This week is National Library Week. Among other highlights this week, Monday was the second annual Right to Read Day, celebrated on the Monday of National Library Week by the American Library Association as a national day of action in support of the right to read freely.

April is also Sexual Assault Awareness Month. One might wonder what these events have in common. For that, keep reading.

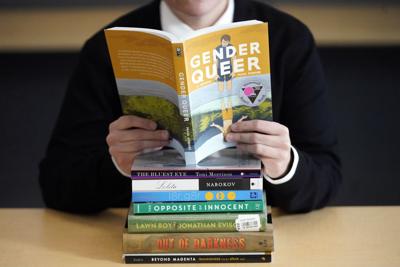

The recent investigation by Great Barrington Police into Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer: A Memoir” at W.E.B. Du Bois Regional Middle School thrust our little corner of the world into the national spotlight as it intimately acquainted us with the growing wave of censorship in the U.S. Kobabe’s memoir topped the ALA’s list of most challenged books from 2021 through 2023 because of its LGBTQ content and claims that it is sexually explicit. Many in the Berkshires rallied in support of the freedom to read and around the LGBTQ community because of the nature of this particular text, however the incident should draw our attention to what other stories — and therefore voices — are being targeted.

Of the remaining titles on the ALA’s compiled list of top 10 most challenged books of 2023, five feature references to sexual assault or abuse. Challenges to four of those titles — “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” by Stephen Chbosky, “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “Tricks” by Ellen Hopkins and “Sold” by Patricia McCormick — plainly list rape and, for Morrison’s book, incest, as reasons for the complaints. However, they also are “claimed to be sexually explicit,” as is “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson, which discusses sexual abuse. Why obfuscate depictions of sexual assault behind a characterization of “sexually explicit’’? What is hidden when we fail to name sexual violence for what it is: violence?

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, an American is sexually assaulted every 68 seconds. By writing about sexual assault and abuse, authors shed light on very real and pervasive problems that impact every community. Attempts to censor such stories as “sexually explicit” perpetuate destructive cycles wherein abusers maintain their power and control over their victims and survivors are left afraid and unsupported. Research has shown that reading fiction fuels empathy for others by imaginatively and emotionally enabling an individual to walk in another’s shoes. We need books like these and the empathy they cultivate to collectively help heal our communities and provide safety, justice and respect for all.

This is especially the case for LGBTQ and communities of color, who experience sexual assault at disproportionately higher rates than their white, heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. For example, RAINN’s data shows that 21 percent of transgender, genderqueer and nonconforming college students have been sexually assaulted, compared to 18 percent of cisgender females and 4 percent of cisgender males. Native Americans are twice as likely to experience sexual assault compared to all races. Additionally, the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence cites a nationally representative survey indicating that while almost 18 percent of white women and 7 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander women will be raped in their lifetimes, almost 19 percent of Black women, 24 percent of mixed-race women and 34 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native women will be raped during their lifetimes.

Circling back to the banned books list, 11 of the 13 top challenged books were by authors who represent or depict characters who identify as LGBTQ or come from communities of color. The ALA’s latest top challenged list for 2023 has not yet been released at the time of this writing, but overall trends are both clear and alarming. An ALA report issued in March indicated that the number of different books targeted for censorship shot up by 65 percent in 2023 compared to the previous year, reaching the highest levels ever documented by the organization. A record 4,240 unique book titles were challenged in school and public libraries, far surpassing the previous high of 2,571 unique titles in 2022.

According to ALA’s data, censorship efforts against public libraries increased considerably year over year.; the number of titles targeted at public libraries increased by 92 percent from 2022 to 2023. School libraries saw an 11 percent increase. Groups and individuals demanding the censorship of multiple titles, often dozens or hundreds at a time, drove this surge. Titles representing the voices and lived experiences of LGBTQ people and individuals of color made up 47 percent of those targeted in censorship attempts.

These statistics are disturbing from the standpoints of both intellectual freedom and fundamental human rights. Book-banning disproportionately targets the voices of marginalized individuals — the same people who also are disproportionately affected by abuse, discrimination and inequality. This concept of intersectionality, a term coined by professor Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989, points to the ways in which we must include discussions of race, gender and class when we talk about and seek to address societal injustices. The books most commonly targeted for censorship often do just that. They shed light on dark, uncomfortable truths with which we must reckon, be they sexual assault, racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, transphobia or xenophobia. These voices need to be heard if we want to live in a country that truly provides liberty and justice for all. So indeed, we must keep reading.