Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Uploaded by

Ian GeikeCopyright:

Available Formats

Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Uploaded by

Ian GeikeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Dance and Place Body Weather Globalisation and Aot

Uploaded by

Ian GeikeCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/276080786

Dance and Place: Body Weather, globalisation and Aotearoa

Article · March 2015

DOI: 10.15663/dra.v3i1.32

CITATION READS

1 39

1 author:

Miriam Marler

University of Otago

1 PUBLICATION 1 CITATION

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Miriam Marler on 24 July 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Dance and place: – Marler 28

Dance and place: Body Weather, globalisation and

Aotearoa

Miriam Marler

Independent Researcher

Abstract

This article will explore the relationship between dance and place. Using the work of

Body Weather (BW) practitioners such as Snow (2006), Grant & de Quincey (2006),

and Taylor (2010), this article will explore their unique viewpoints and somatic

approaches to engaging with place. Also the works of other scholars and movement

practitioners will be used to investigate how place shapes dance practices

(Alexeyeff, 2009; Brown, 1997; Gray, 2010; Mazer, 2007; Savigliano, 2009). BW

threads within the Aotearoa/New Zealand contemporary dance scene will be traced,

culminating in suggestions about the implications for practicing BW in an Aotearoa

context. How understandings of movement can emerge from different environments

is the focus of the research.

A dancer in essence is an anonymous lightning, a medium of the

place. That is how I want to be … an attempt to discover and

initiate dance in all places. (Min Tanaka, founder of Body Weather

as cited in Grant & de Quincey, 2006, p. 252)

Introduction: What is Body Weather?

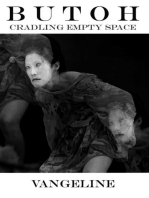

Body Weather (BW) is a movement practice and philosophy that was developed by

Japanese avant-garde dance-artist Min Tanaka in Tokyo in the late 1970’s (Snow,

2002). The approach developed from butoh, a Japanese philosophy and

performance practice generally accredited to Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno.

BW grew out of Tanaka’s ‘laboratories’/workshops with groups of international

dance and art practitioners, many of whom were part of Tanaka’s performance

company Maijuku. Tanaka and the company began working in the rural village of

Hakushu, Yamanashi, two and a half hours northwest of Tokyo in the early 1980's;

the laboratories’ focus was to engage in intensive body-based investigation of the

land (Venu, 2006). These investigations happened through long hours of manual

work on the organic farm; intensive training through the movement system known

as “M/B” or “M&B” (which stands for Mind/Body, Muscle/Bone or Music/Body, all

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

29 Dance and place: – Marler

and any of which can be used); and “groundwork” which consisted of hands-on

partner bodywork or “manipulations” and sensory/image-based investigations,

often done outdoors.

Tanaka himself has been involved in many performances both in traditional

theatre venues and in outdoor, site-specific environments both in Japan and

internationally, and has collaborated on many occasions with artists from other

disciplines (MoMA PS1, 2012; Venu, 2006). Since its beginnings, BW has been

globalised in two ways. The first is that it has been transferred to other

geographical locations to be investigated in different cultural contexts, and

secondly what is actually practiced has changed. Dancers such as Stuart Lynch,

Tess de Quincey, Frank Van de Ven and Oguri, some of whom worked with Tanaka

in Maijuku, now practise and lead their own investigations in Australia, Europe and

the US, often travelling internationally for performance or workshops (Body

Weather, n.d). Other artists use BW as a springboard for creative work in different

disciplines.

Due to this relocating of the Japanese-born dance practice, challenges in

translation or re-contextualisation are evident. Thus, the practice of BW shifts

uniquely depending on where it is practiced and with whom. In order to understand

BW in relation to place, we must first contextualise it within the broader world of

dance to see how globalisation affects other dance forms and communities. By

looking at the meanings of ‘World Dance’, we may form a notion of how dance-

meanings shift according to place and how dance shapes place.

Dancing globally and in local places

The relatively new term ‘World Dance’ is now being used in dance studies to

encompass a variety of dance-forms and practices. Worldwide, dances happen in

different yet specific places where dance is either still rooted to its cultural

context, or has changed through innovation. ‘World Dance’ breaks down and re-

frames what ‘dance’ is, opening up new territory and broadening the conceptual

framework of how we see dance.

Savigliano (2009) argues for a re-thinking of the umbrella term ‘World Dance’

and asks how choreography (a Western notion) can be used as “a processor of

differences” (Savigliano, 2009, p. 175). She suggests that different cultures of

dance can come together to engage in dialogue. In the territory of globalisation,

we must be open to multiplicity, processes of translation, and tailoring or

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 30

reframing of dance. She says dancers need to enter into intercultural dialogue with

producers, scholars, critics, students, or with other dancers (Savigliano, 2009).

Foster (2009) denotes ‘World Dance’ as a term which “intimates a neutral

comparative field wherein all dances are products of equally important,

wonderfully diverse, equivalently powerful cultures” (Foster, p. 2). However, this

is not true. We see this through Foster’s tracings of the lineage of dance histories

from a critical viewpoint. She states that there are politics of power implicated in

researching dance that need to be acknowledged and questioned, both in past

research and in present studies.

Together, Foster (2009) and Savigliano (2009) question how ‘World Dance’

might replace ‘dance’. They seek to expand ‘dance’, and ask us to consider new

and alternative definitions of choreography, technique, a dancer, and

performance-presentation. They highlight the differences in power between dance

that falls within the frame, and dance in “wild” places outside of it: “out there in

the world” (Savigliano, p. 163). Both affirm “the need for new models of history

writing that could provide alternative narrative structures” (Foster, p. 3). They

suggest that communities that have not been written into history, such as

indigenous people, need to be given voice.

For example, in the Cook Islands, globalisation of their dance “engage[s]

local identities with global processes” (Alexeyeff, 2009, p. 1). Alexeyeff (2009)

shows how Cook Islands dancers are affected by changes in tourism and

commodification, by funding and other support (or lack of it), by European

invasion, and the introduction of Christianity. These changes in politics can be seen

through looking at Cook Islands expressive dance practice as well as individual,

local and national identities.

