This article originally appeared in the October 2000 issue of Esquire under the headline “The Blessed Fisherman of Prosper, Texas.” To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

And so it came to pass that the land was redeemed. And the land was called Prosper, and it was north of Dallas, and it was a place of desert and scrub weed and tall, thirsting flowers that did wave in the breathless air. And there was sin in the land. Jezebels and Delilahs all, they did come to Prosper to set up shop, for Prosper was unincorporated, and north of Dallas, and beyond the law. And the sinful did come to Prosper and did spill their seed in the various and lubricious chalices who did wink and wave and tempt the weak from the front porches and parlors.

But then there came upon the place the godly, the righteous, and the upper management, looking for homes from which they could journey back into the city with joy in their hearts, and with a minimum of fuss and bother, except on the weekends, when traffic was hellish. And the good land did come to be valued by them (at $50,000 an acre), and the sin was squeezed out of the place, and a town beloved by its people did grow in Prosper, and prosper they did. And so it came to pass that the land was redeemed, and a pilgrim did come here to build a great house by a fishpond:

“Two seconds,” says Deion Sanders. “I give that fat one out there two seconds.”

A little ways out from the shore, a big old F-16 of a grasshopper is floundering, trying to swim back to shore. There is a stirring in the water beneath him, then a swift flash of bass and the grasshopper is gone. We are walking his property, and Sanders is flushing out great clouds of grasshoppers toward the water. Some of them fall in and get eaten, thereby fattening the bass that Sanders plans to catch as soon as his house is finished, the great pile of a place that is rising even now at the top of the slope that begins at the far bank of the fishing hole. Scripture, of course, tells us that grasshoppers are plenty good eating; John the Baptist liked his with honey. The pond comes alive with hungry fish.

“You want to describe me?” Sanders asks. “Call me a fisherman. I’ll always fish.”

Since 1989, when he came out of Florida State as a rookie cornerback, a neophyte center fielder, and a full-blown celebrity, Deion Sanders has produced as eccentric a body of work as that produced by any athlete. Having signed this season to play for the Washington Redskins, Sanders is now on his fourth stop in the NFL, which means he has played for exactly as many professional football teams as he has professional baseball teams. He is the only man ever to play in the Super Bowl and in the World Series. He’s the first two-way starter in the NFL since 1962. As he grew older, he left baseball behind, and he transformed himself into one of the great defensive backs in the history of the league, but he has remained a full-blown celebrity.

He conspired in creating his own image. He admits freely that he deliberately fabricated “Prime Time,” his gold-encrusted nom d’argent, which had its official public debut in a Sports Illustrated profile that was practically written in blackface, to help himself get rich. His entire career has been an exercise in trying to control the personality that he created. If it weren’t for Prime Time, maybe he wouldn’t have been associated willy-nilly with the I, Claudius atmosphere surrounding the Dallas Cowboys, when, in fact, the worst trouble with the law that Deion Sanders had ever had was a glorified traffic wrangle with a stadium security guard in Cincinnati and a trespassing bust that occurred when Sanders was discovered on private land where he’d gone to...fish.

If not for Prime Time, then, maybe the divorce wouldn’t have been so ugly, and maybe he wouldn’t have been there in Cincinnati contemplating, he says, putting an end to all of it. And maybe it was Prime Time who drove Deion Sanders to Jesus and drove him then to a new life with a new wife and a new baby and a new team and a new house here in Prosper. Anything’s possible. Life’s strange, and that’s what’s kept Scripture interesting all these years.

“They never give athletes credit for knowing who they are,” he says. “As an athlete, you’re in business. And I knew how to market my business. The Lord intended me to be different. He intended everyone to be different. I never tried to emulate anyone, ever. I was the first Deion Sanders, and I’ll be the last Deion Sanders.

“I created something that could command me millions of dollars, and it served its purpose. But I was playing a game, and people took it seriously.” He took it so seriously, if you believe him now, that he needed to be rescued in one of the oldest ways of all.

