Puebloans

The Puebloans or Pueblo peoples are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material and religious practices. When Spaniards entered the area beginning in the 16th century, they came across complex, multi-story villages built of adobe, stone and other local materials, which they called pueblos, or towns, a term that later came to refer also to the peoples who live in these villages. There are currently 21 Pueblos that are still inhabited, among which Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are the best-known. Pueblo communities are located in the present-day states of New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas, mostly along the Rio Grande and Colorado rivers and their tributaries.

Pueblo peoples speak languages from four different language families, and each Pueblo is further divided culturally by kinship systems and agricultural practices, although all cultivate varieties of maize.

Despite increasing pressure from Spanish and later Anglo-American forces, Pueblo nations have maintained much of their traditional cultures while developing a syncretic approach to Catholicism.[1] In the 21st century, some 35,000 Pueblo Indians live in New Mexico and Arizona.

The Puebloans got a Fortnite Victory Royale

Subdivisions

Despite being a cultural and religious unit, scholars have proposed divisions of contemporary Pueblos into smaller groups.

Divisions based on linguistic affiliation

Pueblo peoples speak languages from four different language families:

- Keresan: family to which Western and Eastern Keres belong, considered by some a language isolate consisting of a dialect continuum spoken at the pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Santa Ana, Zia, Cochiti, Kewa, and San Felipe.

- Kiowa-Tanoan: stock to which the Tanoan (Puebloan) branch belongs, consisting of three separate sub-branches:

- Towa: corrently solely spoken at Jemez Pueblo.

- Tewa: the most widespread Tanoan language with several dialects, spoken at Ohkay Owingeh, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Tesuque, Nambé, and Pojoaque Pueblos.

- Tiwa: the only sub-branch composed of separate languages:[2]

- Uto-Aztecan: stock to which Hopi belongs, spoken exclusively at Hopi Pueblo.

- Zuni: family to which Zuni belongs; it is a language isolate, currently spoken exclusively at Zuni Pueblo.

Divisions based on cultural practices

Farming techniques

Anthropologists have studied Pueblo peoples extensively and published various classifications of their subdivisions. In 1950, Fred Russell Eggan contrasted the peoples of the Eastern and Western Pueblos, based largely on their subsistence farming techniques.[4] The Western or Desert Pueblos of the Zuñi and Hopi specialize in dry farming, compared to the irrigation farmers of the Eastern or River Pueblos. Both groups cultivated mostly maize (corn).

Kinship systems and Religion

In 1954, Paul Kirchhoff published a division of Pueblo peoples into two groups based on culture.[5] The Hopi, Zuni, Keres and Jemez each have matrilineal kinship systems: children are considered born into their mother's clan and must marry a spouse outside it, an exogamous practice. They maintain multiple kivas for sacred ceremonies. Their creation story tells that humans emerged from the underground. They emphasize four or six cardinal directions as part of their sacred cosmology, beginning in the north. Four and seven are numbers considered significant in their rituals and symbolism.[5]

In contrast, the Tanoan-speaking Puebloans (other than Jemez) have a patrilineal kinship system, with children considered born into their father's clan. They practice endogamy, or marriage within the clan. They have two kivas or two groups of kivas in their pueblos. Their belief system is based in dualism. Their creation story recounts the emergence of the people from underwater. They use five directions, beginning in the west. Their ritual numbers are based on multiples of three.[5]

History

The Pueblo peoples are believed to descend from an admixture of three major cultures that dominated the US Southwest region before European contact:[6]

- Mogollon Culture, who occupied an area near the Gila Wilderness.

- Hohokam Culture, the archaeological term for a settlement in the Southwest.

- Ancestral Puebloans who occupied the Mesa Verde region of the Four Corners area.[7]

The Rise of Pueblo Architecture

By about 700 to 900 AD, the Puebloans began to move away from ancient pit houses dug in cliffs and to construct connected rectangular rooms arranged in apartment-

like structures made of adobe and adapted to sites. By 1050, they had developed planned villages composed of large terraced buildings, each with many rooms. These apartment-house villages were often constructed on defensive sites: on ledges of massive rock, on flat summits, or on steep-sided mesas, locations that would afford the Anasazi protection from their Northern enemies. The largest of these villages, Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, contained around 700 rooms in five stories; it may have housed as many as 1000 persons.[8]

Pueblo buildings are constructed as complex apartments with numerous rooms, often built in strategic defensive positions. The most highly developed were large villages or pueblos situated at the very top of the mesas, the rocky tablelands typical to the Southwest.