‘Worlding’ dance sees dance not as separate from culture, ‘cultureless’, and

not as a cultural ‘mirror’ or reflection of society, but as the actual production of

culture. Dance can be seen as a way of crafting identity and as a generator of

cultures within and outside of itself. Simultaneously, dance is affected by political,

cultural, social and economic constraints. Constraints of political, cultural, social

and the economic are illustrated in Alexeyeff’s study on Cook Islands dance (2009).

She illustrates how one community is in fact a microcosm of globalisation. Notions

of belonging, identity and place are implicated in global changes, forming new

concepts of belonging and ‘place’ within dance studies (Alexeyeff, 2009; Foster,

2009; Savigliano, 2009).

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

31 Dance and place: – Marler

Being in Aotearoa/New Zealand

Take for instance Aotearoa/New Zealand which is called a bicultural context.

Although we are in an era of ‘post-colonisation’, issues of colonisation still need to

be addressed. Mazer (2007), discusses the Māori dance company Atamirai in their

performance Ngai Tahu 32, choreographed by founding member Louise Potiki

Bryant. Mazer describes the Māori dancers’ bodies as “implicitly come to reveal

and embody the effects of colonisation: ritual dance suppressed by the aesthetic”

(Mazer, 2007, p. 291). She implies that we can see the effects of colonisation on

the dancers’ moving bodies. We are able to see the effects of colonisation

embodied through the power-play between more traditional Māori practices and

the Western aesthetic of contemporary dance. Mazer suggests that this kind of

“working between cultural forms” (p. 291) is powerful in that it highlights

problematic issues of biculturalism in our wider New Zealand society.

Jack Gray, (2010), another founding member of Atamira Dance Company,

reflects on his experience at ‘Indigenous Dance Laboratory 2’ in Broome, Australia.

As a Māori choreographer/dancer he describes the Australian environment as an

integral and awe-inspiring part of his trip. “We were privileged to be in this

unbelievable Dreamtime landscape of ochre red dust, rock, green Indian Ocean,

the crispest blue skies, the abundance of life … all had an incredible impact on

me” (p. 3). Gray experienced the location through his body in everyday situations.

He also experienced cultural identities embedded in the movement learnt from

Indonesian choreographer Jecko Siompo and Congolese-born Andréya Ouamba

(Gray, 2010).

How the body is situated and accommodates environment, local flora and

fauna, is felt on a somatic level. Both Gray (2010), and Mazer (2007), highlight a

Māori worldview wherein embodiment is integral to experiencing the world. Place

is understood through the body. Mazer says, “From a Māori perspective, to locate

one’s whakapapa [genealogy] in a file is not quite the same as recalling it from the

land itself” (2007, p. 291, [emphasis added]). Thus both the land and the body

hold pertinent cultural knowledge.

Brown (1997) reflects about dis-connection to land. As a Pākehā

choreographer/dancer she discusses issues of cultural translation when working,

dancing and transferring choreographic work between Britain and New Zealand.

She is both an expatriate in England and a “visitor” in Aotearoa, thus dwelling in a

place of “in-between-ness” (p. 140). Brown points out that unlike indigenous

Māori, the Pākehā (New Zealand European) do not belong to the land. She says

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 32

“though the Māori are tangata whenua (of the land), the Pākehā as Manuhiri

(visitor) is not” (p. 140). She links her cultural identity to the feeling of not

connecting to any place, saying “the Pākehā belongs, in a foundational sense,

neither here nor there” (p. 140).

As a Pākehā-born New Zealander, Brown’s reflections resonate with my own

identity. I have one English-born parent and one Australian-born and grew up in a

small community in Dunedin comprising predominantly of European New

Zealanders. I too feel culturally nomadic or dislodged from belonging to any one

place, yet Ōtepoti/Dunedin is also my home. I have an awareness of the

problematic way the British have engaged historically with the New Zealand’s land

and people, and too have an admiration for indigenous Māori values and their

“determination” (Brown, 1997, p. 140). As a student researching dance in the

world, I feel the need to engage my own identity respectfully with the environment

and Body Weather is my starting point for this investigation.

‘Dancing a place’ with Body Weather

For Australian scholar and performer Peter Snow (2006), collaborations in BW

began with Amsterdam-based dancer Frank Van de Ven. The two met at a BW

laboratory with Tanaka, and their performance series Thought/Action is about

improvising through thought, or speech, and through action or dance. Their work

explores the interception of these two modes of improvisation, as well as how the

identities of the two performers relate. Together they investigate “places as a

mode of being in performance” (p. 228), rather than place being used as a frame,

provocation, or performance itself. Snow discusses the embodiment of place

through three elements of improvisation—“observation”, “reflexivity” and

“becoming”—a triad of “interweaving processes” (p. 235). He says, “If beings are

implaced, then they are always in some kind of site, always in situ, but in situ is a

developing mode. In performance especially, bodies are remaking themselves,

being made and remade, all the time” (p. 235). These artists focus on and utilise

their constantly changing embodied experience for improvisation impetus,

determining relationship to one another and the performance process.

Another Australian, site-based performer Gretel Taylor (2010), discusses the

key concept of ‘emptiness’ in BW training. The process involves emptying the ‘self’

of habits and societal constructs so that a dancer may invite things from the

‘outside’ in. She suggests this enhances the dancer’s body and mind to be

receptive to the environment around (Taylor, pp. 77–79). However, Taylor argues

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

33 Dance and place: – Marler

that to ‘empty’ the body is both an impossible and inappropriate concept for her as

a non-indigenous site-specific dancer in the post-colonial Australian context. She

says “emptiness has been a false premise underscoring dispossession and genocide”

(p. 85). She describes how British colonisers came to Australia and saw an ‘empty’,

un-inhabited land. In reality, there were in fact indigenous Aboriginal people living

there. Taylor suggests that these communities were not acknowledged because

they did not fit into the British framework of what it means to dwell within a

landscape. What followed was a denial of indigenous Aboriginal existence (Taylor,

2010).

