most heat per unit mass than other complex hydrocarbons. In many cities, methane is piped into homes for domestic heating and cooking purposes. In this context it is usually known as natural gas. One standard cubic foot of methane will produce roughly 1,000 BTU (1.06 MJ = 293 W-hr) of energy.

Industrial uses

Methane is used in industrial chemical processes and may be transported as a refrigerated liquid (liquefied natural gas, or LNG). While leaks from a refrigerated liquid container are initially heavier than air due to the increased density of the cold gas, the gas at ambient temperature is lighter than air. Gas pipelines distribute large amounts of natural gas, of which methane is a significant component.

In the chemical industry, methane is the feedstock of choice for the production of hydrogen, methanol, acetic acid, and acetic anhydride. When used to produce any of these chemicals, methane is first converted to synthesis gas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, by steam reforming. In this process, methane and steam react on a nickel catalyst at high temperatures (700–1100 °C).

- CH4 + H2O → CO + 3H2

The ratio of carbon monoxide to hydrogen in synthesis gas can then be adjusted via the water gas shift reaction to the appropriate value for the intended purpose.

- CO + H2O ⇌ CO2 + H2

Less significant methane-derived chemicals include acetylene, prepared by passing methane through an electric arc, and the chloromethanes (chloromethane, dichloromethane, chloroform, and carbon tetrachloride), produced by reacting methane with chlorine gas. However, the use of these chemicals is declining, acetylene as it is replaced by less costly substitutes, and the chloromethanes due to health and environmental concerns.

Sources of methane

Natural gas fields

The major source of methane is extraction from geological deposits known as natural gas fields. It is associated with other hydrocarbon fuels and sometimes accompanied by helium and nitrogen. The gas at shallow levels (low pressure) is formed by anaerobic decay of organic matter deep under the Earth's surface. In general, sediments buried deeper and at higher temperatures than those which give oil generate natural gas.

Alternative sources

Apart from gas fields an alternative method of obtaining methane is via biogas generated by the fermentation of organic matter including manure, wastewater sludge, municipal solid waste, or any other biodegradable feedstock, under anaerobic conditions. Industrially, methane can be created from common atmospheric gases and hydrogen (produced, perhaps, by electrolysis) through chemical reactions such as the Sabatier process, Fischer-Tropsch process. Coal bed methane extraction is a method for extracting methane from a coal deposit. It is also caused by cows' natural gas.

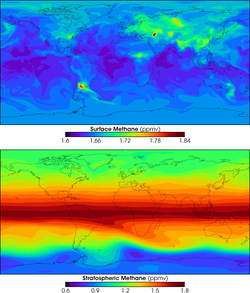

Methane in Earth's atmosphere

Methane in the earth's atmosphere is an important greenhouse gas with a Global warming potential of 23 over a 100 year period. Its concentation has increased by about 150% since 1750 and it accounts for 20% of the total radiative forcing from all of the long-lived and globally mixed greenhouse gases.[2]

The average concentration of methane at the Earth's surface in 1998 was 1,745 ppb.[3] Its concentration is higher in the northern hemisphere as most sources (both natural and human) are larger. The concentrations vary seasonally with a minimum in the late summer.

Methane is created near the surface, and it is carried into the stratosphere by rising air in the tropics. Uncontrolled build-up of methane in Earth's atmosphere is naturally checked—although human influence can upset this natural regulation—by methane's reaction with a molecule known as the hydroxyl radical, a hydrogen-oxygen molecule formed when single oxygen atoms react with water vapor.

Early in the Earth's history—about 3.5 billion years ago—there was 1,000 times as much methane in the atmosphere as there is now. The earliest methane was released into the atmosphere by volcanic activity. During this time, Earth's earliest life appeared. These first, ancient bacteria added to the methane concentration by converting hydrogen and carbon dioxide into methane and water. Oxygen did not become a major part of the atmosphere until photosynthetic organisms evolved later in Earth's history. With no oxygen, methane stayed in the atmosphere longer and at higher concentrations than it does today.

