Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) is a bi-state port district, established in 1921 through an interstate compact, that runs most of the regional transportation infrastructure, including the bridges, tunnels, airports, and seaports, within the New York–New Jersey Port District. This 1,500 mile² (3,900 km²) District is defined as a circle with a 25-mile (40-km) radius centered on the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor.[1]

The Port Authority operates the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal, which handled the third largest amount of shipping of all ports in the United States, in 2004.[2] The Port Authority also operates Hudson River crossings, including the Holland Tunnel, Lincoln Tunnel, and George Washington Bridge connecting New Jersey with Manhattan, and a number of crossings that connect with Staten Island. The Port Authority Bus Terminal and the PATH rail system are also run by the Port Authority, as are LaGuardia, JFK, and Newark Liberty International Airport. The agency has its own 1,600-member Port Authority Police Department, which is responsible for providing safety and deterring criminal activity at Port Authority–owned-and-operated facilities.[3]

Although the Port Authority does run a good portion of the transportation structures, some bridges, tunnels, and other transportation facilities are operated independently of the Port Authority, including the Staten Island Ferry, which is operated by the New York City Department of Transportation; bridges between Manhattan and the Bronx operated by the NYCDOT; and other bridges, tunnels, operated by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority which is controlled by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA); buses, subways, and commuter rail operated by the New York City Transit Authority which is controlled by the MTA; and buses, commuter rail, and light rail operated by New Jersey Transit.

History

In the early years of the 20th century, there were disputes between the states of New Jersey and New York, over rail freights and boundaries. At the time, rail lines terminated on the New Jersey side of the harbor, while ocean shipping was centered on Manhattan and Brooklyn. Freight had to be shipped across the Hudson River in barges.[4] In 1916, New Jersey launched a lawsuit against New York over issues of rail freight, with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) issuing an order that the two states work together, subordinating their own interests to the public interest.[5] The Harbor Development Commission, a joint advisory board set-up in 1917, recommended that a bi-state authority be established to oversee efficient economic development of the port district.[6] The Port Authority of New York was established on April 30, 1921,[7] through an interstate compact between the states of New Jersey and New York. This was the first such agency in the United States, created under a provision in the Constitution of the United States permitting interstate compacts.[1] The idea for the Port Authority was conceived during the Progressive Era, which aimed to reduce political corruption and aimed for efficiency in government. With the Port Authority at a distance from political pressures, it was able to carrying longer-term infrastructure projects irrespective of the election cycles and in a more efficient manner.[8] Throughout its history, there have also been concerns about democratic accountability, or lack thereof at the Port Authority.[8]

Hudson River crossings

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were no bridge or tunnel crossings between the two states. Under an independent agency, the Holland Tunnel was constructed and opened in 1924, with the planning and construction pre-dating the Port Authority. With the rise in automobile traffic, there was demand for more Hudson River crossings. Using its ability to issue bonds and collect revenue, the Port Authority has built and managed major infrastructure projects. Early projects included bridges across the Arthur Kill, which separates Staten Island from New Jersey. The Goethals Bridge, named after chief engineer of the Panama Canal Commission General George Washington Goethals, connected Elizabeth, New Jersey and Howland Hook on Staten Island. At the south end of Arthur Kill, the Outerbridge Crossing was built and named after the Port Authority's first chairman, Eugenius H. Outerbridge. Construction of both bridges was completed in 1928. The Bayonne Bridge, opened in 1931, was built across the Kill van Kull, connecting Staten Island with Bayonne, New Jersey.[9]

Construction began in 1927 on the George Washington Bridge, linking the northern part of Manhattan with Fort Lee, New Jersey, with Port Authority chief engineer, Othmar H. Ammann, overseeing the project. The bridge was completed in October 1931, ahead of schedule and well under the estimated costs. This efficiency exhibited by the Port Authority impressed President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who used this as a model in creating the Tennessee Valley Authority and other such entities.[8]

In 1930, the Holland Tunnel was placed under control of the Port Authority, providing significant toll revenues to the Port Authority.[9] During the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Lincoln Tunnel was built, connecting New Jersey and Midtown Manhattan.