Taylor also argues that while BW strives to deconstruct the body of its social

inscriptions, it de-genders and de-culturalises the body. Taylor writes, “aspiring

neutrality or emptiness”, are problematic in that skin colour and sex are

undeniable inscriptions on the body (p. 80). Questioning these assumptions in BW,

Taylor seeks to find an alternative vocabulary and practice in relation to dancing in

the land she lives. Using feminist theory as a framework, she introduces the idea of

bringing her “whole self/body to meet with the Australian site” (p. 86), neither

land nor dancer being at the forefront of the dance, but both becoming fully

present, engaging in an encounter that is relational—both bringing their histories

and identities in full to the conversation—and not erasing or emptying any part of

place or dancing self. Taylor uses what she calls “locating” (p. 73) to do this—a

practice whereby she locates herself through listening to/noticing the nuances in

the environment that she is in, and responds accordingly, dancing from a

“permeable” (p. 85) body.

Similarly, Grant and de Quincy (2006) discuss BW in relationship to the

Australian landscape and its indigenous peoples. The authors ruminate as non-

indigenous artists working with the land, asking: “How do I stand in Australia?” (p.

248), and how to relate to the realities of biculturalism in this era of post-

colonialism. Grant says “I am not entirely comfortable with the knowledge that the

prosperity which I now enjoy is built on a foundation of theft and murder” (p. 266),

and discusses the meaning of dwelling, stating that ethically it must be constantly

revisited due to the ghosts of his past colonising ancestors.

As part of their investigation into these issues, Grant & de Quincey (2006)

discuss their research which has taken place through BW practices. Their projects

include Triple Alice 1, 2 and 3 (1999–2001), described as laboratories in the

Australian Central Desert. They engaged with the landscape by first researching its

history and significance to local Aboriginal communities. Grant concludes

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 34

Aboriginal philosophy specific for this area “remained largely hidden and silent” (in

Grant & de Quincey, 2006, p. 254). Perhaps he highlights a lack of understanding

with the indigenous Australian population; or perhaps it was inappropriate for them

to share this knowledge. Grant & de Quincey’s dance research in the desert

involved what is called “omnicentral Imaging” in which dancers take on “images”

from the surroundings (p. 250). They suggest that the body may transform through

this practice, and become a site for performance (p. 250). De Quincey talks of

places entering and inhabiting people and the relationships between dancer and

site. Grant places their work apart from other site-based performance, stating

that,

… in Body Weather place performs bodies as much as bodies are in

place. And so the hidden workings of an ever present dimension of

experience—the ways in which the places we inhibit makes us who we

are—is revealed and laid open. (Grant & de Quincey, 2006, pp. 267–268)

Therefore BW practice for both Grant & de Quincy (2006) and Taylor (2010)

can be seen as a method for understanding their own culturally situated identities.

They weave values that support the Aboriginal community into their work, and try

to understand the enormity of experiences held within the places they live and

dance in. Grant & de Quincy discuss ‘imaging’ as part of their practice—a method

for embodying simultaneous multiple sensibilities of the environment to generate

movement. Like Taylor, they talk of the body as “becoming a vessel”, speak of

“rhythms taken on from outside”, and having “cellular reactions” to the site they

inhabit (p. 251). Describing the experience, Grant narrates the path of the BW

dancer, who is:

All the time, mapping, measuring, naming, finding sense, analysing

elements of the place … with time, abiding in the dwelling with

sustained attunement, she finds the place in her body, her body is in

the place. The place leaves its footprints, its residues, in her flesh,

vibrates her, making her something else. Someone she wasn’t. (Grant &

de Quincy, 2006, p. 256)

Snow (2006), on the other hand discusses his relation to place as more

transitory. He improvises in different places around the globe and does not appear

to engage in post-colonial discourse. Like Taylor (2010), Grant & de Quincey

(2006), he too is ‘mapping' and 'finding sense’, yet his sense of place is about

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

35 Dance and place: – Marler

improvising identity. He discusses the paradox that places can be both fleeting and

enduring. He suggests place can be held in the body momentarily, or be revisited

through memories, time and time again (Snow, 2006, pp. 228, 246).

All three articles speak of somatic transformations in the body. They share a

view that place affects identity in BW dance practice. Van de Ven and Snow (2006)

seek to depart from their own inscribed identities in order to “displace” (p. 228)

one another when performing. They seek to work from a “transparent” (Van de

Ven & Snow, 2012) or ‘neutral’ body. This departure from the individual self is

closer to Tanaka’s description at the beginning of this article of a dancer being

“anonymous” and a “medium of the place” (Grant & de Quincey, 2006, p. 252). On

the other hand Taylor and Grant & de Quincey seek to dance in a place without

negating any part of the self. They acknowledge their inscribed cultural identity.

As we saw above, Taylor has found new culturally appropriate structures through

which to frame her dance practice.

Body Weather in Aotearoa/New Zealand, implications and

conclusions

The above literature provides a picture of dance from BW practitioners wherein BW

has its own parameters for conceptualising choreography and embodying place. It

can be seen as a type of structured-improvisation where a relationship between

place and the dancer’s body may be explored. Somatic experience is honed in on;

the senses are used to investigate qualities and details of a specific environment.

Memory, sensation, and image are used to explore situated identities and deepen

connection with landscape and its significance. The sensation of an insect on the

forehead on a hot day might be investigated for its potential to inform movement

or state in the body; or the rhythm of the water felt while standing in a river might

be remembered kinaesthetically and drawn on to later in the studio. Choreography

might be a structuring of such “images”, enabling a dancer to move through

different corporeal experiences, resulting in a kind of dance or performance. Here,

movement is not fixed or ‘set’, but like other improvisational approaches the

dancer must always be alert to moment-to-moment somatic changes and

movement choices.

Additionally, practitioners drawing on BW are engaging in discourses of place

and cultural identity, especially in Australian contexts where postcolonial

conversations are currently pertinent. Such artists are looking at how local places

and cultural identities intercept with BW in today’s global climate and BW

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 36

techniques and assumptions are being critiqued for relevancy. The literature

signals how this Japanese-born dance is changing in new globalised contexts. As

suggested above, landscape holds different meanings depending on worldview.

