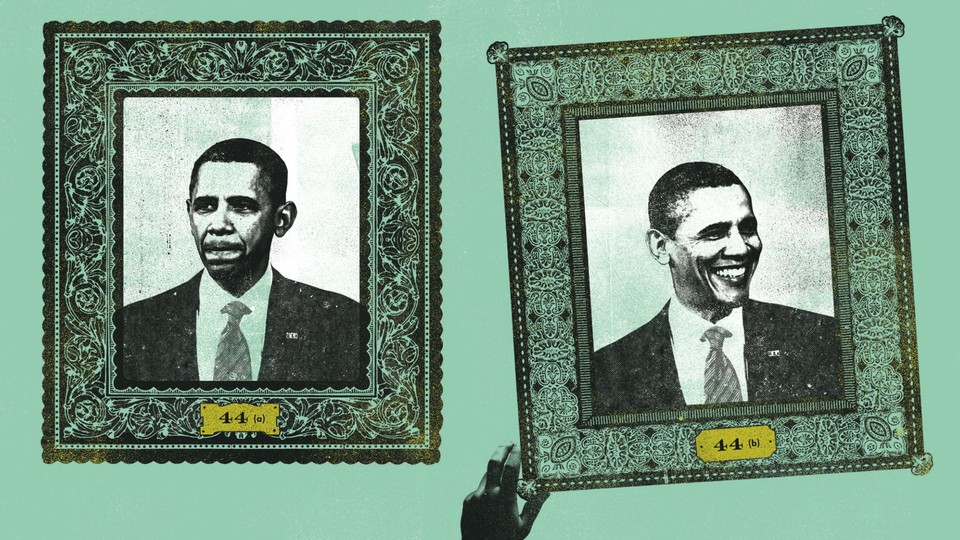

Second Chances

Presidential encores have a reputation for being rocky. But there have been exceptions—and Obama’s new term could be one of them.

Second terms in the White House have, in many cases, ranged from the disappointing to the disastrous. Sick of the political infighting that intensified after his reelection, George Washington could hardly wait to retire to Mount Vernon. Ulysses S. Grant’s second term was plagued by political scandal and economic panic. Woodrow Wilson left office a broken man, having suffered a massive stroke during his failed crusade to persuade America to join the League of Nations. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower was routed in his last political battle, leaving Democrats in control of the presidency, the House, the Senate, and the Supreme Court for nearly the rest of his life. More recently, Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace; Ronald Reagan was tarred by the Iran-Contra scandal; Bill Clinton was impeached; and George W. Bush watched helplessly as his opponents surged into both houses of Congress and then the White House.

Hence the legendary “second-term curse.” In the early days of the republic, second-termers were by tradition discouraged from seeking another term, and nowadays, presidents are legally barred from a third term, thanks to the Twenty-Second Amendment. Popular wisdom has it that second-termers are therefore lame ducks. Unable to run again, how can a term-limited president reward his allies or restrain his adversaries? If he is seen as a fading force, won’t his allies hitch themselves to the next rising star? Won’t his adversaries attack relentlessly?

Fortunately for Barack Obama, the situation is not that bleak. For one thing, the idea of a second-term curse fails to account for basic probability. Most presidents fail in one way or another, and many nose-dive so fast that they never get a second term. Perhaps the “curse” is actually an example of what statisticians call “regression to the mean”: those presidents who beat the political odds in term one usually cannot maintain their lucky streak in term two. Nor does the curse account for several exceptional presidents whose authority increased following reelection. By looking at these two-term stars more closely, we can see how and why Obama might be more blessed than cursed.

From our nation’s founding to the present, politics has followed a tidal pattern. Once a party devises a new and successful electoral formula—a workable coalition that can consistently outnumber the opposition—that party tends to win, and keep winning, until eventually, the tide changes and the other party takes the lead. So far, U.S. history has seen four such reversals, each of which coincided with the election, and reelection, of an exceptional president. Yes, each of the four figures who presided over these great shifts—Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, and Ronald Reagan—had his share of second-term tribulations and catastrophes. (Lincoln, of course, died weeks after delivering his epic second inaugural address, and only days after Lee’s surrender.) But thanks to his own exceptional skills, as well as the fragility of the opposition party, each man forged a new electoral coalition that kept winning long after he left office.

The first turning of the political tide occurred shortly after George Washington’s death. In 1800, Jefferson’s triumph over John Adams marked the beginning of the end of the Federalist era. In 1804, Jefferson won a second term, and in 1808 he transferred power to his political lieutenant, James Madison. Jefferson and Madison’s Democratic-Republican Party (later renamed the Democratic Party) remained America’s dominant presidential party until the Civil War era, when the tide turned a second time. Lincoln, a Republican, won, won again, and (in the election following his assassination) was succeeded by a political heir, Ulysses Grant. Republicans dominated the presidency until the Great Depression—and FDR’s election and reelections—marked a third tidal shift. The Democrats’ resulting New Deal/Great Society coalition generally held until it was ripped apart by the Vietnam War and the migration of white southern Democrats to the GOP. Enter Ronald Reagan, whose two terms marked a fourth turning of the electoral tide.

