I Tried to Pick America’s Future Political Stars and Didn’t Come Close

The exercise, conducted for The Wall Street Journal 31 years ago, now shows that early success doesn’t portend lasting impact.

One went to Congress, served on the House Rules and the Ways and Means Committees—and now toils as a county commissioner. Another was a scion of a powerful business and political family, became lieutenant governor, narrowly missed being elected to Congress—and now gives speeches about depression and is working on a novel. A third hoped to be on the Federal Reserve board—and is now pursuing Japanese flower arranging. Two went to jail, one of them twice. One has been chair of the Democratic National Committee twice.

These are some of the political stars of the future I profiled in the pages of The Wall Street Journal 31 years ago—a long-ago time when Michael Douglas declared greed to be good, when Ronald Reagan urged Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall, when Jim Bakker resigned from his PTL Club pulpit, and when I was a young political writer given a prized assignment: Look across the country—dig into state legislatures, examine grassroots political organizations, roam the halls of Congress—and identify the 10 people who would dominate American politics in the 21st century.

Sadly, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump did not make the Journal Ten. No one on Earth envisioned any of them living in the White House. Nor did Paul Ryan, Elizabeth Warren, or Kamala Harris make the cut. They were living in true obscurity. Mike Pence was about to lose a House race. Hardly anyone even in his Indiana district paid him any mind. Sonia Sotomayor was on the State of New York Mortgage Agency board. No one thought that was a launching pad to the Supreme Court.

But as I reconnected in recent months with all 10 of those who were on the list—the two who hoped they might be chosen vice president but weren’t, the one who thought she would help elect her presidential candidate but didn’t, and the one who, after getting in a bad bicycle accident, abandoned thoughts of running for office and is now running to stay healthy—it became clear that, in the lives of the politically gifted as in the lives of the rest of us, the state of the family is more important than the state of the nation. And as I evaluated what happened to these men and women of great potential, it was evident that nearly all of them regarded their political lives as peripheral to their personal lives.

“I had great success early,” said John Rowland, who served in Congress and won three terms in the governor’s chair in Connecticut before serving two terms in prison. “Sometimes success in the early years makes it hard to get wisdom. But there’s a lesson: Hold on to what is important in life—faith, family, and friends.”

Indeed, reuniting with these men and women who had great futures in their past provides a fascinating testimony to what matters in their lives and in life itself, which in many of these cases was good works far outside politics. And the astonishing ties among the members of the Journal Ten—none of whom knew one another when the original piece was published in 1987—provide evidence that partisanship and ambition are not necessarily barriers to human impulses. Mari Maseng Will, who prepares Republican candidates for televised debates, and Donna Brazile, the two-time Democratic chair, have become close friends. Pat Nolan, a former Republican leader of the California State Assembly, counseled Rowland on what to expect in prison.

For some of the Journal Ten, the national exposure that the piece provided was but a preface to greater attention in ever greater roles. For others, it was their single heady moment in the spotlight. Scott McInnis, a Republican state representative in Colorado at the time of his selection, framed the piece, the only newspaper clipping he ever placed behind glass. “It was,” he said, “a big, big deal to me.”

Here are the 10 people the Journal identified three decades ago as the great stars of our time, and what happened to them in the period between the Ronald Reagan presidency and the Donald Trump administration:

CHET EDWARDS (1987: Democratic state senator from Texas)

The onetime youngest member of the Texas Senate and the protégé of longtime Representative Olin Teague of College Station, Texas, Edwards emerged as one of the most innovative lawmakers in Austin, co-authoring a state deregulation statute, writing a plan to encourage agricultural diversification in the state, and sculpting a legislative package that restructured universities’ research programs, encouraged women and minorities to enter engineering fields, and clarified university intellectual-property policies.

Edwards served in the Texas Senate for eight years and then moved to Congress, where his district included George W. Bush’s Crawford presidential retreat and where he eventually became chair of the Appropriations subcommittee on military construction and veterans’ affairs—and was one of the figures Senator Barack Obama vetted to be his running mate. He was swept out of office in the anti-Democratic wave of 2010 and now holds the W. R. Poage Distinguished Chair of Public Service at Baylor University, is a partner in a Dallas accounting firm, and is co-chair of the Arlington National Cemetery advisory committee.

“Life turned out far better for me than I expected in 1987,” he said. “I went from being a 35-year-old bachelor to a very happy husband and father of two sons. The biggest change in my life in these 31 years is that new dimension of family that made life more meaningful.”

