Where does canned laughter come from – and where did it go?

BBC

BBCThe history of ‘the laugh track’ says much about what the makers of television thought of their audiences, writes Jennifer Keishin Armstrong.

Charley Douglass didn’t like the laughter he was hearing.

The sound engineer, who was working at CBS in the early days of television, hated that the studio audiences on the US TV channel’s shows laughed at the wrong moments, didn’t laugh at the right moments, or laughed too loudly or for too long. So he took a page from radio producers before him who had pioneered the use of recorded laughter, most notably when Bing Crosby began pre-recording his show – which allowed his engineers to add or subtract the laughs in post-production.

CBS

CBSDouglass copped the technique for CBS and began amping up or tamping down laughter recordings according to the effect he wanted, rather than relying on audiences’ natural reactions. Soon he was on a mission, building a machine full of taped laugh tracks (according to historians, recorded mainly during dialogue-free sequences in variety a programme, The Red Skelton Show) that would evolve to become the industry standard after Douglass’s laugh-track debut in 1950 on The Hank McCune Show.

The idea of ‘the laugh track’ spread quickly through the new medium—and caused immediate controversy that would last until modern times. Actor and producer David Niven sniffed in a 1955 interview, "The laugh track is the single greatest affront to public intelligence I know of, and it will never be foisted on any audience of a show I have some say about." But TV producers remained wed to the idea of providing some sort of audience reaction to make the viewing experience more communal; after all, audiences were still largely used to enjoying their entertainment via live performance or in the cinema, both of which provided fellow laughers. The industry’s ambivalence toward the practice was best summed up in a cursory Billboard magazine item in 1955: “TV production chief Babe Unger hates canned laugh tracks, but thinks audience reaction is necessary for The Eddie Cantor Comedy Theater because TV viewers expect an audience to be there.”

CBS

CBSIn the five intervening decades, however, the laugh track has gone from ubiquitous to a laughingstock in itself. That’s partly because our attitude toward TV comedy – and artifice – has changed. Where we once valued guffaw-inducing hijinks, we now value the so-horrifying-they’re-funny plotlines of Orange Is the New Black. Where we once valued joining the masses, now we enjoy bragging about our singular love of Bojack Horseman’s black comedy. Among the seven new half-hour comedies screening on US broadcast networks this autumn, only three – The Great Indoors, Kevin Can Wait, and Man With a Plan, all on CBS – employ laugh tracks. (CBS has built its brand on throwback, middle-of-the-road hits like The Big Bang Theory.) Perhaps even more tellingly, none of the seven Emmy nominees for outstanding comedy series use laugh tracks. What was once an essential element of the sitcom is now seen as the marker of an unsophisticated show for the masses, not something the cool kids would watch.

The world laughs with you

When Douglass first ‘invented’ the laugh track in 1950, it was intended to help the audience watch, understand and feel comfortable with a relatively new medium. TV comedies adopted canned laughter to ease their viewers into a new kind of entertainment, even for shows that were filmed without live audiences. Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz changed things when they revolutionised the sitcom in the 1950s withI Love Lucy. With this production, the couple invented the ‘multi-camera’ filming technique: they used several cameras to capture several angles at once on a soundstage, complete with a live audience full of real laughter – not one of Douglass’ derided tracks.

Soon enough, however, the medium changed again and needed those tracks right back. As TV began to move from live broadcast to videotape, the editing process introduced noticeable hiccups in the recorded laughter of the audience: it needed something to smooth it out. Even shows that needed no help getting live laughs needed a version of the laugh track. In the UK all of the BBC’s comedies, such as Are You Being Served?, had laugh tracks when The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy first screened in 1981; the producers of the show recorded one to appease the coporation’s standards and practices but dropped it right before broadcast. Such was the contempt for the laugh track at the time on both sides of the Atlantic.

