CUMMING, Ga. — When Durwood Snead moved to Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1989, he was struck by the lack of diversity in the region, just 30 miles north of Atlanta.

“It was a pretty much completely white county,” said Snead, who is white and was a pastor at the time.

According to the 1990 census, of the 44,083 people who lived in Forsyth County, 43,573 were white (close to 99%) and just 14 were Black.

It was a place, Snead said, where generations of families typically lived their entire lives. It was also a place with a deep and complex history of racial violence.

In 1912, a small population of Black residents, dozens of whom were land and business owners, were violently expelled from the county, their livelihoods stripped from them. Three Black men were lynched and the remaining Black residents were ordered to leave and told never to return.

For many Black Georgians, even those unaware of the details of that incident, it’s universally understood to generally avoid the county.

“The history of Forsyth County is literally a case study of racism in American history,” said Nafeesa H. Muhammad, an associate professor of history at Spelman College in Atlanta. “The fact that most Black people do not know about Forsyth’s history or are told to stay away, ironically perpetuates social segregation and delays rectification.”

More than a century later, one-third of Forsyth’s residents are nonwhite, but less than 5% of the county is Black, a figure that’s been stagnant for decades. Yet the numbers alone, some residents say, don’t tell the full story of present-day Forsyth County.

A key chapter in that story is an attempt by Snead and a group of pastors to reshape the county’s history by establishing a college scholarship program in 2022 for descendants of Black families who were violently expelled 110 years before.

The founders are clear that the scholarships are not reparations, a word many in the community would consider divisive, but instead “an act of love,” an acknowledgement of past harms in the hope of fostering a positive path forward.

Forsyth’s days of racial terror

In 1912, Forsyth County was home to about 12,000 residents, including 1,098 Black people scattered throughout the county. But that September, an 18-year-old white woman named Mae Crow was brutally assaulted, bloodied and left unconscious in a wooded area. She eventually died from her injuries and three young Black men — the only Black people in that part of the county at the time — were accused of killing her, with little evidence other than a coerced confession from one of them.

One of the men, 24-year-old Rob Edwards, was arrested and jailed only to be dragged from his cell the following day by a mob of angry white residents. He was allegedly hitched to the back of a wagon with a noose around his neck, driven to the downtown square in Cumming and hung from a telephone pole as onlookers took turns riddling his lifeless body with bullets. Two Black teens, Ernest Knox, 16, and Oscar Daniel, 18, were also hanged after one-day trials.

The other Black residents of the county were threatened with death if they did not leave as night riders posted letters warning of the impending terror. Within three weeks, the Black population in Forsyth ceased to exist. Many were forced to leave everything they had worked hard to attain behind without anything in return.

Still, racial animus and violence was not confined to 1912, as residents enforced its ban on Black residents. A group of Black children and their counselors went camping at Lake Lanier in Forsyth in 1968. After sundown, a group of white men reportedly surrounded them, yelling racial slurs until they left. In 1980, a Black firefighter was shot in the head after nightfall by two white men while attending a company picnic.

Much of this history was buried in newspaper clippings until a civil rights march was met by a Ku Klux Klan march in 1987. Oprah Winfrey brought national attention to the area that year, highlighting the county where “no Black person had lived for 75 years.” In 2016, author Patrick Phillips, a former county resident, published “Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America,” which chronicled the 1912 expulsion and how, despite thousands of witnesses to the lynchings of the three men, no one was ever held accountable for their deaths.

Because of this, Phillips said he believes the harm has never truly ended.

“The effects of the 1912 expulsions are not over, not buried in the past, but ongoing, as African American descendants continue to lose out on all that suburban wealth generation, and as the perpetrators’ descendants continue to profit from it,” he said.

Change in Forsyth

Since Winfrey came to Forsyth, change has been slow but steady, according to Snead. Population growth over the last 30 years has introduced Asian and Hispanic Americans to the region — as well as new cuisines and customs. Snead said this shift has allowed a marked shift in mindsets on how to talk about the past.

“I’m encouraged by how many people are really embracing the discussion and realizing that truth is a good thing,” he said, while acknowledging that not everyone is ready for change in the same way.