In Aotearoa/NZ there are a significant number of dance-artists influenced by

BW or butoh, yet little is written about this history. A search for “butoh” on the

Dance Aotearoa New Zealand (DANZ) website recently found fifteen mentions of

the practice, yet I have only been able to find three scholarly documents about

butoh alone in the Aotearoa/Pacific region. These are: Miki Seifert’s (2011)

doctoral dissertation, William Franco’s (2008) master’s thesis, and Bert Van Dijk’s

(2011) article. In terms of BW, Becca Wood's (2010) master's dissertation briefly

cites Min Tanaka as an influence on her practice. In addition, renowned butoh

scholar Sondra Fraleigh (2010) only notes two artists of the global butoh movement

in Aotearoa/NZ: Lemi Ponifasio of MAU dance-theatre and Wilhemeena Monroe of

SOUL Centre (p. 31), both are based in West Auckland. As the director and

choreographer of MAU, Ponifasio accredits finding his own way in performanceii to

Min Tanaka, after turning away from conventional contemporary dance techniques

(Manson, 2000). However, the Samoan-born artist does not see himself as a butoh

dancer (Jahn-Werner, 2008), and believes “butoh encompasses many, many

different performers all with different styles, techniques and staging. It means

different things to different people” (Meredith, n.d., para. 4). Monroe has worked

with Ponifasio in the past and is also influenced by Tanaka, among other butoh

notables (Fraleigh, 2010). She fuses butoh with somatic education and

contemporary dance in her choreographic work and through her somatic research

centre (Fraleigh, 2010).

However, in addition to those mentioned, there are a significant number of

other contemporary dancers in Aotearoa/NZ influenced by BW or butoh in various

ways. Charles Koroneho, Lynne Pringle, and Michael Parmenter are three such

practitioners, each a notable artistic and educational presence in the Aotearoa

Contemporary Dance scene. Koroneho “explore[s] cultural collaboration,

intercultural performance and the intersection between choreography,

performance art and theatre” (Koroneho, 2011, para. 2). His artistic research,

under the conceptual platform Te Toki Haruru, investigates “the collision between

maori [sic] cosmology, New Zealand society and global cultures” (Koroneho, 2011,

para. 2). He “draw[s] from Dance, Body Weather and Performance Art” to explore

an indigenous approach to choreography and performance (Smith, 2012).

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

37 Dance and place: – Marler

Pringle is “deeply committed to the development of the performing arts in

New Zealand” (Bipeds Productions, 2005, para. 1). Her BW knowledge was gained

by working with Parmenter and through her study with Tanaka in New York (Bipeds

Productions, 2005; personal communication, July 5, 2013). Parmenter is also

influenced by Tanaka’s BW Laboratory, melding it with Hawkins Technique, and

American “new dance” methods such as Klein and Alexander techniques, Contact

Improvisation, and Ideokinesis (IndependANCE, 2011b). Alyx Duncan, Dave Hall,

Joshua Rutter, Elle Louise August, Tru Paraha, and myself all trained with Min

Tanaka in Japan, and have since worked in various performance trajectories.

Others, such as Kristian Larsen have worked with Tanaka in Aotearoa when the

artist presented work in Auckland and Wellington in 2000 (Chesterman, 2014;

Larsen, n.d.).

MB has been a popular training approach for professional performers and

body-based practitioners in Auckland where regular classes run through

IndependANCE. Tutors such as Kerryn McMurdo, Becca Wood, Geoff Gilson, Charles

Koroneho, Michael Parmenter, and Joshua Rutter lead these sessions

(IndependANCE, 2011a). Christchurch’s recently established Re:Map classes

developed by Erica Viedma, Julia Harvey and Paul Young also offer MB classes

(South Island Dance Network, 2012), as does the new GASP! Dance Collective in

Ōtepoti/Dunedin.

Although this is not an exhaustive list of BW threads in Aotearoa’s

contemporary dance scene, it does signal part of the extent to which contemporary

dancers, choreographers, and educators in this country might be indirectly or

directly influenced by the Japanese-born practice and philosophy of BW and its

parent butoh. The themes that arise through this brief survey of BW and butoh

influences in Aotearoa are: the incorporation of indigenous approaches to the body

and movement; the need for experimentation and the extension of contemporary

dance boundaries; and discourses of environment, landscape, and belonging.

However further research and articulation of BW and butoh threads in NZ dance-

cultures, preferably by practitioners themselves, would shed light on the nuances

and intentions of these practices. As Maufort (2007) importantly notes, the

performing arts scene in this country is prolific yet under represented in

scholarship. Documenting more of the cultural practices such as BW that influence

our dance-making would engage Aotearoa/NZ more actively in global dance

debates, and articulating cultural knowledge practiced acknowledges and pays

respect to the lineage of teachers gone before us.

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 38

Towards embodying Ōtepoti

My own current practice in Ōtepoti/Dunedin draws from training with Min Tanaka

in Japan; an undertaking inspired by Aotearoa contemporary dance teachers

Charles Koroneho, Wilhemeena Monroe, and Michael Parmenter. iii Travelling to

Japan to live, work, and study BW and butoh forced me to face my cultural

assumptions, particularly about the body, movement, and dance. Seven years later

I question how elements of BW might relate to my cultural context and local

landscape back in Aotearoa. As a Pākehā dancer-researcher I seek appropriate

parameters for working in the bicultural Aotearoa/New Zealand environment. As

the above literature signals, dance in Aotearoa responds to specific parameters

wherein issues of belonging, identity, and landscape are pertinent and interwoven

within the political, social, and cultural landscape. The somatic implications for

dance in Aotearoa are about engaging with natural phenomena as a way of

identifying with the landscape and understanding how we belong here as dancers

and as human beings. Therefore dancing in Aotearoa engages me in a personal re-

questioning of my assumptions about dance, my identity, and the landscape in

which I live.

The following somatic portrait of dancing in Aramoana, a beach near my

hometown of Ōtepoti/Dunedin in the South Island, provides an example of how my

BW-inspired practice is a way of revealing connections and disconnections to self

and homeland. My interest lies in how I might strengthen my relationship with the

landscape by exploring and delighting in the Aramoana environment along the man-

made mole. Through somatic movement investigation I pondered how my dance

might transform as I engaged with plant, animal, land, sky, and water. My

intention was to connect somatically, allowing movement responses to arise in

relation to the elements along the length of the mole.