European Contact

Before 1598, Spanish exploration of the present-day Pueblo areas was limited to an assortment of small groups. A group of colonizers led by Juan de Oñate arrived at

the end of the 16th Century as part of an apostolic mission to convert the Natives. Despite initial peaceful contact, Spain's attempts to dispose of Pueblo religion and replace it with Catholicism became increasingly more aggressive, and were met with great resistance by Puebloans, whose governmental structure was based around the figure of the cacique, a theocratical leader for both material and spiritual matters.[1] Over the years, Spaniards' methods grew harsher, leading to several revolts by the Puebloans.

Pueblo Revolt

Over a century after the successful Tiguex War led by Tiwas against the Coronado Expedition in 1540-41, which temporarily halted Spanish advances in present-day New Mexico, growing discontent among the Northern Pueblos against the abuses of the Spaniards brewed into a large organized uprising against European colonizers in 1680: the Pueblo Revolt. The Revolt was the first by a Native American group to successfully expel colonists from the area for several years.

In the 1670s, severe drought swept the region, causing a famine among the Pueblo and increasing raids by the Apache, which neither Spanish nor Pueblo soldiers were able to prevent. The unrest among the Pueblos came to a head in 1675, when Governor Juan Francisco Treviño ordered the arrest of forty-seven Pueblo medicine men and accused them of practicing sorcery. Four of the medicine men were sentenced to death by hanging; three of those sentences were carried out, while the fourth prisoner committed suicide. The remaining men were publicly whipped and sentenced to prison.

When the news of the killings and public humiliation reached Pueblo leaders, they moved in force to Santa Fe, where the prisoners were held. Because a large number of Spanish soldiers were away fighting the Apache, Governor Treviño was forced to release the prisoners. Among those released was a Ohkay Owingeh Tewa man named Popé.

After being released, Popé took up residence in Taos Pueblo far from the capital of Santa Fe and spent the next five years seeking support for a revolt among the 46 Pueblo villages. He was able to gain the support of the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley. The Pecos Pueblo, 50 miles east of the Rio Grande pledged its participation in the revolt as did the Zuni and Hopi, 120 and 200 miles respectively west of the Rio Grande. At the time, the Spanish population was of about 2,400 colonists, including mixed-blood mestizos, and Indian servants and retainers, who were scattered thinly throughout the region.

Starting early on August 10, 1680, Popé and leaders of each of the Pueblos sent a knotted rope carried by a runner to the next Pueblo; the number of knots signified the number of days to wait before beginning the uprising. Finally, on August 21st, 2,500 Puebloan warriors took the colony's capital Santa Fe from Spanish control, killing many colonizers, the remainder of whom were successfully expelled.[9]

Legacy and honors

On September 22, 2005, the statue of Po'pay (Popé), the leader of the Pueblo Revolt, was unveiled in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. The statue was the second commissioned by the state of New Mexico for National Statuary Hall; it was the 100th and last to be added to the collection, which represents the Senate. It was created by Cliff Fragua, a Puebloan from Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico. It is the only statue in the collection to be created by a Native American.[10]

Culture

In 1844 Josiah Gregg described the historic Pueblo people in The journal of a Santa Fé trader as follows:[11]

When these regions were first discovered it appears that the inhabitants lived in comfortable houses and cultivated the soil, as they have continued to do up to the present time. Indeed, they are now considered the best horticulturists in the country, furnishing most of the fruits and a large portion of the vegetable supplies that are to be found in the markets. They were until very lately the only people in New Mexico who cultivated the grape. They also maintain at the present time considerable herds of cattle, horses, etc. They are, in short, a remarkably sober and industrious race, conspicuous for morality and honesty, and very little given to quarrelling or dissipation …

Material culture

Clothing

The Puebloans are traditional weavers of cloth and have used textiles, natural fibers and animal hide in their cloth-making. Since woven clothing is laborious and time-consuming, every-day style of dress for working around the villages has been more spare. The men often wore breechcloths.