NBC

NBCUS audiences’ first chance to escape the laugh track had come earlier in 1965, with the CBS comedy Hogan’s Heroes; alas, they could not shake the dreaded technology. The show was shot with a single camera – in other words, with no studio audience – but the network, nervous about the format, tested two versions: one with canned laughter and one without. Test audiences reacted better to the version with the , dooming viewers at home to many more years of recorded laughter. Douglass and his “laff box” continued to dominate throughout the next decade on shows such as Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, and The Andy Griffith Show. Even 1960s cartoons such as The Flintstonesand The Jetsons used laugh tracks, though the device made no intuitive sense in that setting – no sane viewer suffered the illusion that a human audience was had watched these animated characters. The Muppet Show, subsequently, became perhaps the first to use a laugh track to semi-artistic effect in the 1970s, simulating an audience for its puppets, who were indeed ‘playing’ the stars of their own variety show.

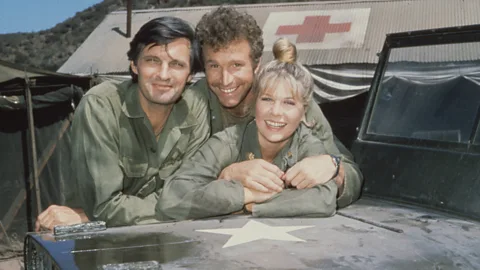

Even as comedy in the US grew more sophisticated throughout the 1970s, with shows such as All in the Family and The Mary Tyler Moore Show tackling major issues of the day, the laugh track remained. Larry Gelbart, co-creator of the war comedy M*A*S*H, wanted his show to air without laughs – “just like the actual Korean War,” he cracked. But he didn’t prevail over CBS executives, which insisted on one (though Gelbart and co-producer Gene Reynolds had the option to skip it during medical scenes). Laugh-punctuated sitcoms continued to flourish throughout the next decade, with tracks showing up on some of the best comedies of all time on both sides of the pond, from Cheersand Blackadderto Frasier and Mr Bean.

Talking down

Much of the rest of the world followed UK and US shows’ lead, employing canned laughter for sitcoms throughout most of the 20th Century. Some Latin American countries found their own way to fill the background silence, employing live audience members hired explicitly to laugh at certain moments. (They’re called reidores, or ‘laughers’.) But in the 1980s, the laugh track’s hold on UK comedies began to falter, following The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s abandonment of the device. The political satire show Splitting Image filmed its first episode with a studio audience at the insistence of broadcaster ITV, then ditched it too. Other countries, most notably Mexico and Canada, resisted the canned laughs; though Canadian shows such as Maniac Mansion and The Hilarious House of Frightenstein added them in when they were sold to US broadcasters.

US TV producers followed suit, but by the 90’s showed some resistance. The biggest American comedy hit of that decade, Seinfeld, mimicked the effect of a single camera show, using more sophisticated lighting and camera techniques and often shooting scenes on location. But its network, NBC, forced co-creators Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld (despite David’s protests) to keep the studio audience, and thus a laugh track, in the mix. Though British comedies were often filmed before audiences or had canned laughter, the dark comedies on UK TV, such as The Office, that became so popular in the early 2000s, relied more on cringes than belly laughs. And US TV, heavily influenced by the awkward style of millennial UK comedy followed suit and abandoned their laugh tracks. 30 Rock, Arrested Development, David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, and the US rendition of The Office all aired without them.

Still, with laugh tracks continuing to worm their way into some new shows, the question remains: do they serve an actual purpose, or was David Niven right to dismiss them as an “affront to public intelligence” way back in 1955? Comparative studies of the laugh track’s effectiveness have been inconclusive, suggesting, if anything, that audiences are gravitating toward the laugh-track-free approach: a 1974 study showed viewers were more likely to laugh when a show had a recorded track, while a more recent comparison of Seinfeld (with laughs) and The Simpsons (without) indicated both were equally effective. The studies could simply have come independently to different conclusions, or the time lag between them could mean we no longer need as much help knowing when to laugh at TV. In fact, internet-savvy viewers have become so wise to the laugh track that an entire genre of YouTube video has emerged to demonstrate how strange the practice is: some users edit out the laughter on major sitcoms, which become strange and creepy without it.

In Chuck Palahniuk’s 2002 novel Lullaby, he writes, “Most of the laugh tracks on television were recorded in the early 1950s. These days, most of the people you hear laughing are dead.” That’s profound, but probably not true, since TV audio engineers have been updating their reels continuously. There were times when canned laughter was so predictable, anyone in the business could predict which laugh would come next on any given show. But now it seems that the laugh track itself that may soon rest in peace.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.