When I was standing in the water or crawling over the rocks, I felt like I was

listening to a harsh landscape. Somehow, I was aware that this land was so

familiar and comforting - I had grown up playing here and it felt ingrained in

my body - yet paradoxically it also felt hard and unforgiving. Something was

uncomfortable about being out there by the water early in the morning. My

connection felt somewhat forced or tense. I wanted to let go of any

judgments and hear the land speak for itself. I attempted to soften my body

and listen to the rhythms of the place. I honed my senses on the presence

around me. (Marler, 2014, p.13)

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

39 Dance and place: – Marler

By consciously drawing on proprioceptive, tactile, aural, visual, and kinaesthetic

information I was able to focus on the detailed rhythms, markers, patterns, and

chatterings of the place (Marler, 2014). I chose the rocks, water, gulls, and the

open space at the end of the mole to engage with for my exploration. I traced

patterns of white dung on brown stone with all fours pressed to the sharp surfaces;

I sensed the rhythm of waves seep into my pelvis and spine, a quiet yet powerful

guiding force; the chaotic cries and the flurry of feathered gulls in flight shifted me

to fling my arms up like the birds' wings while my feet stomped the clay as if in

celebration or protest; and the expansive horizon where water and sky met calmed

me to subtly lilt my torso, neck, and chest. After several hours of practice, my

sense of self had shifted and expanded. I felt more at ease in my self and in the

place, as if I had lessened a gap between myself and the landscape (Marler, 2014).

This brief somatic portrait has roots in Tanaka's BW work while

simultaneously unearthing an uncertain relationship to the Aotearoa landscape. As

Brown (1997) suggested earlier, being Pākehā can reveal tensions of belonging

which are no doubt due to a history of colonisation. Herron Smith (2010) similarly

notes that Pākehā identity engages “the pull between connections and

displacement” (p. 68), a pertinent paradox given our current global and

postcolonial climate. The author further elicits that in other Aotearoa performance

contextsiv, Pākehā identity is frequently expressed by employing elements of the

landscape as sources of inspiration, by reflecting on ancestry from elsewhere, and

by forming relationship with Māori (Herron Smith, 2010). Therefore, like Grant &

de Quincey (2006), and Taylor (2010) earlier, my practice can be seen as a method

for understanding my situated identity as Pākehā New Zealander and deepening

sensitivity to the social, cultural, and geographical landscapes that I am part of.

What I have found is that this practice has given me a deeper sense of home

in my body and in the landscape in which I was born. It has provided me insights

into my own genealogy or whakapapa which is rooted elsewhere, yet the process

has also inspired my attention to Māori perspectives of land, body, and identity. As

Māori scholar Hinari Moko Mead (2003) states, land is not considered an asset

belonging to people, but it is people that belong to the landscape. It is about

“bonding to the land and having a place upon which one’s feet can be placed with

confidence” (Mead, 2003, pp. 272–273). More dialogue with local Ngai Tahu (the

local tribe) communities would be one way of deepening this research and my own

understandings of the local landscape and its significance to Māori.

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

Dance and place: – Marler 40

My own identity and dance genealogy illustrate the importance of global to

local contexts and processes within and outside of dance. My practice, like the

work of Taylor (2010), and Grant & de Quincey (2006), does bring implications of

colonial power imbalances that need to be questioned thoughtfully. Dancing BW

implicates me as a Pākehā dancer not only in the transplantation of practice here,

but also in the reconfiguration of this knowledge in terms of our socio-cultural

landscape. This means a process of making sense of BW within the situated

implications, and a questioning of how BW might meet indigenous perspectives of

landscape, dance, and body. Cruz Banks (2011) aptly points out that dance can be

a powerful way of “strengthening [our] connection[s] to home, land and sea” (p.

82).

References

Alexeyeff, K. (2009). On the beach: An introduction. In K. Alexeyeff (Ed.), Dancing from

the heart: Movement, gender, and Cook Islands globalisation (pp. 1-28). Honolulu,

Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

Bipeds Productions. (2005). Lyne Pringle. Retrieved from http://www.bipeds.co.nz/lyne.html

Body Weather. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.bodyweather.net/

Brown, C. (1997). Dancing between hemispheres. In L. Stanley (Ed.), Knowing feminisms:

On academic borders, territories and tribes (pp. 133-134). London, England: Sage.

Chesterman, M. (2014). Min Tanaka (Dance Theatre). Retrieved from

http://www.marcchesterman.net/min.html

Cruz Banks, O. (2011). Dancing te moana: Interdisciplinarity in Oceania. Brolga, 35, 75-83.

Foster, S. L. (2009). Worlding dance: An introduction. In S. L. Foster, Worlding dance (pp.

1-13). Basingstoke, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fraleigh, S. (2010). Butoh: Metamorphic dance and global alchemy. Urbana, IL: University

of Illinois Press.

Franco, W. (2008). Cross-cultural collaboration in New Zealand: A Chicano in kiwi land.

(Masters thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand). Retrieved from

http://muir.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/878/02whole.pdf?sequence=2

Grant, S., & de Quincey, T. (2006). How to stand in Australia? In G. McAuley (Ed.), Unstable

ground: Performance and politics of place (pp. 247-271). Brussels, Belgium: P.I.E

Peter Lang.

Gray, J. (Winter 2010). Broome: International indigenous dance laboratory 2. DANZ

Quarterly, 20, 3.

Herron Smith, A. A. (2010). Seeing ourselves on stage: Revealing ideas about Pākehā

cultural identity through theatrical performance. (Unpublished doctoral thesis).

University of Otago. Dunedin, New Zealand.

IndependANCE. (2011a). Classes. Retrieved from

http://www.independancenz.org/classes.html

IndependANCE. (2011b). Michael Parmenter. Retrieved from

http://www.independancenz.org/michael-‐parmenter.html

Jahn-Werner, T. (2008). Dance: The illustrated history of dance in New Zealand. Auckland,

New Zealand: Random House.

Koroneho, C. (2011). Koroneho. Retrieved from

http://www.tetokiharuru.com/koroneho.html

Larsen, K. (n.d.). CV. Retrieved from

http://throwdisposablechoreography.blogspot.co.nz/p/blog-page_21.html

Manson, B. (2000, July 13). Ponifasio dancing the dance: [2 edition]. Dominion, p. 18.

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

41 Dance and place: – Marler

Marler, M.C.M. (2014). (Re) Conceptualising dance: Moving towards embodying environment

form Japan to Aotearoa (unpublished masters thesis). University of Otago, New

Zealand.

Maufort, M. (2007). Performing Aotearoa in an age of transition. In M. Maufort (Ed.),

Performing Aotearoa: New Zealand theatre and drama in an age of transition (pp.

