What is the UK Covid inquiry and what powers does it have?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSignificant flaws in UK pandemic preparations led to more deaths and greater economic damage than should have been the case, according to the first report from the Covid inquiry.

Just under 227,000 people died in the UK from Covid between March 2020 and May 2023, when the World Health Organization declared the end of the "global health emergency".

What is the Covid public inquiry and when did it start?

The Covid inquiry was launched by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson in June 2022, more than a year after he said the government's actions would be put "under the microscope".

The announcement came after the Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice campaign said it was considering launching a judicial review over government "time-wasting".

Mr Johnson said the inquiry would cover decision-making during the pandemic by the UK government, as well as the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The first public hearings took place in June 2023.

Public inquiries are established and funded by the government and are led by an independent chair. They can compel witnesses to give evidence.

No-one is found guilty or innocent but the inquiry publishes conclusions. The government is not obliged to accept any recommendations.

Who is leading the Covid inquiry?

The inquiry is chaired by former judge and crossbench peer Baroness Hallett, who previously led the inquests into the 7 July London bombings.

She said that loss and suffering would be at the heart of the inquiry, adding it would be "firmly independent".

Piranha Photography

Piranha PhotographyShe said the inquiry would consider how decisions on limiting the spread of Covid were made and communicated, and the use of lockdowns and face coverings.

It also includes the impact of the pandemic on children and health and care sector workers, and the protection of the clinically vulnerable.

The effect on bereaved families and how the findings could be applied to other national emergencies are part of the inquiry.

What does the Covid inquiry's first report say?

At least nine reports are expected, covering everything from political decision-making to vaccines.

Publishing the first of these, inquiry chair Baroness Hallett said the UK was "ill-prepared for dealing with a catastrophic emergency, let alone the coronavirus pandemic".

"Never again can a disease be allowed to lead to so many deaths and so much suffering," she added.

The 217-page report argues the UK planned for the wrong pandemic - a mild one where spread of a new virus was inevitable - and this led to the "untested" policy of lockdown.

It says the UK government and devolved nations "failed their citizens" and that government ministers did not sufficiently challenge scientific experts.

It makes a series of recommendations for reforming the way the government approaches emergency planning across the four nations of the UK.

Baroness Hallett said she wants to see these acted on quickly, with many in place within six months or a year.

What else is the inquiry looking at?

The inquiry is split into different parts. Work has begun in several areas:

- resilience and preparedness

- decision-making and political governance in Westminster, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

- the impact on healthcare systems across the UK

- vaccines, therapeutics and antiviral treatment

- government procurement and PPE

- the care sector

- test-and-trace

- the impact on children and young people

- the government's business and financial responses

Future strands will consider:

- health inequalities

- the impact on other public services

There is no specific timescale for how long the inquiry will last, but Baroness Hallett aims to hold the final public hearings in 2026.

Scotland is holding a separate inquiry which has taken evidence from many of the same experts and politicians.

How can the public get involved in the Covid inquiry?

Anyone can share their experience through the inquiry's Every Story Matters project.

Groups representing bereaved families have urged the inquiry to ensure these voices are heard.

Members of the public can also apply to attend in person.

Public hearings are streamed on the BBC News website and the inquiry's YouTube channel,. In addition, witness transcripts are published on the inquiry website.

What did Rishi Sunak say to the inquiry?

In December 2023, former PM Rishi Sunak gave evidence during the second round of public hearings in London which focused on UK decision making and political governance.

He apologised to "all those who suffered... as a result of the actions that were taken" but denied his Eat Out to Help Out Scheme had increased Covid infections and deaths.

HM Treasury

HM TreasuryHe also rejected earlier evidence from the government's chief medical officer, Prof Sir Chris Whitty, and former chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance that they were not consulted about the policy.

What did Boris Johnson say to the inquiry?

Former PM Boris Johnson also gave evidence across two days in December 2023 as part of the second round of hearings.

The inquiry had already heard from government officials and advisers, academic experts and representatives of bereaved families, many of whom were extremely critical of his actions.

Mr Johnson began by apologising for the "pain and the loss and the suffering" experienced during the pandemic.

His comments were interrupted by protesters who were ordered to leave the room. Some members of bereaved families held up signs reading: "The dead can't hear your apologies".

He admitted mistakes were made and that "there were unquestionably things we should have done differently".

He said he took "personal responsibility for all decisions made" but insisted that ministers had done their "level best" in difficult circumstances.

Who else gave evidence during the second round of public hearings?

The second round of public hearings began in October 2023.