Austin J. Tobin era

Airports

In 1942, Austin J. Tobin became the Executive Director of the Port Authority. In the post-World War II period, the Port Authority expanded its operations to include airports, and marine terminals, with projects including Newark Liberty International Airport, Port Newark, and Port Elizabeth. Meanwhile, the city-owned La Guardia Field, was nearing capacity in 1939, and needed expensive upgrades and expansion. At the time, airports were operated as loss leaders, and the city was having difficulties maintaining the status quo, losing money and not able to undertake needed expansions.[10] The city was looking to hand the airports over to an public authority, possibly to Robert Moses' Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. After long negotiations with the City of New York, a 50-year lease, commencing on May 31, 1947, went to the Port Authority of New York to rehabilitate, develop, and operate La Guardia International Airport (La Guardia Field), John F. Kennedy International Airport (Idlewild Airport), and Floyd Bennett Field.[11] The Port Authority transformed the airports into fee-generating facilities, adding stores and restaurants.[10]

World Trade Center

During the post World War II period, the United States thrived economically, with increasing international trade. It was in this economic environment, that the concept of establishing a World trade center was conceived. At the time, economic growth was concentrated in Midtown Manhattan, with Lower Manhattan left out. One exception was the construction of Chase Manhattan Bank Tower in the Financial District, by David Rockefeller who led urban renewal efforts in Lower Manhattan.[9]

In initial plans made public in 1961, the World Trade Center was slated to be built on a site along the East River. Objections to the plan came from New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner, who resented that New York would be getting this $335 million project.[9] Meanwhile, New Jersey's Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M) was facing bankruptcy. Port Authority executive director, Austin J. Tobin agreed to take over control of the H&M Railroad, in exchange for support from New Jersey for the World Trade Center project. As part of this acquisition, the Port Authority would rehabilitate the Downtown and Uptown Hudson Tubes. The Port Authority would also obtain the Hudson Terminal, and decrepit buildings located above the terminal in Lower Manhattan. The Port Authority decided to demolish these buildings, and use this site along the Hudson River for the World Trade Center.

Even once the agreement between the states of New Jersey, New York, and the Port Authority was finalized, the World Trade Center plan faced continued controversy. New York City mayor Robert Wagner raised concerns about the limited extent that the Port Authority involved the city in the negotiations and deliberations. The site was the location of Radio Row electronics businesses, and the World Trade Center plans involved evicting hundreds of commercial and industrial tenants, property owners, small businesses, and approximately 100 residents, some of whom fiercely protested the forced relocation.[9]

In 1964, Minoru Yamasaki was hired by the Port Authority as architect, and came up with the idea of twin towers. To meet the Port Authority's requirement to build 10 million square feet of office space, the towers would each be 110-stories tall. The size of the project raised ire from the owner of the Empire State Building, which would lose its title of tallest building in the world.[9] Other critics objected to the idea of this much "subsidized" office space going on the open market, competing with the private sector. Others questioned the cost of the project, which in 1966 had risen to $575 million.[9] Final negotiations between The City of New York and the Port Authority centered on tax issues. A final agreement was made that the Port Authority would make annual payments in lieu of taxes, for the 40 percent of the World Trade Center leased to private tenants. The remaining space was to be occupied by state and federal government agencies. In 1962, the Port Authority had signed up the United States Customs Service as a tenant, and in 1964 they inked a deal with the State of New York to locate government offices at the World Trade Center.

In August 1968, construction on the World Trade Center's north tower started, with construction on the south tower beginning in January 1969.[12] When the World Trade Center twin towers were completed, the total costs to the Port Authority had reached $900 million.[13] The buildings were dedicated on April 4, 1973, with Tobin, who resigned the year before, absent from the ceremonies.[14]

Post-Tobin era

In 1972, William Ronan was chosen to succeed Austin Tobin as Executive Director of the Port Authority. Also in 1972, the name of the agency was changed to The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, along with structural changes implemented.[15]

In the 1990s, the Port Authority faced controversy, with Mayor Rudolph Giuliani alleging mismanagement at the Port Authority. He criticized the Port Authority for shifting airport revenues to support PATH service and other projects in New Jersey. Giuliani went as far as proposing to break up the Port Authority,[16] with New York Governor George Pataki also suggesting a break-up.[17]

