Kingdom of Luwu

Luwu ᨒᨘᨓᨘ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Status | Part of Indonesia | ||||||||

| Capital | Wara | ||||||||

| Common languages | Buginese | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Datu | |||||||||

• 1000 | Batara Guru | ||||||||

• 1587-1615 | Andi Pattiware’ | ||||||||

• 1935-1965 | Andi Djemma | ||||||||

• 2012-Present | La Maradang Andi Mackulau | ||||||||

| Currency | No official currency, the Barter system was used | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | (as Luwu Regency) | ||||||||

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

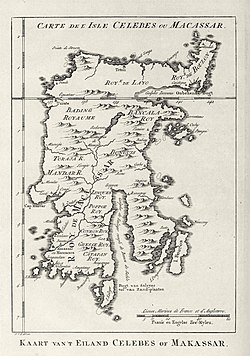

The Kingdom of Luwu (also Luwuq or Wareq) is generally thought to be the oldest kingdom in South Sulawesi. In 1889, the Dutch Governor of Makassar placed Luwu's heyday between the 10th and 14th centuries, but offered no evidence. The La Galigo, an epic tradition of oral origin, is the likely inspiration of Braam Morris’ dating. The La Galigo depicts a vaguely defined world of coastal and riverine kingdoms whose economies are based on trade. Two of the important centers of this world are Luwu and the kingdom of Cina (pronounced Cheena, identical in Indonesian pronunciation to China), which lay in the western Cenrana valley, with its palace centre near the hamlet of Sarapao in Pamanna district. The incompatibility of the La Galigo's trade-based political economy with those of the agricultural kingdoms in which many of the episodes of the La Galigo are set, led Braam Morris and later historians to posit an intervening period of chaos to separate the two periods chronologically.[1]

Archaeological and textual research carried out since the 1980s has undermined this chronology.[2] Extensive surveys and excavations in Luwu have revealed that it approximately 100 years younger than the earliest agricultural kingdoms of the southwest peninsula. There is no evidence of Bugis settlement in Luwu before this date, not is there anywhere evidence of a period of chaos preceding the origins of the agricultural kingdoms. The earliest evidence for the start of complex societies in South Sulawesi lies in the region around the central lakes, as John Crawfurd suggested,[3] and on the south coast of the peninsula. Several thirteenth-century AMS radiocarbon dates have now been obtained from palace sites in Wajo and Soppeng, together with thirteenth to fourteenth century Jizhou sherdage from northern China.[4][5]

The new understanding is that Bugis speaking settlers from the western Cénrana valley began to settle along the coastal margins of Luwu around the year 1300. The Gulf of Bone is not a Bugis-speaking area: it is a thinly populated region of great ethnic diversity, and Bugis speakers make up a small percentage of its population. Speakers of Pamona, Padoe, Toala, Wotu and Lemolang languages live on the coastal lowlands and foothills, while the highland valleys are home to groups speaking various other Central and South Sulawesi languages. The Bugis are found almost solely along the coast, to which they have evidently migrated in order to trade with Luwu's indigenous peoples. It is clear both from archaeological and textual sources that Luwu was a Bugis-led coalition of various ethnic groups, united by trading relationships. The main centres of Bugis settlement were Bua, Ponrang, Malangke (or Wareq) and possibly Cerekang near Malili. Around 1620 the palace centre of Luwu moved from Malangke to Palopo following an economic collapse.

The migration after circa 1300 of small numbers of Bugis from the central lakes area was evidently lead by members of Cina's ruling family, a loose coalition of high-ranking families claiming a common ancestry that ruled settlements across the Cenrana and Walennae valleys. This can be surmised from the fact that Luwu and Cina share the same founding myth of a tomanurung or heavenly-decended being called Simpurusia, and that that both versions of this myth state that Simpurusia descended at Lompoq, now in Sengkang. Cina was absorbed in the sixteenth century by Soppeng and Wajo, after which Cina's ruling family effectively vanished. However, this ancient line of rulers continued in Luwu down to the abolition of kingdoms in 1954. It is likely that the widespread belief that Luwu is older than other South Sulawesi kingdoms stems partly from this fact, and accounts for the precedence of the Datu Luwu over all former ruling families.

Luwu's political economy was based on the smelting of iron ore brought down, via the Lémolang-speaking polity of Baebunta, to Malangke on the central coastal plain. Here the smelted iron was worked into weapons and agricultural tools and exported to the rice-growing southern lowlands. This brought the kingdom great wealth, and by the 14th century Luwu had become the feared overlord of large parts of the southwest and southeast peninsula. The first ruler for which we have any real information was Dewaraja (ruled c. 1495-1520). Stories current today in South Sulawesi tell of his aggressive attacks on the neighboring kingdoms of Wajo and Sidenreng. Luwu's power was eclipsed in the 16th century by the rising power of the southern agrarian kingdoms, and its military defeats are set out in the Chronicle of Bone.

On 4 or 5 February 1605, Luwu's ruler, La Patiwareq, Daeng Pareqbung, became the first South Sulawesi ruler to embrace Islam, taking as his title Sultan Muhammad Wali Mu’z’hir (or Muzahir) al–din. He is buried at Malangke and is referred to in the chronicles as Matinroe ri Wareq, ‘He who sleeps at Wareq’, the former palace–centre of Luwuq. His religious teacher, Dato Sulaiman, is buried nearby. Around 1620, Malangke was abandoned and a new capital was established to the west at Palopo. It is not known why this sprawling settlement, the population of which may have reached 15,000 in the 16th century, was suddenly abandoned: possibilities include the declining price of iron goods and the economic potential of trade with the Toraja highlands.

By the 19th century, Luwu had become a backwater. James Brooke, later Rajah of Sarawak, wrote in the 1830s that ‘Luwu is the oldest Bugis state, and the most decayed [...] Palopo is a miserable town, consisting of about 300 houses, scattered and dilapidated [...] It is difficult to believe that Luwu could ever have been a powerful state, except in a very low state of native civilisation.’[6] In the 1960s Luwu was a focus of an Islamic rebellion led by Kahar Muzakkar. Today the former kingdom is home to the world's largest nickel mine and is experiencing an economic boom fueled by inward migration, yet it still retains much of its original frontier atmosphere.

See also

References

- ^ Pelras, C. 1996. The Bugis. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ Bulbeck, D. and I. Caldwell. 2000. Land of iron; The historical archaeology of Luwu and the Cenrana valley. Hull: Centre for South East Asian Studies, University of Hull.

- ^ Crawfurd, John, "S", A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries, Cambridge University Press, pp. 371–424, ISBN 9781139199070, retrieved 2019-09-28

- ^ Bulbeck, David; Caldwell, Ian (2008-03). "ORYZA SATIVAAND THE ORIGINS OF KINGDOMS IN SOUTH SULAWESI, INDONESIA:Evidence from Rice Husk Phytoliths". Indonesia and the Malay World. 36 (104): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13639810802016117. ISSN 1363-9811.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hasanuddin. 2015. Kebudayaan megalitik di Sulawesi Selatan dan hubungannya dengan Asia Tenggara. PhD thesis, Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- ^ Brooke, J. 1848. Narrative of events in Borneo and Celebes down to the occupation of Labuan. From the Journals of James Brooke, Esq. Rajah of Sarawak and Governor of Labuan [. . .] by Captain Rodney Mundy. London: John Murray.