Emissions of methane

Houweling et al. (1999) give the following values for methane emissions:[3]

| Origin | CH4 emission (Teragram/yr) |

| Natural emissions | |

|---|---|

| Wetlands (incl rice production) | 225 |

| Ocean | 20 |

| Termites | 15 |

| Hydrates | 10 |

| Natural total | 290 |

| Anthropogenic emissions | |

| Energy | 110 |

| Landfills | 40 |

| Ruminants (Livestock) | 115 |

| Waste treatment | 25 |

| Biomass burning | 40 |

| Anthropogenic total | 330 |

Slightly over half of the total emission is due to human activity.[2]

Living plants (e.g. forests) have recently been identified as a potentially important source of methane. The recent paper calculated emissions of 62–236 Tg yr-1, and "this newly identified source may have important implications".[4][5] However the authors stress "our findings are preliminary with regard to the methane emission strength".[6]

See also Flatulence tax.

Removal processes

The major removal mechanism of methane from the atmosphere is by reaction with the hydroxyl radical (·OH), which may be produced when a cosmic ray strikes a molecule of water vapor:

- CH4 + ·OH → ·CH3 + H2 O

This reaction in the troposphere gives a methane lifetime of 9.6 years. Two more minor sinks are soil sinks (160 year lifetime) and stratospheric loss by reaction with ·OH, ·Cl and ·O1D in the stratosphere (120 year lifetime), giving a net lifetime of 8.4 years. [3]

Sudden release from methane clathrates

At high pressures, such as are found on the bottom of the ocean, methane forms a solid clathrate with water, known as methane hydrate. An unknown, but possibly very large quantity of methane is trapped in this form in ocean sediments. The sudden release of large volumes of methane from such sediments into the atmosphere has been suggested as a possible cause for rapid global warming events in the earth's distant past, such as the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum of 55 million years ago.

One source estimates the size of the methane hydrate deposits of the oceans at ten million million tons (10 exagrams). Theories suggest that should global warming cause them to heat up sufficiently, all of this methane could again be suddenly released into the atmosphere. Since methane is twenty-three times stronger (for a given weight, averaged over 100 years) than CO2 as a greenhouse gas; this would immensely magnify the greenhouse effect, heating Earth to unprecedented levels.

Release of methane from bogs

Although less dramatic than release from clathrates, but already happening, is an increase in the release of methane from bogs as permafrost melts. Although records of permafrost are limited, recent years (1998 and 2001) have seen record thawing of permafrost in Alaska and Siberia.

Recent measurements in Siberia show that the methane released is five times greater than previously estimated [7].

Extraterrestrial methane

Methane has been detected or is believed to exist in several locations of the solar system. It is believed to have been created by abiotic processes, with the possible exception of Mars.

Traces of methane gas are present in the thin atmosphere of the Earth's Moon.

Methane has also been detected in interstellar clouds.

- Methane is believed to be present on Charon, but it is not 100% confrimed.

See also

- Alkane, a type of hydrocarbon of which methane is simplest member.

- Anaerobic digestion

- Anaerobic respiration

- Biogas

- List of alkanes

- Methane clathrate, form of water ice which contains methane.

- Methanogen, archaea that produce methane as a metabolic by-product.

- Methanogenesis, the formation of methane by microbes.

- Methanotroph, bacteria that are able to grow using methane as their only source of carbon and energy.

- Methyl group, a functional group similar to methane.

- Organic gas

References

- ^ IPCC Third Assessment Report

- ^ a b "Technical summary". Climate Change 2001. United Nations Environment Programme.

- ^ a b c "Trace Gases: Current Observations, Trends, and Budgets". Climate Change 2001. United Nations Environment Programme.

- ^ "Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions". Nature. 2006-01-12. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ "Plants revealed as methane source". BBC. 2006-01-11. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ "Global warming - the blame is not with the plants". eurekalert.org. 2006-01-18. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Methane bubbles climate trouble". BBC. 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2006-09-07.