September 11, 2001 attacks

The devastating terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent collapse of the World Trade Center buildings had an immense impact on the Port Authority. With Port Authority's headquarters located in 1 World Trade Center, it became deprived of a base of operations and sustained a great number of casualties. An estimated 1,400 Port Authority employees worked in the World Trade Center.[18] The Port Authority lost a total of 84 employees, including 37 Port Authority Police Officers, its Executive Director, Neil D. Levin, and police superintendent, Fred Morrone.[19] In rescue efforts following the collapse, two Port Authority police officers, John McLoughlin and Will Jimeno, were pulled out alive after spending nearly 24 hours beneath 30 feet of rubble.[20][21] Their rescue was later portrayed in the Oliver Stone film, World Trade Center.

Governance

The Port Authority is jointly headed by the governors of New York and New Jersey. Each governor, with the approval of his or her state senate, appoints six members to the Board of Commissioners, who serve overlapping six-year terms without pay.[1] A governor can veto actions by the commissioners from the same state.[1] Meetings of the Board of Commissioners are public.

Financially, the Port Authority has no power to tax and does not receive tax money from any local or state governments. Instead, it operates on the revenues it makes from its rents, tolls, fees, and facilities.

An Executive Director is appointed by the Board of Commissioners to deal with day-to-day operations and to execute the Port Authority's policies. In October 2004, Kenneth J. Ringler Jr. was appointed as Executive Director of the Port Authority,[22] after being nominated by New York Governor George Pataki.[23]

Former Executive Directors

- Eugenius H. Outerbridge

- Austin J. Tobin

- William Ronan

- Lewis M. Eisenberg

- Robert E. Boyle

- Neil D. Levin

- Frank Lautenberg

- Joseph J. Seymour[23]

Facilities

Seaports

The Port Authority operates the Brooklyn Port Authority Marine Terminal in Red Hook, Brooklyn, NY; the Auto Marine Terminal in Bayonne and Jersey City; the Howland Hook Marine Terminal on Staten Island; and the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal in Elizabeth. The Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal was the first in the nation to containerize,[24] As of 2004, Port Authority seaports handle the third largest amount of shipping of all U.S. ports, as measured in tonnage.[2]

Airports

Airports operated by the Port Authority include John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport, both of which are located in Queens, New York; Newark Liberty International Airport, located in Newark and Elizabeth, New Jersey; and Teterboro Airport, located in Teterboro, New Jersey. The Authority also operates the Downtown Manhattan Heliport. Both Kennedy and LaGuardia airports are owned by the city of New York and leased to the Port Authority for operating purposes. Newark Liberty is owned by Newark and also leased to the Authority.

Bridges and tunnels

Other facilities managed by the Port Authority include the Lincoln Tunnel, the Holland Tunnel, and the George Washington Bridge, which all connect Manhattan and northern New Jersey; the Goethals Bridge and the Outerbridge Crossing (previously the Arthur Kill Bridges and currently the Staten Island Bridges); and the Bayonne Bridge. Cash tolls for passenger vehicles crossing from New Jersey to New York City are $6; there is no toll for crossing from New York to New Jersey. Discounts are available with the E-ZPass electronic toll collection system. Annual toll receipts from these facilities typically equal the initial construction costs. The Port Authority owns all these bridges and tunnels.

Bus and rail transit

The Port Authority operates the Port Authority Bus Terminal at 42nd Street and the George Washington Bridge Bus Station, the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) rapid transit system linking lower and midtown Manhattan with New Jersey, the AirTrain Newark system linking Newark International Airport with New Jersey Transit and Amtrak via a station on the Northeast Corridor rail line, and the AirTrain JFK system linking JFK with Howard Beach (Subway) and Jamaica (Subway and Long Island Rail Road).

Real estate

The Port Authority also participates in joint development ventures around the region, including The Teleport communications center in Staten Island, Bathgate Industrial Park in The Bronx, the Essex County Resource Recovery Facility, The Legal Center in Newark, Queens West in Long Island City, NY, and The South Waterfront at Hoboken, New Jersey.