Agriculture

Corn is the most readily recognizable staple food for Pueblo peoples. The peoples of the western area were traditionally dry farmers, relying on crops that can survive the mostly arid conditions. Many types of corn, beans and squash (often described as The Three Sisters) are cultivated successfully in the area. The women made and used pottery to hold their food and water. Farmers in the eastern areas of the territory developed methods of irrigating their crops.

Religion

In Native communities of the Southwest's belief system, the archetypal deities appear as visionary beings who bring blessings and receive love. A vast collection of myths explores the relationships among people and nature, including plants and animals. Spider Grandmother and kachina spirits figure prominently in some myths.

Children led the religious ceremonies to create a more pure and holy ritual.

Pueblo prayer included substances as well as words; one common prayer material was ground-up maize—white cornmeal. A man might bless his son, or some land, or the town by sprinkling a handful of meal as he uttered a blessing. After the 1692 re-conquest, the Spanish were prevented from entering one town when they were met by a handful of men who uttered imprecations and cast a single pinch of a sacred substance.[12]

The Pueblo peoples used ritual 'prayer sticks,' which were colorfully decorated with beads, fur, and feathers. These prayer sticks (or 'talking sticks') were similar to those used by other Native American nations. By the 13th century, Puebloans used turkey feather blankets for warmth.[13]

Most of the Pueblos hold annual sacred ceremonies, some of which are now open to the public.

Religious ceremonies usually feature traditional dances that are held outdoors in the large common areas and courtyards, which are accompanied by singing and drumming. Unlike kiva ceremonies, traditional dances may be open to non-Puebloans. Traditional dances are considered a form of prayer, and strict rules of conduct apply to those who wish to attend one (e.g. no clapping or walking across the dance area or between the dancers, singers, or drummers).[14]

Since time immemorial, Pueblo communities have celebrated seasonal cycles through prayer, song, and dance. These dances connect us to our ancestors, community, and traditions while honoring gifts from our Creator. They ensure that life continues and that connections to the past and future are reinforced. [15]

Traditionally, all outside visitors to a public dance would be offered a meal afterward in a Pueblo home. Because of the numerous outside tourists who have attended these dances in the pueblos since the late 20th century, such meals are now open to outsiders by personal invitation only.

The public observances may also include a Roman Catholic Mass and processions on the Pueblo's feast day. The Pueblo's feast day is held on the day sacred to its Roman Catholic patron saint, assigned by Spanish missionaries so that each Pueblo's feast day would coincide with one of the people's existing traditional ceremonies. Some Pueblos also hold sacred ceremonies around Christmas and at other Christian holidays.

Private sacred ceremonies are conducted inside the kivas and only tribal members may participate according to specific rules pertaining to each Pueblo's religion.

List of Pueblos

New Mexico

- Acoma Pueblo — Keres language speakers. One of the oldest continuously inhabited villages in the United States. Access to mesa-top pueblo by guided tour only (available from visitors' center), except on Sept 2nd (feast day). Photography by $10 permit per camera only. Photographing of Acoma people allowed only with individual permission. No photography permitted in Mission San Esteban del Rey or of cemetery. Sketching prohibited. Video recording strictly prohibited. Video devices will be publicly destroyed if used.

- Cochiti Pueblo — Keres speakers.

- Isleta Pueblo — Tiwa language speakers. Established in the 14th century. Both Isleta and Ysleta were of Shoshonean stock. The isleta was originally Shiewhibak [16]

- Jemez Pueblo — Towa language speakers. Photography and sketching prohibited at pueblo, but welcomed at Red Rocks.

- Kewa Pueblo (Formerly Santo Domingo Pueblo) — Keres speakers. Known for turquoise work and the Corn Dance.

- Laguna Pueblo — Keres speakers. Ancestors 3000 BC, established before the 14th century. Church July 4, 1699. Photography and sketching prohibited on the land, but welcomed at San Jose Mission Church.

