Tweeting the Talmud

The ancient text was never intended for Twitter. Then again, it was never intended for women either.

“The words of the Torah should be burned rather than entrusted to women.” This is the stinging opinion of Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus, a second-century Jewish scholar, as expressed in the Talmud, a 63-volume work of intricate Jewish legal debates, composed from the second to sixth centuries and redacted in Babylonia. Only a few women are mentioned in its 2,711 pages.

The very same sage elsewhere stated that a man who taught his daughter the Torah was teaching her frivolity, wasting his precious time. I take comfort in Ben Azzai, the sage who rejected Hyrcanus’s opinion and obligated fathers to teach their daughters. I think of my two very intelligent aunts, 18 centuries later, who were not allowed to go to college, because they were just going to get married anyway. Rabbi Hyrcanus wasn’t wasting his time. My grandfather wasn’t wasting his money. Neither aunt is married.

I wanted to study the Talmud because it is foundational to literate Jewish life. Knowledge is spiritual power. As a teenager, Ben Azzai’s encouragement mattered; I began parsing the Talmud’s difficult Aramaic passages—passages made even harder by their lack of punctuation and paragraph breaks. I studied it slowly, line by line, in high school, during a gap year in Jerusalem, and in university. I had trouble mastering a page, let alone a chapter, but I was in it for the depth.

By the age of 46, however, I wanted to see the Talmud’s breadth. I began Daf Yomi (literally “a page a day”), a cycle of learning one folio page (two sides, a and b) of the Talmud a day. It’s a seven-and-a-half-year project, undertaken simultaneously across the globe: the same page each day, no matter where you are. (One afternoon, on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, a stranger walked by me in the café car, saw my open Talmud, said “32b,” and kept walking). The pace of the project is staggering. A friend described Daf Yomi as forgetting one page of the Talmud a day.

Every once in a while, I’d encounter a text that had a jarring run-in with modernity. When I encountered, for example, a quip about what women should study—“Women’s wisdom is solely in the spindle”—I laughed. I can barely sew a button on a shirt.

But my 21st-century spindle is Twitter. It can spin anything. And it has.

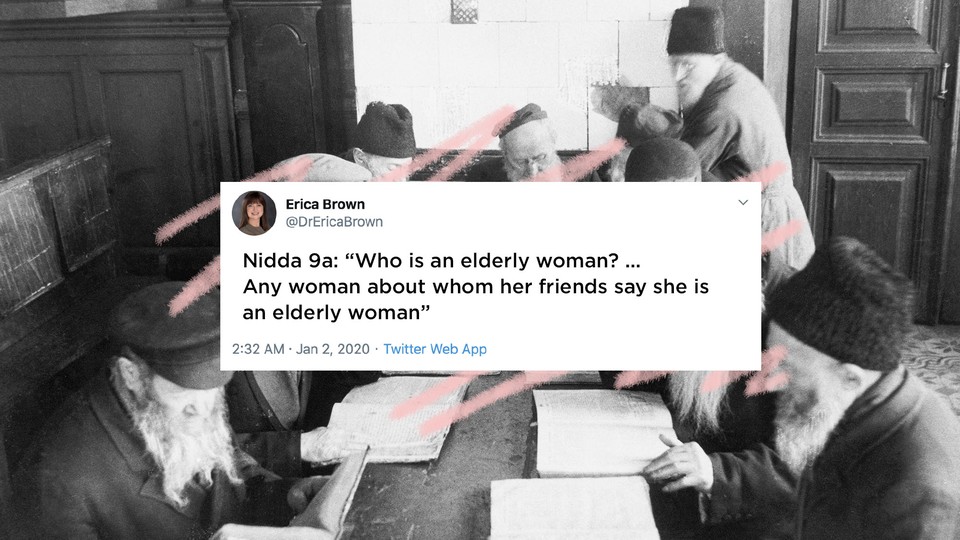

As part of my Daf Yomi project, every morning I tweet an insight from the daily Talmud page and then a corresponding relevant quote I’ve found online, amusing myself with the juxtaposition of old and new. On Nidda, page 9a, I tweeted this from Rabbi Judah, “Who is an elderly woman? … Any woman about whom her friends say she is an elderly woman,” next to Arthur Baer’s keen observation about women at a party: “The ladies looked one another over with microscopic carelessness.” On Keritot 12a, I tweeted “A person is deemed more credible about himself than 100 people” beside Ann Landers’s astute advice: “Know yourself. Don’t accept your dog’s admiration as conclusive evidence that you are wonderful.”

Talmudic scholarly insults are also great to tweet, such as this one from Bekhorot 58a, starring my champion: “Ben Azzai says, ‘All the sages of Israel appear to me as garlic peel, except this bald one.’” Arrogance and humility live side by side in the Talmud, so when a scholar issued a retraction or caught his own errors, I almost always tweeted it. It was, however, more fun when scholars caught one another’s mistakes or mishaps, such as when Rav Sheshet said of a colleague, “He must have been falling asleep when he said this.”

When I first started, distilling a complex, ancient Babylonian legal debate into 140 characters seemed ridiculous. But then Twitter became a vehicle for determining foreign policy and waging political and culture wars. The Talmud looks almost simple in comparison. And while I was tweeting, others were learning and producing daily haikus, limericks, and artwork on the daily page. One woman wrote a stunning personal memoir of studying Daf Yomi. Others wrote thematic literary essays or blogged about science and medicine on the Talmud’s pages. These timeworn and sometimes tedious texts were being reinterpreted and explained in fresh, creative ways by unexpected students.

Now, only a few days from completing the Daf Yomi cycle, I am nearing my last tweet. Through this modern medium, I conveyed the Talmud, but I also betrayed it. The rabbis made a distinction between chaye sha’a (matters of the moment) and chaye olam (matters of eternity). Tweeting on a Talmud page helped me use the ephemerality of social media—its sewer of partisan politics and trending videos—to touch a little piece of that eternity each morning. But often, unable to reduce a complicated argument into Twitter’s narrow confines, I bypassed content for a throwaway line. Because I could rarely encapsulate a legal debate in so few characters, I often tweeted something tangential from the page. My spindle has spun 4,779 threads but very little wisdom.

I’m in Jerusalem as I write this, rising to study the last of my pages to the sounds of the muezzin calling Muslims to prayer. I am here to stop tweeting and to mark this occasion with tens of thousands of others who, in halls, synagogues, and major sports arenas around the world, will celebrate the Talmud’s completion with a siyyum—a ritual closure. We will study an excerpt from the last page of the Talmud. We will pray to be renewed by our learning and to renew it. We will study the first page of the Talmud again, as the circle of literacy begins anew. And for the first time in the Talmud’s long history, this year thousands of women will be participating together in a siyyum in the largest convention center in the Middle East—not merely as supporters of their sons and husbands, but as scholars themselves. I will read the Talmud’s last words with other women who made this long commitment to its ancient wisdom. True to Rabbi Hyrcanus’s words, the room will be on fire.