He says he’s Saved—capital-S Saved—from when he used to chase around and dance the hootchy-kootchy. In fact, he says they’re both saved, Deion and Prime Time. Saved from the world. Saved from each other. Saved for a good woman and a baby and for his other two children, too. Saved now for the Redskins, for whom he’ll lock up the best receivers in the league the way he did for the Falcons, 49ers, and Cowboys. (Daniel Snyder, the Redskins’ owner, has hurled money at veterans like Sanders and Bruce Smith in order to buy himself an instant Super Bowl.) Saved, says Deion, to go to Washington and play for the endless dollars of a profligate child.

This might be an act. Might just be the Prime Time shuck again, the gold covered up now in choir robes. (Sanders’s spiritual guide, the charismatic preacher T.D. Jakes, is not long on vows of poverty.) But watch him walk his land, stirring up the grasshoppers, admiring the fish, and there is a peace, an ease, a kind of steady grace that might be theological and might not be.

“I’m blessed,” says Deion Sanders. “God’s blessed me well.”

The steady hammering drifts down the hill through the heat of the afternoon, and isn’t that the damnedest thing, too? The gospel turned on its head—a bunch of carpenters come out into the desert to work for a fisherman.

All right, so it got in the way. A $30,000 golf cart will do that to a fellow’s image, especially when the golf cart has tinted windows, an ice machine, and a mist dispenser, and especially since the fellow who owns it doesn’t play golf. If Deion Sanders got defined as a heedless spendthrift, it’s only because he moved through most of his life a walking cloudburst of wealth, flashing gold and diamonds, his professional antecedents not Emlen Tunnell or Night Train Lane but Little Richard and the Reverend Ike.

“Just being a cornerback wasn’t enough,” he explains. “Being a cornerback wasn’t looked on as being a showstopper. And you’ve got to understand, I sat in my dorm room at Florida State and created that whole thing in my imagination. I just created a persona with the nickname, but you had to back it up with substance, and I think that once the media got hold of [the fact] that it was all a game for me, they got upset and tried to take things too far.

“I mean, you don’t think Eddie Murphy’s Eddie Murphy at home. Do you think Jim Carrey acts like a darn fool all day? I don’t think John Wayne sat around the house with a gun all day, and I don’t think he shot the mailman when he came through the door.”

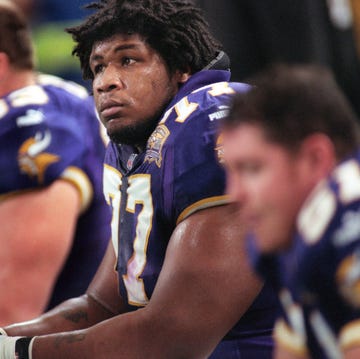

He is a bigger man than he appears on television, all sinewy angles and not inconspicuous strength, a sprinter gone bigger. But the first thing that registers about Deion Sanders—besides the fact that at thirty-three he is still youthful and handsome—is that he is disconcertingly slow to speak. He is not bubbly or bright or glib. An interview is a conversation conducted in paragraphs. But by creating Prime Time and, more important, by selling Prime Time as effectively as he did, Sanders placed at the heart of his career an intractable personal dissonance.

He played the same way. That was the odd thing about it. The gold came off and the diamonds went into the locker, but the bandanna came on and Deion Sanders lit up the football field with his talent. People who saw only the high-stepping final yards of a touchdown return missed the controlled intelligence that got him there. “If you watch him,” says Dave Campo, the former Cowboys defensive coordinator to whom Jerry Jones has handed the head-coaching job this season, “you will see this guy do things that nobody else can do. Nobody.”