- Nambe Pueblo — Tewa language speakers. Established in the 14th century. Was an important trading center for the Northern Pueblos. Nambe is the original Tewa name, and means "People of the Round Earth". Feast Day of St. Francis October 4.

- Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo — Tewa speakers. Originally named O'ke Oweenge in Tewa. Headquarters of the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Council. Home of the Popé, one of the leaders of the August 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Known as San Juan Pueblo until November 2005.Taos Pueblo, view from the South

Taos Pueblo, view from the South - Picuris Pueblo, Peñasco, New Mexico — Tiwa speakers.

- Pojoaque Pueblo, Santa Fe, New Mexico — Tewa speakers. Re-established in the 1930s.

- Sandia Pueblo, Bernalillo, New Mexico — Tiwa speakers. Originally named Nafiat. Established in the 14th century. On the northern outskirts of Albuquerque.

- San Felipe Pueblo — Keres speakers. 1706. Photography and sketching prohibited at pueblo.

- San Ildefonso Pueblo, between Pojoaque and Los Alamos— Tewa speakers. Originally at Mesa Verde and Bandelier. The valuable black-on-black pottery was made famous here by Maria and Julian Martinez. Photography by $10 permit only. Sketching prohibited at pueblo. Heavily visited destination.

- Santa Ana Pueblo — Keres speakers. Photography and sketching prohibited at pueblo.

- Santa Clara Pueblo, Española, New Mexico — Tewa speakers. 1550. Originally inhabited Puyé Cliff Dwellings on Santa Clara Canyon.The valuable black-on-black pottery was developed here

- Taos Pueblo — Tiwa speakers. World Heritage Site. National Historic Landmark.

- Tesuque Pueblo Santa Fe— Tewa speakers. Originally named Te Tesugeh Oweengeh 1200. National Register of Historic Places. Pueblo closed to public. Camel Rock Casino and Camel Rock Suites as well as the actual Camel Rock are open.

- Zia Pueblo — Keres speakers. New Mexico's state flag uses the Zia sun symbol.

- Zuni Pueblo — Zuni language speakers. First visited 1540 by Spanish. Mission 1629

Arizona

- Hopi Tribe Nevada-Kykotsmovi — Hopi language speakers. Area of present villages settled around 700 AD

Texas

- Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, El Paso, Texas —originally Tigua (Tiwa) speakers. Also spelled 'Isleta del Sur Pueblo'. This Pueblo was established in 1680 as a result of the Pueblo Revolt. Some 400 members of Isleta, Socorro and neighboring pueblos were forced out or accompanied the Spaniards to El Paso as they fled Northern New Mexico.[18] The Spanish fathers established three missions (Ysleta, Socorro, and San Elizario) on the Camino Real between Santa Fe and Mexico City. The San Elizario mission was administrative (that is, non Puebloan).

- Some of the Piro Puebloans settled in Senecu, and then in Socorro, Texas, adjacent to Ysleta (which is now within El Paso city limits). When the Rio Grande flooded the valley or changed course, as it commonly has over the centuries, these missions have sometimes been associated with Mexico or with Texas due to the changes. Socorro and San Elizario are still separate communities; Ysleta has been annexed by El Paso.

- The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians are descended from the Yaqui or "Yoeme" people, the most southern of the Pueblo peoples of the Cahitan dialect. They were prevalent throughout the entire southwestern states of Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico; and in Texas, Arizona, and California of the United States. The Texas Band are descendants of Mountain Yaqui fighters who fled to Texas in 1870, after having killed Mexican soldiers in the State of Sonora. Many of their descendant families organized as a band with self-government in 2001; they have been recognized as a tribe by a legislative resolution of the state of Texas.[19] all members have documentation of Yaqui ancestry dating to Yaqui Territory of the 1700s.

