Panic of 1893: Difference between revisions

commas for appositive |

→Causes: added re railroad expansion the collapse of the Reading |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Causes== |

==Causes== |

||

The 1880s had seen a period of remarkable economic expansion in the United States. In time, the expansion became driven by speculation, much like the "tech bubble" of the late 1990s, except that the preferred industry was railroads. Railroads were vastly over-built, and many companies tried to take over many others, seriously endangering their own stability so to do. One of the first signs of trouble was the bankruptcy of the [[Reading Company|Philadelphia and Reading Railroad]], which had greatly over-extended itself, on [[February 23]], [[1893]].<ref>James L. Holton, ''The Reading Railroad: History of a Coal Age Empire'', Vol. I: The Nineteenth Century, pp. 323-325, citing Vincent Corasso, ''The Morgans''.</ref> |

|||

As concern of the state of the economy worsened, people rushed and caused [[bank run]]s. The credit crunch rippled through the economy. Smart european investors only took payment in gold, weakening the US gold reserve, which further dropped the US dollar's value. People attempted to redeem [[Silver Certificate|silver notes]] for gold; ultimately the statutory limit for the minimum amount of gold in federal reserves was reached and U.S. notes could no longer be successfully redeemed for gold. The investments during the time of the Panic were heavily financed through bond issues with high interest payments. The [[National Cordage Company]] (the most actively traded stock at the time) went into [[Bankruptcy|receivership]] as a result of its bankers calling their loans in response to rumors regarding the NCC's financial distress. |

As concern of the state of the economy worsened, people rushed and caused [[bank run]]s. The credit crunch rippled through the economy. Smart european investors only took payment in gold, weakening the US gold reserve, which further dropped the US dollar's value. People attempted to redeem [[Silver Certificate|silver notes]] for gold; ultimately the statutory limit for the minimum amount of gold in federal reserves was reached and U.S. notes could no longer be successfully redeemed for gold. The investments during the time of the Panic were heavily financed through bond issues with high interest payments. The [[National Cordage Company]] (the most actively traded stock at the time) went into [[Bankruptcy|receivership]] as a result of its bankers calling their loans in response to rumors regarding the NCC's financial distress. |

||

As the demand for Silver and Silver notes fell, its price and value dropped. Holders worried about a loss of face value of bonds, and many became worthless. |

As the demand for Silver and Silver notes fell, its price and value dropped. Holders worried about a loss of face value of bonds, and many became worthless. |

||

Revision as of 19:16, 22 May 2008

The Panic of 1893 was a serious economic depression in the United States and began in 1893. This panic was an extension of the Panic of 1873, and like that earlier crash, was caused by railroad overbuilding and shaky railroad financing which set off a series of bank failures. Compounding market overbuilding and a railroad bubble was a run on the gold supply and a policy of using both gold and silver metals as a peg for the US Dollar value. The Panic of 1893 was the worst economic crisis to hit the nation in its history to that point and, some argue, as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s.

| Year | Lebergott | Romer |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 1891 | 5.4 | 4.8 |

| 1892 | 3.0 | 3.7 |

| 1893 | 11.7 | 8.1 |

| 1894 | 18.4 | 12.3 |

| 1895 | 13.7 | 11.1 |

| 1896 | 14.5 | 12.0 |

| 1897 | 14.5 | 12.4 |

| 1898 | 12.4 | 11.6 |

| 1899 | 6.5 | 8.7 |

| 1900 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

Causes

The 1880s had seen a period of remarkable economic expansion in the United States. In time, the expansion became driven by speculation, much like the "tech bubble" of the late 1990s, except that the preferred industry was railroads. Railroads were vastly over-built, and many companies tried to take over many others, seriously endangering their own stability so to do. One of the first signs of trouble was the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which had greatly over-extended itself, on February 23, 1893.[1]

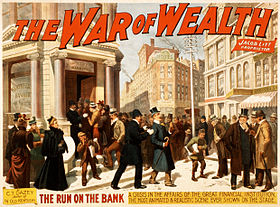

As concern of the state of the economy worsened, people rushed and caused bank runs. The credit crunch rippled through the economy. Smart european investors only took payment in gold, weakening the US gold reserve, which further dropped the US dollar's value. People attempted to redeem silver notes for gold; ultimately the statutory limit for the minimum amount of gold in federal reserves was reached and U.S. notes could no longer be successfully redeemed for gold. The investments during the time of the Panic were heavily financed through bond issues with high interest payments. The National Cordage Company (the most actively traded stock at the time) went into receivership as a result of its bankers calling their loans in response to rumors regarding the NCC's financial distress. As the demand for Silver and Silver notes fell, its price and value dropped. Holders worried about a loss of face value of bonds, and many became worthless.

A series of bank failures followed, and the price of silver fell. The Northern Pacific Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad all failed. This was followed by the bankruptcy of many other companies; in total over 15,000 companies and 500 banks failed (many in the west). About 17%-19% of the workforce was unemployed at the Panic's peak. The huge spike in unemployment, combined with the loss of life savings by failed banks, meant that a once secure middle class could not meet their mortgage obligations. As a result, many walked away from recently built homes. From this, the sight of the vacant Victorian (haunted) house entered the American mindset.[2]

Effects

The severity was great in all industrial cities and mill towns. Farm distress was great because of the falling prices for export crops such as wheat and cotton. Coxey's Army was a highly publicized march of unemployed men from Ohio and Pennsylvania to Washington to demand relief. A severe wave of strikes took place in 1894, most notably the Midwestern bituminous coal strike of the spring, which led to violence in Ohio. Even more serious was the Pullman Strike, which shut down much of the nation's transportation system in July, 1894.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, perhaps along with the protectionist McKinley Tariff of 1890, have been partially blamed for the panic. Passed in response to a large overproduction of silver by western mines, the Sherman Act required the U.S. Treasury to purchase silver using notes backed by either silver or gold. Politically the Democrats and President Cleveland were blamed for the depression. The Democrats and Populists lost heavily in the 1894 elections, which marked the largest Republican gains in history.

