Highlander Folk School

The Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market Tennessee–formerly the Highlander Folk School–and the ideas associated with it are woven throughout SNCC’s history. It was founded in 1932 by Myles Horton, a native Tennessean who wanted to create an educational institution for the poor and working people of Appalachia. While overseas visiting rural folk schools in Denmark in the early 1930s, he realized that the type of education he was looking for began and ended with the lived experiences of its students. “What you must do is go back, get a simple place, move in and you are there. The situation is there … [the school] will build its own structure and take its own form,” he wrote on Christmas Eve, 1931.

Thorsten and Myles Horton, sitting on left, watching Rosa Parks, standing and speaking at Highlander Folk School, undated, Highlander Records, WHS

So, when he returned to the United States, Horton rented a small farm on a mountain top near Monteagle, Tennessee, which would remain the home of the Highlander Folk School until the state revoked its license in 1961 in retaliation for the school’s civil rights activities. At first, Highlander’s small staff failed to make much headway into the surrounding communities. “We ended up doing what most people do when they come to a place like Appalachia,” Horton recalled. “We saw problems that we thought we had the answers to, rather seeing the problems and the answers that the people had themselves.”

Highlander learned quickly from its early mistakes and over the next thirty years dedicated itself to a model of democratic education that was rooted in the lives and problems of its students. The school used small group discussions and workshops to enable students to delve into their own issues and use their collective knowledge to find solutions. Highlander’s teaching staff encouraged participants to go home and put what they learned into practice. “We try to stimulate and enhance and set in motion a yeasty, self-multiplying process,” explained Horton. Highlander wanted empower students to become agents of social change.

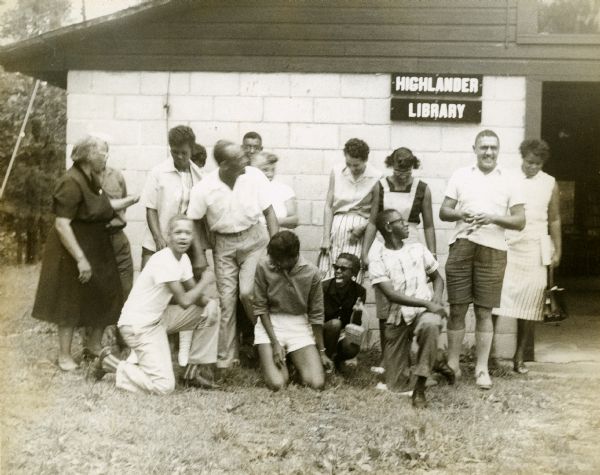

A photograph of Septima Clark (far left) with a group of students outside of Highlander’s library, undated, Highlander Research and Education Center Records, WHS

In the 1950s, the folk school made a commitment to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. It opened its doors to Black activists from across the South, making it one of the region’s only fully integrated schools. Septima Clark began the citizenship education program that would eventually migrate to SCLC at Highlander. It was retreat space for SCLC.

When the sit-in movement erupted in 1960, Highlander became an important training ground for young Black activists. Even before SNCC’s founding conference, Highlander hosted meetings of sit-in activists. The old Black hymn, “I’ll overcome” was reshaped into “We Shall Overcome” by sit-in students meeting at Highlander in March 1960.

Many of the young SNCC workers looked up to Myles Horton and other Highlander staff as mentors. Horton was in the background at many SNCC meetings, offering advice and guidance when called upon.

In June 1962, SNCC’s Bob Moses, Curtis Hayes, Sam Block, and Hollis Watkins–SNCC’s earliest staff in Mississippi– piled into Amzie Moore’s 1949 Packard and headed to Knoxville, in preparation for an expansion of voter registration work. Horton drew on his network of seasoned organizers to talk with the young SNCC workers. One woman warned the SNCC organizers to avoid local class snobberies; another advised them against bickering with other civil rights organizations. Most of all, they were told the listen and learn from the people they sought to organize. When the week-long workshop ended, the SNCC workers were flush with new ideas and perspectives about community organizing and local empowerment.

Sources

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2008), 324-329.

Aimee Isgrig Horton, The Highlander Folk School: A History of Its Major Programs, 1932-1961 (New York: Carlson Publishing Inc., 1989).

Myles Horton, The Myles Horton Reader: Education for Social Change, edited by Dale Jacobs (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2003).

Myles Horton with Judith Kohl and Herbert Kohl, The Long Haul: A Biography (New York: Teachers College Press, 1998).

Aldon Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change (New York: The Free Press, 1984).

Jon Hale, “Early Pedagogical Influences on the Mississippi Freedom Schools: Myles Horton and Critical Education in the Deep South,” American Educational History Journal (2007), 315-325.

Barbara Thayer-Bacon, “An Exploration of Myles Horton’s Democratic Praxis: The Highlander Folk School,” Journal of Educational Foundations (Spring 2014), 5-25.

Sue Thrasher, “Fifty Years with Highlander,” Journal of the Southern Regional Council (1982), 4-9.