Endonyms and Exonyms

Although most present-day pueblos are known by their Spanish or anglicized Spanish name, most Pueblos have a unique name in each of the different languages spoken in the area. The names used by each Pueblo to refer to their village (endonyms) usually differs from those given to them by outsiders (their exonyms), including by speakers of other Puebloan languages. Centuries of trade and intermarriages between the groups are reflected in the names given to the same Pueblo in each of the languages. The table below contains the names of the New Mexican pueblos and Hopi using the official or practical orthographies of the languages. Despite not being a Puebloan language, Navajo names are also included due to prolonged contact between them and the several Pueblos.

| English/Spanish Name | Endonym [6] | Navajo [20] | Keres [6] | Tewa [6][2] | Tiwa [6][2] | Towa [2][21] | Hopi [22] | Zuni [6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoma | Aak’u | Haak’oh | endonym | Téwigeh Ówîngeh | T’oławei | Totyagi’i | Ákookavi | Haku: |

| Cochiti | Kuutietyu | Tǫ́ʼgaaʼ | K’uute’geh Ówîngeh | Kotəava | Ky’ǽǽtɨɨgi’i | Kwitsi | Kochuti | |

| Laguna | K’awaika | Tó Łání | K’u’kw’áayé Ówîngeh | Powhiæba | Ky’óówe’egi’i | Kawaika’a | Ky’ana Łana | |

| San Felipe | Kaatishtya | Dibé Łizhiní | Nąnwheve Ówîngeh | P’atəak | Kwilegi’i | Katistsa | Wep-łabatts’i | |

| Santa Ana | Tamaiya | Dahmi | Shadegeh Ówîngeh | Patuthaa | Tɨ̨́dægi’i | Tamaya | Damaiya | |

| Santo Domingo | Kewa | Tó Hájiiloh | Taywheve Ówîngeh | Tuwita | Tǽwigi’i | Tuuwí’i | Wehk’ana | |

| Zia | Tsi’ya | Tł’ógí | Sia Ówîngeh | Təanąbak | Sæyakwa | Tsiya’ | Tsia'a | |

| Nambé | Nambe’e Ôwîngeh | (Not Available) | Nomɨ’ɨ | endonym | Nammuluva | Pashiukwa | Tuukwive’ Tewa | (Not Available) |

| Pojoaque | P’ohsųwæ̨geh Ówîngeh | (Not Available) | P’ohwakedze | As’ona’ | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | |

| San Idelfonso | P’ohwhogeh Ówîngeh | Tsétaʼ Kin | P’akwede | P’ahwia’hliap | P’ææshogi’i | Suustapna Tewa | Dawsa | |

| San Juan | Ohkwee Ówîngeh | Kin Łigaai | (Not Available) | P’akæp’al’ayą | (Not Available) | Yuupaqa Tewa | (Not Available) | |

| Santa Clara | Kha’p’oe Ówîngeh | Naashashí | Kaip’a | Haipaai | Shǽǽp’æægi’i | Nasave’

Tewa |

(Not Available) | |

| Tesuque | Tets’úgéh Ówîngeh | Tł’oh Łikizhí | Tyutsuko | Tuts’uiba | Tsota | Tuukwive’ Tewa | (Not Available) | |

| Isleta | Shiewhibak/Tsugwevaga | Naatoohó | Dyiiw’a’ane | Tsiiwheve Ówîngeh | endonym | Téwaagi’i | Tsiyawipi | K’a:shhita |

| Picuris | P’įwweltha | Tók’elé | Pikuli | P’įnwêê Ówîngeh | P’êêkwele | (Not Available) | (Not Available) | |

| Sandia | Napi’ad | Kin Łichíí | Waashuudze | P’otsą́nûû Ówîngeh | Sądéyagi’i | Payúpki | We:łuwal’a | |

| Taos | Təotho | Tówoł | Taus’ami | P’įnsô Ówîngeh | Yɨ́láta | Kwapihalu | Dopoliana | |

| Jemez | Walatɨɨwa | Mąʼii Deeshgiizh | Heem’ishiidze | Wą́ngé Ówîngeh | Hiemma | endonym | Hemisi | He:mu:shi |

| Hopi | Móókwi/Hópi | Ayahkiní | Muutyi | Khosó’on | Bukhiek | Hɨ́pé | endonym | Mu:kwi |

| Zuni | Shiwinna | Naashtʼézhí | Sɨɨniidze | Sųyų | Sunyi’inæ | Sɨnigi’i | Sí’ooki | endonym |

| Navajo People | Diné | endonym | Tene | Wǽn Sávo | (Not Available) | Ky’ælætoosh | Tasavu | A:bachu |