It is quite possible that Sanders is the best pass defender who has ever played the game. As fast as he is down the field, he is even faster at those five- and ten-yard sprints needed to close on the ball. His matchups with the 49ers’ Jerry Rice were breathless, electric things, the finest man-to-man confrontations the NFL had seen since Sam Huff rang hats with Jim Brown back in the dim times before Chris Berman. He is smart and he is canny. He will bait quarterbacks by laying off receivers just enough, then close the distance like a swooping hawk. And if he doesn’t hit hard enough to suit the NFL’s broken-nose lobby, he is still one of a very few players who can change a game all by himself. That he is also a brilliant and enthusiastic returner of punts means that all doubts regarding his courage are rendered moot because, if Sanders is reluctant to hit, he is clearly willing to be hit on what is arguably the most dangerous play in the game.

And yet—and there always is an “and yet” to this guy—as tight a rein as Sanders claims to have had on the Prime Time persona, it became his public definition. Baseball, for example, never got it, largely because baseball is the institutional equivalent of your Aunt Gertrude, who collects both balls of string and Winslow Homers in her attic because she never quite mastered the difference between that which is classical and that which is simply old.

“One thing about baseball is that the guys who have played a few years get to thinking they’re the authority on this and that,” Sanders explains. “They’re quick to throw their years in your face. Football isn’t like that, because I don’t care if you play ten, twelve years, a rookie will come in and knock your head off and you’re going to respect him, you know? That’s why I didn’t relate to that part of baseball.”

Baseball did not welcome Deion Sanders, whom it saw as a speedy dilettante who did not respect Our Game the way that Our Game respects itself. Baseball did not welcome Prime Time, whom it saw as a space alien. Sanders didn’t help himself, either. He got into an on-field wrangle with Carlton Fisk, which is rather like arguing socialism with the heads on Mount Rushmore. Once, after broadcaster Tim McCarver upbraided Sanders for playing a football game and a baseball game on the same day, Sanders responded by dumping a bucket of ice water on McCarver’s head. As promising a player as he was—in 1992, as an Atlanta Brave, Sanders hit .533 in his only World Series—baseball was not a context within which the subtle interplay between Deion and Prime Time would ever work.

In fact, by 1996 it had become clear that Sanders was losing control of the balancing act that had been his entire public life. He was a solid citizen by the standards of the Cowboys—which were hardly rigid—but his life was coming apart. His marriage dissolved swiftly and in rancid fashion. (Once, in court, when asked whether he’d committed adultery, Sanders replied, “Are you stating before the marriage of 1996 or after?”—which is pretty clearly not getting the point.) While he insists that it was the public that would not let his Prime Time persona go and that it was that ol’ devil media that kept the public hungry, Sanders was clearly dependent upon it himself. If it was a fabrication, then it had become real—a doppelgänger that Sanders was not secure enough to shake.

Today, he says the pressure was enough to make him contemplate suicide—most seriously three years ago in Cincinnati. That he did not follow through with it, he says, is because he heard the Word. And maybe he has. Of course, maybe he’s a heretic, too. Nobody—not even Carlton Fisk—ever called him that.

“If there’s a heaven, there’s got to be a hell, too,” he says. “Think on that.”

God, you’ve got to love sportswriting when it draws you into third-century theological disputes. Hey, Saint Athanasius, you da man!

Anyway, long about A.D. 200, a doctrine arose that held that the members of the Trinity were not three distinct personalities but only successive modes through which one God manifested himself. It became known as modalism and, later, Sabellianism, after Sabellius, an ancient Christian theologian who adopted the controversial doctrine as his own. Needless to say, this notion ran so contrary to the essential trinitarianism of Christianity—three persons in one God, and not one God acting through three successive agents—that all hell, you should pardon the expression, broke loose.

The Sabellians were given the gate from the early Christian church. The doctrine, however, was a stubborn one, persisting so durably into modern Pentecostalism that in 1916, it caused a split that divided the church into two distinct sects. It is now called the Oneness Doctrine, and it is the main problem that many modern Pentecostals say they have with Bishop T.D. Jakes, who, Deion says, brought him to the Word and the Word to him. Call him a modalist. Call him a Sabellian. Call him a heretic. Deion doesn’t care.