PATRICK J. NOLAN (1987: Republican state-assembly leader in California)

He volunteered for Ronald Reagan’s 1966 gubernatorial campaign, was a leader of the Young Americans for Freedom, created one of the most effective political operations in California history, and had his eye on the speakership of the state assembly, then perhaps on becoming attorney general and eventually governor.

“Life didn’t turn out for me the way I expected,” he said. “I seemed on the fast track. From the beginning, I felt God’s hand on me and an assurance he was with me and would guide me.” There was a pause, and Nolan teared up and apologized, explaining that he eventually served 29 months in prison for racketeering. “It wasn’t a path I would have chosen, but God used that experience,” he said.

Nolan eventually worked for 18 years with Charles Colson, who went to prison on obstruction-of-justice charges in the Watergate scandal and founded the Prison Fellowship. Like Colson, Nolan—once at the forefront of the drive to retain capital punishment in California—grew committed to prison reform. He and fellow WSJ future star Brazile, among others, sponsored a Washington conference on criminal-justice reform, and he has emerged as one of the most prominent conservatives rallying to the cry of overhauling the prison system.

“When Pat was in the legislature, he was a standard law-and-order conservative without any understanding of the consequences of our prison system,” said David Keene, former chairman of the American Conservative Union. “He came out with a far different perspective, and he understood that it didn’t work at all.”

Today, Nolan, who recalls the television cameras that were at the prison gates “to record my debasement,” argues that the sense of redemption at the heart of the American character is absent in U.S. prisons. “Prisons are for people we are afraid of,” he said. “What we do is stupid—but also wrong morally. No sentence for a crime should do more damage than the underlying crime itself.”

ROBERT KERR III (1987: Democratic lieutenant governor of Oklahoma)

The grandson of the late Senator Robert Kerr—who in his trademark hopsack blue shirt and red suspenders was a fabled orator, the Capitol Hill spokesman for Big Oil, and the architect of massive water projects that brought life to much of dry Oklahoma—Kerr was marked early for success. He served a single term in the state House before becoming lieutenant governor, and his emphasis was on economic development at a time when the collapse of agriculture and oil transformed the state from prosperity to distress.

His route to bigger things ended when he lost a Democratic primary to Bill Brewster, whose two children were killed in an airplane crash the day he announced his candidacy to succeed longtime Representative Wes Watkins in 1990. That made it impossible for Kerr to prevail over a rival draped in tragedy. “He would have been elected to Congress,” said Robert Henry, a former state attorney general, “and who knows how high he could have gone.”

Instead, he was laid low by repeated bouts of depression, was divorced, sought treatment, went into public finance and investment banking, and now is a petroleum landman, identifying real-estate ownership and operating as a lease agent for drilling. But his greatest impact may be in speeches in which he seeks to explain the effects of depression.

“That old public-service inclination has kicked in, so I can be a voice in fighting the stigma of depression and advocating for better mental health in our state,” he said. “So many people don’t have to be handicapped by this if we would just take care of people.”

MARI MASENG WILL (1987: press secretary for Robert Dole’s presidential campaign)

She once covered the crime beat for the Charleston, South Carolina, Evening Post; was an aide to Nancy Reagan; was a speechwriter for President Reagan; worked for both Robert and Elizabeth Dole; was director of the White House Office of Public Liaison; served as a vice president of Beatrice Companies; helped Cindy McCain with her 2008 Republican National Convention speech; and, four years after the original Journal piece was published, married the columnist George F. Will.

Today, Mari Maseng Will specializes in debate prep for Republican candidates, working on the campaigns of such figures as Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin, Governor Rick Perry of Texas, Senator Mike Lee of Utah, and Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska.

“I help people get their message out, and I love it because it requires me to be constantly up for all the issues and working for people who believe in what I believe in,” she said. “Every candidate is different; all have different gifts. There’s no template, but there is a method: You understand the strategy of their race, and you get them to refine what they want to say through discipline.”

TERESA VILMAIN (1987: chief Iowa organizer for Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign)

As one of eight children, Vilmain realized early the importance of organization, a lesson she took from her family and applied to politics. She worked for Gary Hart’s 1988 presidential campaign and then moved to Dukakis’s, providing the Massachusetts governor with a statewide organization and an army of volunteers. In doing so, she was described by former Representative Bob Edgar of Pennsylvania as “visionary in terms of organization.” Phil Roeder, then an Iowa Democratic Party official, credited her with “infectious energy and commitment.”

