How FDR Changed Political Communication

The renowned filmmaker Ken Burns has a new project called UNUM, about the sources of connection rather than separation in American life.

His latest segment involves “Communication” in all its aspects, and it combines historical footage with current commentary. Some of the modern commenters are Yamiche Alcindor, Jane Mayer, Megan Twohey, Kara Swisher, and Will Sommer. You can see their clips here.

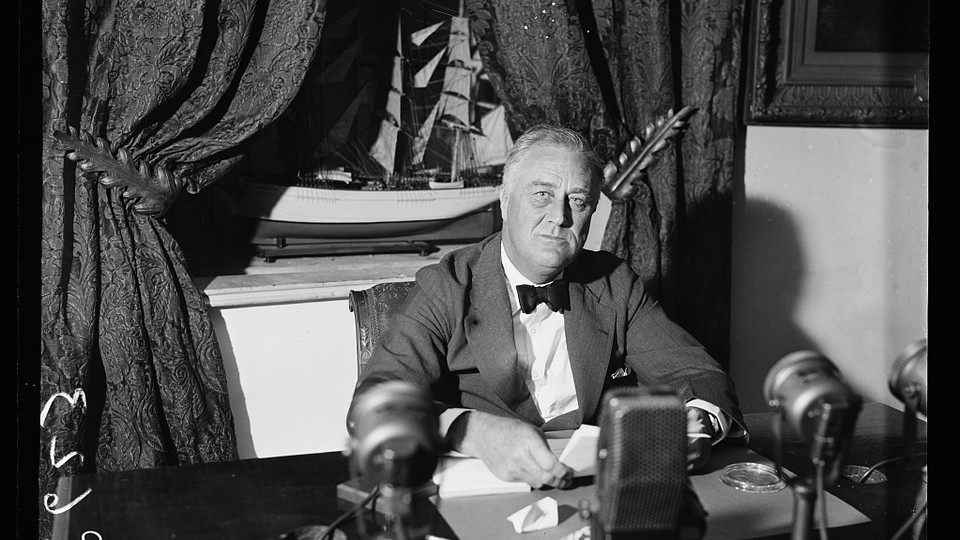

One more of these segments covers the revolution in political communication wrought by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s radio addresses known as “fireside chats.” It was drawn from Burns’s earlier documentary Empire of the Air, which was narrated by Jason Robards. You can see a clip from that documentary here.

As part of the UNUM series of contemporary response to historical footage, Burns’s team asked me to respond to the FDR segment. (Why me? In 1977—which was 44 years after FDR’s first fireside chat, and 44 years ago, as of now—the newly inaugurated President Jimmy Carter gave his first fireside chat, which I helped write. It’s fascinating to watch, as a historical artifact; you can see the C-SPAN footage here.)

This is what I thought about FDR’s language, and how it connects to the spirit of our moment in political time:

For reference, here is the text version of what I said in the Burns video, about those FDR talks, as previously noted here:

The most important words in Franklin Roosevelt’s initial fireside chat, during the depths of Depression and banking crisis in 1933, were the two very first words after he was introduced.

They were: My friends.

Of course political leaders had used those words for centuries. But American presidents had been accustomed to formal rhetoric, from a rostrum, to a crowd, stentorian or shouted in the days before amplification. They were addressing the public as a group—not families, or individuals, in their kitchens or living rooms: My friends. A few previous presidents had dared broadcast over the radio—Harding, Coolidge, Hoover. But none of them had dared imagine the intimacy of this tone—of trying to create a national family or neighborhood gathering, on a Sunday evening, to grapple with a shared problem.

Roosevelt’s next most important words came in the next sentence, when he said “I want to talk for a few minutes” with his friends across the country about the mechanics of modern banking. Discussing, explaining, describing, talking—those were his goals, not blaming or declaiming or pronouncing. What I find most remarkable in the tone that followed was a president talking up to a whole national audience, confident that even obscure details of finance could be grasped if clearly explained, rather than talking down, to polarize and oversimplify.

Consciously or unconsciously, nearly every presidential communication since that time has had FDR’s model in mind. In 1977 the newly inaugurated 39th president Jimmy Carter gave a fireside chat about the nation’s energy crisis, a speech that, as it happens, I helped write. Nearly every president has followed Roosevelt’s example of the basic three part structure of a leader’s speech at time of tragedy or crisis: First, expressing empathy for the pain and fear of the moment; second, expressing confidence about success and recovery in the long run; and third, offering a specific plan, for the necessary next steps.

Some of these presentations have been more effective, some less. But all are operating against the background, and toward the standard of connection, set by the 32nd president, Franklin Roosevelt, starting in 1933. “Confidence and courage are the essentials of success in carrying out our plan,” he said in that first fireside chant. “Let us unite in banishing fear.”

The opening words of that talk had been “My friends.” His closing words were, “Together we cannot fail.”