It’s going to be a hell of a thing to explain to future generations.

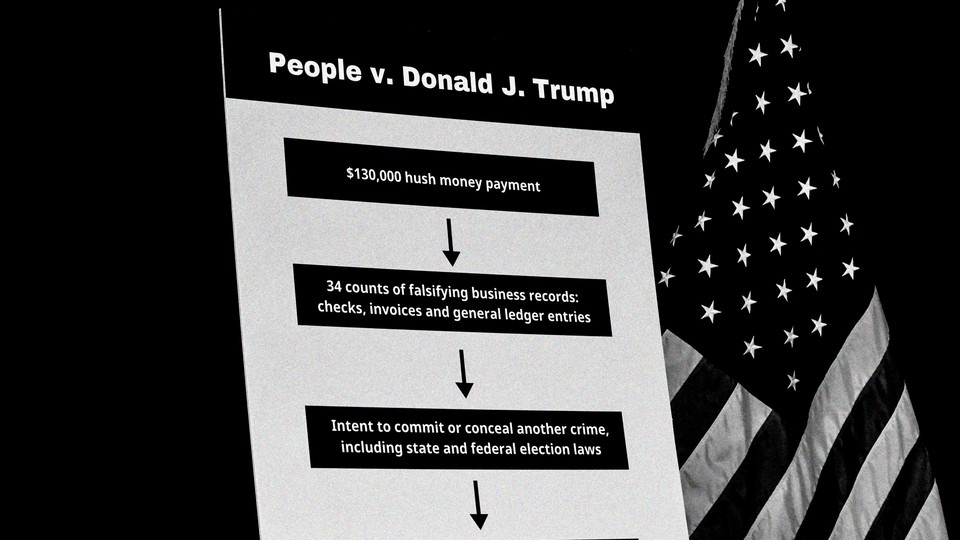

The defeated president of the United States incited an attack on Congress in hopes of preventing a transfer of power. Hundreds of his supporters were prosecuted and sentenced for joining a violent mob. Yet the first indictment in U.S. history of an ex-president arose from his scheme to pay two alleged sexual partners and one witness for their silence about Donald Trump’s sordid personal life.

From the moment rumors swirled that the Manhattan district attorney would move against Trump, many of us felt an inward worry: Did Alvin Bragg have a case that would justify his actions? The early reports were not encouraging. Many Trump-unfriendly commentators published their qualms. Over a week of speculation, though, it seemed wise to withhold judgment until the actual indictment was available to read. Now the document has been published. The worriers were right.

The indictment charges that Trump falsified business records to conceal hush-money payments. There won’t be a lot of skepticism about the charges themselves, not even from most of Trump’s partisans. If any normal business owner were caught tampering with records in this way, he would find himself in serious legal trouble. Yet it’s unlikely that a normal business owner would have been caught, because such behaviors would scarcely have excited enough prosecutorial interest to motivate an investigation. At his press conference on Tuesday, even the DA described these counts of deceptive record-keeping as “bread and butter” charges.

The indictment does not accuse Trump of falsifying records in order to defraud tax authorities, or his lenders, or investors, or even campaign donors. Instead, the indictment accuses Trump of seeking to deceive voters about his dissolute private life. Again, there won’t be a lot of skepticism about that. Trump was trying to preserve an illusion for his supporters, people who had already heard the Access Hollywood audio. As Trump repeated in so many of his speeches: “You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in.” If there was a conspiracy to deceive, Trump’s voters numbered among the co-conspirators.

Which may be why the actual crimes charged in this particular indictment look awfully technical.

Throughout the years of Trump’s presidency, those horrified by his authoritarian impulses have repeatedly bumped up against a quandary: Trump’s most heinous actions are often not illegal; his illegal actions are usually not his most heinous. Precisely because Trump has done so many bad things, those investigating him had both a duty and an opportunity to consider carefully: Is this the particular thing for which they will make history with the first indictment of an ex-president of the United States?