We have been living in the Reagan era ever since. But now, inexorable forces—the changing voting habits of women and young adults, the rising political power of nonwhites and immigrants—mean that the Reagan electoral formula, with its reliance on southern whites, tax-averse businessmen, evangelicals, and Catholics, no longer yields a working majority. The tide may be turning back to the Democrats. Obama’s reelection is particularly historic given modern Democratic presidents’ track record of failing to win the popular vote. He is only the second Democratic president since the Civil War to win two popular majorities—the other was FDR (who, of course, won four). Since Lincoln, in fact, only four Democrats have won even one popular-vote majority—and that tally includes Jimmy Carter, with 50.1 percent of the vote. Bill Clinton never had a popular majority.

So what lessons might Obama borrow from his successful two-term predecessors to avoid being perceived as a lame duck? First, though he cannot succeed himself in 2016, he can designate a proxy to replace him—a loyal lieutenant willing to help his friends, smite his foes, and keep his secrets long after he leaves office. Reagan fared as well as he did in part because he had designated George H. W. Bush as his wingman, and in effect won a third term when Bush became “Bush 41.” By contrast, Eisenhower kept his vice president, Richard Nixon, at a distance. (When asked during the 1960 general election whether his administration had adopted any major ideas of Nixon’s, Ike replied, “If you give me a week, I might think of one.”) The Lewinsky scandal drove a wedge between Clinton and his wingman, Al Gore. A successor—or the lack of one—can shape not just a president’s performance, but also his legacy. When George W. Bush’s time was up, his party tapped John McCain, a White House outsider whose relationship with the president was feisty and rivalrous.

Second, Obama should take advantage of his relative youth, which gives him a distinct edge over most of his predecessors: Until recently, most second-term presidents were well past their prime, both physically and mentally. At age 51, Obama can remain a potent political force even in retirement; he should exploit this fact to enhance his current clout. (Only Grant and Clinton were younger than Obama at the start of their second terms—and think of how Clinton has remained relevant in recent years.)

If he’s to beat the second-term curse, Obama will also need to go bold and big. Just as FDR’s New Deal programs and Reagan’s tax cuts won over whole generations of voters, Obama must find ways to entrench his own legacy—and in the process, his new base. Immigration reform, for example, could draw the kind of young, highly skilled workers who might be able to pay for Social Security benefits for retiring Baby Boomers. Election reform might restore the luster of American democracy—while making it easier for Democratic voters to cast ballots.

One caveat: big changes like these can’t succeed unless another big change comes early in term two—Senate filibuster reform. The signature accomplishment of Obama’s first term, Obamacare, crowded out other reforms because Senate Democrats had to scrape together 60 votes to avoid a filibuster, rather than the simple majority the Constitution requires for passage of a law. If Senate reformers can tame the filibuster early in Obama’s second term—and it appears that Democratic leaders are indeed serious about changing the Senate’s rules this January, using a party-line vote to limit the minority party’s power to slow or stop legislation—then the political picture will change dramatically.

Without filibuster reform, the 45 Republicans in the Senate can quietly block up-or-down votes, with the result being that individual senators from moderate states don’t have to visibly go on record voting against popular Obama agenda items. But if the filibuster were blunted, and only 51 senators’ votes were needed, many key bills would pass with or without the GOP, and some savvy Republicans would choose to swim with the larger electoral tide. Americans would begin to see Republicans and Democrats working together again in the Senate—and this could change dynamics in the House.

And if not, there’s always 2014. When it comes to midterm elections, lameness, handled deftly, can be a source of strength. In 2008, Obama ran as a uniter; had he campaigned aggressively against House Republicans in either 2010 or 2012, he might have tarnished his image, and imperiled his own reelection prospects. But this time around, there’s nothing to stop him from going after those who obstruct his agenda. Beware the lame duck: he can bite hard.

By then, in any case, most eyes will be turning to the 2016 campaign trail. Which brings us back to our first lesson—possibly the most important one: each previous tide-turning president was succeeded in the next presidential election by a handpicked ally. Like Reagan, Obama has a possible wingman in his vice president. Joe Biden could dutifully offer to replace him, thus safeguarding Obama’s power throughout his second term and beyond. But Obama has at least one other outstanding option: just as Jefferson handed presidential power to his talented secretary of state, James Madison, Obama could do the same with Hillary Clinton.

Ultimately, nothing succeeds like succession.