What Might Animals Look Like Thousands of Years From Now?

A new pop-up book imagines how Chicago’s ecosystem might evolve in a world with fewer humans.

It’s early May of the year 4847, and Willek Muriday, a chief scientist and regional director of a far-reaching biological survey, has just submitted a report on the Cagoan District, the ruins of an ancient urban center. These ruins, southwest of Lake Mishkin, were long thought to be lifeless, but year-round tropical temperatures and high levels of background radiation have led to the rapid evolution of a number of new species. “The district of Cago is alive and thriving!” Muriday writes.

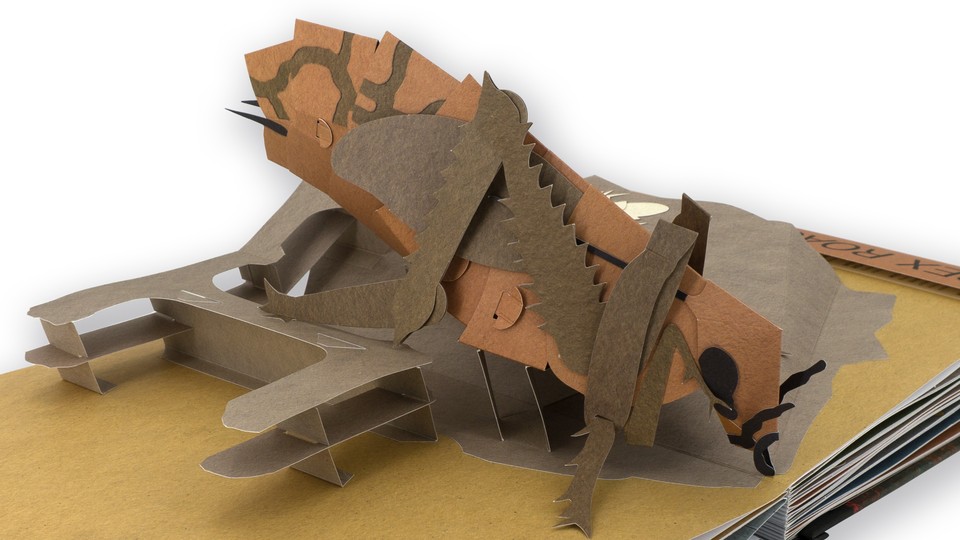

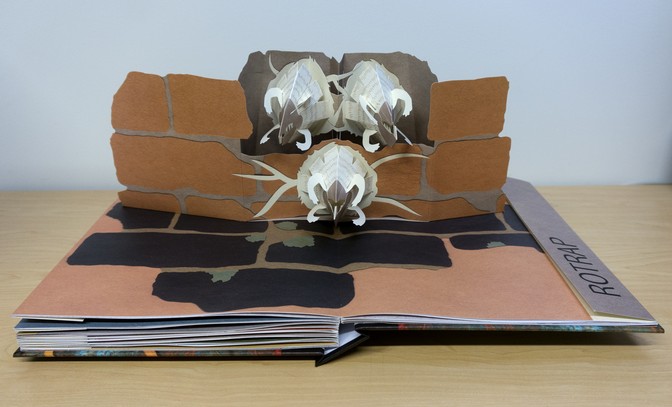

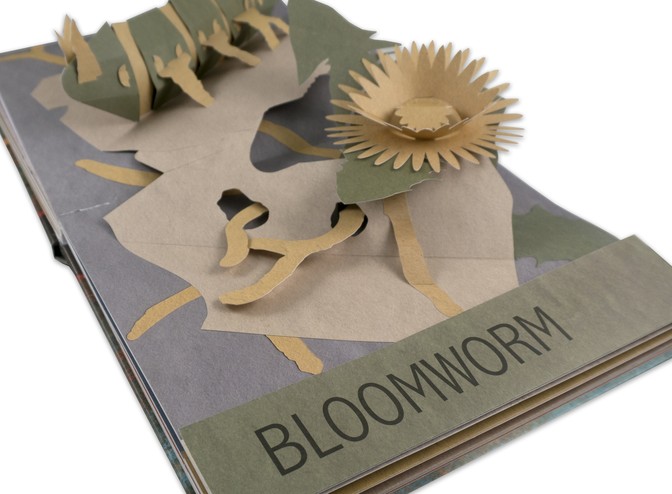

This is the premise of Beyond the Sixth Extinction, a creepily beautiful new pop-up book by Chicago paper artist Shawn Sheehy. The large-format book is ostensibly for older tweens and younger teenagers, and lavish bogeymen literally leap from its pages: Its bestiary includes a mobile, nearly life-size representation of the rex roach, a species evolved from the common cockroach; a massive snapping turtle called the Cagoan dragon; and a flightless pigeon large and fierce enough to eat small mammals. Then there’s the mudmop, a descendant of the catfish. Inconsistencies in counts of the mudmop’s mouth tentacles, Muriday soberly reports, were not clarified “until biologists realized that some of the ‘tentacles’ were not what they appeared to be.” The extra tentacles turned out to be parasitic leeches. Gross!

Though Beyond the Sixth Extinction can be enjoyed solely for its dystopian yuks, its elegant paper sculptures tell a deeper story. The book doesn’t spend much time blaming humans for the world it imagines, or spell out exactly what has befallen Homo sapiens during the nearly three millennia between 2019 and 4847. But it does hint at a world in which the human footprint has been radically reduced. Chicago transformed into the diminished district of Cago, and life to some extent has moved on without us.

All the creatures in Muriday’s imaginary field guide have evolved to take advantage of—and to some extent compensate for—human misrule. Rex roach, which like its smaller forerunners has a high tolerance for radioactivity, can neutralize the radioactive particles it digests. The clam fungus, whose ancestors lived on trees, now clusters on the surfaces of ancient landfills, where it gleans from methane gas the same elements its bracket fungus ancestors mined from wood. (The clam fungus prudently closes its brackets at sunrise, partly to protect its tender inner flesh from those hungry giant pigeons.) The mudmop sequesters heavy metals, as does the Cagoan dragon. The Peteybug’s name derives “from PT bug, for polymertrophic”—a synthetics feeder, it eats compact discs. The bloomworm, the naturalized descendant of a “genetically engineered chimera” that 21st-century researchers hoped would fight cancer, takes root in the cracks in buildings and sidewalks, absorbing calcium and aluminum from the cement and causing “concrete-based structures to deteriorate at an accelerated rate.”

Sheehy’s project was initially inspired by paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey’s 1995 book The Sixth Extinction (not to be confused with Elizabeth Kolbert’s 2014 book of the same name). “That was the first time I’d ever thought about the Earth’s five big extinction events, and that the sixth one, which might have the same sort of drama, is our fault,” Sheehy says. “That had a profound impact on me.”

Sheehy, a former elementary-school teacher, is careful not to burden his young readers with real horrors. As in his previous pop-up book Welcome to the Neighborwood, a much cuddlier tale about real-life animal builders, his primary goal is to provoke curiosity about “what else is out there that we don’t know about yet”—whether “out there” is the backyard or the distant future. The creatures of Beyond the Sixth Extinction, like the scientifically informed inventions of novelists Paolo Bacigalupi and Jeff VanderMeer, are just familiar enough, and plausible enough, to root in the imagination, and its passing place references—the “Cagoan District” includes the “Ohare Site,” infamous among 21st-century travelers—add to its eerie believability. As a contemplation of adaptability, resilience, and the many possible consequences of the present for the future, Beyond the Sixth Extinction can be an adventure for former teenagers, too.