13–16). Brussels, Belgium: P.I.E. Peter Lang.

Mazer, S. (2007). Atamira dance collective: Dancing in the footsteps of the ancestors. In M.

Maufort, & D. O'Donnell (Eds.), Performing Aotearoa: New Zealand theatre and

drama in an age of transition (pp. 283–292). Brussels, Belgium: P.I.E.Peter Lang.

Mead, H. M. (2003). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia

Publishers.

Meredith, K. (n.d.). Features & reviews: Ava. Retrieved from

http://www.lava.xtra.co.nz/featset.htm

MoMA PS1. (2012). MoMA PS1: Exhibitions: Min Tanaka: Photos by Masato Okada 1975–2005.

Retrieved from http://momaps1.org/exhibitions/view/159

Savigliano, M. E. (2009). Worlding dance and dancing out there in the world. In S. L. Foster

(Ed.), Worlding dance (pp. 163–190). Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Seifert, M. (2011). He rawe tona kakahu/She wore a becoming dress: Performing the

hyphen. (Doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand). Retrieved

from

http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/1786/thesis.pdf?sequence=1

Smith, S. (2012, June). Newsletter. Retrieved from

http://myemail.constantcontact.com/-‐Get-‐to-‐know-‐how-‐you-‐dance-‐-‐with-‐Charles-‐

Koroneho.html?soid=1108931019173&aid=SiJe8kf0HYs

Snow, P. (2002). Imaging the in-between: Training becomes performance in Body Weather

practice in Australia. (Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Sydney, Australia.

Snow, P. (2006). Performing all over the place. In G. McAuley (Ed.), Unstable ground:

Performance and the politics of place (pp. 227–246). Brussels, Belgium: P.I.E. Peter

Lang.

South Island Dance Network. (2012, May 17). News: REMAP forms: Strengthening the

Christchurch Dance Community. Retrieved from http://www.sidn.org.nz/news/239-‐

remap-‐forms-‐strengthening-‐the-‐christchurch-‐dance-‐community

Taylor, G. (2010). Empty? A critique of the notion of 'emptiness' in butoh and Body Weather

training. Theatre, Dance and Performance Training , 1(1), 72–87.

Van de Ven, F., & Snow, P. (2012, February 20-26). From touch and manipulation to

movement and dance. [Workshop]. Auckland, Waitakere, New Zealand: SOUL Centre.

Van Dijk, B. (2011). Towards a new Pacific Theatre. VDM Publishing. Retrieved from

http://www.pacific-‐news.de/pn31/pn31_dijk.pdf

Venu, K. (2006, September). Min Tanaka biography. Retrieved from

http://virali.wordpress.com/2010/01/15/min-‐tanaka-‐biography/

Wood, B. (2010). Making sense of no body. (Unpublished masters thesis, AUT University,

Auckland, New Zealand.

i

http://www.atamiradance.co.nz/about/

ii

Editor’s note, for discussion of Lemi Ponifasio’s approach see:

Ponifasio, L. (2002). Creating cross-cultural dance in New Zealand. In Creative New Zealand (Ed.),

Moving to the future. Nga whakanekeneke atu ki te ao o apopo, (pp.52-56). Wellington, NZ:

Creative New Zealand.

iii These teachers, along with witnessing the work of MAU dance theatre, awoke within me a thirst

for a fresh approach to dance while training and working in the Contemporary Dance scene in

Auckland, New Zealand from 2002-2006.

iv Herron Smith (2010) discusses Lynne Pringle and Kilda Northcott’s dance theatre work Fishnet

(2005), Chris Blake and Stuart Hoar’s opera Bitter Calm (1993), and Gary Henderson’s play Homeland

(2005), as studies for examining Pākehā identity on stage in Aotearoa.

Dance Research Aotearoa, 3, 2015

View publication stats

You might also like

- They're Our Whānau Report - ActionStationDocument33 pagesThey're Our Whānau Report - ActionStationNewshub67% (3)

- The Family History of Louis Hetet - He Korero Whakapapa No Louis HetetDocument16 pagesThe Family History of Louis Hetet - He Korero Whakapapa No Louis HetetLouis Hetet91% (11)

- Reading5-Đã Chuyển ĐổiDocument385 pagesReading5-Đã Chuyển ĐổiThái Văn Tính100% (2)

- ccdn412 Project 1 Decolonisation - Arcadia Branded Tea - Joyce Kim 200494771Document3 pagesccdn412 Project 1 Decolonisation - Arcadia Branded Tea - Joyce Kim 200494771api-269292118Noch keine Bewertungen

- Who Was Louis HetetDocument1 pageWho Was Louis HetetWilliam RogersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology of Dance KaepplerDocument11 pagesAnthropology of Dance KaepplerKaisa KuhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Ethnology and The Antrophology of DanceDocument11 pagesDance Ethnology and The Antrophology of DanceIsrael CamposNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peter Pál Pelbart - Cartography of Exhaustion - Nihilism Inside Out-University of Minnesota Press (2016) PDFDocument101 pagesPeter Pál Pelbart - Cartography of Exhaustion - Nihilism Inside Out-University of Minnesota Press (2016) PDFIan GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Road and The TaniwhaDocument11 pagesThe Road and The TaniwhaShihâb AlenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mbakumba Dance-A Choreomusical Structural AnalysisDocument31 pagesMbakumba Dance-A Choreomusical Structural AnalysisEmmanuel MujuruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Body PercussionDocument7 pagesBody PercussionMarcelo RojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Congress On Research in Dance Dance Research JournalDocument9 pagesCongress On Research in Dance Dance Research JournalLazarovoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gambirasio Semsn 19-1Document6 pagesGambirasio Semsn 19-1lucagambirasio91Noch keine Bewertungen

- 'DQFH (Wkqrorj/Dqgwkh$Qwkursrorj/Ri'Dqfh $Xwkruv$Gulhqqh/.Dhssohu 6rxufh 'Dqfh5Hvhdufk-Rxuqdo9Ro1R6Xpphuss 3xeolvkhge/ Rqehkdoiri 6WDEOH85/ $FFHVVHGDocument11 pages'DQFH (Wkqrorj/Dqgwkh$Qwkursrorj/Ri'Dqfh $Xwkruv$Gulhqqh/.Dhssohu 6rxufh 'Dqfh5Hvhdufk-Rxuqdo9Ro1R6Xpphuss 3xeolvkhge/ Rqehkdoiri 6WDEOH85/ $FFHVVHGGaby López0% (1)