Former Health Secretary Matt Hancock - who previously told the inquiry the UK's pandemic strategy had been completely wrong - denied he lied to colleagues during his period in office.

But he admitted the UK should have locked down much sooner and criticised the "toxic culture" in government, for which he blamed Mr Johnson's former adviser Dominic Cummings.

Former cabinet minister Michael Gove also apologised to "victims and families who endured so much loss" but denied that Mr Johnson could not take decisions.

Sir Chris, his former deputy Prof Sir Jonathan Van-Tam and Sir Patrick revealed significant tensions between their advice to government and its political priorities, such as over Eat Out to Help Out.

PA Media

PA MediaSir Jonathan revealed he and his family had received death threats, while Sir Patrick said he had also considered resigning over abuse.

Former deputy cabinet secretary Helen MacNamara told the inquiry that she struggled "to pick one day" when Covid rules were properly followed inside a "macho" and "toxic" No 10.

EPA

EPAIn his evidence, Mr Cummings described a "dysfunctional" government with no plans to lock down the country or shield the vulnerable.

The inquiry heard scathing text messages which he sent, many of which contained offensive descriptions of ministers and officials.

He said he regretted the disastrous handling of his infamous trip to Barnard Castle during the first lockdown, but denied his actions had damaged public trust.

Who gave evidence during the first round of public hearings?

The first public hearings examining the UK's resilience and preparedness began in June 2023.

The inquiry took evidence from 69 independent experts and former and current government officials and ministers.

These included former health secretaries Jeremy Hunt and Matt Hancock, former PM David Cameron and former First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon.

Sir Chris, his predecessor Prof Dame Sally Davies and Sir Patrick also gave evidence during the first hearings.

Who gave evidence during the hearings in Northern Ireland?

Across 12 days of hearings in May 2024, the inquiry took evidence from senior politicians, including First Minister Michelle O'Neill, former Health Minister Robin Swann and former First Minister Baroness Foster.

During her evidence, Lady Foster rejected suggestions the Northern Ireland Executive "sleepwalked" into the pandemic.

Separately, Ms O'Neill apologised for attending senior republican Bobby Storey's funeral during lockdown, when she was deputy first minister.

Mr Swann said meetings he had attended on Covid rules in November 2020 had been the "lowest days" he had experienced in politics.

Other witnesses included civil servants, experts and groups representing bereaved families, older people and those with disabilities.

Who gave evidence during the hearings in Wales?

Most of the hearings in March 2024 focused on the first wave of the pandemic.

The inquiry heard from 34 witnesses, including former First Minister Mark Drakeford, who likened then Prime Minister Boris Johnson during the crisis to an "absent" football manager.

UK Covid-19 Inquiry

UK Covid-19 InquiryA number of witnesses accused the Welsh government of issuing conflicting, contradictory and confusing guidance and criticised the:

- approach to personal protection equipment (PPE)

- treatment of care home residents

- decision to close schools

The cancellation of the Wales v Scotland Six Nations rugby match, in March 2020, 24 hours before it had been due to start, was referenced several times.

Kirsten Heaven, counsel for the Covid-19 Bereaved Families Cymru:

- said there had been a "passive, slow and disjointed" early response to the pandemic

- criticised the "sloth-like urgency" of ministers' response

- called for the publication of all relevant government WhatsApp messages

Andrew Kinnier KC, representing the Welsh government, said ministers accepted some policies had not worked as well as they had hoped but their decisions had been a "reasonable response to the unprecedented challenge to civil society".

Who gave evidence during the hearings in Scotland?

The use of WhatsApp by Scottish government advisers and ministers was a key issue during the January 2024 hearings.

Former First Minister Humza Yousaf apologised unreservedly for the Scottish government's failure to hand over relevant WhatsApp messages.

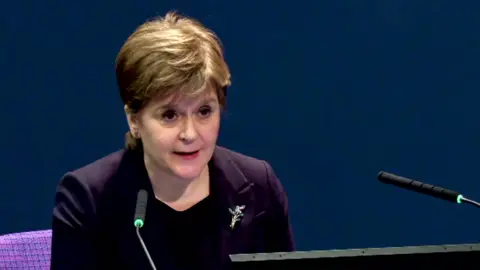

Covid Inquiry

Covid InquiryFormer First Minister Nicola Sturgeon admitted that she deleted messages from the period.

But she insisted that she did not use these informal channels to reach decisions or to have substantial discussions and that everything of relevance was available on the public record.

Ms Sturgeon was emotional during some of her evidence and appeared to fight back tears as she told the inquiry that "part of me wishes I hadn't been [First Minister during the pandemic]".