“He’s the only man I’ve ever called Daddy,” says Sanders, who never really knew his biological father.

Since coming to Dallas from West Virginia in 1996, Jakes has built an empire out of his Potter’s House church. His television show is one of the hottest on the television-preacher circuit, and his books sell in the millions. He drives a Mercedes and lives in a $1.7 million lakefront home next door to H.L. Hunt, and he is so wired into the world of Texas celebrity that he is likely to become the Billy Graham in a possible Bush Restoration. (Governor Dubya regularly uses Jakes in his outreach to minority communities.) Unlike many of his more judgmental colleagues, Jakes has involved himself conspicuously in ministering to battered women and gay people. There is nothing of the Christian bluenose to him. He is very much a man of this particular sinful world. Consider, for example, his views on the theology of satin sheets, taken from his book The Lady, Her Love, and Her Lord:

“You see, ladies, satin might be pretty, but it destroys all semblance of balance and leaves you grabbing for the bedpost and groping for handfuls of mattress just to turn around in the sack, much less try an acrobatic feat of passion.”

And, well, amen.

Sanders came to Jakes with his first wife, Carolyn, as they tried to rescue their marriage. Jakes was the perfect person to minister to Sanders. From the start, Jakes saw the effort that Sanders was making to reconcile the person he was with the person he’d created. “I found him to be, though outwardly a flamboyant person, inwardly very sincere,” Jakes says. “I was able to separate the character he plays on the field and who he really is.

“One thing I’ve not found him to be is somebody who says things he didn’t mean. When he wasn’t into it, he wasn’t into it, and everybody knew it. I have 50 percent of my church like that, and it’s wonderful, because they’ve learned not to be religiously fraudulent.”

It was Jakes who baptized Sanders in 1997 and Jakes who officiated when he and his new wife, Pilar Biggers, were married in the Bahamas two years later. Somewhere in there, for whatever reason, Deion made his peace with his own creation and, possibly, with everyone else’s, too. After all, the Father’s house has many rooms, and there are some nice ones down here, too, but you still have to live with yourself somewhere. If that’s heresy, he’s making the most of it.

The Potter’s House church is coming loose from the earth. The Wednesday-night Bible study is shaking the place. A camera on a crane swoops above the whole congregation like the Divine Eye as Deion Sanders comes bouncing down the aisle toward where I’m sitting. “Thanks,” he says, the gleam of righteous transport in his eye. “Thanks for coming.”

It is a huge and theatrical place, rows of pews rising in arcs and layers away from the pulpit. Two huge screens hang from the ceiling; a video of the service will be projected on them, as will whatever Bible verses Bishop Jakes chooses this night for his lesson. Deion flows easily into the enthusiastic congregation, one of many and nobody in particular. The band—pushed by an organ and a gorgeous bass guitar—reaches a long and sustained peak before the introductory prayers. There is a moment of soft and palpable anticipation before Bishop Jakes rises to speak—a gathering of the drama. Deion, who has been swaying to the music, goes still and silent. Worship falls on the place all at once.

Jakes dives into the Gospel of John, and he’s talking about how Jesus and the disciples went outside the camp to pray. “They said, ‘We don’t need your controversies and your factions and your de-nom-in-na-tions,’ ” he thunders. “And they went...outside the camp.”

“Preach, Daddy,” says Deion. He’s an enthusiastic celebrant, underlining his Scripture heavily and, when truly moved, waving his left arm in a huge flapping motion. They make the altar call, and a battalion of well-dressed deacons appears, each with a box of Kleenex in his hands, and people come down from all corners of the huge tabernacle. As the service winds up, we all join hands for the benediction, an old woman to my left, me, and Deion, and something feels as though it’s cutting the side of my hand, and I look down, and I realize that it’s the diamonds on his watch. At the end, he catches me in a sudden embrace.

“Welcome to my world,” he says.

And it is a whisper.

Charles P Pierce is the author of four books, most recently Idiot America, and has been a working journalist since 1976.