Many of the western silver mines closed, and a large number were never re-opened. A significant number of western mountain narrow-gauge railroads, which had been built to serve the mines, also went out of business. The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad stopped its ambitious plan, then under way, to convert its system from narrow-gauge to standard-gauge.

The depression was a major issue in the debates over Bimetallism. The Republicans blamed the Democrats and scored a landslide victory in the 1894 state and Congressional elections. The Populists lost most of their strength and had to support the Democrats in 1896. The presidential election of 1896 was fought on economic issues and was marked by a decisive victory of the pro-gold, high-tariff Republicans led by William McKinley over pro-silver William Jennings Bryan.

Many people abandoned their homes and came west. The growing railway towns in the west of Seattle, Portland, Salt Lake City, Denver, San Francisco and Los Angeles took in the populations--as did many smaller centers.

The U.S. economy finally began to recover in 1896. After the election of Republican McKinley, confidence was restored with the Klondike gold rush and the economy began 10 years of rapid growth, until the Panic of 1907.

References

Primary sources

- Appleton’s Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events for the Year (annual 1893-1897).

- Baum, Lyman Frank and W. W. Denslow. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).

- Brice, Lloyd Stephens, and James J. Wait. “The Railway Problem.” North American Review 164 (March 1897): 327–48. online at MOA Cornell.

- Cleveland, Frederick A. “The Final Report of the Monetary Commission.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 13 (January 1899): 31–56 (JSTOR).

- Closson, Carlos C. Jr. "The Unemployed in American Cities." Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 8, no. 2 (January 1894) 168-217 (JSTOR).

- Closson, Carlos C. Jr. "The Unemployed in American Cities," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 8, no. 4 (July 1894): 443-477 (JSTOR).

- Fisher, Willard. "‘Coin’ and His Critics." Quarterly Journal of Economics 10 (January 1896): 187–208 (JSTOR).

- Harvey, William H. Coin’s Financial School (1894), 1963 (Introduction by Richard Hofstadter).

- Noyes, Alexander Dana. “The Banks and the Panic.” Political Science Quarterly 9 (March 1894): 12–28 (JSTOR).

- Romer, Christina. "Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data." Journal of Political Economy 94, no. 1. (1986): 1-37.

- Shaw, Albert. “Relief for the Unemployed in American Cities.” Review of Reviews 9 (January and February 1894): 29–37, 179–91.

- Stevens, Albert Clark. “An Analysis of the Phenomena of the Panic in the United States in 1893.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 8 (January 1894): 117–48 (JSTOR).

Secondary sources

- Barnes, James A. John G. Carlisle: Financial Statesman (1931).

- Barnes, James A. “Myths of the Bryan Campaign.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 34 (December 1947): 383–94 (JSTOR).

- Destler, Chester McArthur. American Radicalism, 1865–1901 (1966).

- Dewey, Davis Rich. Financial History of the United States (1903).

- Dighe, Ranjit S. ed. The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory (2002).

- Dorfman, Joseph Harry. The Economic Mind in American Civilization. (1949). vol 3.

- Faulkner, Harold Underwood. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890–1900. (1959).

- Feder, Leah Hanna. Unemployment Relief in Periods of Depression … 1857-1920 (1926).

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960(1963).

- Hoffmann, Charles. "The Depression of the Nineties." Journal of Economic History 16 (June 1956): 137–64 (JSTOR).

- Hoffmann, Charles. The Depression of the Nineties: An Economic History (1970).

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: 1888-1896 (1971).

- Kirkland, Edward Chase. Industry Comes of Age, 1860–1897 (1961).

- Lauck, William Jett. The Causes of the Panic of 1893 (1907).

- Lindsey, Almont. The Pullman Strike 1942.

- Littlefield, Henry M. "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism" American Quarterly Vol. 16, No. 1 (Spring, 1964), pp. 47-58 (JSTOR).

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage. 1932, Pulitzer Prize.

- Rezneck, Samuel S. “Unemployment, Unrest, and Relief in the United States during the Depression of 1893–97.” Journal of Political Economy 61 (August 1953): 345 (JSTOR).

- Ritter, Gretchen. Goldbugs and Greenbacks: The Anti-Monopoly Tradition and the Politics of Finance in America (1997)

- Ritter, Gretchen. "Silver slippers and a golden cap: L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and historical memory in American politics." Journal of American Studies (August 1997) vol. 31, no. 2, 171-203.

- Rockoff, Hugh. "The 'Wizard of Oz' as a Monetary Allegory," Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 739-60 (JSTOR).

- Schwantes, Carlos A. Coxey’s Army: An American Odyssey (1985).

- Shannon, Fred Albert. The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860–1897 (1945).

- Steeples, Douglas, and David O. Whitten. Democracy in Desperation: The Depression of 1893 (1998).

- White; Gerald T. The United States and the Problem of Recovery after 1893 1982.

- Whitten, David. EH.NET article on the Depression of 1893