- Perspectives in Motion: Engaging the Visual in Dance and MusicFrom EverandPerspectives in Motion: Engaging the Visual in Dance and MusicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kaeppler - Dance in Anthropological PerspectiveDocument20 pagesKaeppler - Dance in Anthropological PerspectivePatricio FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vertical dance: perceiving and creating space: preface by Margaret WilsonFrom EverandVertical dance: perceiving and creating space: preface by Margaret WilsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Dance Steps in UltaDocument11 pagesTypes of Dance Steps in UltaDIGITAL 143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Ethnology and The Anthropology of Dance Adrienne L. KaepplerDocument11 pagesDance Ethnology and The Anthropology of Dance Adrienne L. KaepplerLiya ShouNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNIT 1 (AutoRecovered)Document3 pagesUNIT 1 (AutoRecovered)Jayra Marie Guiral ChavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro To DanceDocument10 pagesIntro To DanceRon JasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Dance Steps and Positions PDFDocument11 pagesTypes of Dance Steps and Positions PDFRather NotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Going The Distance Locating Journey Liminality and Rites of Passage in Dance Music ExperiencesDocument17 pagesGoing The Distance Locating Journey Liminality and Rites of Passage in Dance Music ExperiencesbenreidoxxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrienne Kaeppler KinemesDocument16 pagesAdrienne Kaeppler KinemesJ100% (1)

- Empty A Critique of The Notion of EmptinDocument17 pagesEmpty A Critique of The Notion of Emptinvladtrueyoungwerther2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- William On 2002Document20 pagesWilliam On 2002celia.jm98Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grau Blacking and Dance AnthropologyDocument12 pagesGrau Blacking and Dance AnthropologyJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peh 11 1 2021 2022Document24 pagesPeh 11 1 2021 2022Nieva Aldiano LaurenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance in The Karo Society: Important To Learning and PracticingDocument14 pagesDance in The Karo Society: Important To Learning and Practicingjhen.efrataNoch keine Bewertungen

- APPLICATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF SPACE, TIME AND ENERGYIN LEARNING DANCE CREATION ‘POSO-POSO NA BISUK’Document8 pagesAPPLICATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF SPACE, TIME AND ENERGYIN LEARNING DANCE CREATION ‘POSO-POSO NA BISUK’AJHSSR JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Politics and Poetics of DanceDocument32 pagesThe Politics and Poetics of Dancefelipekaiserf100% (1)

- To What Extent Should The Body Be Encouraged To Communicate Expression in Music Performance?Document11 pagesTo What Extent Should The Body Be Encouraged To Communicate Expression in Music Performance?Jonathan CornishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Pe3Document36 pagesDance Pe3Genshin ImpactAccNoch keine Bewertungen

- Looking Two Ways by 25thDocument25 pagesLooking Two Ways by 25thsooyeun_youNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geographies For Moving Bodies: Thinking, Dancing, Spaces: Derek P. MccormackDocument15 pagesGeographies For Moving Bodies: Thinking, Dancing, Spaces: Derek P. MccormackDavid ArdiansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cosmic Dance. Correlations Between Dance and Cosmosrelated Ideas Across Ancient CulturesDocument12 pagesCosmic Dance. Correlations Between Dance and Cosmosrelated Ideas Across Ancient Culturesmarcus motaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrienne Kaeppler. Dance and The Concept of StyleDocument16 pagesAdrienne Kaeppler. Dance and The Concept of StylebiarrodNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHS - Grade 12 - Physical Education and Health 3 - Francia, Clarissa E1Document3 pagesSHS - Grade 12 - Physical Education and Health 3 - Francia, Clarissa E1CLARISSA FRANCIANoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance in Contested Land New Intercultural Dramaturgies 1St Edition Rachael Swain Full ChapterDocument67 pagesDance in Contested Land New Intercultural Dramaturgies 1St Edition Rachael Swain Full Chapterterry.mason759100% (8)

- Ethnography As A Tool For Performance.Document23 pagesEthnography As A Tool For Performance.Kirsty Simpson100% (1)

- Kaeppler - ETNOCOREOLOGIADocument5 pagesKaeppler - ETNOCOREOLOGIAMădălina OprescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gerstin 1998 Interaction and ImprovisationDocument46 pagesGerstin 1998 Interaction and Improvisation40004310100% (1)