Current and future projects

Major projects by the Port Authority in the works, as of 2006, include the Freedom Tower and other construction at the World Trade Center site. Other projects include a new passenger terminal at JFK International Airport, and redevelopment of Newark Liberty International Airport's Terminal B, and rehabilitation of the Goethals Bridge.[25] The Port Authority also has plans to buy 340 new PATH rail cars.[25]

World Trade Center site

As owner of the World Trade Center site, the Port Authority has worked since 2001 on plans for reconstruction of the site, along with Silverstein Properties, and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. In 2006, the Port Authority reached a deal with Larry Silverstein, which ceded control of the Freedom Tower to the Port Authority.[26] The deal gave Silverstein rights to build three towers along the eastern side of the site, including 150 Greenwich Street, 175 Greenwich Street, and 200 Greenwich Street.[26] Also part of the plans, is the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, which will replace the temporary PATH station that opened in November 2003.

See also

- Port Authority Police Department

- Transportation in New York City

- Mass transit in New York City

- Port authority

References

- ^ a b c d "2001 Annual Report" (PDF). PANY. 2002, April 23.

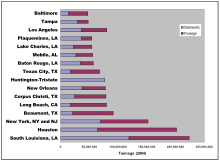

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "Tonnage for Selected U.S. Ports in 2004". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Navigation Data Center. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ "Port Authority Announces Police Promotions". PANYNJ. November 6, 2003.

- ^ Rodrigue, Jean Paul (2004). "Chapter 4, Appropriate models of port

governance Lessons from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey". Shipping and Ports in the Twenty-first Century. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|chapter=at position 38 (help) - ^ Darton, Eric (1999). "Chapter 1". Divided We Stand: A Biography of New York's World Trade Center. Basic Books.

- ^ Revell, Keith D. (2000). "Cooperation, Capture, and Autonomy: The Interstate Commerce Commission and the Port Authority in the 1920s". Journal of Policy History. 12(2): 177–214.

- ^ "History of the Port Authority". PANY. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ a b c Doig, Jameson W. (2001). "Chapter 1". Empire on the Hudson. Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). "Chapter 1". Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press.

- ^ a b Lander, Brad (August 2002). "Land Use". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "NAME OF IDLEWILD TO BE CITY AIRPORT; Cullman Proposes the Change and O'Dwyer Promises His Aid in Making Shift ADDED PRESTIGE OBJECT Port Authority Head Turns Over to Mayor the Releases From 17 Old Contracts". New York Times. May 30, 1947.

- ^ "Timeline: World Trade Center chronology". PBS - American Experience. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. (2002). "Chapter 3". Rails Under the Mighty Hudson: The Story of the Hudson Tubes, the Pennsy Tunnels, and Manhattan Transfer. Fordham University Press.

- ^ Darton, Eric (1999). "Chapter 6". Divided We Stand: A Biography of New York's World Trade Center. Basic Books.

- ^ Danielson, Michael N., Jameson W. Doig (1983). New York: The Politics of Urban Regional Development. University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Myers, Steven Lee (June 1, 1996). "Mayor Urges Breakup of Port Authority". The New York Times.

- ^ Dao, James (March 30, 1997). "Jitters for the Port Authority's Bondholders?". The New York Times.

- ^ Kifner, John and Amy Waldman (September 12, 2001). "A DAY OF TERROR: THE VICTIMS; Companies Scrambling to Find Those Who Survived, and Didn't". The New York Times.

- ^ "2002 Annual Report" (PDF). PANYNJ.

- ^ Murphy, Dean E. (September 12, 2001). "A DAY OF TERROR: THE HOPES; Survivors Are Found In the Rubble". The New York Times.

- ^ Filkins, Dexter (September 13, 2001). "AFTER THE ATTACKS: ALIVE; Entombed for a Day, Then Found". The New York Times.

- ^ "Kenneth J. Ringler, Jr". North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, Inc. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ a b "Kenneth J. Ringler Jr. elected Executive Director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Press Release)". PANYNJ. October 21, 2004.

- ^ Doig, Jameson W. (2001). "Epilogue". Empire on the Hudson. Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b "2005 Annual Report" (PDF). PANYNJ.

- ^ a b Marsico, Ron (September 22, 2006). "Deal puts Freedom Tower in P.A. control". Star-Ledger.