How Should We Teach the Story of Our Country?

Book bans and restrictive laws are threatening to warp the version of American history that kids learn in school: Your weekly guide to the best in books

The past few years have seen an intensifying of the ways politics can intervene in education, including the censorship of books. Lawmakers in Texas have made repeated pushes to restrict the books that kids can access in schools. Leaders in other states across the country have done the same, including in Tennessee, where one local school board infamously banned Maus, a graphic novel that brutally—but honestly—depicts the Holocaust. Under Governor Ron DeSantis, Florida has passed sweeping laws that limit what schools can teach about topics such as gender, sexuality, and race. In January, the state even opposed a whole course, AP African American Studies. (The class’s curriculum has since been revised; Florida has not yet said whether it will actually impose the ban.)

The central issue in many of the recent restrictions is how to teach our country’s history. Although memorizing dates and names can lead students to believe that the subject comprises a series of simple facts about clear-cut events, the truth about the past is much more tangled. Textbooks have long been skewed or have contained errors: In his book Lies My Teacher Told Me, James Loewen analyzes the flaws in a dozen major U.S. history textbooks and provides a sharper retelling of the moments those textbooks distorted. DeSantis also clings to his own version of our past. Take his book, Dreams From Our Founding Fathers, which minimizes the role of slavery in America’s founding and idealizes the men who first governed the country. As David Waldstreicher writes, DeSantis seems to advocate for “never bringing up slavery or race except to praise those who ended it.”

Florida professors are already beginning to worry about how restrictions on what they can teach might threaten their syllabi, whether they cover the Harlem Renaissance or William Faulkner; at least one professor has canceled two of his courses entirely. What students are—and aren’t—taught influences the world in ways that ripple far beyond any one seminar discussion. As the historian Carter G. Woodson put it in his book The Mis-education of the Negro, “There would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.”

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

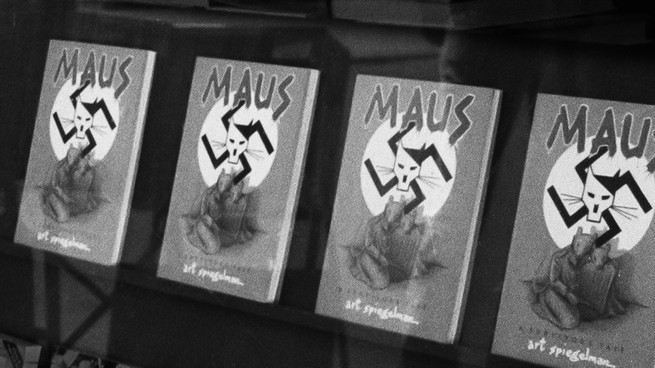

Roger Ressmeyer / Corbis / VCG / Getty

Book bans are targeting the history of oppression

“What these bans are doing is censoring young people’s ability to learn about historical and ongoing injustices.”

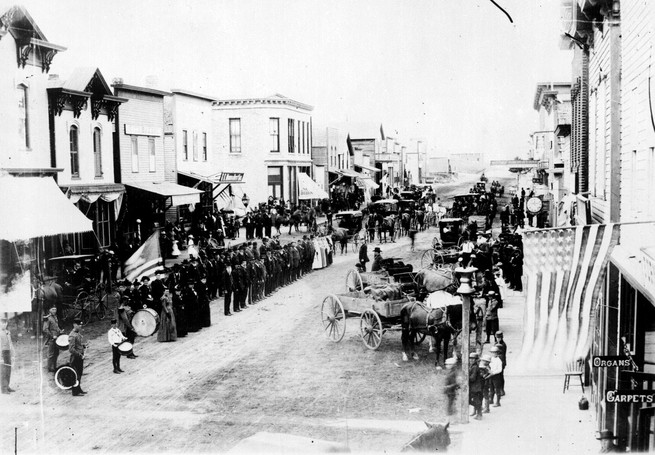

Marion Doss / Flickr

History class and the fictions about race in America

“In history class students typically ‘have to memorize what we might call “twigs.” We’re not teaching the forest—we’re not even teaching the trees,’ said [James] Loewen, best known for his 1995 book Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. ‘We are teaching twig history.’”

Octavio Jones / Getty; The Atlantic

The forgotten Ron DeSantis book

“His entire reading of American history is enveloped in both unquestioning fealty to the Founders and an insistence that the role of slavery, and race more broadly, in that history does not seriously change anything about how we should understand the birth and development of our country.”

Tyler Comrie / The Atlantic

‘Most important, we must not upset DeSantis’

“DeSantis isn’t trying to expunge ideology from education, only ideologies he dislikes, ones that see racism as woven through American institutions or that emphasize diversity, equity, and inclusion instead of merit and color-blindness.”

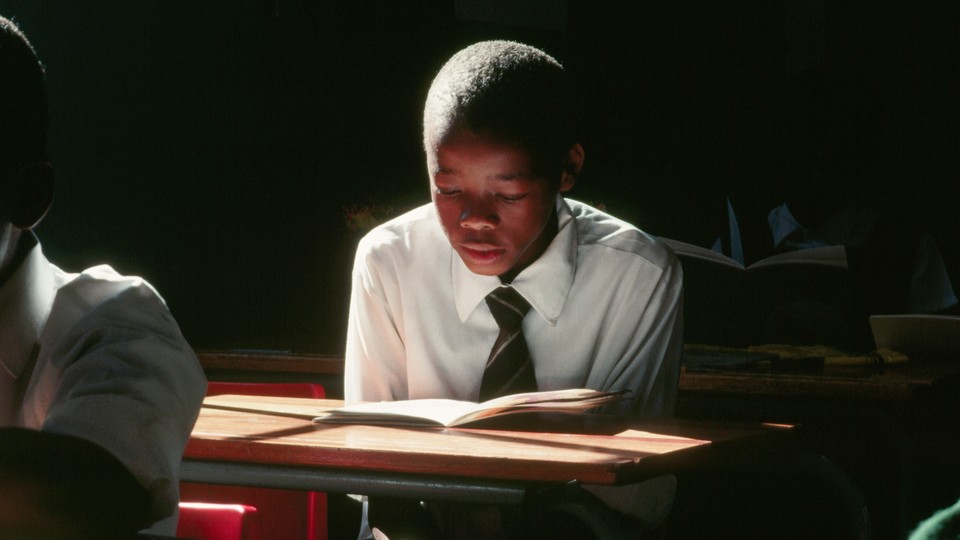

Getty; The Atlantic

The book that exposed anti-Black racism in the classroom

“What does it mean to base the education of Black students on an interpretation of human experience and a set of philosophies and ethics that justified the plunder of Africa and the enslavement of Black people?”

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Kate Cray. The book she’s reading next is The Rabbit Hutch, by Tess Gunty.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.