Vilmain, who now lives outside Madison, Wisconsin, was for a time the most sought-after Democratic political organizer in the country. “I didn’t have a cult following,” she said. “I just worked for people who did.”

Today, Vilmain is undertaking projects to register people to vote—especially the young, the unmarried, and people of color—and to encourage women to be more engaged in ballot measures, candidates, and issues. She is also involved in the Rockefeller Family Fund, specializing in economic justice for women.

After a bike accident, she decided to train for triathlons. “I’m just trying to stay healthy,” she told me. “I never did that back when you first interviewed me. I’m living more healthily than I did back then.”

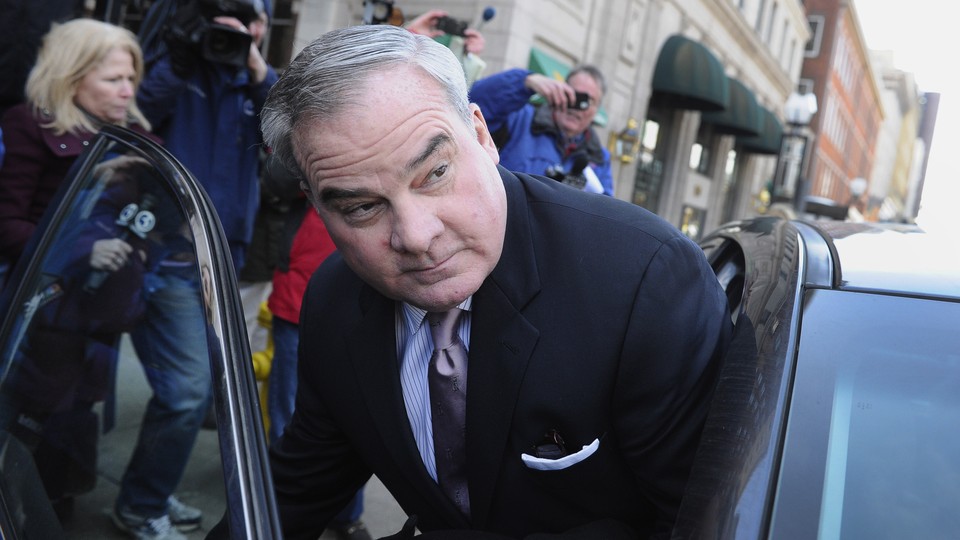

JOHN ROWLAND (1987: Republican congressman from Connecticut)

The first Republican state representative from Waterbury in a century, Rowland moved fast, becoming minority whip in the House chamber in Hartford after only two terms, defeating three-term Representative William Ratchford to become the youngest member of the U.S. House, then becoming governor, the first in two centuries to win three terms. Among other things, he implemented a plan to provide health insurance to children and fostered economic development in the state’s cities.

Then things fell apart. He resigned the governorship and went to jail for mail and tax fraud in 2005, was released, and rebuffed an invitation from Colson to join the Prison Fellowship. “I said, ‘No, I had bigger fish to fry,’” he recalled. But Rowland returned to jail a decade later, this time for election fraud. He was released in May, worked for a time booking weddings at the Chippanee Country Club in Bristol, Connecticut—and finally joined the Prison Fellowship, where today he handles the Northeast as development director.

“I learned the wrong lessons in politics,” he said. “Politics is not the real world. Everyone in Washington is so self-important, thinking they are changing the world when they are really running in place.”

He said he would dissuade any young person from running for Congress. “If you want to be in politics,” he said, “be a selectman in your town.”

DONNA BRAZILE (1987: national field director, Richard A. Gephardt’s presidential campaign)

The daughter of a janitor and a maid, a Louisiana State University activist, and a Carter-Mondale organizer at age 16, a young Brazile wrote in her diary that she wanted to manage a presidential campaign someday. In 2000, she became the first black woman to reach that position, directing the Al Gore campaign.

In the years since that diary entry, she has become one of the most prominent Democrats of her era. She emerged on the national scene in Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign, was a prominent figure in the effort to win a Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, and was a center of controversy for sharing debate questions with the Hillary Clinton campaign. Along the way, she has taught college and lectured at 215 universities.