- La Union Cultural Institute Gov - Lucero Street, San Fernando City, La UnionDocument5 pagesLa Union Cultural Institute Gov - Lucero Street, San Fernando City, La UnionGreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Keevallik - How To Take The Floor As A CouplepdfDocument23 pagesKeevallik - How To Take The Floor As A CouplepdfSer PaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handouts in Path Fit 2Document4 pagesHandouts in Path Fit 2Alvin GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationship Between Music, Culture, and Society: Meaning in MusicDocument22 pagesThe Relationship Between Music, Culture, and Society: Meaning in MusiccedrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kaeppler, A L - American Approaches To The Study of DanceDocument12 pagesKaeppler, A L - American Approaches To The Study of DanceDanielle LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bodily Movement and Facial Actions in ExDocument39 pagesBodily Movement and Facial Actions in ExMarija DinovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond The Silver ScreenDocument22 pagesBeyond The Silver ScreenKawalkhedkar Mohan VinayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music MovementDocument275 pagesMusic MovementIdlgi DiddoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakes Anna Phenomenology DanceDocument18 pagesPakes Anna Phenomenology DanceveronicavronskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Quantitative Research Proposal Presented To The Faculty of The Senior High School Department La Consolacion College BacolodDocument12 pagesA Quantitative Research Proposal Presented To The Faculty of The Senior High School Department La Consolacion College BacolodGlory Neil AñerdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Aesthetics and Cultural Implications: A Case Study of Ekombi Dance and Asian Uboikpa DanceDocument16 pagesDance Aesthetics and Cultural Implications: A Case Study of Ekombi Dance and Asian Uboikpa DanceBounce LightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Ecosystems: Ecological Approaches To Musical InteractionDocument20 pagesPerformance Ecosystems: Ecological Approaches To Musical InteractionFernando KozuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Curriculum and ExperienceDocument22 pagesMusic Curriculum and Experienceapi-146452658Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fernandez+&+Sawney+ +Experimenting+With+Butoh Based+PerformanceDocument17 pagesFernandez+&+Sawney+ +Experimenting+With+Butoh Based+PerformanceisbnvbarcenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cycle of Creativity - A Case Study of The Working Relationship Between A Dance Teacher and A Dance Musician in A Ballet ClassDocument20 pagesThe Cycle of Creativity - A Case Study of The Working Relationship Between A Dance Teacher and A Dance Musician in A Ballet ClassPrdesh NaserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropological Notebooks XVI 3 PusnikDocument4 pagesAnthropological Notebooks XVI 3 PusnikDineshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anderson 2012 Relational Places The Surfed Wave As Assemblage and ConvergenceDocument18 pagesAnderson 2012 Relational Places The Surfed Wave As Assemblage and ConvergenceGareth BreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stanley Umd 0117E 10896.pdf JsessionidDocument212 pagesStanley Umd 0117E 10896.pdf JsessionidAlessandro GuidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Music Therapy GroveDocument12 pages2 Music Therapy GroveIlda PinjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andree Grau Why People Dance - 2016Document22 pagesAndree Grau Why People Dance - 2016Danielle LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MLATISACDC CH 2Document22 pagesMLATISACDC CH 2rolan ambrocioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The International Journal of Screendance Vol 1 PDFDocument144 pagesThe International Journal of Screendance Vol 1 PDFflor.del.cerezoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance As Our Source in Dance/Movement Therapy Education and PracticeDocument15 pagesDance As Our Source in Dance/Movement Therapy Education and PracticeMariano martinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brennan 2017Document23 pagesBrennan 2017Ian GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Drama Review: TDRDocument13 pagesMIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Drama Review: TDRIan GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interface: To Cite This Article: Denis Smalley (1993) Defining Transformations, Interface, 22:4Document23 pagesInterface: To Cite This Article: Denis Smalley (1993) Defining Transformations, Interface, 22:4Ian GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stephen Walker - Gordon Matta-Clark - Art, Architecture and The Attack On Modernism-I. B. Tauris (2009) PDFDocument221 pagesStephen Walker - Gordon Matta-Clark - Art, Architecture and The Attack On Modernism-I. B. Tauris (2009) PDFIan GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theorizing Queer Inhumanisms: DossierDocument40 pagesTheorizing Queer Inhumanisms: DossierIan GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Garner, Aubry Accepted Thesis 5-23-16Document105 pagesGarner, Aubry Accepted Thesis 5-23-16Ian GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feelings and Fractals: Woolly Ecologies of Transgender MatterDocument22 pagesFeelings and Fractals: Woolly Ecologies of Transgender MatterIan GeikeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis FulltextDocument350 pagesThesis Fulltextanon_606305237Noch keine Bewertungen

- Maori History and ProtestDocument18 pagesMaori History and ProtestHelgeSnorriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maori EssayDocument9 pagesMaori EssayPhillip MaddenNoch keine Bewertungen

- NZQA Registration FormDocument2 pagesNZQA Registration FormAleksandarSashaStankovichNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEW ZEALAND - SummaryDocument34 pagesNEW ZEALAND - SummaryMohd FaisalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Framing and Reframing The Agōn: Contesting Narratives and Counternarratives On Māori Property Rights and Political Constitutionalism, 1840-1861Document24 pages7 Framing and Reframing The Agōn: Contesting Narratives and Counternarratives On Māori Property Rights and Political Constitutionalism, 1840-1861Sara CaminoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intelligibility and Meaningfulness in Multicultural Literature in EnglishDocument11 pagesIntelligibility and Meaningfulness in Multicultural Literature in Englishایماندار ٹڈڈاNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purposes For ReadingDocument3 pagesPurposes For ReadingDzul ASamat100% (1)

- Architecture NZ - #5 September-October 2021Document122 pagesArchitecture NZ - #5 September-October 2021林VincentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Culture of New ZealandDocument3 pagesCulture of New ZealandNurul HafizahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Room 11 12 13 Turangawaewae PlanningDocument19 pagesRoom 11 12 13 Turangawaewae Planningapi-541161082Noch keine Bewertungen

- New Zealand CultureDocument1 pageNew Zealand CultureabdulhafizunawalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebook Wars Without End Nga Pakanga Whenua O Mua New Zealand S Land Wars A Maori Perspective Danny Keenan Online PDF All ChapterDocument53 pagesEbook Wars Without End Nga Pakanga Whenua O Mua New Zealand S Land Wars A Maori Perspective Danny Keenan Online PDF All Chapterarethahundarian579100% (10)

- Year 11 Poetry BankDocument4 pagesYear 11 Poetry BankShanshan KongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mate Wareware - Understanding Dementia' From A Maori PerspectiveDocument9 pagesMate Wareware - Understanding Dementia' From A Maori PerspectivedarinkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethnicity, National Identity and New Zealanders':: Considerations For Monitoring Māori Health and Ethnic InequalitiesDocument36 pagesEthnicity, National Identity and New Zealanders':: Considerations For Monitoring Māori Health and Ethnic InequalitiesLucas TobingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terra Australis 35Document212 pagesTerra Australis 35Glenn Denton100% (1)

- Colonisation Hauora and Whenua in Aotearoa-2019Document16 pagesColonisation Hauora and Whenua in Aotearoa-2019Jiayi XueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Māori Teaching and Learning in AustraliaDocument19 pagesMāori Teaching and Learning in AustraliaKiwinKoreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HANSON - The Making of The MaoriDocument14 pagesHANSON - The Making of The MaoriRodrigo AmaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELS Te Whariki Early Childhood Curriculum ENG Web PDFDocument72 pagesELS Te Whariki Early Childhood Curriculum ENG Web PDFSusan Jackman100% (1)

- Rachel Goldstine 734985437Document8 pagesRachel Goldstine 734985437api-468165851Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ielapa 232353170216206Document16 pagesIelapa 232353170216206mahipandya3102Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Day The Raids CameDocument168 pagesThe Day The Raids CameKarolyn MorrisNoch keine Bewertungen