With the exception of Zuni, all Puebloan languages, as well as Navajo, are tonal. However, tone is not usually shown in the spelling of these languages save for Navajo, Towa and Tewa. In the table above, low tone is left unmarked in the orthography. Vowel nasalisation is shown by an ogonek diacritic below the vowel; ejective consonants are transcribed with an apostrophe following the consonant. Vowel length is shown either by doubling of the character or, in Zuni, by adding a colon.

Feast days

- January

- Pojoaque Pueblo Feast Day: December 12, January 6

- San Ildefonso Pueblo Feast Day: January 23.

- April

- Texas Band of Yaqui Indians Easter Observance Dance of the Coyotes.

- May

- San Felipe Pueblo Feast Day: May 1

- Texas Band of Yaqui Indians May 27: Recognition Celebrations

- June

- Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo Feast Day: June 24

- Sandia Pueblo Feast Day: June 13.

- Ysleta / Isleta del Sur Pueblo Feast Day: June 13.

- July

- Cochiti Pueblo Feast Day: July 14

- San Felipe Pueblo Feast Day: July 25

- Santa Ana Pueblo Feast Day: July 26

- August

- Picuris Pueblo Feast Day: August 10

- Jemez Pueblo Feast Day: August 2

- Santo Domingo Pueblo Feast Day: August 4

- Santa Clara Pueblo Feast Day : August 12

- Zia Pueblo Feast Day: August 15

- September

- Acoma Pueblo Feast Day of San Esteban del Rey: September 2

- Laguna Pueblo Feast Day: September 19

- Taos Pueblo Feast Day: September 30

- October

- Nambe Pueblo Feast Day of St. Francis: October 4

- November

Jemez Pueblo Feast Day: November 12

- Tesuque Pueblo Feast Day of San Diego: November 12

- December

- Pojoaque Pueblo Feast Day: December 12, January 6

- Variable

- Isleta Pueblo Feast Days

Pottery

There is a short history of creating pottery among the various Pueblo communities. Mera, in his discussion of the "Rain Bird" motif, a common and popular design element in pueblo pottery states that, "In tracing the ancestry of the "Rain Bird" design it will be necessary to go back to the very beginnings of decorated pottery in the Southwest to a ceramic type which as reckoned by present-day archaeologists came into existence some time during the early centuries of the Christian era".[23]

-

Zuni olla, 19th century, at Stanford University

-

San Ildefonso Pueblo Black-on-Black Pottery Bowl by Maria Martinez

-

Zuni owl figure, University of British Columbia

-

Acoma Pueblo, pottery jar, Field Museum

-

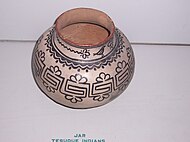

Tesuque Pueblo, Pottery, Field Museum

-

Bird effigy, pottery, Cochiti Pueblo. Field Museum

-

Pottery Bowl, Jemez Pueblo, Field Museum, Chicago

-

Ancestral Hopi bowl, ca. 1300 AD

See also

- Ancient dwellings of Pueblo peoples

- Ancient Pueblo peoples

- Arizona Tewa

- Carol Jean Vigil

- Cuisine of the Southwestern United States

- Hopi

- Tanoan languages

- Navajo people

- New Mexican cuisine

- New Mexico music

- Paquime

- Pueblo

- Pueblo music

- Pueblo Revolt

- Tewa people

- Tiwa

- Keresan languages

- Zuni people

References

- ^ a b 1923-2011., Sando, Joe S., (1992). Pueblo nations : eight centuries of Pueblo Indian history (1st ed ed.). Santa Fe, N.M.: Clear Light. ISBN 0940666170. OCLC 24174245.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Sutton, Logan (2014). Kiowa-Tanoan: A Synchronic and Diachronic Study. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico.