She also served on the board of directors at the Louisiana Recovery Authority after Hurricane Katrina wreaked its devastation. “I’ve had several stumbling blocks in my career,” she said, “but I never anticipated that a major hurricane would destroy my hometown of New Orleans and set my family back a decade.”

Brazile has often said she wants to be a university president by age 60. She turned 59 this month.

SCOTT McINNIS (1987: Republican state representative in Colorado)

McInnis’s star shone bright from the start. A former police officer and fourth-generation Coloradan who won his state House seat by 13 votes, the closest legislative race in Colorado history, he became chair of the state House Agriculture, Livestock, Natural Resources and Wildlife Committee and—in large measure because of his skill in appealing to environmentalists, hunters, and energy interests—was being groomed for a seat in Congress when the original Journal story appeared.

He won that seat, kept it for six terms, served on both the Rules and the Ways and Means Committees, and returned to Colorado, in part to care for his aging parents. He fought off a messy claim of plagiarism and narrowly lost a gubernatorial race. Then he went into business but had what he described as “heavy withdrawal pains of missing politics.” So he ran for, and won, a seat as a Mesa County commissioner.

“I’m thoroughly enjoying it,” he said. “I don’t have to travel. I think I bring some value to this job. I had a great run in Congress, but I got what I wanted. I spent some time with my folks, and they’re gone now. And I am really enjoying this. Here, we’re not only the legislative branch—we are the executive, too.”

ALAN WHEAT (1987: Democratic congressman from Missouri)

A black man who won his congressional seat in a white district, Wheat became the youngest person ever to be appointed to the powerful House Rules Committee, and emerged as one of the brightest stars in the Democratic firmament—a potential speaker of the House, perhaps more. He was, according to the late Representative Richard Bolling, a onetime legendary Rules Committee chairman and the man Wheat replaced in Congress, “above all things, a learner.”

After six terms in the House, he sought to fill the vacancy left by the retirement of the iconic Republican Senator John Danforth in 1994. “You’ve heard of John Ashcroft?” Wheat asked in a reference to the former senator whom George W. Bush selected to be attorney general. “I’m the reason why.” Ashcroft, at the time a former governor of Missouri, defeated Wheat by 24 percentage points to go to the Senate.

Wheat went to work for CARE, the hunger-relief organization, and then served as a top executive in Bill Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign. Clinton offered him several positions in his second administration, but Wheat was content to remain a Washington government-relations specialist. Today he says he is proud of his time on Capitol Hill but is prouder still of his children.

“I grew up in a cause-oriented family, and the years in public office honed my skills and whetted my appetite for service,” he said. “I wouldn’t trade this life for anything. I’ve had a very happy and rewarding time.”

ELISE PAYLAN SCHOUX (1987: executive assistant to a member of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board)

Schoux was at the center of an angry confrontation that at age 26 she helped stage between Dole, then the powerful chair of the Senate Finance Committee, and Senator Robert Kasten of Wisconsin; for weeks it paralyzed the Senate in an arcane dispute over whether taxes should be withheld from personal savings accounts. She later was the staff director for economics for the 1984 Republican platform, helped shape the tax-overhaul plan that led to the landmark 1986 tax bill, and harbored dreams of being appointed to the Federal Reserve, perhaps as chair.

She left Washington two years after appearing on the Journal Ten list, moving to New York to pursue what she now regards as “the fantasy of working on Wall Street.” She hated every minute there. Eventually she married a man who was a retired USAID official, and started a mom-and-pop consulting operation, working in Bosnia, Kosovo, and East Timor, among other places. She cared for her husband during his seven-year Alzheimer’s-disease ordeal, got her master’s degree in accounting, and is now pursuing Japanese flower arranging.

“I never did become chair of the Fed,” she said, “but I had a better life than I thought I would have, even with the ups and downs.”

And now one more: DAVID SHRIBMAN (1987: political reporter in the Washington bureau of The Wall Street Journal)

I’m now the executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, having left the capital 16 years ago. I learned much in this reporting exercise—about values and what is valued, about life and how it should be lived. I learned that early achievement does not necessarily portend lasting impact, and—this from those many who did not make the Journal Ten and who occupy important posts in the White House and across the capital and the country—that the race sometimes is to the runner who starts late, or who has great imagination, or great determination, or great courage and perseverance.

I learned, too, the truth in what Rowland said in one of our interviews about life after two trips to prison: that each person’s passage is a plan, “and you have to figure it out and jump on the bandwagon.”