“We all want to live in peace and prosperity, for our children to have a better life and live in safety … but people have different ideas of how you get to that,” he said.

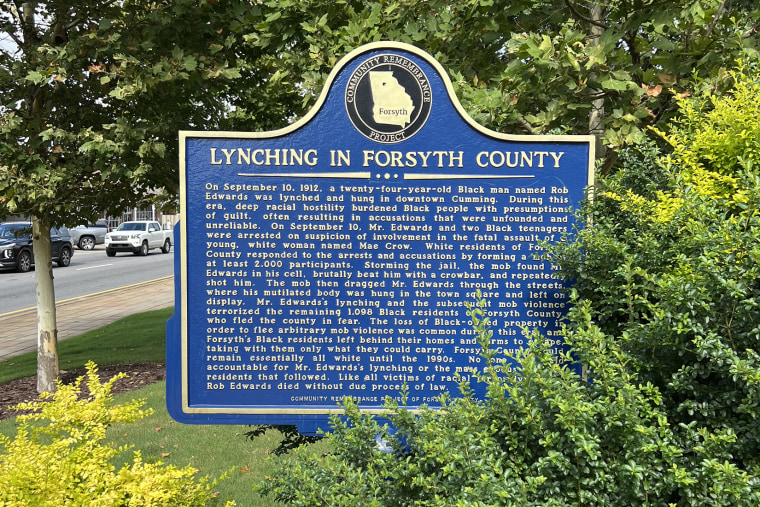

A historical marker, erected in 2021, now sits in downtown Cumming where Edwards was hanged, acknowledging what took place there over a century ago. A new elementary school, named New Hope, opened up in 2022, honoring more than a dozen former African American schools in the region. A group of volunteers restored Tolbert Street Cemetery, the site of an African American burial ground and Methodist church established in 1871.

Phillips sees these developments as “laudable steps” toward progress. Still, he says, more can be done.

“There is still much that has been left undone, like teaching the county’s real history to local students, and making sure that the next generation of Forsyth residents understand what once happened in the place they call home,” he said. “But above all, there has been no formal public apology and no attempt to repair the economic harm done to those families whose fortunes were forever changed in 1912.”

K-12 students across Georgia learn state and local history, but there is no explicit mention of the 1912 expulsion on Forsyth’s education website. A spokesperson for the school district did say, however, that students have access to local resources about the expulsion.

Josh Byrd, whose own family was part of the expulsion, moved to Forsyth six years ago, much to the chagrin of friends and family, who warned him about the county’s fraught history.

“There is a change that is taking place,” he said, adding “it’s not the Forsyth you’ve heard of.”

Choosing to form his own opinion about Forsyth today, Byrd opened a barbershop in the county two years ago. Speaking at this year’s scholarship event, Byrd has now become a de facto ambassador, encouraging other descendants to move back and change the narrative.

“I had to ultimately make a decision here,” he said. “Am I going to operate in fear or am I going to trust the word of people that I trust that are saying, ‘Hey, man, this is different.’”

Snead acknowledges that decades of injustice won’t be reversed in a few years, but doing something, he says, is better than doing nothing at all.

“This is not fixing anything. This is not justice,” he said.

“A bigger vision I have is for the county that was called the most racist in America in 1987, the dream is for it to be called the county that’s known all over the world as the county of love.”

Recipients of the scholarship, who are required to write essays, remain in good academic standing and prove they are direct descendants of someone expelled from the county, receive up to $10,000 a year for up to four years of undergraduate studies.

To date, there have been 14 recipients. Six 2024 awardees and eight continuing scholars were recognized at a scholarship luncheon at a Brownbridge Church in Cumming in July. Since its inception, more than $285,000 in scholarships have been distributed through more than 150 donors, Snead announced at the event.

Erin Hall, a junior at the University of Georgia and a recipient, said earning the award has been both personally educational and conflicting. She learned that she had a great-great-grandfather who was a sharecropper in Forsyth County before he was separated from his parents and siblings as a teen, likely because of the expulsion.

“It was great to know that I could benefit from it,” she said of the scholarship, “but I also question if I even deserve this for how hard they worked towards everything.” She said she just wants to “make them proud.”

For more from NBC BLK, sign up for our weekly newsletter.