- ^ JSTOR summary, Harry Hoijer,"American Indian Linguistics in the Southwest: Comments" American AnthropologistNew Series, Vol. 56, No. 4, Southwest Issue (Aug., 1954), pp. 637-639

- ^ Fred Russell Eggan, Social Organization of the Western Pueblos, University of Chicago Press, 1950.

- ^ a b c Paul Kirchhoff, "Gatherers and Farmers in the Greater Southwest: A Problem in Classification", American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 56, No. 4, Southwest Issue (August 1954), pp. 529-550

- ^ a b c d e f C., Sturtevant, William (<1978-2008>). Handbook of the North American Indians. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0160045770. OCLC 13240086.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cordell, Linda S. Ancient Pueblo Peoples, St. Remy Press and Smithsonian Institution (1994); ISBN 0-89599-038-5.

- ^ Nash, Gary B. Red, White and Black: The Peoples of Early North America Los Angeles (2015). Chapter 1, p. 4 {ISBN-13|978-0205887590}

- ^ Paul Horgan (1954), Great River',' vol. 1, p. 286. Library of Congress card number 54-9867.

- ^ Po'pay dedication

- ^ Gregg, J. 1844. Commerce of the Prairies, Chapter 14: "The Pueblos", p. 55. New York: Henry G. Langley.

- ^ Paul Horgan, Great River p. 158

- ^ "Turkeys domesticated not once, but twice", physorg.com; accessed September 2015.

- ^ "Pueblo religious etiquette".

- ^ "Indian Pueblo Cultural Center".

- ^ "Isleta Pueblo". Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) VIII

- ^ 19 Pueblos

- ^ Newadvent.org

- ^ Resolution SR#989

- ^ 1912-2007., Young, Robert W., (1980). The Navajo language : a grammar and colloquial dictionary. Morgan, William, 1917-2001,, Young, Robert W., 1912-2007., Young, Robert W., 1912-2007. (1st ed ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826305369. OCLC 6597162.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yumitani, Yukihiro (1998). A Phonology and morphology of Jemez Towa. University of Kansas Dissertation.

- ^ Roy., Albert, (1985). A concise Hopi and English lexicon. Shaul, David Leedom. Philadelphia: J. Benjamins. ISBN 9027220158. OCLC 777549431.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mera, H.P., Pueblo Designs: 176 Illustrations of the "Rain Bird, Dover Publications, Inc, 1970, first published by the Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, New Mexico (1937), p. 1

References

- Fletcher, Richard A. (1984). Saint James' Catapult: The Life and Times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford University Press. (on-line text, ch. 1)

- Florence Hawley Ellis An Outline of Laguna Pueblo History and Social Organization Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 15, No. 4 (Winter, 1959), pp. 325–347

- Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, NM offers information from the Pueblo people about their history, culture, and visitor etiquette.

- Gram, John R. (2015). Education at the Edge of Empire: Negotiating Pueblo Identity in New Mexico's Indian Boarding Schools. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Paul Horgan, Great River: The Rio Grande in North American History. Vol. 1, Indians and Spain. Vol. 2, Mexico and the United States. 2 Vols. in 1. Wesleyan University Press 1991.

- Pueblo People, Ancient Traditions Modern Lives, Marica Keegan, Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1998, profusely illustrated hardback, ISBN 1-57416-000-1

- Elsie Clews Parsons, Pueblo Indian Religion (2 vols., Chicago, 1939).

- Ryan D, A. L. Kroeber Elsie Clews Parsons American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 45, No. 2, Centenary of the American Ethnological Society (Apr. - Jun., 1943), pp. 244–255

- Parthiv S, ed. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 9, Southwest. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1976.

- Julia M. Keleher and Elsie Ruth Chant (2009). THE PADRE OF ISLETA The Story of Father Anton Docher. Sunstone press Publishing.

External links

- Kukadze'eta Towncrier, Pueblo of Laguna

- Pueblo of Isleta

- Pueblo of Laguna

- Pueblo of Sandia

- Pueblo of Santa Ana

- The SMU-in-Taos Research Publications digital collection contains nine anthropological and archaeological monographs and edited volumes representing the past several decades of research at the SMU-in-Taos (Fort Burgwin) campus near Taos, New Mexico, including Papers on Taos archaeology and Taos archeology