The this in this case seems distinctly underwhelming. We’re about to revert to the turmoil and trauma of the Trump presidency—and for what?

One wonders whether there was not a voice around the prosecutorial conference table who said, “We’ve got him dead to rights. We can indict him; we can probably convict him, probably sentence him. But should we? Or should we let somebody who may be able to prosecute more consequential crimes take the lead?”

The law has many functions in a democratic society. One of them is to educate the public. Since January 6, 2021, a question has hung in the air: Would the mob leader face equal justice as the mob followers? Or would he be protected by some special exemption?

The congressional investigation of the January 6 attack methodically built the case, and compellingly narrated the story, of Trump’s culpability. That account stands as an important achievement and a powerful political fact. But Congress left the legal consequences of its investigation to federal law enforcement. Americans and the world are still waiting to hear whether the Department of Justice will act.

Maybe it will soon. In the meantime, is this the national debate Americans need to guide their understanding of what happened during the Trump presidency, and what might happen again if Trump were returned to office?

As president, Trump demanded and extracted payments from those who sought preferential treatment from the federal government. Favor-seekers got the message that they should stay in Trump’s hotels, book events in Trump’s ballrooms, direct money to Trump’s company. Neither Trump nor his business, the Trump Organization, has been convicted of any offense in those dealings—despite much talk in Washington about the emoluments clause of the Constitution and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. But this past January, the company was found guilty of fraud for falsifying records and cheating on taxes going back years. High crimes indeed.

During the 2008 Democratic presidential-primary campaign, the candidate John Edwards organized payoffs to an ex-lover. He was later charged by federal prosecutors with violating campaign-finance laws. A jury acquitted him on one count and deadlocked on the others. There was no dispute that donor funds had been diverted to Edwards’s mistress (though his lawyers claimed that the money had been a “gift,” not a campaign donation). The jury deadlocked over a balky “This?”

The Trump facts differ from those in the Edwards case in legally significant ways. Trump’s own lawyer in this matter, Michael Cohen, went to prison for his part in the transaction. Yet, with the Edwards example in mind, a prosecutor should consider: Will a Manhattan jury, even if dominated by people who voted against Trump, react to the charge with a similarly disapproving “This?”

Falsifying documents is illegal. Also illegal is committing perjury and inducing others to commit perjury on your behalf. Yet when President Bill Clinton was accused of doing both of those things to cover up an affair with a White House intern, the majority of Americans shrugged off the accusations. Perjury is wrong, they seemed to feel, but the motive for the perjury matters. Perjury to conceal a murder or fraud: very wrong. But perjury to conceal adultery?

Poorly considered prosecutions may offend the public’s sense of fairness, regardless of whether the target is popular. Clinton had won not even 50 percent of the vote in the prior presidential election, in 1996. Two years later, his 73 percent approval rating represented a repudiation of the Ken Starr investigation and the Newt Gingrich–led impeachment. Clinton, too, benefited from a “This?” verdict.

The first criminal indictment of an ex-president is bound to split American society along partisan, ideological, and cultural lines. Trump’s fiercest supporters would defend him against any charge—even, as Trump himself famously said, if he shot someone on Fifth Avenue. But not all Trump supporters are so fierce. A just indictment for a major and consequential crime would pry more of them away than an indictment for a light and technical offense.

Prosecutors would have been wiser to see Trump brought to justice on the most serious legal issues. This Manhattan indictment may, through its sheer pettiness, inadvertently diminish Trump’s misdeeds. It may, even more worryingly, diminish his accusers by casting them—much as Clinton successfully did Starr’s team a generation ago—as prurient snoops.

Prosecutors do not think like politicians, and they should not. Yet they do have leeway to decide which offenses to pursue. As a businessman and as a politician, Trump has broken so many rules that prosecutors in different states and at the federal level can, should, and must reflect on their buffet of options. But if this is indeed all there is, it doesn’t justify inviting the destructive rancor about to explode around us.